Oskar KOLBERG Composer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guillaume Tell Guillaume

1 TEATRO MASSIMO TEATRO GIOACHINO ROSSINI GIOACHINO | GUILLAUME TELL GUILLAUME Gioachino Rossini GUILLAUME TELL Membro di seguici su: STAGIONE teatromassimo.it Piazza Verdi - 90138 Palermo OPERE E BALLETTI ISBN: 978-88-98389-66-7 euro 10,00 STAGIONE OPERE E BALLETTI SOCI FONDATORI PARTNER PRIVATI REGIONE SICILIANA ASSESSORATO AL TURISMO SPORT E SPETTACOLI ALBO DEI DONATORI FONDAZIONE ART BONUS TEATRO MASSIMO TASCA D’ALMERITA Francesco Giambrone Sovrintendente Oscar Pizzo Direttore artistico ANGELO MORETTINO SRL Gabriele Ferro Direttore musicale SAIS AUTOLINEE CONSIGLIO DI INDIRIZZO Leoluca Orlando (sindaco di Palermo) AGOSTINO RANDAZZO Presidente Leonardo Di Franco Vicepresidente DELL’OGLIO Daniele Ficola Francesco Giambrone Sovrintendente FILIPPONE ASSICURAZIONE Enrico Maccarone GIUSEPPE DI PASQUALE Anna Sica ALESSANDRA GIURINTANO DI MARCO COLLEGIO DEI REVISORI Maurizio Graffeo Presidente ISTITUTO CLINICO LOCOROTONDO Marco Piepoli Gianpiero Tulelli TURNI GUILLAUME TELL Opéra en quatre actes (opera in quattro atti) Libretto di Victor Joseph Etienne De Jouy e Hippolyte Louis Florent Bis Musica di Gioachino Rossini Prima rappresentazione Parigi, Théâtre de l’Academie Royale de Musique, 3 agosto 1829 Edizione critica della partitura edita dalla Fondazione Rossini di Pesaro in collaborazione con Casa Ricordi di Milano Data Turno Ora a cura di M. Elizabeth C. Bartlet Sabato 20 gennaio Anteprima Giovani 17.30 Martedì 23 gennaio Prime 19.30 In occasione dei 150 anni dalla morte di Gioachino Rossini Giovedì 25 gennaio B 18.30 Sabato 27 gennaio -

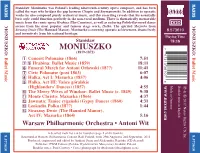

Moniuszko Was Poland’S Leading Nineteenth-Century Opera Composer, and Has Been Called the Man Who Bridges the Gap Between Chopin and Szymanowski

CMYK NAXOS NAXOS Stanisław Moniuszko was Poland’s leading nineteenth-century opera composer, and has been called the man who bridges the gap between Chopin and Szymanowski. In addition to operatic works he also composed purely orchestral music, and this recording reveals that his essentially lyric style could function perfectly in the non-vocal medium. There is thematically memorable music from the comic opera Hrabina (The Countess), as well as enduring Polish-flavoured dance DDD MONIUSZKO: scenes from his most popular and famous stage work, Halka. The spirited Mazurka from MONIUSZKO: Straszny Dwór (The Haunted Manor), Moniuszko’s crowning operatic achievement, draws freely 8.573610 and inventively from his national heritage. Playing Time Stanisław 78:18 MONIUSZKO 7 (1819-1872) 47313 36107 Ballet Music 1 Concert Polonaise (1866) 7:51 Ballet Music 2-5 Hrabina: Ballet Music (1859) 18:11 6 Funeral March for Antoni Orłowski (18??) 11:41 7 Civic Polonaise (post 1863) 6:07 8 Halka, Act I: Mazurka (1857) 4:06 9 Halka, Act III: Tańce góralskie 6 (Highlanders’ Dances) (1857) 4:55 www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ 0 The Merry Wives of Windsor: Ballet Music (c. 1849) 9:38 & Ꭿ ! Monte Christo: Mazurka (1866) 4:37 2017 Naxos Rights US, Inc. @ Jawnuta: Taniec cygański (Gypsy Dance) (1860) 4:31 # Leokadia Polka (18??) 1:44 $ Straszny Dwór (The Haunted Manor), Act IV: Mazurka (1864) 5:16 Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit A detailed track list can be found on page 2 of the booklet. 8.573610 8.573610 Recorded at Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall, Poland, from 29th August to 2nd September, 2011 Produced, engineered and edited by Andrzej Sasin and Aleksandra Nagórko (CD Accord) Publisher: PWM Edition (Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne), Kraków, Poland Booklet notes: Paul Conway • Cover photograph by dzalcman (iStockphoto.com). -

La Bohème Opera in Four Acts Music by Giacomo Puccini Italian Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica Afterscènes Da La Vie De Bohème by Henri Murger

____________________ The Indiana University Opera Theater presents as its 395th production La Bohème Opera in Four Acts Music by Giacomo Puccini Italian Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica AfterScènes da la vie de Bohème by Henri Murger David Effron,Conductor Tito Capobianco, Stage Director C. David Higgins, Set Designer Barry Steele, Lighting Designer Sondra Nottingham, Wig and Make-up Designer Vasiliki Tsuova, Chorus Master Lisa Yozviak, Children’s Chorus Master Christian Capocaccia, Italian Diction Coach Words for Music, Supertitle Provider Victor DeRenzi, Supertitle Translator _______________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Ninth Saturday Evening, November Tenth Friday Evening, November Sixteenth Saturday Evening, November Seventeenth Eight O’Clock Two Hundred Eighty-Fourth Program of the 2007-08 Season music.indiana.edu Cast (in order of appearance) The four Bohemians: Rodolfo, a poet. Brian Arreola, Jason Wickson Marcello, a painter . Justin Moore, Kenneth Pereira Colline, a philosopher . Max Wier, Miroslaw Witkowski Schaunard, a musician . Adonis Abuyen, Mark Davies Benoit, their landlord . .Joseph “Bill” Kloppenburg, Chaz Nailor Mimi, a seamstress . Joanna Ruzsała, Jung Nan Yoon Two delivery boys . Nick Palmer, Evan James Snipes Parpignol, a toy vendor . Hong-Teak Lim Musetta, friend of Marcello . Rebecca Fay, Laura Waters Alcindoro, a state councilor . Joseph “Bill” Kloppenburg, Chaz Nailor Customs Guard . Nathan Brown Sergeant . .Cody Medina People of the Latin Quarter Vendors . Korey Gonzalez, Olivia Hairston, Wayne Hu, Kimberly Izzo, David Johnson, Daniel Lentz, William Lockhart, Cody Medina, Abigail Peters, Lauren Pickett, Shelley Ploss, Jerome Sibulo, Kris Simmons Middle Class . Jacqueline Brecheen, Molly Fetherston, Lawrence Galera, Chris Gobles, Jonathan Hilber, Kira McGirr, Justin Merrick, Kevin Necciai, Naomi Ruiz, Jason Thomas Elegant Ladies . -

Grand Finals Concert

NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Metropolitan Opera Carlo Rizzi National Council Auditions host Grand Finals Concert Anthony Roth Costanzo Sunday, March 31, 2019 3:00 PM guest artist Christian Van Horn Metropolitan Opera Orchestra The Metropolitan Opera National Council is grateful to the Charles H. Dyson Endowment Fund for underwriting the Council’s Auditions Program. general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Carlo Rizzi host Anthony Roth Costanzo guest artist Christian Van Horn “Dich, teure Halle” from Tannhäuser (Wagner) Meghan Kasanders, Soprano “Fra poco a me ricovero … Tu che a Dio spiegasti l’ali” from Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizetti) Dashuai Chen, Tenor “Oh! quante volte, oh! quante” from I Capuleti e i Montecchi (Bellini) Elena Villalón, Soprano “Kuda, kuda, kuda vy udalilis” (Lenski’s Aria) from Today’s concert is Eugene Onegin (Tchaikovsky) being recorded for Miles Mykkanen, Tenor future broadcast “Addio, addio, o miei sospiri” from Orfeo ed Euridice (Gluck) over many public Michaela Wolz, Mezzo-Soprano radio stations. Please check “Seul sur la terre” from Dom Sébastien (Donizetti) local listings. Piotr Buszewski, Tenor Sunday, March 31, 2019, 3:00PM “Captain Ahab? I must speak with you” from Moby Dick (Jake Heggie) Thomas Glass, Baritone “Don Ottavio, son morta! ... Or sai chi l’onore” from Don Giovanni (Mozart) Alaysha Fox, Soprano “Sorge infausta una procella” from Orlando (Handel) -

![[T] IMRE PALLÓ](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5305/t-imre-pall%C3%B3-725305.webp)

[T] IMRE PALLÓ

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs FRANZ (FRANTISEK) PÁCAL [t]. Leitomischi, Austria, 1865-Nepomuk, Czechoslo- vakia, 1938. First an orchestral violinist, Pácal then studied voice with Gustav Walter in Vienna and sang as a chorister in Cologne, Bremen and Graz. In 1895 he became a member of the Vienna Hofoper and had a great success there in 1897 singing the small role of the Fisherman in Rossini’s William Tell. He then was promoted to leading roles and remained in Vienna through 1905. Unfor- tunately he and the Opera’s director, Gustav Mahler, didn’t get along, despite Pacal having instructed his son to kiss Mahler’s hand in public (behavior Mahler considered obsequious). Pacal stated that Mahler ruined his career, calling him “talentless” and “humiliating me in front of all the Opera personnel.” We don’t know what happened to invoke Mahler’s wrath but we do know that Pácal sent Mahler a letter in 1906, unsuccessfully begging for another chance. Leaving Vienna, Pácal then sang with the Prague National Opera, in Riga and finally in Posen. His rare records demonstate a fine voice with considerable ring in the upper register. -Internet sources 1858. 10” Blk. Wien G&T 43832 [891x-Do-2z]. FRÜHLINGSZEIT (Becker). Very tiny rim chip blank side only. Very fine copy, just about 2. $60.00. GIUSEPPE PACINI [b]. Firenze, 1862-1910. His debut was in Firenze, 1887, in Verdi’s I due Foscari. In 1895 he appeared at La Scala in the premieres of Mascagni’s Guglielmo Ratcliff and Silvano. Other engagements at La Scala followed, as well as at the Rome Costanzi, 1903 (with Caruso in Aida) and other prominent Italian houses. -

I Clubs Della Divisione 2 Sicilia Del Kiwanis International Tra Gli

http://lnx.archiviodistrettokiwanis.it/2019/news.php?item.746 Pagina 1/7 I Clubs della Divisione 2 Sicilia del Kiwanis International tra gli sponsor della 52a edizione del Premio Bellini d oro admin, 17 settembre 2020, 15:04 Catania, 16/9/2020. Bellissima serata ieri al Teatro Massimo Bellini di Catania per la 52a edizione del prestigioso Premio Bellini d'oro 2020, entrato a far parte del Bellini Renaissance. Il Premio, organizzato dalla Società Catanese Amici della Musica (SCAM), presidente e direttrice artistica Anna Rita Fontana, in collaborazione con il Teatro Massimo Bellini, sovrintendente Giovanni Cultrera, negli anni è andato a grandi personalità del mondo dell opera lirica fra le quali ricordiamo Joan Sutherland, Renata Scotto, Montserrat Caballé, Cecilia Bartoli, Alfred Krauss, Franco Corelli, Giuseppe Di Stefano, Luciano Pavarotti, Salvatore Fisichella e Riccardo Muti. Quest anno è stato conferito alla memoria di due figure di rilievo del mondo musicale siciliano: Antonio Maugeri, fondatore dello stesso premio e per oltre vent anni presidente della SCAM e al tenore augustano di fama internazionale, Marcello Giordani, entrambi scomparsi prematuramente nel 2019. Marcello Guagliardo, in arte Giordani, era kiwaniano, socio del KC Augusta. La serata è stata impreziosita dall altissima professionalità del soprano Clara Polito, del baritono Giovanni Guagliardo (nipote di Giordani) e dall orchestra del Bellini diretta da Antonio Manuli. I Clubs della Divisione 2 Sicilia Etna Patrimonio dell Umanità sono stati tra gli sponsor della serata. Sponsor della serata anche la Divisione 3 Sicilia sud-est, rappresentata dal Luogotenente Gov. Ciro Messina, il KC Augusta, rappresentato dal Presidente Franco Rattizzato e l Associazione musicale "Maestro Francesco Musmarra", rappresentata dalla dottoressa Vera Torrisi. -

22 Years of Crown 'Mic Memos'

Web: http://www.pearl-hifi.com 86008, 2106 33 Ave. SW, Calgary, AB; CAN T2T 1Z6 E-mail: [email protected] Ph: +.1.403.244.4434 Fx: +.1.403.245.4456 Inc. Perkins Electro-Acoustic Research Lab, Inc. ❦ Engineering and Intuition Serving the Soul of Music Please note that the links in the PEARL logotype above are “live” and can be used to direct your web browser to our site or to open an e-mail message window addressed to ourselves. To view our item listings on eBay, click here. To see the feedback we have left for our customers, click here. This document has been prepared as a public service . Any and all trademarks and logotypes used herein are the property of their owners. It is our intent to provide this document in accordance with the stipulations with respect to “fair use” as delineated in Copyrights - Chapter 1: Subject Matter and Scope of Copyright; Sec. 107. Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair Use. Public access to copy of this document is provided on the website of Cornell Law School at http://www4.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.html and is here reproduced below: Sec. 107. - Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair Use Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, includ- ing such use by reproduction in copies or phono records or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for class- room use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. -

Opera Wrocławska

OPERA WROCŁAWSKA ~ INSTYTUCJA KULTURY SAMORZĄDU WOJEWÓDZTWA DOLNOSLĄSKIEGO WSPÓŁPROWADZONA PRZEZ MINISTRA KULTURY I DZIEDZICTWA NARODOWEGO EWA MICHNIK DYREKTOR NAUELNY I ARTYSTYUNY STRASZNY DWÓR THE HAUNTED MANOR STANISŁAW MONIUSZKO OPERA W 4 AKTACH I OPERA IN 4 ACTS JAN CHĘCIŃSKI LIBR ETIO WARSZAWA, 1865 PRAPREMIERA I PREVIEW SPEKTAKLE PREMIEROWE I PREMIERES 00 PT I FR 6 111 2009 I 19 SO I SA 7 Ili 2009 I 19 00 00 ND I SU 8 Ili 2009 117 CZAS TRWANIA SPEKTAKLU 180 MIN. I DURATION 180 MIN . 1 PRZERWA I 1 PAUSE SPEKTAKL WYKONYWANY JEST W JĘZYKU POLSKIM Z POLSKIMI NAPISAMI POLI SH LANGUAGE VERSION WITH SURTITLES STRASZNY DWÓR I THE HAU~TED MAl\ OR REALIZATO RZY I PRODUCERS OBSADA I CAST REALIZATORZY I PROOUCERS MIECZNIK MACIEJ TOMASZ SZREDER ZBIGNIEW KRYCZKA JAROSŁAW BODAKOWSKI KIEROWNICTWO MUZYCZNE, DYRYGENT I MUSICAL DIRECTION, CONDUCTOR BOGUSŁAW SZYNALSKI* JACEK JASKUŁA LACO ADAMIK STEFAN SKOŁUBA INSCENIZACJA I REŻYSERIA I STAGE DIRECTION RAFAŁ BARTMIŃSKI* WIKTOR GORELIKOW ARNOLD RUTKOWSKI* RADOSŁAW ŻUKOWSKI BARBARA KĘDZIERSKA ALEKSANDER ZUCHOWICZ* SCENOGRAFIA I SET & COSTUME DESIGNS DAMAZY ZBIGNIEW ANDRZEJ KALININ MAGDALENA TESŁAWSKA, PAWEŁ GRABARCZYK DAMIAN KONIECZEK KAROL KOZŁOWSKI WSPÓŁPRACA SCENOGRAFICZNA I SET & COSTUME DE SIGNS CO-OPERATION TOMASZ RUDNICKI EDWARD KULCZYK RAFAŁ MAJZNER HENRYK KONWIŃSKI HANNA CHOREOGRAFIA I CHOREOGRAPHY EWA CZERMAK STARSZA NIEWIASTA ALEKSANDRA KUBAS JOLANTA GÓRECKA MAŁGORZATA ORAWSKA JOANNA MOSKOWICZ PRZYGOTOWANIE CHÓRU I CHORUS MASTER MARTA JADWIGA URSZULA CZUPRYŃSKA BOGUMIŁ PALEWICZ ANNA BERNACKA REŻYSERIA ŚWIATEŁ I LIGHTING DESIGNS DOROT A DUTKOWSKA GRZEŚ PIOTR BUNZLER HANNA MARASZ CZEŚNIKOWA ASYSTENT REŻYS ERA I ASS ISTAN T TO THE STAGE DIRECTOR BARBARA BAGIŃSKA SOLIŚCI, ORKIESTRA, CHÓR I BALET ELŻBIETA KACZMARZYK-JANCZAK OPERY WROCŁAWSKIEJ, STATYŚCI ADAM FRONTCZAK, JULIAN ŻYCHOWICZ ALEKSANDRA LEMISZKA SOLOISTS, ORCHESTRA, CHOIR AND BALLET INSPICJENCI I SRTAGE MANAGERS OF THE WROCŁAW OPERA, SUPERNUMERARIES * gościnnie I spec1al guest Dyrekcja zastrzega sobie prawo do zmian w obsadach . -

Bando Bellini2005

COMUNE DI REGIONE SICILIANA PROVINCIA REGIONALE REGIONE SICILIANA CALTANISSETTA ASS.REG. BB.CC. e P.I. DI CALTANISSETTA ASS.REG. TURISMO SPORT E SPETTACOLO ASSOCIAZIONE AMICI DELLA MUSICA CALTANISSETTA - ITALY 42° CONCORSO INTERNAZIONALE «VINCENZO BELLINI» PER CANTANTI LIRICI FOR OPERA SINGERS - POUR CHANTEURS LYRIQUES Nel 210° anniversario della nascita del grande compositore siciliano 14-20 NOVEMBRE 2011 SOTTO GLI AUSPICI: Comune di Caltanissetta Provincia Regionale di Caltanissetta Assessorato Regionale al Turismo e Spettacolo Ministero per i Beni le Attività culturali Segreteria: Concorso Internazionale «V. Bellini» M° Giuseppe Pastorello - Viale Trieste, 308 93100 CALTANISSETTA (ITALY) Tel. 0934 / 592025 - 554688 - Fax 0934 / 592025 E-mail: [email protected] - Sito Internet: www.concorsobellini.eu BREVE STORIA DEL CONCORSO INTERNAZIONALE «VINCENZO BELLINI» PER CANTANTI LIRICI Il Concorso, istituito sin dal 1965, fu inizialmente a carattere interregionale. Successivamente, fu dedicato ad una giovane pianista nissena, “Marisa CANCELLIE- RE” e quindi dal 1976, dedicato al musicista siciliano “Salvatore ALLEGRA”. Nel 1979 il Concorso è diventato Internazionale ed è stato dedicato al grande musicista siciliano Vincenzo Bellini” con articolazioni nelle due sezioni di pianoforte e canto. Sin dal 1977 viene istituito il Premio Speciale “M. CALLAS” che viene assegnato per la prima volta nel 1978 al soprano Gloria Guidi, 1981 al soprano Maria DRAGONI, che nel 1983 vinse il Premio “CALLAS” Televisivo. Nel 1982 viene assegnato al soprano greco Jenny DRIVALA alla quale viene assegnato anche il 1° premio assoluto. Lo stesso avviene nel 1984 per il soprano giapponese Kumi INAGAKI. Il Concorso “V. Bellini” ha laureato pianisti come, Giorgia TOMASSI - Judy CHIN- Bernd GLEMSER - Valeriu ROGA- CEV Giampaolo STUANI - Paola BRUNI - Andrea LUCCHESINI - Serghei HEROKI- NE e cantanti quali: Clarry BARTHA – Simone ALAIMO Valeria ESPOSITO - Olga ROMANKO Renata DALTIN - Ramon VARGAS - Elisabetta FIORILLO - Akemi SAKAMOTO Desireé RANCATORE ed altri. -

Edgardo Rocha

E DGARDO R OCHA TENOR Edgardo Rocha was born in Rivera, Uruguay, where he graduated in piano, studied choral-orchestral conducting at the University of the Republic and began his voice preparation with Beatriz Pazos and Raquel Pierotti. He moved 2008 to Italy, where he studied with the prestigious tenor Salvatore Fisichella and attended the Rossini-Master Classes of the tenor Rockwell Blake and of the baritone Alessandro Corbelli. He is the winner of several singing competitions including the 51th Competition of Young Musicians of the Uruguay, Maria Callas International Singing Competition in Sao Paulo, (Brazil), Giulio Neri Competition in Siena (Italy) and the First Stage Competition in Cesena, (Italy), where he debuted the role of Almaviva in Il barbiere di Siviglia by Rossini. Edgardo Rocha was Don Ramiro in the film La Cenerentola una favola in diretta, produced by Andrea Anderman for the Rai Television and broadcasted Live in Mondovision in June 2012, directed by Carlo Verdone and conducted by Gianluigi Gelmetti. In 2010, at the Festival della Valle d’Itria Martina Franca, he made his debut as Donizetti’s Gianni di Parigi, role written for the great tenor Giovanni Battista Rubini. Due to the obtained success, he began his career in Italy and abroad. He sang Gianni di Parigi at the Wexford Festival, La Cenerentola at the Teatro Lirico Cagliari, Bergen Festival, Seattle Opera, Opera di Stuttgart, Teatro Maestranza di Siviglia, Beaune Festival, Lausanne, Bilbao, Montecarlo, Dortmunt, Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, Concergebawn Amsterdam, Luzern Festival, Auditorio de Madrid, and Opera de Versailles, Don Pasquale at the Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino and Filarmonico di Verona, Così fan tutte at the Teatro San Carlo Napoli and Teatro Regio Torino, L’italiana in Algeri at Teatro Petruzzelli Bari, Wiener Staatsoper, Opera de Nancy, La scala di seta and Rossini’s Otello (as Jago next to Cecilia Bartoli) at the Opernhaus Zürich. -

1 CRONOLOGIA LICEISTA S'inclou Una Llista Amb Les Representaciones

CRONOLOGIA LICEISTA S’inclou una llista amb les representaciones de Rigoletto de Verdi en la història del Gran Teatre del Liceu. Estrena absoluta: 11 de març de 1851 al teatre La Fenice de Venècia Estrena a Barcelona i al Liceu: 3 de desembre de 1853 Última representació: 5 de gener del 2005 Total de representacions: 362 TEMPORADA 1853-1854 3-XII-1853 RIGOLETTO Llibret de Francesco Maria Piave. Música de Giuseppe Verdi. Nombre de representacions: 25 Núm. històric: de l’1 al 25. Dates: 3, 4, 8, 11, 15, 22, 23, 25, 26 desembre 1853; 5, 6, 12, 15, 19, 31 gener; 7, 12, 26 febrer; 1, 11, 23 març; 6, 17 abril; 16 maig; 2 juny 1854. Duca di Mantova: Ettore Irfré Rigoletto: Antonio Superchi Gilda: Amalia Corbari Sparafucile: Agustí Rodas Maddalena: Antònia Aguiló-Donatutti Giovanna: Josefa Rodés Conte di Monterone: José Aznar / Luigi Venturi (17 abril) Marullo: Josep Obiols Borsa: Luigi Devezzi Conte di Ceprano: Francesc Sánchez Contessa di Ceprano: Cristina Arrau Usciere: Francesc Nicola Paggio: Josefa Garriche Director: Eusebi Dalmau TEMPORADA 1854-1855 Nombre de representacions: 8 Número històric al Liceu: 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 Dates: 7, 10, 18 febrer; 13 març; 17 abril; 17, 27 maig; 7 juny 1855. Nota: Felice Varesi havia estat el primer Rigoletto a l'estrena mundial a la Fenice de Venècia l'11 de març de 1851. Duca di Mantova: Giacomo Galvani Rigoletto: Felice Varesi Gilda: Virginia Tilli Sparafucile: Agustí Rodas Maddalena: Matilde Cavalletti / Antònia Aguiló-Donatutti (7 de juny) Giovanna: Sra. Sotillo Conte di Monterone: Achille Rossi 1 Marullo: Josep Obiols Borsa: Josep Grau Contessa di Ceprano: Antònia Aguiló-Donatutti Director: Gabriel Balart TEMPORADA 1855-1856 L'òpera és anunciada com "Il Rigoletto". -

Lato 2011Lato

cena 16 zł 16 cena ISSN 1732-6125 200 lat Szkoły Dramatycznej w Warszawie / Osterloff / Rogacki /miasto / Miłobędzki / Coldwell / Lorent (5% VAT) (5% lato2011 pismo warszawskich uczelni artystycznych Wystawa końcoworoczna w ASP w Warszawie. Fot. Magda Sykulska Na okładce: Otto Axer, szkic kostiumu dla Aleksan- dra Zelwerowicza w roli Czubukowa w Oświadczy- nach Czechowa, reż. Henryk Szletyński, Teatr pismo Wojska Polskiego w Łodzi (na drugiej scenie warszawskich TWP – Teatru Powszechnego), premiera 6 lutego 1947. Własność prywatna, reprodukcja ze zbiorów uczelni Barbary Osterloff. artystycznych lato 2011 s. 2 Barbara Osterloff s. 40 Krzysztof Szyrszeń s. 70 Czucia, pasje i namiętności... Polska – Łotwa. Streszczenia Od Państwowego Instytutu Sztuki Relacje kulturalne w dziedzinie Summaries Teatralnej do Akademii Teatralnej muzyki i teatru (część pierwsza) Feelings, Passions and Infatuations… Poland – Latvia. Intercultural Relations in the Fields From the State Institute of Theatre Arts of Music and Theatre (Part One) s. 78 to the Theatre Academy Kalendarium Chronicle of Events s. 46 Małgorzata Komorowska s. 8 Henryk Izydor Rogacki O śpiewie w Polsce dawniej i dziś Repertuar mistrza Singing in Poland, Past and Present Master’s Repertoire s. 52 Piotr Kędzierski s. 14 Uczeniu się nigdy nie ma końca... Rzeczywistość architektury. czyli o muzyce na co dzień w XIX wieku Problem miasta Learning Never Ends... Or Everyday Music in the 19th Z Maciejem Miłobędzkim, Century architektem pracowni JEMS, której dziełem jest właśnie realizowany projekt nowego kompleksu budynków s. 56 Aleksandra Grzelak ASPIRACJE lato / summer 2011 ASP w Warszawie, rozmawia David Mamet o aktorze Pismo warszawskich uczelni artystycznych Journal of Warsaw Schools of Arts Magdalena Sołtys David Mamet on the Actor Reality of Architecture.