The First Frontier-The Swedes and the Dutch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Melyn Pa Troonship of St1~ Ten Island

THE MELYN PA TROONSHIP OF ST1~ TEN ISLAND .\DDRESS DELI\.ERED .\T THE XIXTH .:\X~CAL :\IEETI:\"G OF THE :\"E\Y YOR~ BRA~CH OF THI◄: ORDER OF COLONIAL LORDS OF MANORS IN AMERICA Held in the City of Ke\v ·York, April 29th, 1921 BY \\.ILLL\:\I CHCRCHILL HOCSTO:\; OF GER:\L\~TO\Y:\;, PHILADELPHIA 1923 Born, 1592. Died, 16i2. Original in the possession of The Kew York Historical Society, reproduced by permission. This 1fonograph is compiled from the following authorities: Brodhead's History of the State of Xew York. New Amsterdam and Its People, J. H. Innes. The Story of Kew Xetherland, \Ym. Elliot Griflis. Saint Nicholas Society Genealogical Record r9r6. Collections of the Xew York Historical Society, r9r3- l\Ielyn Papers. The Van Rensselaer Bo'1.-ier ~fanuscripts. THE PATROONSHIP OF STATEN ISLAND In Brodhead's History of New York it is recorded that in 1630 it was obvious that the rural tenantry of Holland did not possess the requisite means to sustain the expense of emigra tion, and the associate directors of the West India Company thought that the permanent agricultural settlement of their American province could be best accomplished by the organiza tion of separate subordinate colonies or manors under large proprietors. To tempt the ambition of such capitalists, pecu liar privileges were offered to them. These privileges, never theless, were carefully confined to members of the \Vest India Company. The Charter provided that any such members as should, within four years, plant a colony of fifty adults in any part of New Netherland except the reserved ic;land of l\!Ianhattan, should be acknowledged as a Patroon, or feudal Chief of the territory he might thus colonize. -

UC Berkeley Charlene Conrad Liebau Library Prize for Undergraduate Research

UC Berkeley Charlene Conrad Liebau Library Prize for Undergraduate Research Title The Omnipotent Beaver in Van der Donck's A Description of New Netherland: A Natural Symbol of Promise in the New World Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/870174nb Author van den Hout, Julie Publication Date 2015-04-01 Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE OMNIPOTENT BEAVER IN VAN DER DONCK’S A DESCRIPTION OF NEW NETHERLAND A Natural Symbol of Promise in the New WorlD Julie van den Hout Dutch H196: Honors Studies in Dutch Faculty Adviser: Jeroen Dewulf University of California, Berkeley Spring, 2015 1 INTRODUCTION In May of 1653, Adriaen van Der Donck submitteD his book, A Description of New Netherland, to the Directors of the West InDia Company (WIC) at the Chamber in AmsterDam for approval, in advance of requesting a copyright from the States General of the Dutch Republic.1 This seemeD like gooD Politics considering Van der Donck had reapeD the wrath of the West InDia Company Directors a few years earlier when he, as a colonial delegate, formally complaineD in his Remonstrance of New Netherland to the States General about the West InDia Company’s management of the colony. Both the West InDia Company and the States General approveD of Van der Donck’s proposed book; he was granteD a fifteen-year copyright.2 A Description of New Netherland, originally published in 1655, is DiviDeD into four main chaPters. The first chapter, “The Country,” discusses Dutch rights to the territory and the physical aspects of the country, detailing land anD waterways as well as local flora and fauna. -

History and Genealogy of the Vreeland Family

.0^ . ^ovV : ^^^* • .rC^^'^.t.'^ . O .V . 4:^ "^^ o.* "^ v° *^' %- 'd- m^ ^^^ \ a/ "O* - '^^ .^'-^ "<*>. n"^ ,o«<.- -^^ ^ Vol •.°' ^^ aO ^ './ >:^^:- >. aV .^j^^^. Nicholas Garretson \'reeland. THHR BOOK: Wriltenarranged ^adaptgd BY ON E OF THEM WWW OIMT^oN VREELSIND Title parte and ofcher* di-awing/s by FR.flNCI5 WILLIAM Vl^EELflND^ Printed by CHflUNCELY H O L T- NOa7V^NDEPy%'" 3TIIEE.T • NEW YORK: HISTORY GENEALOGY of the VREELAND FAMILY Edited by NICHOLAS GARRETSON VREELAND HISTORICAL PUBLISHING CO. Jersey City, Nert) Jersey MDCCCCIX sT 1'^ \(\ •2> (At Copyright 1909 BY Nicholas G. Vrekland Cla.A,a3<* 112 JUL 28 1909 1 : table:contentsof CHAPTER. TITLE. PAGE. Foreword. 9 Preface. 10 PART FIRST — THE STORY OF HOLLAND. 1 In Day.s of Caesar 17 2 Fifteen Centuries of Struggle 20 3 The Dutch take Holland 21 4 Chaos leads to System 23 5 Dutch War Songs 24 Beggars of the Sea 24 Moeder Holland 29 Oranje Boven 30 6 Independence at Last 31 7 Holland and its People 33 8 Holland of To-day 41 PART SECOND — THE STORY OF AMERICA. 9 The American Birthright (Poem)... 49 10 In the New World, 1609-38 53 1 On Communipaw's Shore, 1646 57 12 Settlement of Bergen, 1660 59 13 Religion and Education 61 14 Battledore and Shuttlecock, 1664-74 63 15 Paulus Hook, 1800 66 16 From Youth to Manhood, 1840- 1909 69 17 Manners and Customs 73 18 Nomenclature 76 19 The True Dutch Influence 83 20 Land Titles 90 PART THIRD — THE STORY OF THE VREELANDS. 2 An Old Vreeland Family 99 22 The Town Vreeland, in Holland 104 CONTENTS—Continued. -

Dutch Influences on Law and Governance in New York

DUTCH INFLUENCES 12/12/2018 10:05 AM ARTICLES DUTCH INFLUENCES ON LAW AND GOVERNANCE IN NEW YORK *Albert Rosenblatt When we talk about Dutch influences on New York we might begin with a threshold question: What brought the Dutch here and how did those beginnings transform a wilderness into the greatest commercial center in the world? It began with spices and beaver skins. This is not about what kind of seasoning goes into a great soup, or about European wearing apparel. But spices and beaver hats are a good starting point when we consider how and why settlers came to New York—or more accurately—New Netherland and New Amsterdam.1 They came, about four hundred years ago, and it was the Dutch who brought European culture here.2 I would like to spend some time on these origins and their influence upon us in law and culture. In the 17th century, several European powers, among them England, Spain, and the Netherlands, were competing for commercial markets, including the far-east.3 From New York’s perspective, the pivotal event was Henry Hudson’s voyage, when he sailed from Holland on the Halve Maen, and eventually encountered the river that now bears his name.4 Hudson did not plan to come here.5 He was hired by the Dutch * Hon. Albert Rosenblatt, former Judge of the New York Court of Appeals, is currently teaching at NYU School of Law. 1 See COREY SANDLER, HENRY HUDSON: DREAMS AND OBSESSION 18–19 (2007); ADRIAEN VAN DER DONCK, A DESCRIPTION OF NEW NETHERLAND 140 (Charles T. -

The Worlds of the Seventeenth-Century Hudson Valley

1 The Seventeenth-Century Empire of the Dutch Republic, c. 1590–1672 Jaap Jacobs he overseas expansion of the Dutch Republic, culminating in the “First Dutch Empire,” is a remarkable story of the quick rise to prominence of a small country in northwestern Europe. Much smaller Tin population than European rivals like Spain, England, and France, and without considerable natural resources, the Republic was able within a few decades to lay the foundation for a colonial empire of which remnants are still part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands nowadays. This First Dutch Empire, running roughly from the beginning of the seventeenth century until the early 1670s, was characterized by rapid expansion, both in the Atlantic area and in Asia. The phase that followed, the Second Dutch Empire, shows a divergence in development between the East and West. In the East, ter- ritorial expansion—often limited to trading posts, not settlement colonies— continued and trade volume increased, but in the Western theater the Dutch witnessed a contraction of territorial possessions, especially with the loss of New Netherland and Dutch Brazil. Even so, Dutch trade and shipping in the Atlantic was not solely dependent upon colonial footholds, not in the least because the Dutch began to participate in the Atlantic slave trade. This Second Dutch Empire ended in the Age of Democratic Revolutions, when upheavals in Europe and America brought an end to both the Dutch East and West India Companies and led to the loss of a number of colonies, such as South Africa, Sri Lanka, and Essequibo and Demerara on the Guyana coast. -

Peter Minuit Story

ONE A NEW LAND By ten and twenties the settlers came in 1624 and 1625, pitching on the inhuman waves in frightfully vulnerable vessels. Two months it took to follow in the wake of the English explorer Henry Hudson, three if the winds failed. Hudson had sailed, in 1609, on behalf of the Dutch East India Company, so the Dutch claimed the territory and named their colony New Netherland. The Dutch provinces were the melting pot of Europe, and the settlers were themselves a mix of peoples. The colony stretched across a huge swath of North America, covering all or part of five future states: New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania and Delaware. The ships arrived at what would later be New York Harbor. “We were much gratified on arriving in this country,” one settler wrote home. “Here we found beautiful rivers, bubbling fountains flowing down into the valleys ...” TWO PETER MINUIT He had grown up speaking German, but his ancestry was French, so his name was pronounced in the French way - Min-wee. He had no military training, but he was an individualistic, take-charge sort who would alter the course of history by sheer force of will. Peter Minuit married and settled in the Dutch city of Utrecht, but then, learning of a venture to the New World, went to Amsterdam in 1624 and asked the West India Company for a posting to New Netherland. He shipped out with one of the first groups of settlers. The director must have been impressed by his wits and energy, for the company ordered the colony’s leader, Willem Verhulst, that “He shall have Peter Minuyt .. -

Washington Irving's Use of Historical Sources in the Knickerbocker History of New York

WASHINGTON IRVING’S USE OF HISTORICAL SOURCES IN THE KNICKERBOCKER. HISTORY OF NEW YORK Thesis for the Degree of M. A. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY DONNA ROSE CASELLA KERN 1977 IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII 3129301591 2649 WASHINGTON IRVING'S USE OF HISTORICAL SOURCES IN THE KNICKERBOCKER HISTORY OF NEW YORK By Donna Rose Casella Kern A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English 1977 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . CHAPTER I A Survey of Criticism . CHAPTER II Inspiration and Initial Sources . 15 CHAPTER III Irving's Major Sources William Smith Jr. 22 CHAPTER IV Two Valuable Sources: Charlevoix and Hazard . 33 CHAPTER V Other Sources 0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 Al CONCLUSION 0 O C O O O O O O O O O O O 0 O O O O O 0 53 APPENDIX A Samuel Mitchell's A Pigture 9: New York and Washington Irving's The Knickerbocker Histgrx of New York 0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o c o o o o 0 56 APPENDIX B The Legend of St. Nicholas . 58 APPENDIX C The Controversial Dates . 61 APPENDIX D The B00k'S Topical Satire 0 o o o o o o o o o o 0 6A APPENDIX E Hell Gate 0 0.0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 66 APPENDIX F Some Minor Sources . -

The 1693 Census of the Swedes on the Delaware

THE 1693 CENSUS OF THE SWEDES ON THE DELAWARE Family Histories of the Swedish Lutheran Church Members Residing in Pennsylvania, Delaware, West New Jersey & Cecil County, Md. 1638-1693 PETER STEBBINS CRAIG, J.D. Fellow, American Society of Genealogists Cartography by Sheila Waters Foreword by C. A. Weslager Studies in Swedish American Genealogy 3 SAG Publications Winter Park, Florida 1993 Copyright 0 1993 by Peter Stebbins Craig, 3406 Macomb Steet, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016 Published by SAG Publications, P.O. Box 2186, Winter Park, Florida 32790 Produced with the support of the Swedish Colonial Society, Philadelphia, Pa., and the Delaware Swedish Colonial Society, Wilmington, Del. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 92-82858 ISBN Number: 0-9616105-1-4 CONTENTS Foreword by Dr. C. A. Weslager vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The 1693 Census 15 Chapter 2: The Wicaco Congregation 25 Chapter 3: The Wicaco Congregation - Continued 45 Chapter 4: The Wicaco Congregation - Concluded 65 Chapter 5: The Crane Hook Congregation 89 Chapter 6: The Crane Hook Congregation - Continued 109 Chapter 7: The Crane Hook Congregation - Concluded 135 Appendix: Letters to Sweden, 1693 159 Abbreviations for Commonly Used References 165 Bibliography 167 Index of Place Names 175 Index of Personal Names 18 1 MAPS 1693 Service Area of the Swedish Log Church at Wicaco 1693 Service Area of the Swedish Log Church at Crane Hook Foreword Peter Craig did not make his living, or support his four children, during a career of teaching, preparing classroom lectures, or burning the midnight oil to grade examination papers. -

Council Minutes 1655-1656

Council Minutes 1655-1656 New Netherland Documents Series Volume VI ^:OVA.BUfi I C ^ u e W « ^ [ Adriaen van der Donck’s Map of New Netherland, 1656 Courtesy of the New York State Library; photo by Dietrich C. Gehring Council Minutes 1655-1656 ❖ Translated and Edited by CHARLES T. GEHRING SJQJ SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright © 1995 by The Holland Society of New York ALL RIGHTS RESERVED First Edition, 1995 95 96 97 98 99 6 5 4 3 21 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements o f American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.48-1984.@™ Produced with the support of The Holland Society o f New York and the New Netherland Project of the New York State Library The preparation of this volume was made possibl&in part by a grant from the Division of Research Programs of the National Endowment for the Humanities, an independent federal agency. This book is published with the assistance o f a grant from the John Ben Snow Foundation. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data New Netherland. Council. Council minutes, 1655-1656 / translated and edited by Charles T. Gehring. — lsted. p. cm. — (New Netherland documents series ; vol. 6) Includes index. ISBN 0-8156-2646-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. New York (State)— Politics and government—To 1775— Sources. 2. New York (State)— History—Colonial period, ca. 1600-1775— Sources. 3. New York (State)— Genealogy. 4. Dutch—New York (State)— History— 17th century—Sources. 5. Dutch Americans—New York (State)— Genealogy. -

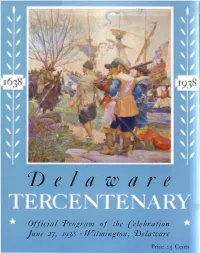

Delaware Tercentenary Program

Vela ware Official Program., of the Celebration June 27, I9J8 ·Wilmington, 'Delaware Price 25 Cents FORT CHRISTINA H.M. CHRISTINA, Queen of Sweden (r6J'l-l 654) during H.M. GusTAvus A oo LPH U s , King of Sweden (161 '· whose reign New Sweden was founded. I 632) through whose support New Sweden becan1e a possibility. l DEcEMBER 1637, the Swedish Expedi tion, under Peter Minuit, sailed from Sweden in the ship, "Kalmar Nyckel" and the yacht,"Fogel Grip," and finally reached the "Rocks" in March r6J8. Here Minui t made a treaty with the Indians and, with a salute of two cannons, claimed for Sweden all that land from the Christina River down to Bombay Hook. Wt�forl(g� ?t�dfantt� �fnur }llttttbetaCONTRACTET gnga(n�cat�ct S�bre �mpagnict �tbf J(onuugart;rctj ewcrfg�c. 6rdlc iam·om �it�dm &\jffdin�. £)�uu 4/ft6tt 9?tl)trfdnb(rc �prdfct �fau p.S6�Mnfl.al 2ft' ~ £ BEGINNINGS of the establishment of New }:RICO SCHRODERO. L S~eden rnay be traced back to the efforts of one William Usselinx, a native of Antwerp, who interested King Gustavus Adolphus in the enter prise. At the right is reproduced the cover of the contract and prospectus which was used to interest The Cover investors in the venture. Here is reproduced the famous painting by Stanley M. Arthurs, Esq., ofthe landing ofthe .firstSwedish expedi tion at the "Roclcs." The painting is owned by Joseph S. Wilson, Esq. GusTAF V ' K.lng • of S weden , d u r .1 n g . w h ose reign, In I9J8 , t h e ter- centenary of · the found·lng of N ew Sweden IS celebrated. -

The Dutch, Munsees, and the Purchase of Manhattan Island Paul Otto George Fox University, [email protected]

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of History, Department of History, Politics, and International Politics, and International Studies Studies 1-2015 The Dutch, Munsees, and the Purchase of Manhattan Island Paul Otto George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/hist_fac Part of the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation Published by New York State Bar Association Journal 87(1), January 2015, pp.10-17 (reprint of “Real Estate or Political Sovereignty”) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History, Politics, and International Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of History, Politics, and International Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Dutch, Munsees, and the Purchase of Manhattan Island by Paul Otto from Opening Statements – Law, Jurisprudence, and the History of Dutch New York Albert M. Rosenblatt and Julia C. Rosenblatt, Eds. From the Introduction to Opening Statements nerve center. For that near half-century, the Dutch estab- We may call England our “mother country,” but our lished government, trade, and institutions that helped culture, political system, and jurisprudence have a more shape the future of what would become New York. varied heritage. Each state with its own settlement his- For years, the history of New York under Dutch rule tory has a unique flavor. Our nation’s lineage, and New languished in what Washington Irving called “the regions York’s in particular, has an often-overlooked Dutch of doubt and fable.” He used this phrase in his preface, component. -

Thinking Geographically: Wilmington’S Riverfront Over Time

Delaware Recommended Curriculum This unit has been created as an exemplary model for teachers in (re)design of course curricula. An exemplary model unit has undergone a rigorous peer review and jurying process to ensure alignment to selected Delaware Content Standards. Unit Title: Thinking Geographically: Wilmington’s Riverfront over Time Designed by: Kristin Becker, Red Clay Consolidated School District Sam Heed, Kalmar Nyckel Foundation Support provided by Kalmar Nyckel Foundation, Riverfront Development Corporation of Delaware, Swedish Council of America, and Finlandia Foundation National Special thanks to Maggie Legates, Delaware Geographic Alliance Images provided by BrightFields, Inc., Delaware Public Archives, and the RDC Content Area: Social Studies Grade Level: 5 ________________________________________________________________________ Summary of Unit Cultural differences produce patterns of diversity in language, religion, economic activity, social custom, and political organization across the Earth's surface. Places reflect the culture of the inhabitants as well as the ways that culture has changed over time. Places also reflect the connections and flow of information, goods, and ideas with other places. Students who will live in an increasingly interconnected world need an understanding of the processes that produce distinctive places and how those places change over time. Students need to learn to apply the ideas of site and situation to explain the nature of particular places. Site choices at different time periods help explain the distribution of places in Delaware. The earliest European settlements such as Lewes, New Castle, Dover, Odessa, and Seaford were at the head of navigable rivers and streams that flowed into the Delaware River or Chesapeake Bay. Soils were fertile (site) and locations gave easy transport access to markets (situation).