A Study on Taiwan's Food Dollar Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modeling Incipient Use of Neolithic Cultigens by Taiwanese Foragers: Perspectives from Niche Variation Theory, the Prey Choice Model, and the Ideal Free Distribution

quaternary Article Modeling Incipient Use of Neolithic Cultigens by Taiwanese Foragers: Perspectives from Niche Variation Theory, the Prey Choice Model, and the Ideal Free Distribution Pei-Lin Yu Department of Anthropology, Boise State University, 1910 University Dr., Boise, ID 83725, USA; [email protected] Received: 3 June 2020; Accepted: 14 August 2020; Published: 7 September 2020 Abstract: The earliest evidence for agriculture in Taiwan dates to about 6000 years BP and indicates that farmer-gardeners from Southeast China migrated across the Taiwan Strait. However, little is known about the adaptive interactions between Taiwanese foragers and Neolithic Chinese farmers during the transition. This paper considers theoretical expectations from human behavioral ecology based models and macroecological patterning from Binford’s hunter-gatherer database to scope the range of responses of native populations to invasive dispersal. Niche variation theory and invasion theory predict that the foraging niche breadths will narrow for native populations and morphologically similar dispersing populations. The encounter contingent prey choice model indicates that groups under resource depression from depleted high-ranked resources will increasingly take low-ranked resources upon encounter. The ideal free distribution with Allee effects categorizes settlement into highly ranked habitats selected on the basis of encounter rates with preferred prey, with niche construction potentially contributing to an upswing in some highly ranked prey species. In coastal plain habitats preferred by farming immigrants, interactions and competition either reduced encounter rates with high ranked prey or were offset by benefits to habitat from the creation of a mosaic of succession ecozones by cultivation. Aquatic-focused foragers were eventually constrained to broaden subsistence by increasing the harvest of low ranked resources, then mobility-compatible Neolithic cultigens were added as a niche-broadening tactic. -

ACROSS the TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017

VOLUME 4 2013–2014 ACROSS THE TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017 Compendium of works from the China Leadership Monitor ALAN D. ROMBERG ACROSS THE TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017 Compendium of works from the China Leadership Monitor ALAN D. ROMBERG VOLUME FOUR January 14 2013–March 14, 2014 JUNE 2018 Stimson cannot be held responsible for the content of any webpages belonging to other firms, organizations, or individuals that are referenced by hyperlinks. Such links are included in good faith to provide the user with additional information of potential interest. Stimson has no influence over their content, their correctness, their programming, or how frequently they are updated by their owners. Some hyperlinks might eventually become defunct. Copyright © 2018 Stimson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from Stimson. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1211 Connecticut Avenue Northwest, 8th floor Washington, DC 20036 Telephone: 202.223.5956 www.stimson.org Preface Brian Finlay and Ellen Laipson It is our privilege to present this collection of Alan Romberg’s analytical work on the cross-Strait relationship between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. Alan joined Stimson in 2000 to lead the East Asia Program after a long and prestigious career in the Department of State, during which he was an instrumental player in the development of the United States’ policy in Asia, particularly relating to the PRC and Taiwan. He brought his expertise to bear on his work at Stimson, where he wrote the seminal book on U.S. -

White Paper 2007--1

January 17, 2007 Approved by the 3,024th Meeting of the Executive Yuan White Paper on Science and Technology (2007–2010) Innovative Capabilities and Citizens’ Quality of Life will Reach the Level of a Developed Nation by 2015 National Science Council Republic of China Table of Contents Abstract........................................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 – Foreword.................................................................................................................1 Chapter 2 – Current State of Science and Technology in Taiwan............................................5 2.1 S&T Development Framework and Policymaking Mechanism .................................5 2.2 Resources and Outputs of Scientific and Technological Development ......................7 I. Expenditure.......................................................................................................................7 II. Workforce......................................................................................................................12 III. Output ..........................................................................................................................16 2.3 Major Scientific and Technological Activities............................................................22 I. Strategic High-Tech Living Industries (Industry Technology Strategy Review Board Meeting, BioTaiwan Committee Meeting) ................................................................................22 -

IPSI Case Study Summary Sheet

IPSI Case Study Summary Sheet Please fill out the sheet below to summarize your case study, but maintain the summary to 2 pages only. Texts in gray explain the description of each box and please delete these when you fill out. Basic Information Title of case study (should be concise and within approximately 20 words) Strengthening Taiwan Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (TPSI), 2018-2020: think global, adapt national, act local Submitting IPSI member organization(s) Forestry Bureau, Council of Agriculture, Chinese Taipei National Dong Hwa University (NDHU), Chinese Taipei Other contributing organization(s) (IPSI members and/or non-members) None Author(s), affiliation(s) and profile(s) (please include a profile of around 50 words for each author and contact information) 1) Forestry Bureau, Council of Agriculture, Chinese Taipei: Dr. Hwa-Ching Lin, Director General Ms. Yu-Chuan Lo, Director of Conservation Division Dr. Chih-Chin Shih, Chief of Habitat Management Section, Conservation Division, the contact person Ms. Ya-Ling Chang, Staff of Habitat Management Section, Conservation Division, 2) National Dong Hwa University (NDHU), Chinese Taipei: Ms. Paulina G. Karimova, PhD Student, NDHU, Specialist Degree in International Relations (Asia Studies), MSc Degree in Environmental Science Ms. Ya-Hsin Chiu, Research Assistant, NDHU, Joint Bachelor and MSc Degree in Environmental Education and Eco-tourism *Dr. Kuang-Chung Lee, Associate Professor, NDHU, Chinese Taipei; *corresponding author. In 1989, graduated from the Geography Department, National Taiwan University; from 1991 to 1997, worked for the Council of Agriculture and Taroko National Park, Taiwan; in 2001, got Ph.D. degree in the Geography Department, University College London; currently is an Associate Professor at National Dong Hwa University (NDHU), Taiwan, a commission member of IUCN/WCPA, ICOMOS. -

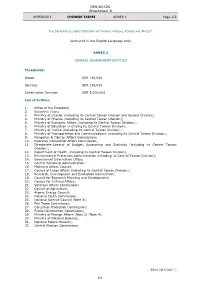

GPA/W/326 Attachment K K1

GPA/W/326 Attachment K APPENDIX I CHINESE TAIPEI ANNEX 1 Page 1/2 THE SEPARATE CUSTOMS TERRITORY OF TAIWAN, PENGHU, KINMEN AND MATSU* (Authentic in the English Language only) ANNEX 1 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT ENTITIES Thresholds: Goods SDR 130,000 Services SDR 130,000 Construction Services SDR 5,000,000 List of Entities: 1. Office of the President; 2. Executive Yuan; 3. Ministry of Interior (including its Central Taiwan Division and Second Division); 4. Ministry of Finance (including its Central Taiwan Division); 5. Ministry of Economic Affairs (including its Central Taiwan Division); 6. Ministry of Education (including its Central Taiwan Division); 7. Ministry of Justice (including its Central Taiwan Division); 8. Ministry of Transportation and Communications (including its Central Taiwan Division); 9. Mongolian & Tibetan Affairs Commission; 10. Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission; 11. Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (including its Central Taiwan Division); 12. Department of Health (including its Central Taiwan Division); 13. Environmental Protection Administration (including its Central Taiwan Division); 14. Government Information Office; 15. Central Personnel Administration; 16. Mainland Affairs Council; 17. Council of Labor Affairs (including its Central Taiwan Division); 18. Research, Development and Evaluation Commission; 19. Council for Economic Planning and Development; 20. Council for Cultural Affairs; 21. Veterans Affairs Commission; 22. Council of Agriculture; 23. Atomic Energy Council; 24. National Youth Commission; 25. National Science Council (Note 3); 26. Fair Trade Commission; 27. Consumer Protection Commission; 28. Public Construction Commission; 29. Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Note 2) (Note 4); 30. Ministry of National Defense; 31. National Palace Museum; 32. Central Election Commission. … 2014 (WT/Let/…) K1 GPA/W/326 Attachment K APPENDIX I CHINESE TAIPEI ANNEX 1 Page 2/2 * In English only. -

Application Forms】

Index General Information of TAIWAN INNOTECH EXPO 2021 (TIE2021) .......................... 1 1. Objectives ......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Organizers ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 3. Exhibitor's Timetable for TIE 2021 ..................................................................................................................... 2 4. Venue .................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 5. Exhibiting Area ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 6. Scheduled Promotion Events ................................................................................................................................. 4 7. Publicity Campaign ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 8. Booth Rental .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 9. Payment Schedule ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Looking Southward 向南看 TAIWAN BUSINESS TOPICS February 2019 | Vol

February 2019 | Vol. 49 | Issue 2 THE AMERICAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE IN TAIPEI IN OF COMMERCE THE AMERICAN CHAMBER Looking Southward 向南看 TAIWAN BUSINESS TOPICS TAIWAN February 2019 | Vol. 49 | Issue 2 Vol. 2019 | February 中 華 郵 政 北 台 字 第 SPECIAL REPORT 2019 BUSINESS CLIMATE SURVEY INDUSTRY FOCUS 5000 號 執 照 登 記 為 雜 誌TECHNOLOGY 交 寄 ISSUE SPONSOR Published by the American Chamber Of NT$150 Commerce In Taipei Read TOPICS Online at topics.amcham.com.tw 2_2019_Cover2.indd 1 2019/2/6 下午10:11 CONTENTS NEWS AND VIEWS 4 Editorial In a Tough Year, Focus on Reform and Innovation FEBRUARY 2019 VOLUME 48, NUMBER 2 6 President’s View Staying Positive in 2019 Publisher By William Foreman William Foreman Editor-in-Chief 7 Taiwan Briefs Don Shapiro By Don Shapiro Art Director/ / Production Coordinator Katia Chen Manager, Publications Sales & Marketing Caroline Lee COVER SECTION Translation Kevin Chen, Yichun Chen, Charlize Hung, Looking Southward Andrew Wang 向南看 By Don Shapiro 撰文/沙蕩 12 The New Southbound Policy American Chamber of Commerce in Taipei 129 MinSheng East Road, Section 3, in a New Context 7F, Suite 706, Taipei 10596, Taiwan P.O. Box 17-277, Taipei, 10419 Taiwan 南向 Tel: 2718-8226 Fax: 2718-8182 e-mail: [email protected] The New Southbound Policy, website: http://www.amcham.com.tw launched in 2016 to enhance Taiwan’s contacts with countries 050 2718-8226 2718-8182 in the surrounding region, Taiwan Business Topics is a publication of the American has recently taken on added Chamber of Commerce in Taipei, ROC. -

Terry Yu-Hsien Yu

Terry Yu-Hsien Yu B.S., Agricultural Economics, Taiwan Provincial College of Agriculture, 1957 M.S., Agricultural Economics, National Chung Hsing University, 1961 Ph.D., Agricultural Economics, Purdue University, 1967 Post-graduate studies, Oregon State University, 1962 Dr. Yu served as chairman of the Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan, in the Government of Taiwan from 1988 to 1992. As chairman, he was effectively the Minister of Agriculture of Tai-wan. Since stepping down from the chairmanship in 1992 for health reasons, Dr. Yu has served as an advisor to the Council of Agriculture. Prior to holding the office of chairman, he was the Commissioner of Agriculture and Forestry of the Taiwan Provin-cial government. In the early days of his career, Dr. Yu was progressively an associate professor, professor, and then Chairman of the Department of Agricultural Economics at the National Chung Hsing University. In 1972 Dr. Yu became a senior specialist with the Chinese- American Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction. He was appointed senior specialist of the Planning and Programming Division following the Commission's reorganization into the Council for Agricultural Planning and Development, a cabinet advisory agency. Five months later, Dr. Yu accepted the post as president of the National Chiayi Junior College of Agriculture. As Commissioner of Agriculture and Forestry in the Taiwan provincial government, he was cited dozens of times by the government for his meritorious service. Dr. Yu was elected a member of the Kuomintang Central Committee at the 13th congress and was then, shortly after, appointed the chairman of the Council of Agriculture, the highest policy-making body for agricultural affairs. -

The Case of Taiwan's Financial System

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Deregulation and Interdependence in the Asia-Pacific Region, NBER-EASE Volume 8 Volume Author/Editor: Takatoshi Ito and Anne O. Krueger, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-38674-0 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/ito_00-1 Conference Date: June 19-21, 1997 Publication Date: January 2000 Chapter Title: The Reform of the Business Service Sector: The Case of Taiwan’s Financial System Chapter Author: Ching-hsi Chang Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8482 Chapter pages in book: (p. 227 - 254) The Reform of the Business Service Sector The Case of Taiwan’s Financial System Ching-hsi Chang Reform of financial services has been one of the major development de- vices used in Asian newly industrializing countries (NICs) in the 1990s. Although the service sector has been recognized as a key to growth by many great economists, the sector is viewed with hostility by intellectuals and society in general. In Taiwan, the sector has long been discriminated against by industrial policy. The reform of the Taiwanese business service sector is treated as a key stimulus to the country’s further economic devel- opment, but there are some structural dilemmas in the reform program. Using the financial system as an example, this paper illuminates the re- form policies and the recent problems of the business service sector in Taiwan. Section 7.1 will briefly depict the significance of and the hostility to the business service sector. -

IPSI Case Study Summary Sheet Basic Information Title of Case Study

IPSI Case Study Summary Sheet Basic Information Title of case study Promoting Under-Forest Economy under the concept of Satoyama Initiative: A Case Study of Wutai Township, Pingtung County, Chinese Taipei Submitting IPSI National Pingtung University of Science and Technology (NPUST) member organization IPSI members: Forestry Bureau, Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan, Chinese Taipei Other contributing Non-members: Ministry of Education, Chinese Taipei organization National Dong-Hwa University (NDHU), Chinese Taipei Taiwan Forestry Research Institute, Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan, Chinese Taipei Authors and Dr. Meihui Chen, Professor, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, affiliations Chinese Taipei, corresponding author Format of case study Manuscript Language English Keywords Community forestry, Under-Forest Economy, Ecotourism, Collaborative management Date of submission 31 Dec 2018 Web link http://mportal.npust.edu.tw/bin/home.php?Lang=en Geographical Information Country Chinese Taipei Location Wutai Township, Pingtung County, Chinese Taipei Longitude/latitude or Google Maps link https://goo.gl/maps/H5nbSmTkGmP2 Ecosystem(s) Forest x Grassland Agricultural x In-land water Coastal Dryland Mountain x Urban/peri-urban Other Socioeconomic and environmental characteristics of the area Wutai Township (Vedai in the Rukai language) has a total area of roughly 280 square kilometers, with an average elevation of more than 1,000 meters, and the forest coverage is nearly 98%. There is no railway or highway system cutting in the territory, and there is no large-scale development and construction, thus maintaining the most complete traditional aboriginal areas. According to official statistics from 2018, the population of Wutai Township is about 3,400. The main ethnic group is the Taiwanese aborigines, the Rukai, accounting for 99%. -

Market Guide for Bc Agrifood and Seafood Exporters Taiwan

B.C. MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE MARKET GUIDE FOR B.C. AGRIFOOD AND SEAFOOD EXPORTERS TAIWAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Section 2: Introduction to the Taiwanese Market .................................................................................... 1 2.1 – TAIWAN’S ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT ......................................................................................................... 1 2.2 – TAIWAN’S AGRIFOOD AND SEAFOOD SECTOR .......................................................................................... 1 2.3 – TAIWAN’S AGRIFOOD AND SEAFOOD IMPORTS ....................................................................................... 1 2.4 – CULINARY CULTURE, CONSUMER LIFESTYLE AND CONSUMER EXPECTATIONS ...................... 3 2.5 – MARKET INTELLIGENCE ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Section 3: Market Readiness ............................................................................................................................. 6 3.1 – GOVERNMENT OF TAIWAN AGENCIES INVOLVED IN OVERSEEING IMPORTS ........................... 6 3.2 – REQUIREMENTS, STANDARDS & REGULATIONS ...................................................................................... 7 Section 4: Selling to Taiwan ............................................................................................................................. -

SA-TAIWAN Enews OCTOBER 25TH 2019 PUBLISHER: MATTHEW CHOU ISSUE 10

Taipei Liaison Office in the RSA SA-TAIWAN eNews OCTOBER 25TH 2019 PUBLISHER: MATTHEW CHOU ISSUE 10 I, and the South African Government, have enormous appreciation for the contribution that the Government of the Republic of China (Taiwan) has made to the commitment of the Govern- ment sector in the economic development in Africa. The ROC (Taiwan) further, made a gener- ous and much appreciated contribution to South Africa's transition to democracy . Statement by President Nelson Mandela—27 November 1996 Tsai Praises Taiwan’s Human Rights Progress at 40th FIDH Congress President Tsai Ing-wen said that the into local laws so as to further en- government is leaving no stone un- trench associated core concepts into turned in promoting human rights the fabric of society. and making Taiwan a more fair and just country. Tsai said the government will not budge an inch in ensuring human Safeguarding human rights remains a rights progress remains on the fast top priority for the government, Tsai track, and has set up a unique volun- said. Real progress has been achieved tary assessment process involving in removing job restrictions and President Tsai Ing-wen delivers her academics from around the globe eliminating discrimination against conducting reviews and communicat- opening address at the 40th FIDH women in the workplace, as well as ing with civic groups and government initiating judicial reform to create a Congress in Taipei City. (Courtesy of agencies. legal system better reflecting the Presidential Office) wishes of the people, she added. Taiwan’s nongovernmental organisa- tions also play a central role in this Tsai made the remarks while opening outstanding venue for Taiwan to process, Tsai said, citing invaluable the 40th Congress of the Interna- share its democratic journey while contributions in assisting the govern- tional Federation for Human Rights learning from other countries’ experi- ment improve protection of the peo- (FIDH) in Taipei City—the first time ences.