Report Identification Mission ADNA, 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk Assessment: Asset Identification & Characterization

This Working Draft Submittal is a preliminary draft document and is not to be used as the basis for final design, construction or remedial action, or as a basis for major capital decisions. Please be advised that this document and associated deliverables have not undergone internal reviews by URS. SECTION 3b - RISK ASSESSMENT: ASSET IDENTIFICATION & CHARACTERIZATION SECTION 3b - RISK ASSESSMENT: IDENTIFICATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF ASSETS Overview An inventory of geo-referenced assets in Rensselaer County has been created in order to identify and characterize property and persons potentially at risk from the identified hazards. Understanding the type and number of hazards that exist in relation to known hazard areas is an important step in the process of formulating the risk assessment and quantifying the vulnerability of the municipalities that make up Rensselaer County. For this plan, six key categories of assets have been mapped and analyzed using GIS data provided by Rensselaer County, with some additional data drawn from other public sources: 1. Improved property: This category includes all developed properties according to parcel data provided by Rensselaer County and equalization rates from the New York State Office of Real Property Services. Impacts to improved properties are presented as a percentage of each community’s total value of improvements that may be exposed to the identified hazards. 2. Emergency facilities: This category covers all facilities dedicated to the management and response of emergency or disaster situations, and includes emergency operations centers (EOCs), fire stations, police stations, ambulance stations, shelters, and hospitals. Impacts to these assets are presented by tabulating the number of each type of facility present in areas that may be exposed to the identified hazards. -

THE BULLETIN Number 69 March 1977

THE BULLETIN Number 69 March 1977 CONTENTS Archaeology of the New York Metropolis Robert L. Schuyler 1 Archeological Investigations in the Vicinity of "Fort Crailo" During Sewer Line Construction Under Riverside Avenue in Rensselaer, New York Paul R. Huey, Lois M. Feister and Joseph E. McEvoy 19 Archaeology, Education and the Indian Castle Church Wayne Lenig 42 New York State Archaeological Association-Minutes of the 60th Annual Meeting 52 No. 69, March 1977 1 ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE NEW YORK METROPOLIS Robert L. Schuyler City College, CUNY Introduction Almost ten thousand years of human prehistory are buried in the shores, peninsulas, and islands on which New York City and its satellite communities stand today.1 Between 14,000 B. C. and 10, 000 B. C. the final retreat of the Wisconsin ice sheet modified and opened the harbor area. Human population was then able to enter the estuary and lower valley of the Hudson by following two natural migration corridors. Movement east and west was possible along the coastal plain, while access to the interior followed the river and its valley that ran over 200 miles to the north. Once Man entered the region he settled in. Bands of Paleo-Indian hunter-gatherers and their archaic descendants found an area rich in natural resources. A complex interfacing of salt and fresh water provided marine, estuarine, and riparian sources of food. On land an even broader transition between three major physiographic provinces-New England Upland (Manhattan and Westchester County), New Jersey Lowland, and Atlantic Coastal Plain (Staten Island and Long Island)-greatly enriched the range and variety of available fauna and flora. -

Research Bibliography on the Industrial History of the Hudson-Mohawk Region

Research Bibliography on the Industrial History of the Hudson-Mohawk Region by Sloane D. Bullough and John D. Bullough 1. CURRENT INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGY Anonymous. Watervliet Arsenal Sesquicentennial, 1813-1963: Arms for the Nation's Fighting Men. Watervliet: U.S. Army, 1963. • Describes the history and the operations of the U.S. Army's Watervliet Arsenal. Anonymous. "Energy recovery." Civil Engineering (American Society of Civil Engineers) 54 (July 1984): 60- 61. • Describes efforts of the City of Albany to recycle and burn refuse for energy use. Anonymous. "Tap Industrial Technology to Control Commercial Air Conditioning." Power 132 (May 1988): 91–92. • The heating, ventilation and air–conditioning (HVAC) system at the Empire State Plaza in Albany is described. Anonymous. "Albany Scientist Receives Patent on Oscillatory Anemometer." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 70 (March 1989): 309. • Describes a device developed in Albany to measure wind speed. Anonymous. "Wireless Operation Launches in New York Tri- Cities." Broadcasting 116 10 (6 March 1989): 63. • Describes an effort by Capital Wireless Corporation to provide wireless premium television service in the Albany–Troy region. Anonymous. "FAA Reviews New Plan to Privatize Albany County Airport Operations." Aviation Week & Space Technology 132 (8 January 1990): 55. • Describes privatization efforts for the Albany's airport. Anonymous. "Albany International: A Century of Service." PIMA Magazine 74 (December 1992): 48. • The manufacture and preparation of paper and felt at Albany International is described. Anonymous. "Life Kills." Discover 17 (November 1996): 24- 25. • Research at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy on the human circulation system is described. Anonymous. "Monitoring and Data Collection Improved by Videographic Recorder." Water/Engineering & Management 142 (November 1995): 12. -

Why the Dutch? the Historical Context of New Netherland

1 Why the Dutch? The Historical Context of New Netherland Charles T. Gehring The past is elusive. No matter how hard we try to imagine what the world was like centuries ago, the attempt conjures up only blurry images, which slip away like a dream. However, we do have tools available to sharpen these images of the past: primary source materials and archaeological evi- dence. With both we can attempt to construct a world in which we never lived. If we have any advantage at all, it’s only that we know what that past world’s future will be like.proof The goal of this book is to provide the latest archaeology of the area that the Dutch once called Nieuw Nederlandt. As an increasing number of translations of the records of this West India Company (WIC) endeavor become available to researchers, it is hoped that this collection of articles will enhance the words that the Dutch left behind. It’s fitting that we review why the Dutch were here in the first place. Most of the narrative facts of the Dutch story are well known and ac- cepted among historians who specialize in the history of the Dutch Repub- lic and its colonial undertakings. Accordingly, I use citations here spar- ingly; however, the reader wishing a deeper understanding should consult the sources cited at the end of this chapter. In the seventeenth century, the Dutch possessions lay between the New England colonies to the northeast and the tobacco colonies of Maryland and Virginia to the southwest. In 1614 the region appeared in a document of the States General of the United Provinces of the Netherlands as New Netherland. -

Washington Irving's Use of Historical Sources in the Knickerbocker History of New York

WASHINGTON IRVING’S USE OF HISTORICAL SOURCES IN THE KNICKERBOCKER. HISTORY OF NEW YORK Thesis for the Degree of M. A. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY DONNA ROSE CASELLA KERN 1977 IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII 3129301591 2649 WASHINGTON IRVING'S USE OF HISTORICAL SOURCES IN THE KNICKERBOCKER HISTORY OF NEW YORK By Donna Rose Casella Kern A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English 1977 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . CHAPTER I A Survey of Criticism . CHAPTER II Inspiration and Initial Sources . 15 CHAPTER III Irving's Major Sources William Smith Jr. 22 CHAPTER IV Two Valuable Sources: Charlevoix and Hazard . 33 CHAPTER V Other Sources 0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 Al CONCLUSION 0 O C O O O O O O O O O O O 0 O O O O O 0 53 APPENDIX A Samuel Mitchell's A Pigture 9: New York and Washington Irving's The Knickerbocker Histgrx of New York 0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o c o o o o 0 56 APPENDIX B The Legend of St. Nicholas . 58 APPENDIX C The Controversial Dates . 61 APPENDIX D The B00k'S Topical Satire 0 o o o o o o o o o o 0 6A APPENDIX E Hell Gate 0 0.0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 66 APPENDIX F Some Minor Sources . -

NATURAL LANDS TRUST AGENDA NATURAL LANDS TRUST MEETING October 3, 2014 Location: Office of Natural Lands Management 501 E

New Jersey NATURAL LANDS TRUST AGENDA NATURAL LANDS TRUST MEETING October 3, 2014 Location: Office of Natural Lands Management 501 E. State Street, 5 Station Plaza, 4th Floor Trenton, NJ 12:00 PM I. Statement of Open Public Meetings Act II. General Public Comment III. Financial Report -First and Second Quarter 2014 Financial Reports, for decision IV. Minutes of March 28, 2014 meeting, for decision V. Unfinished Business -Petty’s Island, Pennsauken Township, Camden County, status update including renewal of educational programming contract with New Jersey Audubon Society -Delaware Bay Migratory Shorebird Fund Subcommittee Report (no enclosure) VI. New Business -Delaware Bay Migratory Shorebird Project 2015 Budget Request by Endangered and Nongame Species Program, for decision (no enclosure, budget to be provided at meeting) -Paulinskill River Greenway Conservation Easement Management Fund Expenditure, Andover, Hampton, Lafayette and Newton, Sussex County, for decision -Endangered and Nongame Species Program Memorandum of Understanding, for decision -Office of Natural Lands Management Memorandum of Understanding, for decision -Revisions to Guidelines for Conveyance of Land, for decision -Burlington Island-Burlington City/GA Land Management Assignment Offer, Burlington City, Burlington County, for decision -Final 2013 Annual Report, http://njnlt.org/reports.htm, for discussion (no enclosure) VII. Adjourn Minutes, New Jersey Natural Lands Trust Meeting March 28, 2014 – Page 1 MINUTES OF THE NATURAL LANDS TRUST MEETING March 28, 2014 12:00 PM Office of Natural Lands Management, Trenton, New Jersey Chairman Catania called the meeting to order at 12:11 PM and roll was taken. A quorum of trustees was present. At least one of the trustees was a state governmental representative. -

The 1693 Census of the Swedes on the Delaware

THE 1693 CENSUS OF THE SWEDES ON THE DELAWARE Family Histories of the Swedish Lutheran Church Members Residing in Pennsylvania, Delaware, West New Jersey & Cecil County, Md. 1638-1693 PETER STEBBINS CRAIG, J.D. Fellow, American Society of Genealogists Cartography by Sheila Waters Foreword by C. A. Weslager Studies in Swedish American Genealogy 3 SAG Publications Winter Park, Florida 1993 Copyright 0 1993 by Peter Stebbins Craig, 3406 Macomb Steet, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016 Published by SAG Publications, P.O. Box 2186, Winter Park, Florida 32790 Produced with the support of the Swedish Colonial Society, Philadelphia, Pa., and the Delaware Swedish Colonial Society, Wilmington, Del. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 92-82858 ISBN Number: 0-9616105-1-4 CONTENTS Foreword by Dr. C. A. Weslager vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The 1693 Census 15 Chapter 2: The Wicaco Congregation 25 Chapter 3: The Wicaco Congregation - Continued 45 Chapter 4: The Wicaco Congregation - Concluded 65 Chapter 5: The Crane Hook Congregation 89 Chapter 6: The Crane Hook Congregation - Continued 109 Chapter 7: The Crane Hook Congregation - Concluded 135 Appendix: Letters to Sweden, 1693 159 Abbreviations for Commonly Used References 165 Bibliography 167 Index of Place Names 175 Index of Personal Names 18 1 MAPS 1693 Service Area of the Swedish Log Church at Wicaco 1693 Service Area of the Swedish Log Church at Crane Hook Foreword Peter Craig did not make his living, or support his four children, during a career of teaching, preparing classroom lectures, or burning the midnight oil to grade examination papers. -

Vanderpoel-Verplanck-Vigne

Chapter XI: VanderPoel-Verplanck-Vigne Last Revised: December 4, 2013 We resume our study of the Vanderpool family with the parents of our Wynant van der Poel (as it was still being spelled at this time). They were MELGERT 1 WYNANTSE VAN DER POEL and ARIAANTJE {VERPLANCK} VAN DER POEL , who were married on December 4, 1668. 2 Some Vanderpool family sources say that both Melgert and Ariaantje were born or baptized (Melgert in Fort Orange/Rensselaerswyck) on the same day, December 2, 1646. This date and place cannot be incorrect for Melgert, however, principally because his parents were still living in Amsterdam as late as December 1652. In addition, Melgert had already been born by 1646, for baptismal records in Amsterdam suggest his birth occurred in late 1643: Melgert's parents had two males baptized as Melgerts or Melchert, one in the New Church on August 9, 1641, and another in the Old Church on November 26, 1643. 3 The Melgert who married Ariaantje and fathered Wynant was almost certainly the latter child, who, in accordance with the custom then, was given the same name as his recently deceased older brother. 1 Sometimes this name was spelled Melchert. 2 By coincidence, the parents of both Wynant van der Poel and Catharina de Hooges were married on the same date seven years apart: December 4, 1668. 3 Both churches still exist. As we have seen in the previous chapter, the Old Church also figures in the Bradt portion of this family history. The New Church ( Nieuw Kerk in Dutch), technically called St. -

Council Minutes 1655-1656

Council Minutes 1655-1656 New Netherland Documents Series Volume VI ^:OVA.BUfi I C ^ u e W « ^ [ Adriaen van der Donck’s Map of New Netherland, 1656 Courtesy of the New York State Library; photo by Dietrich C. Gehring Council Minutes 1655-1656 ❖ Translated and Edited by CHARLES T. GEHRING SJQJ SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright © 1995 by The Holland Society of New York ALL RIGHTS RESERVED First Edition, 1995 95 96 97 98 99 6 5 4 3 21 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements o f American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.48-1984.@™ Produced with the support of The Holland Society o f New York and the New Netherland Project of the New York State Library The preparation of this volume was made possibl&in part by a grant from the Division of Research Programs of the National Endowment for the Humanities, an independent federal agency. This book is published with the assistance o f a grant from the John Ben Snow Foundation. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data New Netherland. Council. Council minutes, 1655-1656 / translated and edited by Charles T. Gehring. — lsted. p. cm. — (New Netherland documents series ; vol. 6) Includes index. ISBN 0-8156-2646-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. New York (State)— Politics and government—To 1775— Sources. 2. New York (State)— History—Colonial period, ca. 1600-1775— Sources. 3. New York (State)— Genealogy. 4. Dutch—New York (State)— History— 17th century—Sources. 5. Dutch Americans—New York (State)— Genealogy. -

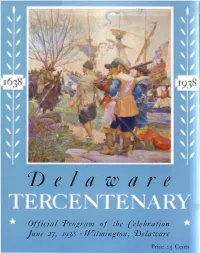

Delaware Tercentenary Program

Vela ware Official Program., of the Celebration June 27, I9J8 ·Wilmington, 'Delaware Price 25 Cents FORT CHRISTINA H.M. CHRISTINA, Queen of Sweden (r6J'l-l 654) during H.M. GusTAvus A oo LPH U s , King of Sweden (161 '· whose reign New Sweden was founded. I 632) through whose support New Sweden becan1e a possibility. l DEcEMBER 1637, the Swedish Expedi tion, under Peter Minuit, sailed from Sweden in the ship, "Kalmar Nyckel" and the yacht,"Fogel Grip," and finally reached the "Rocks" in March r6J8. Here Minui t made a treaty with the Indians and, with a salute of two cannons, claimed for Sweden all that land from the Christina River down to Bombay Hook. Wt�forl(g� ?t�dfantt� �fnur }llttttbetaCONTRACTET gnga(n�cat�ct S�bre �mpagnict �tbf J(onuugart;rctj ewcrfg�c. 6rdlc iam·om �it�dm &\jffdin�. £)�uu 4/ft6tt 9?tl)trfdnb(rc �prdfct �fau p.S6�Mnfl.al 2ft' ~ £ BEGINNINGS of the establishment of New }:RICO SCHRODERO. L S~eden rnay be traced back to the efforts of one William Usselinx, a native of Antwerp, who interested King Gustavus Adolphus in the enter prise. At the right is reproduced the cover of the contract and prospectus which was used to interest The Cover investors in the venture. Here is reproduced the famous painting by Stanley M. Arthurs, Esq., ofthe landing ofthe .firstSwedish expedi tion at the "Roclcs." The painting is owned by Joseph S. Wilson, Esq. GusTAF V ' K.lng • of S weden , d u r .1 n g . w h ose reign, In I9J8 , t h e ter- centenary of · the found·lng of N ew Sweden IS celebrated. -

THE BURCHAM FARM at MILLVILLE, NEW JERSEY by Patricia Bovers

THE BURCHAM FARM AT MILLVILLE, NEW JERSEY By Patricia Bovers Ball December 1995 Table of Contents Introduction Chapter One -- History of Maurice River Area Section One History Early History and Settlement Location and Description First Settlers Europeans in South Jersey The Early History of Maurice River Township Early Surveys of the Maurice River Area John Hopman Section Two --- Woodcutting Lumbering on the Maurice The White Cedar Industry Section Three -- Industry and the Maurice Iron Glass Factories Millville’s Heyday Agriculture Chapter Two -- Marshland Section One -- Early Uses Salt marsh in Colonial New Jersey Cattle in the Marsh Salt Hay Harvesting Section Two --Technology of Salt marsh Location and description Types of Salt marsh: Low, Middle and High Marsh The development of salt marsh i Dyking the marsh: What is dyking? How do dikes work? Building a Dike Diking Tools Marsh Cedar: Mining and Shingle Cutting Section Three -- Administering the banks The History of Diking Diking Laws Corporate Diking Meadow Company Organization Responsibilities of Officers The Nineteenth Section Four -- Burcham area Meadow Companies Millville Meadow Banking Company Heirs of Learning Meadow Company Chapter Three -- Swedes on Delaware Section One --The fight for the Delaware valley New Sweden English Puritans in Salem The English The Long Finn Rebellion New Jersey John Fenwick Section Two First Swedish colonists Johan Printz Section Three -- Life in New Sweden Necessities: Housing Food, Clothing Agriculture: Livestock, Lumbering, Dykes in Raccoon ii -

America the Beautiful Part 1

America the Beautiful Part 1 Charlene Notgrass 1 America the Beautiful Part 1 by Charlene Notgrass ISBN 978-1-60999-141-8 Copyright © 2021 Notgrass History. All rights reserved. All product names, brands, and other trademarks mentioned or pictured in this book are used for educational purposes only. No association with or endorsement by the owners of the trademarks is intended. Each trademark remains the property of its respective owner. Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are taken from the New American Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by the Lockman Foundation. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Cover Images: Jordan Pond, Maine, background by Dave Ashworth / Shutterstock.com; Deer’s Hair by George Catlin / Smithsonian American Art Museum; Young Girl and Dog by Percy Moran / Smithsonian American Art Museum; William Lee from George Washington and William Lee by John Trumbull / Metropolitan Museum of Art. Back Cover Author Photo: Professional Portraits by Kevin Wimpy The image on the preceding page is of Denali in Denali National Park. No part of this material may be reproduced without permission from the publisher. You may not photocopy this book. If you need additional copies for children in your family or for students in your group or classroom, contact Notgrass History to order them. Printed in the United States of America. Notgrass History Gainesboro, TN 1-800-211-8793 notgrass.com Tennessee America the Beautiful Part 1 Introduction Dear Student .....................................................................................................................................vii