Animal Traffic: Making, Remaking, and Unmaking Commodities in Global Live Wildlife Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Front Page First Opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, It Was Instantly Heralded As a Classic

SUPPORT FOR THE 2019 SEASON OF THE FESTIVAL THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY DANIEL BERNSTEIN AND CLAIRE FOERSTER PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP 2 DIRECTOR’S NOTES SCAVENGING FOR THE TRUTH BY GRAHAM ABBEY “Were it left to me to decide between a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1787 When The Front Page first opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, it was instantly heralded as a classic. Nearly a century later, this iconic play has retained its place as one of the great American stage comedies of all time. Its lasting legacy stands as a testament to its unique DNA: part farce, part melodrama, with a healthy dose of romance thrown into the mix, The Front Page is at once a veneration and a reproof of the gritty, seductive world of Chicago journalism, firmly embedded in the freewheeling euphoria of the Roaring Twenties. According to playwrights (and former Chicago reporters) Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, the play allegedly found its genesis in two real-life events: a practical joke carried out on MacArthur as he was heading west on a train with his fiancée, and the escape and disappearance of the notorious gangster “Terrible” Tommy consuming the conflicted heart of a city O’Conner four days before his scheduled caught in the momentum of progress while execution at the Cook County Jail. celebrating the underdogs who were lost in its wake. O’Conner’s escape proved to be a seminal moment in the history of a city struggling Chicago’s metamorphosis through the to find its identity amidst the social, cultural “twisted twenties” is a paradox in and of and industrial renaissance of the 1920s. -

First Photographic and Genetic Records of the Genus Martella (Araneae: Salticidae) Ryan Kaldari 1

Peckhamia 116.1 Photographic and genetic records of Martella 1 PECKHAMIA 116.1, 11 October 2014, 1―7 ISSN 2161―8526 (print) urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C56F4D2F-64EB-419F-ACEC-B79B3CE0B5C0 (registered 10 OCT 2014) ISSN 1944―8120 (online) First photographic and genetic records of the genus Martella (Araneae: Salticidae) Ryan Kaldari 1 1 644 9th St. Apt. A, Oakland, California 94607, USA, email [email protected] ABSTRACT: Phylogenetic analysis of the 28S gene supports a close relationship between Martella Peckham & Peckham 1892, Sarinda Peckham & Peckham 1892, and Zuniga Peckham & Peckham 1892 within the Amycoida clade. The genus is recorded from Belize for the first time, with photographs of a single male specimen of a possibly undescribed species. KEY WORDS: Martella, jumping spider, Salticidae, Amycoida, phylogeny This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author is credited. Introduction Martella Peckham & Peckham 1892 is a genus of ant-like spiders in the family Salticidae, native to North and South America, with a range spanning from Mexico to northern Argentina. The genus is poorly known and currently consists of twelve recognized species, six of which are described only from a single sex (World Spider Catalog 2014). It was synonymized with Sarinda Peckham & Peckham 1892 by Simon in 1901, restored by Galiano in 1964, and most recently revised by Galiano in 1996. In this paper, the first photographic and genetic records for the genus are presented, as well as a limited analysis of its relationship to other genera in the Amycoida clade. -

Animal Imagery in Toni Morrison: Degradation and Community

Cusanelli 1 Olivia Cusanelli ENG 390 Dr. Boudreau 29 April 2016 Animal Imagery in Toni Morrison: Degradation and Community Toni Morrison’s novels Song of Solomon and Beloved are rich with imagery of nature that often connects with the characters. Something which is not always a prevalent aspect of the nature Morrison describes but is inherently present throughout the texts is the detailed descriptions and portrayal of animals. There are some explicit connections between animals and characters, most significantly between birds and Milkman and Paul D and numerous animals such as cows, beasts, and a rooster. What is so unique about the animals connected with the two central male characters of Song of Solomon and Beloved is the underlying symbolism associated with man and animal. Throughout both novels Milkman and Paul D are on very different paths of the African American male. Milkman, brought up in comfortable middle-class wealth has not been subjected to hardship because of his race unlike many of his peers. Paul D on the other hand, has struggled immensely during his life as a slave. The novels are set in two different time periods, Song of Solomon during 1931-1963 in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Virginia and Beloved in 1873 Cincinnati, Ohio with flashbacks as far back as 1850. These two vastly different experiences as African American men are possibly a representation of the progression of the social roles of the African American male. In her novel Beloved Toni Morrison uses animals to portray the degradation of African American men through Paul D who struggles to obtain an ideal sense of manhood, and in Song of Solomon Morrison uses animals to show that in order to survive in this country as a black male, one must share the struggle through community. -

A Protocol for Online Documentation of Spider Biodiversity Inventories Applied to a Mexican Tropical Wet Forest (Araneae, Araneomorphae)

Zootaxa 4722 (3): 241–269 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4722.3.2 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:6AC6E70B-6E6A-4D46-9C8A-2260B929E471 A protocol for online documentation of spider biodiversity inventories applied to a Mexican tropical wet forest (Araneae, Araneomorphae) FERNANDO ÁLVAREZ-PADILLA1, 2, M. ANTONIO GALÁN-SÁNCHEZ1 & F. JAVIER SALGUEIRO- SEPÚLVEDA1 1Laboratorio de Aracnología, Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Biología Comparada, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Circuito Exterior s/n, Colonia Copilco el Bajo. C. P. 04510. Del. Coyoacán, Ciudad de México, México. E-mail: [email protected] 2Corresponding author Abstract Spider community inventories have relatively well-established standardized collecting protocols. Such protocols set rules for the orderly acquisition of samples to estimate community parameters and to establish comparisons between areas. These methods have been tested worldwide, providing useful data for inventory planning and optimal sampling allocation efforts. The taxonomic counterpart of biodiversity inventories has received considerably less attention. Species lists and their relative abundances are the only link between the community parameters resulting from a biotic inventory and the biology of the species that live there. However, this connection is lost or speculative at best for species only partially identified (e. g., to genus but not to species). This link is particularly important for diverse tropical regions were many taxa are undescribed or little known such as spiders. One approach to this problem has been the development of biodiversity inventory websites that document the morphology of the species with digital images organized as standard views. -

A Summary List of Fossil Spiders

A summary list of fossil spiders compiled by Jason A. Dunlop (Berlin), David Penney (Manchester) & Denise Jekel (Berlin) Suggested citation: Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2010. A summary list of fossil spiders. In Platnick, N. I. (ed.) The world spider catalog, version 10.5. American Museum of Natural History, online at http://research.amnh.org/entomology/spiders/catalog/index.html Last udated: 10.12.2009 INTRODUCTION Fossil spiders have not been fully cataloged since Bonnet’s Bibliographia Araneorum and are not included in the current Catalog. Since Bonnet’s time there has been considerable progress in our understanding of the spider fossil record and numerous new taxa have been described. As part of a larger project to catalog the diversity of fossil arachnids and their relatives, our aim here is to offer a summary list of the known fossil spiders in their current systematic position; as a first step towards the eventual goal of combining fossil and Recent data within a single arachnological resource. To integrate our data as smoothly as possible with standards used for living spiders, our list follows the names and sequence of families adopted in the Catalog. For this reason some of the family groupings proposed in Wunderlich’s (2004, 2008) monographs of amber and copal spiders are not reflected here, and we encourage the reader to consult these studies for details and alternative opinions. Extinct families have been inserted in the position which we hope best reflects their probable affinities. Genus and species names were compiled from established lists and cross-referenced against the primary literature. -

The White Animals

The 5outh 'r Greatert Party Band Playr Again: Narhville 'r Legendary White AniMalr Reunite to 5old-0ut Crowdr By Elaine McArdle t's 10 p.m. on a sweltering summer n. ight in Nashville and standing room only at the renowned Exit/In bar, where the crowd - a bizarre mix of mid Idle-aged frat rats and former punk rockers - is in a frenzy. Some drove a day or more to get here, from Florida or Arizona or North Carolina. Others flew in from New York or California, even the Virgin Islands. One group of fans chartered a jet from Mobile, Ala. With scores of people turned away at the door, the 500 people crushed into the club begin shouting song titles before the music even starts. "The White Animals are baaaaaaack!" bellows one wild-eyed thirty something, who appears mainstream in his khaki shorts and docksiders - until you notice he reeks of patchouli oil and is dripping in silver-and-purple mardi gras beads, the ornament of choice for White Animals fans. Next to him, a mortgage banker named Scott Brown says he saw the White Animals play at least 20 times when he was an undergrad at the University of Tennessee. He wouldn't have missed this long-overdue reunion - he saw both the Friday and Saturday shows - for a residential closing on Mar-A-Lago. Lead singer Kevin Gray, a one-time medical student who dropped his stud ies in 1978 to work in the band fulltime, steps onto the stage and peers out into the audience, recognizing faces he hasn't seen in more than a decade. -

If the Stones Were the Bohemian Bad Boys of the British R&B Scene, The

anEHEl s If the Stones were the bohemian bad boys of the British R&B scene, the Animals were its working-class heroes. rom the somber opening chords of the than many of his English R&B contemporaries. The Animals’ first big hit “House of the Rising Animals’ best records had such great resonance because Sun,” the world could tell that this band Burdon drew not only on his enthusiasm, respect and was up to something different than their empathy for the blues and the people who created it, but British Invasion peers. When the record also on his own English working class sensibilities. hitP #1 in England and America in the summer and fall of If the Stones were the decadent, bohemian bad boys 1964, the Beatles and their Mersey-beat fellow travellers of the British R&B scene, the Animals were its working- dominated the charts with songs like “I Want to Hold Your class heroes. “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” and “It’s My Hand” and “Glad All Over.” “House of the Rising Sun,” a tra Life,” two Brill Building-penned hits for the band, were ditional folk song then recently recorded by Bob Dylan on informed as much by working-class anger as by Burdons his debut album, was a tale of the hard life of prostitution, blues influences, and the bands anthemic background poverty and despair in New Orleans. In the Animals’ vocals underscored the point. recording it became a full-scale rock & roll drama, During the two-year period that the original scored by keyboardist Alan Price’s rumbling organ play Animals recorded together, their electrified reworkings of ing and narrated by Eric Burdons vocals, which, as on folk songs undoubtedly influenced the rise of folk-rock, many of the Animals’ best records, built from a foreboding and Burdons gritty vocals inspired a crop of British and bluesy lament to a frenetic howl of pain and protest. -

Araneae: Salticidae: Sarindini)

Caracteres morfológicos y comportamentales de la mirmecomorfia en Sarinda marcosi Piza, 1937 (Araneae: Salticidae: Sarindini) Tesina de grado de la Licenciatura en Ciencias Biológicas Profundización en Entomología Damián Martín Hagopián Chenlo TUTOR Miguel Simó CO-TUTORA Anita Aisenberg Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República Marzo 2019 1 CONTENIDOS AGRADECIMIENTOS……….……………………………………………………….3 RESUMEN……………………………………………………………………………….4 INTRODUCCIÓN………………………………………………………………………5 MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS……………………………………………..…..……6 Determinación taxonómica y distribución……………………………6 Índice de mirmecomorfia…………….……..……...……………………...7 Descripción de la mirmecomorfia………………………………………..7 Análisis estadísticos…………………………………………………………….9 RESULTADOS……………………………………………………….…………..…..10 Taxonomía……………………………………………….………………..……..10 Material examinado……………………..................................…..10 Historia natural………………………………………………………………….13 Distribución en el país…………………………………………..…………..15 Convergencias morfológicas y de coloración..……...……………15 Convergencias comportamentales………………………..…………..19 Ataques……………………..…………………………..…………………………23 DISCUSIÓN…………………………………………………………………………….23 BIBLIOGRAFÍA……………………………………………………………………….27 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS Especialmente a mis tutores Anita Aisenberg y Miguel Simó por orientarme en esta investigación y por todo lo que me han enseñado, disfrutando los caminos recorridos, felices de compartir con generosidad y humildad sus saberes. A Álvaro Laborda, por su compañerismo incondicional, enseñándome un sinfín de cuestiones teóricas y prácticas -

Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly - Not Even Past

Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 19 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly by Nathan Stone Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Confederacy” I started going to camp in 1968. We were still just children, but we already had Vietnam to think about. The evening news was a body count. At camp, we didn’t see the news, but we listened to Eric Burdon and the Animals’ Sky Pilot while doing our beadwork with Father Pekarski. Pekarski looked like Grandpa from The Munsters. He was bald with a scowl and a growl, wearing shorts and an official camp tee shirt over his pot belly. The local legend was that at night, before going out to do his vampire thing, he would come in and mix up your beads so that the red ones were in the blue box, and the black ones were in the white box. Then, he would twist the thread on your bead loom a hundred and twenty times so that it would be impossible to work with the next day. And laugh. In fact, he was as nice a May 06, 2020 guy as you could ever want to know. More from The Public Historian BOOKS America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019) April 20, 2020 More Books The Munsters Back then, bead-craft might have seemed like a sort of “feminine” thing to be doing at a boys’ camp. -

Download Download

Behavioral Ecology Symposium ’96: Cushing 165 MYRMECOMORPHY AND MYRMECOPHILY IN SPIDERS: A REVIEW PAULA E. CUSHING The College of Wooster Biology Department 931 College Street Wooster, Ohio 44691 ABSTRACT Myrmecomorphs are arthropods that have evolved a morphological resemblance to ants. Myrmecophiles are arthropods that live in or near ant nests and are considered true symbionts. The literature and natural history information about spider myrme- comorphs and myrmecophiles are reviewed. Myrmecomorphy in spiders is generally considered a type of Batesian mimicry in which spiders are gaining protection from predators through their resemblance to aggressive or unpalatable ants. Selection pressure from spider predators and eggsac parasites may trigger greater integration into ant colonies among myrmecophilic spiders. Key Words: Araneae, symbiont, ant-mimicry, ant-associates RESUMEN Los mirmecomorfos son artrópodos que han evolucionado desarrollando una seme- janza morfológica a las hormigas. Los Myrmecófilos son artrópodos que viven dentro o cerca de nidos de hormigas y se consideran verdaderos simbiontes. Ha sido evaluado la literatura e información de historia natural acerca de las arañas mirmecomorfas y mirmecófilas . El myrmecomorfismo en las arañas es generalmente considerado un tipo de mimetismo Batesiano en el cual las arañas están protegiéndose de sus depre- dadores a través de su semejanza con hormigas agresivas o no apetecibles. La presión de selección de los depredadores de arañas y de parásitos de su saco ovopositor pueden inducir una mayor integración de las arañas mirmecófílas hacia las colonias de hor- migas. Myrmecomorphs and myrmecophiles are arthropods that have evolved some level of association with ants. Myrmecomorphs were originally referred to as myrmecoids by Donisthorpe (1927) and are defined as arthropods that mimic ants morphologically and/or behaviorally. -

Downloads, and Weekly Attendees

riscilla apersVol 32, No 4 | Autumn 2018 PPThe academic journal of CBE International Social Sciences 3 Muted Group Theory: A Tool for Hearing Marginalized Voices Linda Lee Smith Barkman 8 The Importance of Age Norms When Considering Gender Issues Jason Eden and Naomi Eden 14 Christian Women’s Beliefs on Female Subordination and Male Authority Susan H. Howell and Kristyn Duncan 15 The Experiences of Women in Church and Denominational Leadership Susan H. Howell and Ariel Thompson 18 Marriage Ideology and Decision-Making Susan H. Howell, Bethany G. Lester, Alayna N. Owens 23 The Delight of Daughters: A Theology of Daughterhood Beulah Wood 29 Book Review: Biblical Porn: Affect, Labor, and Pastor Mark Driscoll’s Evangelical Empire by Jessica Johnson Jamin Hübner Priscilla and Aquila instructed Apollos more perfectly in the way of the Lord. (Acts 18:26) I Tertius . that made you fight to stay awake. It was the art (or lack thereof) of communication, which is a social science. Psychology and sociology, ethnography Consider counseling, a profession and skill set which and ethnology, political science and arises primarily from psychology. A Christian counselor economics. These and other social will approach psychology, and therefore counseling, with sciences are tools for understanding a certain set of theological beliefs. To give a final example, the people of the world—as individuals, Bible translation—surely an endeavor that underlies almost as families, as groups, as cultures and all biblical interpretation—happens at the intersection of subcultures. The articles in this issue of biblical studies and human language. And, of course, the Priscilla Papers all arise, directly or indirectly, from one or study of language (linguistics) and of the cultures that more social sciences. -

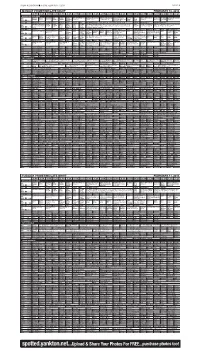

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos for FREE...Purchase

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 2014 PAGE 9B MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT FEBRUARY 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Curious Arthur Å WordGirl Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Independent Lens The Red BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS George (DVS) Å (DVS) Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Detroit” (N) Å “Eugene, OR” Å Mississippi agency and Green World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Detroit” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report civil rights. (N) Show News Å KTIV $ 4 $ XXII Olympics Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. Å News 4 XXII Olympics XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. From Sochi, KDLT XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle NBC Speed Skating, Biath- Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Russia. Alpine skiing: women’s super combined; freestyle skiing; short track. (N News Å Short Track, Luge. Å Skiing, Short Track. (In Stereo) Å KDLT % 5 % lon. Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory Same-day Tape) (In Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. Phil Å The Dr. Oz Show News at ABC News Inside The Bachelor (N) (In Stereo) Å Castle “Valkyrie” News Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline Paid Inside ABC World News Dr.