Quantifying the Association of Self-Enhancement Bias with Self- Ratings of Personality and Life Satisfaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Task-Based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information Visualization

A Task-based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information Visualization Evanthia Dimara, Steven Franconeri, Catherine Plaisant, Anastasia Bezerianos, and Pierre Dragicevic Three kinds of limitations The Computer The Display 2 Three kinds of limitations The Computer The Display The Human 3 Three kinds of limitations: humans • Human vision ️ has limitations • Human reasoning 易 has limitations The Human 4 ️Perceptual bias Magnitude estimation 5 ️Perceptual bias Magnitude estimation Color perception 6 易 Cognitive bias Behaviors when humans consistently behave irrationally Pohl’s criteria distilled: • Are predictable and consistent • People are unaware they’re doing them • Are not misunderstandings 7 Ambiguity effect, Anchoring or focalism, Anthropocentric thinking, Anthropomorphism or personification, Attentional bias, Attribute substitution, Automation bias, Availability heuristic, Availability cascade, Backfire effect, Bandwagon effect, Base rate fallacy or Base rate neglect, Belief bias, Ben Franklin effect, Berkson's paradox, Bias blind spot, Choice-supportive bias, Clustering illusion, Compassion fade, Confirmation bias, Congruence bias, Conjunction fallacy, Conservatism (belief revision), Continued influence effect, Contrast effect, Courtesy bias, Curse of knowledge, Declinism, Decoy effect, Default effect, Denomination effect, Disposition effect, Distinction bias, Dread aversion, Dunning–Kruger effect, Duration neglect, Empathy gap, End-of-history illusion, Endowment effect, Exaggerated expectation, Experimenter's or expectation bias, -

Ilidigital Master Anton 2.Indd

services are developed to be used by humans. Thus, understanding humans understanding Thus, humans. by used be to developed are services obvious than others but certainly not less complex. Most products bioengineering, and as shown in this magazine. Psychology mightbusiness world. beBe it more the comparison to relationships, game elements, or There are many non-business flieds which can betransfered to the COGNTIVE COGNTIVE is key to a succesfully develop a product orservice. is keytoasuccesfullydevelopproduct BIASES by ANTON KOGER The Power of Power The //PsychologistatILI.DIGITAL WE EDIT AND REINFORCE SOME WE DISCARD SPECIFICS TO WE REDUCE EVENTS AND LISTS WE STORE MEMORY DIFFERENTLY BASED WE NOTICE THINGS ALREADY PRIMED BIZARRE, FUNNY, OR VISUALLY WE NOTICE WHEN WE ARE DRAWN TO DETAILS THAT WE NOTICE FLAWS IN OTHERS WE FAVOR SIMPLE-LOOKING OPTIONS MEMORIES AFTER THE FACT FORM GENERALITIES TO THEIR KEY ELEMENTS ON HOW THEY WERE EXPERIENCED IN MEMORY OR REPEATED OFTEN STRIKING THINGS STICK OUT MORE SOMETHING HAS CHANGED CONFIRM OUR OWN EXISTING BELIEFS MORE EASILY THAN IN OURSELVES AND COMPLETE INFORMATION way we see situations but also the way we situationsbutalsotheway wesee way the biasesnotonlychange Furthermore, overload. cognitive avoid attention, ore situations, guide help todesign massively can This in. take people information of kind explainhowandwhat ofperception egory First,biasesinthecat andappraisal. ory, self,mem perception, into fourcategories: roughly bedivided Cognitive biasescan within thesesituations. forusers interaction andeasy in anatural situationswhichresults sible toimprove itpos and adaptingtothesebiasesmakes ingiven situations.Reacting ways certain act sively helpstounderstandwhypeople mas into consideration biases ing cognitive Tak humanbehavior. topredict likely less or andmore relevant illusionsare cognitive In each situation different every havior day. -

Infographic I.10

The Digital Health Revolution: Leaving No One Behind The global AI in healthcare market is growing fast, with an expected increase from $4.9 billion in 2020 to $45.2 billion by 2026. There are new solutions introduced every day that address all areas: from clinical care and diagnosis, to remote patient monitoring to EHR support, and beyond. But, AI is still relatively new to the industry, and it can be difficult to determine which solutions can actually make a difference in care delivery and business operations. 59 Jan 2021 % of Americans believe returning Jan-June 2019 to pre-coronavirus life poses a risk to health and well being. 11 41 % % ...expect it will take at least 6 The pandemic has greatly increased the 65 months before things get number of US adults reporting depression % back to normal (updated April and/or anxiety.5 2021).4 Up to of consumers now interested in telehealth going forward. $250B 76 57% of providers view telehealth more of current US healthcare spend % favorably than they did before COVID-19.7 could potentially be virtualized.6 The dramatic increase in of Medicare primary care visits the conducted through 90% $3.5T telehealth has shown longevity, with rates in annual U.S. health expenditures are for people with chronic and mental health conditions. since April 2020 0.1 43.5 leveling off % % Most of these can be prevented by simple around 30%.8 lifestyle changes and regular health screenings9 Feb. 2020 Apr. 2020 OCCAM’S RAZOR • CONJUNCTION FALLACY • DELMORE EFFECT • LAW OF TRIVIALITY • COGNITIVE FLUENCY • BELIEF BIAS • INFORMATION BIAS Digital health ecosystems are transforming• AMBIGUITY BIAS • STATUS medicineQUO BIAS • SOCIAL COMPARISONfrom BIASa rea• DECOYctive EFFECT • REACTANCEdiscipline, • REVERSE PSYCHOLOGY • SYSTEM JUSTIFICATION • BACKFIRE EFFECT • ENDOWMENT EFFECT • PROCESSING DIFFICULTY EFFECT • PSEUDOCERTAINTY EFFECT • DISPOSITION becoming precise, preventive,EFFECT • ZERO-RISK personalized, BIAS • UNIT BIAS • IKEA EFFECT and • LOSS AVERSION participatory. -

The Psychology of Competition: a Social Comparison Perspective

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 11-2013 The Psychology of Competition: A Social Comparison Perspective Stephen M. Garcia Avishalom Tor Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Tyrone M. Schiff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Behavior and Behavior Mechanisms Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Stephen M. Garcia, Avishalom Tor & Tyrone M. Schiff, The Psychology of Competition: A Social Comparison Perspective, 8 Persp on Psych Sci 634 (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/941 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PPSXXX10.1177/1745691613504114Garcia et al.Psychology of Competition 504114research-article2013 Perspectives on Psychological Science XX(X) 1 –17 The Psychology of Competition: © The Author(s) 2013 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav A Social Comparison Perspective DOI: 10.1177/1745691613504114 pps.sagepub.com Stephen M. Garcia1, Avishalom Tor2, and Tyrone M. Schiff1 1University of Michigan and 2University of Notre Dame Abstract Social comparison—the tendency to self-evaluate by comparing ourselves to others—is an important source of competitive behavior. We propose a new model that distinguishes between individual and situational factors that increase social comparison and thus lead to a range of competitive attitudes and behavior. Individual factors are those that vary from person to person: the relevance of the performance dimension, the similarity of rivals, and their relationship closeness to the individual, as well as the various individual differences variables relating to social comparison more generally. -

John Collins, President, Forensic Foundations Group

On Bias in Forensic Science National Commission on Forensic Science – May 12, 2014 56-year-old Vatsala Thakkar was a doctor in India but took a job as a convenience store cashier to help pay family expenses. She was stabbed to death outside her store trying to thwart a theft in November 2008. Bloody Footwear Impression Bloody Tire Impression What was the threat? 1. We failed to ask ourselves if this was a footwear impression. 2. The appearance of the impression combined with the investigator’s interpretation created prejudice. The accuracy of our analysis became threatened by our prejudice. Types of Cognitive Bias Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_cognitive_biases | Accessed on April 14, 2014 Anchoring or focalism Hindsight bias Pseudocertainty effect Illusory superiority Levels-of-processing effect Attentional bias Hostile media effect Reactance Ingroup bias List-length effect Availability heuristic Hot-hand fallacy Reactive devaluation Just-world phenomenon Misinformation effect Availability cascade Hyperbolic discounting Recency illusion Moral luck Modality effect Backfire effect Identifiable victim effect Restraint bias Naive cynicism Mood-congruent memory bias Bandwagon effect Illusion of control Rhyme as reason effect Naïve realism Next-in-line effect Base rate fallacy or base rate neglect Illusion of validity Risk compensation / Peltzman effect Outgroup homogeneity bias Part-list cueing effect Belief bias Illusory correlation Selective perception Projection bias Peak-end rule Bias blind spot Impact bias Semmelweis -

Implicit Bias and Moral Analysis: Continuing to Traverse the Moral Terrain of Community Development

Implicit Bias and Moral Analysis: Continuing to Traverse the Moral Terrain of Community Development Peter A. DePergola II, Ph.D., M.T.S. Director of Clinical Ethics, Baystate Health Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School Assistant Professor of Bioethics and Medical Humanities, Elms College Director, Center for Ethics, Religion, and Culture, Elms College Adjunct Assistant Professor of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine Research Scientist in Neuroethics, American Academy of Neurology Research Scholar in Bioethics, TEDMED Objectives • Identify the relevant questions of moral analysis and moral reasoning in the context of community development. • Examine sources of implicit bias in the context of distributing limited goods. • Discuss methods by which to identify and remedy implicit bias in the context of serving others. • Distinguish between caring for a person with needs and caring for the needs a person has. Relevant Questions of Moral Analysis • “What?” (Veracity) • “Why?” and “How?” (Beneficence, Nonmaleficence) • “Who?” (Dignity, Autonomy) • “When?” and “Where?” (Justice, Privacy, Confidentiality) • “What if…?” (Prudence) • “What else?” (Fidelity, Courage) Relevant Questions of Moral Reasoning 1. What are we attempting to do? (Is our plan for serving persons in need ethically, legally, and practically reasonable?) 2. Why are we attempting to do it? (Is our plan for serving persons in need focused on the overall well-being of those in need?) 3. How are we attempting to do it? (Is the method of serving persons in need proportionate to the goals we had for serving them in the first place?) 4. What do we intend in attempting to do it? (Is our plan for serving persons in need emerging from a place of benevolence?) 5. -

To Err Is Human, but Smaller Funds Can Succeed by Mitigating Cognitive Bias

FEATURE | SMALLER FUNDS CAN SUCCEED BY MITIGATING COGNITIVE BIAS To Err Is Human, but Smaller Funds Can Succeed by Mitigating Cognitive Bias By Bruce Curwood, CIMA®, CFA® he evolution of investment manage 2. 2000–2008: Acknowledgement, where Diversification meant simply expanding the ment has been a long and painful plan sponsors discovered the real portfolio beyond domestic markets into T experience for many institutional meaning of risk. lesscorrelated foreign equities and return plan sponsors. It’s been trial by fire and 3. Post2009: Action, which resulted in a was a simple function of increasing the risk learning important lessons the hard way, risk revolution. (more equity, increased leverage, greater generally from past mistakes. However, foreign currency exposure, etc.). After all, “risk” doesn’t have to be a fourletter word Before 2000, modern portfolio theory, history seemed to show that equities and (!@#$). In fact, in case you haven’t noticed, which was developed in the 1950s and excessive risk taking outperformed over the there is currently a revolution going on 1960s, was firmly entrenched in academia long term. In short, the crux of the problem in our industry. Most mega funds (those but not as well understood by practitioners, was the inequitable amount of time and wellgoverned funds in excess of $10 billion whose focus was largely on optimizing effort that investors spent on return over under management) already have moved return. The efficient market hypothesis pre risk, and that correlation and causality were to a more comprehensive risk management vailed along with the rationality of man, supposedly closely linked. -

Cognitive Biases in Fitness to Practise Decision-Making

ADVICE ON BIASES IN FITNESS TO PRACTISE DECISION-MAKING IN ACCEPTED OUTCOME VERSUS PANEL MODELS FOR THE PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AUTHORITY Prepared by: LESLIE CUTHBERT Date: 31 March 2021 Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................. 2 Background .................................................................................................. 2 Purpose of the advice.................................................................................... 3 Summary of conclusions ................................................................................ 4 Documents considered .................................................................................. 4 Technical terms and explanations ................................................................... 5 Disclaimer .................................................................................................... 5 II. How biases might affect the quality of decision-making in the AO model, as compared to the panel model .............................................................................. 6 Understanding cognitive biases in fitness to practise decision-making ............... 6 Individual Decision Maker (e.g. a Case Examiner) in AO model ......................... 8 Multiple Case Examiners .............................................................................. 17 Group Decision Maker in a Panel model of 3 or more members ....................... 22 III. Assessment of the impact of these biases, -

Taking Behavioralism Seriously: the Problem of Market Manipulation

TAKING BEHAVIORALISM SERIOUSLY: THE PROBLEM OF MARKET MANIPULATION JON D. HANSON* & DOUGLAS A. KYSAR** In recent years, legal scholars dissatisfied with the behavioral assumptions of the rationalactor model have increasingly turned to the findings of cognitive psycholo- gists and decision theorists to enhance the accuracy of efficiency analysis. Jon Hanson and Douglas Kysar review those findings in this Article, concluding that scholars have been well justified in incorporating the behaviorallst account of human behavior into law and economics. Nevertheless, Hanson and Kysar argue that those scholars simultaneously have failed to take the findings of behavioral researchto their logical conclusion. Using the scholarly application of behavioral- ist insights to products liability theory as an example, the authors demonstrate that legal scholars thus far have treated cognitive anomalies as relatively fixed and independent influences on individualdecisionmaking. Rather than such an exoge- nous analysis, Hanson and Kysar advocate an endogenous examination of behavi- oralistfindings that allows for internal, dynamic effects of cognitive biases within the decisionmaking model. By recognizing that cognitive anomalies influence not only the behavior of biased decisionmakers but also the incentives of other eco- nomic actors, Hanson and Kysar reveal the possibility of market manipulation- that is, the possibility that market outcomes can be influenced, if not determined, by the ability of one actor to control the format of information, the framing and pres- entation of choices, and, more generally, the setting within which market transac- tions occur. Again using the field of products liability theory as an example, the authors argue that such market manipulation will come to characterize consumer product markets; powerful economic incentives will drive manufacturers to engage in practices that, whether consciously or not, utilize non-rationalconsumer tenden- cies to influence consumer preferences and perceptionsfor gain. -

Request for Information ) Energy Cons

Before the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Re: Request for Information ) Energy Conservation Program: ) Energy Conservation Standards for ) EERE–2017–BT–STD–0003 Consumer Refrigerators, ) Refrigerator Freezers, and Freezers ) Comments of Consumer Federation of America Mark Cooper Mel Hall-Crawford Director of Research Director of Energy Programs FEBRUARY 13, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT 1 A. Organizational Background of the Consumer Federation of America Relevant to the Above Captioned Proceeding B. A Pragmatic Consumer Approach to Setting Standards C. Outline 2. A LOOK AT THE REAL WORLD: THE TRACK RECORD OF APPLIANCE ENERGY 4 EFFICIENCY PERFORMANCE STANDARDS A. Simple Trends B. CFA’s Econometric Analysis of Appliances C. Prices D. The Benefits of Energy Efficiency Standard: Trump’s Two Trillion Dollar Mistake E. Low Income Consumers 1. Simple Mathematics of Income and Energy Consumption 2. Vulnerability to Market Imperfections 3. Exposure to Externalities 3. COMPREHENSIVE, MARKET FAILURE EXPLANATIONS OF THE EFFICIENCY GAP 17 A. The Efficiency Gap 1. The LBL Framework 2. The Resources for the Future Framework 3. The United Nations Industrial Development Organization B. Empirical Evidence of Market Barriers and Imperfections 1. Market Imperfections 2. Positive Externalities 3. Information and Behavior 4. Market Structure and Transaction Costs 4. STANDARDS AS A RESPONSE TO MARKET FAILURE 27 A. Rigorous Cost Benefit Analysis B. Standards as a Policy Response 1. Traditional Market Failures 2. Positive Externalities 3. Endemic Information and Behavior 4. Market Structure and Transaction Costs 5. COMMAND-BUT-NOT-CONTROL STANDARDS 31 A. Key Characteristics of Well-Crafted Performance Standards 1. -

List of Cognitive Biases

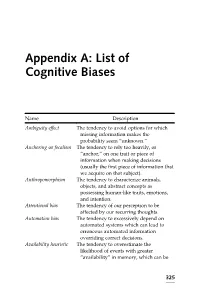

Appendix A: List of Cognitive Biases Name Description Ambiguity effect The tendency to avoid options for which missing information makes the probability seem “unknown.” Anchoring or focalism The tendency to rely too heavily, or “anchor,” on one trait or piece of information when making decisions (usually the first piece of information that we acquire on that subject). Anthropomorphism The tendency to characterize animals, objects, and abstract concepts as possessing human-like traits, emotions, and intention. Attentional bias The tendency of our perception to be affected by our recurring thoughts. Automation bias The tendency to excessively depend on automated systems which can lead to erroneous automated information overriding correct decisions. Availability heuristic The tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events with greater “availability” in memory, which can be 325 Appendix A: (Continued ) Name Description influenced by how recent the memories are or how unusual or emotionally charged they may be. Availability cascade A self-reinforcing process in which a collective belief gains more and more plausibility through its increasing repetition in public discourse (or “repeat something long enough and it will become true”). Backfire effect When people react to disconfirming evidence by strengthening their belief. Bandwagon effect The tendency to do (or believe) things because many other people do (or believe) the same. Related to groupthink and herd behavior. Base rate fallacy or The tendency to ignore base rate Base rate neglect information (generic, general information) and focus on specific information (information only pertaining to a certain case). Belief bias An effect where someone’s evaluation of the logical strength of an argument is biased by the believability of the conclusion. -

Cognitive Biases: an Alphabetical List

COGNITIVE BIASES: AN ALPHABETICAL LIST Adaptive bias With limited information, decisions are based around the costs of being wrong. Affect Heuristic A mental shortcut relying on emotion rather than logical thought Ambiguity Aversion Preferring known risks over unknown risks Anchor When individuals rely heavily on an initial piece of information, known as the "anchor", when making decisions. Association Bias see Illusory Superiority Attribution effect See Fundamental attribution error Authority Bias Tendency to give greater credence to the opinion of an authority figure, and be more influenced by them, regardless of their expertise. Availability heuristic People create a picture of the world using the examples that most easily come to mind – the vivid, emotional or unusual. Base-Rate fallacy The tendency to ignore ‘base’ or general information and focus on specific information. Black Swan Highly significant events that affect your life, your career, your company, your country. There are positive and negative Black Swans. Cognitive Biases: An alphabetical list Cherry-picking Selecting and showcasing the most attractive features and hiding the rest. Clustering illusion Overestimating the importance of small patterns in large samples of random data. Cognitive Dissonance Having inconsistent thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes and how the mind rationalises these inconsistencies Coincidence See Subjective Validation Confirmation Bias Interpreting information in a way that confirms one's preconceptions. Conjunction Fallacy Assumption that specific conditions are more probable than general ones. Contrast Effect How perceptions change in relation to contrasting objects. Correspondence bias See Fundamental attribution error Default Effect When given a choice between, people tend to favour the default option. Dunning–Kruger effect Unskilled individuals overestimate their abilities while experts underestimate theirs.