Q Research Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volta-Hycos Project

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANISATION Weather • Climate • Water VOLTA-HYCOS PROJECT SUB-COMPONENT OF THE AOC-HYCOS PROJECT PROJECT DOCUMENT SEPTEMBER 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………………………….v 1 WORLD HYDROLOGICAL CYCLE OBSERVING SYSTEM (WHYCOS)……………1 2. BACKGROUNG TO DEVELOPMENT OF VOLTA-HYCOS…………………………... 3 2.1 AOC-HYCOS PILOT PROJECT............................................................................................... 3 2.2 OBJECTIVES OF AOC HYCOS PROJECT ................................................................................ 3 2.2.1 General objective........................................................................................................................ 3 2.2.2 Immediate objectives .................................................................................................................. 3 2.3 LESSONS LEARNT IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AOC-HYCOS BASED ON LARGE BASINS......... 4 3. THE VOLTA BASIN FRAMEWORK……………………………………………………... 7 3.1 GEOGRAPHICAL ASPECTS....................................................................................................... 7 3.2 COUNTRIES OF THE VOLTA BASIN ......................................................................................... 8 3.3 RAINFALL............................................................................................................................. 10 3.4 POPULATION DISTRIBUTION IN THE VOLTA BASIN.............................................................. 11 3.5 SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS........................................................................................... -

Région Du GONTOUGO

RAPPORT DE SYNTHESE DU CONTROLE INOPINÉ DE LA QUALITÉ DE SERVICE (QoS) DES RÉSEAUX DE TÉLÉPHONIE MOBILE DANS LA REGION DU GONTOUGOU Du 14/06 au 14/09/2019 |www.valsch-consulting.com TABLE DES MATIERES CHAPITRE 1: CONTEXTE ET GENERALITES ................................................................................................ 3 1.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.1.1 Contexte ...................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 Objectifs de la mission .................................................................................................................. 4 1.1.3 Périmètre de la mission ................................................................................................................ 5 1.1.4 Services à auditer ......................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Protocole de mesure et seuil de référence .................................................................................... 7 1.2.1 Evaluation du niveau de champs radioélectrique .......................................................................... 7 1.2.2 Evaluation du service voix en intra réseau ..................................................................................... 9 1.2.3 Evaluation de la qualité du service SMS ..................................................................................... -

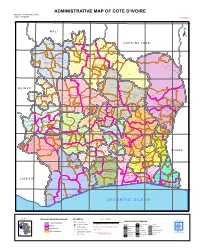

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

Region Du Gontougo

REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE Union-Discipline-Travail MINISTERE DE L’EDUCATION NATIONALE Statistiques Scolaires de Poche 2015-2016 REGION DU GONTOUGO Sommaire Sommaire ................................................................................................. 2 Sigles et Abréviations ................................................................................ 3 Méthodologie ........................................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................. 5 1 / Résultats du Préscolaire 2015-2016 ....................................................... 7 1-1 / Chiffres du Préscolaire en 2015-2016 ............................................. 8 1-2 / Indicateurs du Préscolaire en 2015-2016 ...................................... 14 1-3 / Préscolaire dans les Sous-préfectures en 2015-2016 .................... 15 2 / Résultats du Primaire 2015-2016 ......................................................... 20 2-1 / Chiffres du Primaire en 2015-2016 ................................................ 21 2-2 / Indicateurs du Primaire en 2015-2016 .......................................... 32 2-3 / Primaire dans les Sous-préfectures en 2015-2016 ......................... 35 3/ Résultats du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016 ..................................... 41 3-1 / Chiffres du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016 ................................ 42 3-2 / Indicateurs du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016.......................... -

Rapport D'etude De Bondoukou Analyse Des

RAPPORT D’ETUDE DE BONDOUKOU ANALYSE DES CONFLITS AUTOUR DES SITES MINIERS EN COTE D’IVOIRE: CAS DE LA MINE DE MANGANESE A BOUNDOUKOU Elaboré par : ADOU DJANE DIT FATOGOMA, Docteur en Sociologie/ chercheur (INHP) Consultant-Expert Assistants : - BERTE SALIMATA, Docteur en Sociologie - KONE SEYDOU, Doctorant en sociologie (Mai, 2017) SOMMAIRE SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS .................................................................................................. 3 1 1. Introduction. ........................................................................................................................ 5 2. Méthodologie ...................................................................................................................... 7 2.1. L’approche méthologique ............................................................................................ 7 2.2. Protocole d’introduction sur le terrain ......................................................................... 8 2.2.1. Information des autorités locales et validation des programmes de recherche .... 8 2.2.2. Application des recommandations méthodologiques ........................................... 8 2.3. Fiche technique des applications méthodologiques ................................................... 10 2.4. Difficultés rencontrées sur le terrain.......................................................................... 13 3. Résultats ............................................................................................................................ 14 3.1. Les -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Pdf | 318.08 Kb

6° 5° 4° UNOCI Sikasso B Bobo Dioulasso CÔTE ag o D'IVOIRE 11° Deployment é Orodara lé Kadiana as of 18 Novuember 2004 o MALI Mandiana a B Manankoro BURKINA FASO Tingréla Gaoua i Sa an Niélé nk b é ar ia o ani nd ha m Wa a Wangolodougou o 10° M K Kouto 10° Samatigila BENIN (-) Batié é o g UNMO UNMO a GHANA (-) B UNMO Ferkessédougou UNMO Odienné Boundiali Korhogo Sirana Bouna Sawla Soukourala CÔTE D'IVOIRE GHANA Tafiré Bania Bolé Ba 9° nd Kokpingue a B 9 m o HQ Sector East GHANA ° GUINEA Morondo a u Niakaramandougou R MOROCCO (-) o Beyla u GHANA g Kani e PAKISTAN Dabakala GHANA (-) BANGLADESH (-) GHANA Nassian Touba MOROCCO (-) GHANA UNMO BANGLADESH (-) UNMO Katiola UNMO Bondoukou 8° NIGER Sandegue 8° Séguéla BANGLADESH MOROCCO BANGLADESH (-) Famienkro Tanda Sampa MOROCCO (-) Biankouma BANGLADESH Bouaké NIGER Prikro UNMO Fari M'Babo Adi- NIGER UNMO Zuénoula Yaprikro Berekum Man Djebonoua Koun-Fao Gohitafla FRANCE Mbahiakro Danané BAGLADESH MOROCCO NIGER (-) Kanzra Guezon PAKISTAN Yacouba- Bonoufla Bouaflé Daoukro Agnibilékrou 7 o N ° b Tiebissou 7 Carrefour UNMO z ° o Daloa i BANGLADESH BANGLADESH L Yamoussoukro y UNMO y b Goaso ll e a UNMO n v g a HQ Sector West Zambakro C Duékoué A GHANA UNOCI Abengourou Issia (-) HQ Toulépleu BANGLADESH a Guiglo i BANGLADESH Oumé TOGO Akoupé B BANGLADESH Nz HQ o BANGLADESH UNMO BANGLADESH o Zwedru BANGLADESH n a Gagnoa T 6° UNMO BANGLADESH 6° Taï Divo Agboville NIGER Soubré Lakota Enchi Tiassalé SecGr Pyne Town S GHANA a s s UNMO a n B Sikinssi d r o a u a b Aboisso o o m v a Bingerville LIBERIA a d -

Côte D'ivoire

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT HOSPITAL INFRASTRUCTURE REHABILITATION AND BASIC HEALTHCARE SUPPORT REPUBLIC OF COTE D’IVOIRE COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION MARCH-APRIL 2000 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS, WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES, SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS BASIC DATA AND PROJECT MATRIX i to xii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND DESIGN 1 2.1 Project Objectives 1 2.2 Project Description 2 2.3 Project Design 3 3. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 3 3.1 Entry into Force and Start-up 3 3.2 Modifications 3 3.3 Implementation Schedule 5 3.4 Quarterly Reports and Accounts Audit 5 3.5 Procurement of Goods and Services 5 3.6 Costs, Sources of Finance and Disbursements 6 4 PROJECT PERFORMANCE AND RESULTS 7 4.1 Operational Performance 7 4.2 Institutional Performance 9 4.3 Performance of Consultants, Contractors and Suppliers 10 5 SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT 11 5.1 Social Impact 11 5.2 Environmental Impact 12 6. SUSTAINABILITY 12 6.1 Infrastructure 12 6.2 Equipment Maintenance 12 6.3 Cost Recovery 12 6.4 Health Staff 12 7. BANK’S AND BORROWER’S PERFORMANCE 13 7.1 Bank’s Performance 13 7.2 Borrower’s Performance 13 8. OVERALL PERFORMANCE AND RATING 13 9. CONCLUSIONS, LESSONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 9.1 Conclusions 13 9.2 Lessons 14 9.3 Recommendations 14 Mrs. B. BA (Public Health Expert) and a Consulting Architect prepared this report following their project completion mission in the Republic of Cote d’Ivoire on March-April 2000. -

Cote D Ivoire- Project Upgrade Access Roads to Border Areas Phase 1

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP COTE D'IVOIRE PROJECT TO UPGRADE ACCESS ROADS TO BORDER AREAS PHASE 1 - Public Disclosure Authorized BONDOUKOU-SOKO-GHANA BORDER SEGMENT RDGW/PICU/PGCL DEPARTMENTS December 2018 Translated Document Public DisclosurePublic Authorized TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 STRATEGIC THRUST AND RATIONALE ................................................................................ 1 1.1 Project Background ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Project Linkage with Regional and National Strategies and Objectives ................................................... 1 1.3 Key Development Issues ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Rationale for the Bank’s Involvement ...................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Donor Coordination .................................................................................................................................. 3 2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................ 3 2.1 Project Objectives and Components ......................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Project Type ............................................................................................................................................. -

The Political Economy of the Abron Kingdom of Gyaman

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE ABRON KINGDOM OF GYAMAN Emmanuel Terray* "Money is nothing, the name is what matters*" "~ Prince Kwame Adingra to his secretary, Mr- A.K., c. I960. In the present article we propose to analyse the political economy of the Abron kingdom of Gyaman during the precolonial period. After briefly describing Gyaman's population, history, and political and economic organization, we will describe the various means by which the kingdom obtained its revenues, and the manner in which it spent them. Vie will then examine the administra- tion of "public finances" and its principal agents. Finally, we will describe the changes which were imposed on the entire economy by the coming of colonial rule. I. The territory occupied by the Abron kingdom of Gyaman lies in what is now the northeastern Ivory Coast and northwestern Ghana: it stretches between the Komoe and the Black Volta, on the border of the savannah and the forest. Founded in about I69O by the Gyamanhene Taa Date, the kingdom fell under Ashanti domination in l7aO, and this was maintained for approximately 135 years, despite numerous revolts (l75O, 1^6&, l802~l80a). Gyaman regained its independence only in 1875, after the Ashanti defeat by the English and the destruction of Kumasi by University of Paris. -

Nord-Est De La Côte D'ivoire

75 Dynamisme démographique et mobilité du peuplement dans le Zanzan (Nord-Est de la Côte d’Ivoire) Pascal DENIS, Patrick POTTIER IGARUN – Nantes UMR 6590-CNRS Nantes "Espaces géographiques et sociétés" N’Guessan N’GOTTA IGT - Abidjan Résumé : Enclavée par la nature, les découpages administratifs et la faiblesse de son économie, la région du Zanzan (Nord-Est de la Côte d’Ivoire) n’est pas pour autant inerte ou somnolente. Structures démographiques, mouvements migratoires et mobilité spatiale du semis villageois, en font un territoire contrasté où les processus dynamiques actuellement en cours provoquent des recompositions spatiales d’une certaine ampleur. Mots-clés : Démographie. Migration. Peuplement villageois. Géographie régionale. Abstract : Enclosed by the nature, the administrative structure and the weakness of its economy, the Zanzan region (North-East of Ivory Coast) is not for as much inert or somnolent. Demographic structures, migratory movements and spatial mobility of villages seedling, make some a contrastly territory where currently under way dynamic processes provoke some real spatial recompositions. Key words : Demography. Migrations. Village population. Regional geography. À l’image des dynamiques qui touchent les milieux naturels de la zone tropicale, celles concernant les évolutions et les variations rapides et continues, dans le temps comme dans l’espace, des populations locales ne sont pas sans intérêt. Ainsi, même sur une courte période, les structures démographiques peuvent se modifier en raison d’importants aléas structurels ou conjoncturels, dont les principales causes peuvent être de nature très variée. Alors que, dans ce domaine, l’un des principaux soucis des pays occidentaux sera, dans les décennies à venir, le vieillissement de la population, la plupart des pays du Sud connaissent la situation inverse. -

Côte D'ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire Risk-sensitive Budget Review UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction UNDRR Country Reports on Public Investment Planning for Disaster Risk Reduction This series is designed to make available to a wider readership selected studies on public investment planning for disaster risk reduction (DRR) in cooperation with Member States. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) Country Reports do not represent the official views of UNDRR or of its member countries. The opinions expressed and arguments employed are those of the author(s). Country Reports describe preliminary results or research in progress by the author(s) and are published to stimulate discussion on a broad range of issues on DRR. Funded by the European Union Front cover photo credit: Anouk Delafortrie, EC/ECHO. ECHO’s aid supports the improvement of food security and social cohesion in areas affected by the conflict. Page i Table of contents List of figures ....................................................................................................................................ii List of tables .....................................................................................................................................iii List of acronyms ...............................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgements ...........................................................................................................................v Executive summary .........................................................................................................................