Living with Lovebugs1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invasive Insects (Adventive Pest Insects) in Florida1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. ENY-827 Invasive Insects (Adventive Pest Insects) in Florida1 J. H. Frank and M. C. Thomas2 What is an Invasive Insect? include some of the more obscure native species, which still are unrecorded; they do not include some The term 'invasive species' is defined as of the adventive species that have not yet been 'non-native species which threaten ecosystems, detected and/or identified; and they do not specify the habitats, or species' by the European Environment origin (native or adventive) of many species. Agency (2004). It is widely used by the news media and it has become a bureaucratese expression. This is How to Recognize a Pest the definition we accept here, except that for several reasons we prefer the word adventive (meaning they A value judgment must be made: among all arrived) to non-native. So, 'invasive insects' in adventive species in a defined area (Florida, for Florida are by definition a subset (those that are example), which ones are pests? We can classify the pests) of the species that have arrived from abroad more prominent examples, but cannot easily decide (adventive species = non-native species = whether the vast bulk of them are 'invasive' (= pests) nonindigenous species). We need to know which or not, for lack of evidence. To classify them all into insect species are adventive and, of those, which are pests and non-pests we must draw a line somewhere pests. in a continuum ranging from important pests through those that are uncommon and feed on nothing of How to Know That a Species is consequence to humans, to those that are beneficial. -

Heteroptera: Coreidae: Coreinae: Leptoscelini)

Brailovsky: A Revision of the Genus Amblyomia 475 A REVISION OF THE GENUS AMBLYOMIA STÅL (HETEROPTERA: COREIDAE: COREINAE: LEPTOSCELINI) HARRY BRAILOVSKY Instituto de Biología, UNAM, Departamento de Zoología, Apdo Postal 70153 México 04510 D.F. México ABSTRACT The genus Amblyomia Stål is revised and two new species, A. foreroi and A. prome- ceops from Colombia, are described. New host plant and distributional records of A. bifasciata Stål are given; habitus illustrations and drawings of male and female gen- italia are included as well as a key to the known species. The group feeds on bromeli- ads. Key Words: Insecta, Heteroptera, Coreidae, Leptoscelini, Amblyomia, Bromeliaceae RESUMEN El género Amblyomia Stål es revisado y dos nuevas especies, A. foreroi y A. prome- ceops, recolectadas en Colombia, son descritas. Plantas hospederas y nuevas local- idades para A. bifasciata Stål son incluidas; se ofrece una clave para la separación de las especies conocidas, las cuales son ilustradas incluyendo los genitales de ambos sexos. Las preferencias tróficas del grupo están orientadas hacia bromelias. Palabras clave: Insecta, Heteroptera, Coreidae, Leptoscelini, Amblyomia, Bromeli- aceae The neotropical genus Amblyomia Stål was previously known from a single Mexi- can species, A. bifasciata Stål 1870. In the present paper the genus is redefined to in- clude two new species collected in Colombia. This genus apparently is restricted to feeding on members of the Bromeliaceae, and specimens were collected on the heart of Ananas comosus and Aechmea bracteata. -

Distribution and Population Dynamics of the Asian Cockroach

DISTRIBUTION AND POPULATION DYNAMICS OF THE ASIAN COCKROACH (BLATTELLA ASAHINIA MIZUKUBO) IN SOUTHERN ALABAMA AND GEORGIA Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this thesis is my own or was done in collaboration with my advisory committee. This thesis does not include proprietary or classified information. ___________________________________ Edward Todd Snoddy Certificate of Approval: ___________________________ ___________________________ Micky D. Eubanks Arthur G. Appel, Chair Associate Professor Professor Entomology and Plant Pathology Entomology and Plant Pathology ___________________________ ___________________________ Xing Ping Hu George T. Flowers Associate Professor Interim Dean Entomology and Plant Pathology Graduate School DISTRIBUTION AND POPULATION DYNAMICS OF THE ASIAN COCKROACH (BLATTELLA ASAHINIA MIZUKUBO) IN SOUTHERN ALABAMA AND GEORGIA Edward Todd Snoddy A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Auburn, Alabama May 10, 2007 DISTRIBUTION AND POPULATION DYNAMICS OF THE ASIAN COCKROACH (BLATTELLA ASAHINIA MIZUKUBO) IN SOUTHERN ALABAMA AND GEORGIA Edward Todd Snoddy Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this thesis at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions and at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights. _______________________ Signature of Author _______________________ Date of Graduation iii VITA Edward Todd Snoddy was born in Auburn, Alabama on February 28, 1964 to Dr. Edward Lewis Snoddy and Lucy Mae Snoddy. He graduated Sheffield High School, Sheffield, Alabama in 1981. He attended Alexander Junior College from 1981 to 1983 at which time he transferred to Auburn University. He married Tracy Smith of Uchee, Alabama in 1984. -

LOUISIANA SCIENTIST Vol. 1A No. 3

LOUISIANA SCIENTIST THE NEWSLETTER of the LOUISIANA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Volume 1A, No. 3 (2007 Annual Meeting Abstracts) Published by THE LOUISIANA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES 15 June 2012 Louisiana Academy of Sciences Abstracts of Presentations 2007 Annual Meeting Southern University and A&M College Baton Rouge, Louisiana 16 March 2007 Table of Contents Division/Section Page Division of Agriculture, Forestry, and Wildlife . 5 Division of Biological Sciences . 11 Botany Section . 11 Environmental Sciences Section . 11 Microbiology Section . 17 Molecular and Biomedical Biology Section . 21 Zoology Section . 23 Division of Physical Sciences . 28 Chemistry Section . 28 Computer Science Section . 34 Earth Sciences Section . 41 Materials Science and Engineering Section . 43 Mathematics and Statistics Section . 46 Physics Section . 49 Division of Science Education . 52 Higher Education Section . 52 K-12 Education Section . 55 Division of Social Sciences . 57 Acknowledgement . 64 2 The following abstracts of oral and poster presentations represent those received by the Abstract Editor. Authors’ affiliations are abbreviated as follows: ACHRI Arkansas Children’s Hospital Research Institute ARS Agriculture Research Services, Little Rock, AR AVMA-PLIT American Veterinary Medical BGSU Bowling Green State University BNL Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY BRCC Baton Rouge Community College CC Centenary College CIT California Institute of Technology CL Corrigan Laboratory, Baton Rouge, LA CTF Cora Texas Manufacturing CU Clemson University DNIRI Delta -

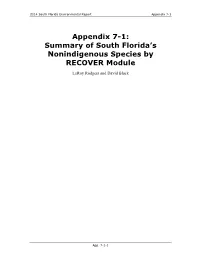

Appendix 7-1: Summary of South Florida's Nonindigenous Species

2014 South Florida Environmental Report Appendix 7-1 Appendix 7-1: Summary of South Florida’s Nonindigenous Species by RECOVER Module LeRoy Rodgers and David Black App. 7-1-1 Appendix 7-1 Volume I: The South Florida Environment Table 1. Summary of South Florida’s nonindigenous animal species and Category I invasive plant species by RECOVER module.1 KY SE GE BC NW NE LO KR Amphibians *Bufo marinus Giant toad x x x x x x x x Eleutherodactylus planirostris Greenhouse frog x x x x x x x x *Osteopilus septentrionallis Cuban treefrog x x x x x x x x Reptiles Agama agama African redhead agama x x x x x Ameiva ameiva Giant ameiva x x Anolis chlorocyanus Hispaniolan green anole x x x Anolis cristatellus cristatellus Puerto Rican crested anole x Anolis cybotes Largehead anole x x x *Anolis distichus Bark anole x x x x x x x *Anolis equestris equestris Knight anole x x x x x x x x Anolis extremus Barbados anole x *Anolis garmani Jamaican giant anole x x x x x Anolis porcatus Cuban green anole x x *Anolis sagrei Brown anole x x x x x x x x Basiliscus vittatus Brown basilisk x x x x x x x *Boa constrictor Common boa x Caiman crocodilus Spectacled caiman x x x Calotes mystaceus Indochinese tree agama x x Table Key KY = Keys NW = Northern Estuaries West Green Found in one module SE = Southern Estuaries NE = Northern Estuaries East Orange Found in all modules GE = Greater Everglades LO = Lake Okeechobee Blue Found in all but one module BC = Big Cypress KR = Kissimmee River Pink Status changed since 2011 *Species that make significant use of less disturbed portions of the module. -

Lovebug Plecia Nearcticahardy (Insecta: Diptera: Bibionidae)1 H

EENY 47 Lovebug Plecia nearcticaHardy (Insecta: Diptera: Bibionidae)1 H. A. Denmark, F. W. Mead, and T. R. Fasulo2 Introduction University of Florida entomologists introduced this species into Florida. However, Buschman (1976) documented the The lovebug, Plecia nearctica Hardy, is a bibionid fly species progressive movement of this fly species around the Gulf that motorists may encounter as a serious nuisance when Coast into Florida. Research was conducted by University traveling in southern states. It was first described by Hardy of Florida and US Department of Agriculture entomologists (1940) from Galveston, Texas. At that time he reported it to only after the lovebug was well established in Florida. be widely spread, but more common in Texas and Louisiana than other Gulf Coast states. Figure 1. Swarm of lovebugs, Plecia nearctica Hardy, on flowers. Credits: James Castner, UF/IFAS Figure 2. Adult lovebugs, Plecia nearctica Hardy, swarm on a building. Credits: Debra Young, used with permission Within Florida, this fly was first collected in 1949 in Escambia County, the westernmost county of the Florida panhandle. Today, it is found throughout Florida. With numerous variations, it is a widely held myth that 1. This document is EENY 47, one of a series of the Entomology and Nematology Department, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date August 1998. Revised April 2015. Reviewed February 2021. Visit the EDIS website at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu for the lastest version of this publication. This document is also available on the Featured Creatures website at http://entnemdept.ifas.ufl.edu/creatures/. 2. H. A. Denmark, courtesy professor; F. -

Ecological Consequences Artificial Night Lighting

Rich Longcore ECOLOGY Advance praise for Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting E c Ecological Consequences “As a kid, I spent many a night under streetlamps looking for toads and bugs, or o l simply watching the bats. The two dozen experts who wrote this text still do. This o of isis aa definitive,definitive, readable,readable, comprehensivecomprehensive reviewreview ofof howhow artificialartificial nightnight lightinglighting affectsaffects g animals and plants. The reader learns about possible and definite effects of i animals and plants. The reader learns about possible and definite effects of c Artificial Night Lighting photopollution, illustrated with important examples of how to mitigate these effects a on species ranging from sea turtles to moths. Each section is introduced by a l delightful vignette that sends you rushing back to your own nighttime adventures, C be they chasing fireflies or grabbing frogs.” o n —JOHN M. MARZLUFF,, DenmanDenman ProfessorProfessor ofof SustainableSustainable ResourceResource Sciences,Sciences, s College of Forest Resources, University of Washington e q “This book is that rare phenomenon, one that provides us with a unique, relevant, and u seminal contribution to our knowledge, examining the physiological, behavioral, e n reproductive, community,community, and other ecological effectseffects of light pollution. It will c enhance our ability to mitigate this ominous envirenvironmentalonmental alteration thrthroughough mormoree e conscious and effective design of the built environment.” -

94: Frank & Mccoy Intro. 1 INTRODUCTION to INSECT

Behavioral Ecology Symposium ’94: Frank & McCoy Intro. 1 INTRODUCTION TO INSECT BEHAVIORAL ECOLOGY : THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE BEAUTIFUL: NON-INDIGENOUS SPECIES IN FLORIDA INVASIVE ADVENTIVE INSECTS AND OTHER ORGANISMS IN FLORIDA. J. H. FRANK1 AND E. D. MCCOY2 1Entomology & Nematology Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611-0620 2Biology Department and Center for Urban Ecology, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620-5150 ABSTRACT An excessive proportion of adventive (= “non-indigenous”) species in a community has been called “biological pollution.” Proportions of adventive species of fishes, am- phibia, reptiles, birds and mammals in southern Florida range from 16% to more than 42%. In Florida as a whole, the proportion of adventive plants is about 26%, but of in- sects is only about 8%. Almost all of the vertebrates were introduced as captive pets, but escaped or were released into the wild, and established breeding populations; few arrived as immigrants (= “of their own volition”). Almost all of the plants also were in- troduced, a few arrived as immigrants (as contaminants of shipments of seeds or other cargoes). In contrast, only 42 insect species (0.3%) were introduced (all for bio- logical control of pests, including weeds). The remainder (about 946 species, or 7.6%) arrived as undocumented immigrants, some of them as fly-ins, but many as contami- nants of cargoes. Most of the major insect pests of agriculture, horticulture, human- made structures, and the environment, arrived as hitchhikers (contaminants of, and stowaways in, cargoes, especially cargoes of plants). No adventive insect species caus- ing problems in Florida was introduced (deliberately) as far as is known. -

Population Ecology of Insect Invasions and Their Management*

ANRV330-EN53-20 ARI 2 November 2007 19:36 Population Ecology of Insect Invasions and Their Management∗ Andrew M. Liebhold and Patrick C. Tobin Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Northern Research Station, Morgantown, West Virginia 26505; email: [email protected], [email protected] Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2008. 53:387–408 Key Words First published online as a Review in Advance on Allee effect, establishment, nonindigenous species, spread, September 17, 2007 stratified dispersal The Annual Review of Entomology is online at ento.annualreviews.org Abstract This article’s doi: During the establishment phase of a biological invasion, popula- 10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091401 by 150.185.73.180 on 05/02/08. For personal use only. tion dynamics are strongly influenced by Allee effects and stochastic Copyright c 2008 by Annual Reviews. dynamics, both of which may lead to extinction of low-density pop- All rights reserved ulations. Allee effects refer to a decline in population growth rate 0066-4170/08/0107-0387$20.00 with a decline in abundance and can arise from various mechanisms. ∗ The U.S. Government has the right to retain a Strategies to eradicate newly established populations should focus Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2008.53:387-408. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org nonexclusive, royalty-free license in and to any on either enhancing Allee effects or suppressing populations below copyright covering this paper. Allee thresholds, such that extinction proceeds without further inter- vention. The spread phase of invasions results from the coupling of population growth with dispersal. Reaction-diffusion is the simplest form of spread, resulting in continuous expansion and asymptotically constant radial rates of spread. -

West Marsh Preserve Wildlife Species List

WMP Wildlife Species List Designated Status Scientific Name Common Name FWC FWS FNAI MAMMALS Order: Xenarthra Family: Dasypodidae (armadillos) Dasypus novemcinctus nine-banded armadillo * G5 Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae (cats) Lynx rufus bobcat G5 Family: Canidae (wolves and foxes) Canis latrans coyote G5 Family: Mustelidae (weasels, otters and relatives) Lutra canadensis northern river otter G5 Family: Procyonidae (raccoons) Procyon lotor raccoon G5/S5 Order: Artiodactyla Family: Suidae (old world swine) Sus scrofa feral hog * G5 Family: Cervidae (deer) Odocoileus virginianus white-tailed deer G5/S5 Order: Rodentia Family: Sciuridae (squirrels and their allies) Sciurus carolinensis eastern gray squirrel G5 Order: Lagomorpha Family: Leporidae (rabbits and hares) Sylvilagus palustris marsh rabbit G5 BIRDS Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae (swans, geese, and ducks) Dendrocygna autumnalis black-bellied whistling duck G5 Cairina moschata muscovy duck G4 Aix sponsa wood duck G5 Spatula discors blue-winged teal G5 Spatula clypeata northern shoveler G5 Mareca strepera gadwall G5 Mareca americana American wigeon G5 Anas platyrhynchos mallard G5 Anas fulvigula mottled duck G4/S3S4 Anas acuta northern pintail G5 Anas crecca green-winged teal G5 Aythya americana redhead G5 Aythya collaris ring-necked duck G5 Aythya affinis lesser scaup G5/S5 Lophodytes cucullatus hooded merganser G5 Mergus serrator red-breasted merganser G5 Oxyura jamaicensis ruddy duck G5 Order: Galliformes Family: Odontophoridae (new world quails) Colinus virginianus northern -

Sue's Pdf Quark Setting

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83488-9 - Insect Ecology: Behavior, Populations and Communities Peter W. Price, Robert F. Denno, Micky D. Eubanks, Deborah L. Finke and Ian Kaplan Index More information AUTHOR INDEX Aanen, D.K., 227 Amman, G.D., 600 Bach, C.E., 152 Abrahamson, W.G., 16, 161, 162, Andersen, A.N., 580 Bacher, 275 165 Andersen, N.M., 401 Bacher, S., 275 Abrams, 274 Anderson, J.M., 114 Bachman, S., 567 Abrams, P.A., 195, 273, 276 Anderson, R.M., 336, 337, 338 Ba¨ckhed, F., 225 Acorn, J., 250 Anderson, R.S., 415 Badenes-Perez, F.R., 400 Adams, D.C., 203 Andersson, M., 82, 83, 87 Baerends, G.P., 29 Adams, E.S., 435 Andow, D.A., 127, 128, 179, 276, 513, Bailey, J.K., 426, 474, 475, 603 Adamson, R.S., 573 528 Bailey, V.A., 279, 356 Addicott, J.F., 242, 507 Andres, M.R., 116, 117, 118 Baker, R.R., 54 Addy, N.D., 574, 601, 602 Andrew, N.R., 566 Baker, I., 247 Adjei-Maafo, I.K., 530 Andrewartha, H.G., 27, 260, 261, 279, Baker, T.C., 53 Adler, L.S., 155 356, 404 Baker, W.L., 166 Adler, P.H., 8 Andrews, J.H., 310 Baldwin, I.T., 121, 122, 125, 126, 127, Agarwal, V.M., 506 Aneshansley, D.J., 48 129, 143, 144, 166, 174, 179, 187, Agnew, P., 369 Anonymous, 18 197, 201, 204, 208, 221, 492, 498 Agrawal, A.A., 99, 108, 114, 118, 121, Anstett, M.-C., 236, 243, 244 Ballabeni, P., 162 122, 125, 126, 128, 129, 130, 133, Antonovics, J., 471 Baltensweiler, 414 136, 139, 156, 161, 197, 204, 205, Aoki, S., 80 Baltensweiler, W., 407, 410, 424 208, 216, 219, 299, 444, 471, 492, Appel, H.M., 124, 128 Bangert, 465, 472 493, 502, 507, 509, 512, 513 -

Evolution and Classification of Bibionidae (Diptera: Bibionomorpha)

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Scott J. Fitzgerald for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology presented on 3 June, 2004. Title: Evolution and Classification of Bibionidae (Diptera: Bibionomorpha). Abstract approved: Signature redacted forprivacy. p 1ff Darlene D. Judd The family Bibionidae has a worldwide distribution and includes approximately 700 species in eight extant genera. Recent studies have not produced compelling evidence supporting Bibionidae as a monophyletic group or identified the sister group to bibionids. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the classification and evolution of the family Bibionidae in a cladistic framework. The study has four primary objectives: 1) test the monophyly of the family; 2) determine the sister group of Bibionidae; 3) examine generic and subfamilial relationships within the family; and 4) provide a taxonomic revision of the extant and fossil genera of Bibionidae. Cladistic methodology was employed and 212 morphological characters were developed from all life stages (adult, pupa, larva, and egg). Characters were coded as binary or multistate and considered equally weighted and unordered. A heuristic search with a multiple random taxon addition sequence was used and Bremer support values are provided to show relative branch support. A strict consensus of 43 equal-length trees of 1,106 steps indicates that the family Bibionidae is monophyletic and is sister group to Pachyneuridae. All bibionid genera are supported as monophyletic except for Bibio and Bibiodes (monophyly of the latter genus was not examined because only one exemplar was included). Results indicate that the subfamilies Hesperininae and Bibioninae are monophyletic and Pleciinae is paraphyletic.