Bronze and Boxwood: Renais- Sance Masterpieces from the Robert H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kunstkammer Wien a Selection of Important

KUNSTKAMMER WIEN A SELECTION OF IMPORTANT OBJECTS „Krumau Madonna“ Prague (?), c. 1400 Sandstone, cloak originally white and blue, hair and edge of clothes gilt Provenance: acquired in 1913 for the Imperial Collections Kunsthistorisches Museum, Kunstkammer, Inv-no. KK 10156 This sculpture was discovered around 1900 in Krumau in southern Bohemia. It is a perfect example of the „beautiful Madonnas“ so popular in the art around 1400. The Virgin with Child is shown as both the Queen of Heaven and a loving mother. Characteristics of courtly refinement, such as the rich and heavy drapery, idealised features and her gilt hair, are combined with verisimilitude, e.g. the body of the baby. This Gothic masterpiece is clearly informed by the art at the court in Prague. Salt Cellar (Saliera) Benvenuto Cellini (Florence 1500 – 1571 Florence) Paris, made between 1540 and 1543 Gold, partly enamelled; ebony, ivory, Provenience: from the Kunstkammer of Archduke Ferdinand II of Tirol at Ambras; presented to the Archduke by King Charles IX of France in 1570 Kunsthistorisches Museum, Kunstkammer, Inv-no. KK 881 The only extant goldsmith work by the celebrated Renaissance artist, Benvenuto Cellini, perfectly reflects the refined taste of contemporary courtly society. We know it served as a container for the expensive spices, salt and pepper, but the complex pictorial programme culminates in an allegory of the cosmos (complete with the god of the ocean and the goddess of the earth, animals, the four winds and the four times of the day) dominated by the arms and emblems of the patron who commissioned it, Francois I of France (ruled 1515-1547). -

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

Roman Lamps Amy Nicholas, ‘11

Roman Lamps Amy Nicholas, ‘11 The University of Richmond’s Ancient World Gallery contains six ancient Roman lamps. One was donated to the Richmond College Museum in 1885 by Colonel J. L. M. Curry, Confederate soldier and congressman, U.S. Minister to Spain, Trustee of Richmond College, and an ardent collector. Another was donated to the Ancient World Gallery in 1980 from the estate of Mae Keller, the first dean of Westhampton College. In 2008, Gertrude Howland donated a Late Roman lamp which she had acquired while traveling in Jordan in 1963. The others probably come from the original collection of the Richmond College Museum, but their donors are unknown. From various time periods and locations, these objects have come together to form a small, but diverse collection of ancient Roman lamps that exemplify a variety of shapes, sizes, and decorations. Oil lamps, some of the most common household items of the ancient world, were used as early as the Stone Age. Usually made of stone or clay, they were the main source of light in ancient times. Indoors, they provided general lighting throughout the household and also in workshops and enterprises. Lamps were also used outdoors at games or religious festivals and have even been found in mass quantities along streets and above doors, where they must have provided street lighting. Used in temples, they served as both sanctuary decoration and votive offerings to gods and goddesses. The main sources of lamps in modern collections, however, are from tombs. As early as the 3rd millennium BCE, lamps were placed in tombs along with other pottery and jewelry. -

Abstracts-Booklet-Lamp-Symposium-1

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses XI Ancient terracotta lamps from Anatolia and the eastern Mediterranean to Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond. Comparative lychnological studies in the eastern parts of the Roman Empire and peripheral areas. An international symposium May 16-17, 2019 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Laurent Chrzanovski Last update: 20/05/2019. Izmir, 2019 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium Logo illustration: An early Byzantine terracotta lamp from Alata in Cilicia; museum of Mersin (B. Gürler, 2004). 1 This symposium is dedicated to Professor Hugo Thoen (Ghent / Deinze) who contributed to Anatolian archaeology with his excavations in Pessinus. 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to the ancient lychnological studies in Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the symposium...................................6-12. Program of the international symposium on ancient lamps in Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond..........................................................................................................................................12-15. Abstracts……………………………………...................................................................................16-67. Constantin -

Stuart Lochhead Sculpture

Stuart Lochhead Sculpture Stuart Lochhead Limited www.stuartlochhead.art 020 3950 2377 [email protected] Auguste Jean-Marie Carbonneaux Paris, 1769-1843 Hercules, after the Antique bronze 73 cm high Signed and dated Carbonneaux 1819 on the right side of the base Related literature ■ E. Lebon, « Répertoire », in Le fondeur et le sculpteur, Paris, Ophrys (« Les Essais de l'INHA »), 2012 [also available online] Stuart Lochhead Limited www.stuartlochhead.art 020 3950 2377 [email protected] Auguste Jean-Marie Carbonneaux is one of the pioneers of the technique of sand-casting for monumental sculpture. Not a lot is known about his life but a recent publication by E. Lebon (see lit.) has shed some light on his career. Born into a family of metal workers, Carbonneaux is known to be active as a founder from 1814. In 1819 at the request of the celebrated sculptor François-Joseph Bosio (1768-1845) he received the prestigious commission to execute the equestrian statue of Louis XIV for the Place des Victoires, Paris, which was unveiled in 1822. Carbonneaux cast the statue and the two men worked together at least one more time since he also executed in bronze Bosio’s large group of Hercules fighting Achelous transformed into a snake, a statue commissioned by the French royal household in 1822, exhibited at the Salon of 1824 and now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris. Clearly recognised as being an excellent founder, Carbonneaux was also selected by the Polish-French count Leon Potocki in 1821 to cast the equestrian portrait of the polish statesman and general Josef Poniatowski by Berthel Thorvaldsen1. -

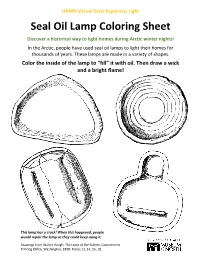

Seal Oil Lamp Coloring Sheet Activity

UAMN Virtual Early Explorers: Light Seal Oil Lamp Coloring Sheet Discover a historical way to light homes during Arctic winter nights! In the Arctic, people have used seal oil lamps to light their homes for thousands of years. These lamps are made in a variety of shapes. Color the inside of the lamp to “fill” it with oil. Then draw a wick and a bright flame! This lamp has a crack! When this happened, people would repair the lamp so they could keep using it. Drawings from Walter Hough, The Lamp of the Eskimo, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1898: Plates 12, 14, 15, 18. UAMN Virtual Early Explorers: Light Seal Oil Lamps Seal oil lamps are important in many Arctic cultures, including the Iñupiat, Yup’ik, Inuit, and Unangan (Aleut) peoples. They were essential for survival in the winter, as the lamps provided light, warmed the home, melted water, and even helped cook food. A seal oil lamp could be the most important object in the home! Right: Sophie Nothstine tends a lamp at the 2019 World Eskimo Indian Olympics. Photo from WEIO. Left: Siberian Yup'ik Lamp from St Lawrence Island, UA2001-005- 0019. Right: Lamp from King Salmon, UA2015-016- 0003. Seal oil lamps were usually made of soapstone, a stone that can be carved and is very resistant to heat. They were sometimes made of pottery or other kinds of stone. Seal oil lamps are made in different shapes and designs to help burn the wick and make the best light possible. The lamp was then filled with oil or fat. -

Adriaen De Vries

E DUVEEN BROTHERS Paris Library Class No. Stock No. ::::::::::::::::::::::: FROM THE LIBRARY OF { <=*Puveen d^fyroiliers, C^Jnc. 720 FIFTH AVE. NEW YORK O/o. /^l M BOUNQ BY S.Georoe Street, MANCHESTER S?W. BEITRÄGE ZUR KUNSTGESCHICHTE NEUE FOLGE. XXV. I ADRIAEN DE VRIES VON CONRAD BUCHWALD O MIT ACHT TAFELN O LEIPZIG VERLAG VON E. A. SEEMANN 1899. Dem Andenken MEINER MUTTER Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/adriaendevriesOObuch Inhalt Seite I. Einleitung I II. Lehrzeit io III. In Augsburg 14 IV. In Diensten Rudolfs II 32 V. Arbeiten für den Fürsten Ernst von Schaumburg 63 VI. Die Brunnen für Fredriksborg und Danzig 74 VII. Aufträge Wallensteins 83 VIII. Schluss 92 IX. Verzeichnis von Werken des Adriaen de Vries 98 Anmerkungen 104 I Einleitung Ein glücklicher Fund war die Veranlassung zu vorliegender Arbeit. In der Kirche des Dorfes Rothsürben unweit Breslaus entdeckte ich zufällig ein gänzlich unbekanntes Werk des Adriaen de Vries. Adriaen de Vries hat keinen Namen in der Kunstgeschichte. Aeltere Nachrichten, die sich über ihn hier und da finden, sind dürftig, auch nicht frei von Widersprüchen und Fehlern. Karl van Mander erwähnt ihn kurz an einzelnen Stellen seines Schilder- buchs, Sandrart bringt zuerst eine Art von Biographie des Künstlers. Er giebt als dessen Geburtsort „Gravenhaag" an und erzählt, dass er „von der Natur selbst zum Bildhauer angetrieben sehr viele Lebens- grosse Bilder von Stein, Wachs und Erden gemacht, solche auch hernachmals in Metall gegossen und sich durch die stete Uebung mehr als kein anderer zu seiner Zeit in Ruhm gebracht, wie dieses seine sehr lobwürdige Werke erstlich in Italien allwo er die Antiken aufs genaueste ergründet an Tag legen, dann er in der Akademie zu Florenz immerzu der beste gewesen". -

Ferdinando Tacca

Ferdinando Tacca (Florence, 1619-1686) Moor with his arms behind his back and one knee resting on a barrel Terracotta 33 cm high Expertise by Sandro Bellesi In a perfect state of conservation, this work of outstanding stylistic merit offers a notably realist interpretation of a powerful male figure with Middle-Eastern features, his right knee resting on a barrel and his hands crossed behind his back. The almost nude figure, leaning forward in a forced position, is characterised by its extreme naturalism deriving from careful preparatory study. This is evident in the impeccable definition of the anatomy, which rigorously emphasises the figure’s vitality through the dynamic muscles, contracted tendons and nerves that palpitate beneath the skin. The energy transmitted by this figure, its face characterised by regular features framed by exotic “Turkish” whiskers, is also splendidly emphasised through the vitality of the gaze or rather through the profound, eloquent eyes. The figure’s anatomical characteristics and in particular the position of the body clearly recall the famous Quattro Mori executed in bronze by Pietro Tacca between 1623 and 1626 for the base of Giovanni Bandini’s Monument to Ferdinand I installed in 1599 on the quayside of Livorno harbour (for the monument and the figures on its base, see A. Brook, Pietro Tacca a Livorno. Il Monumento a Ferdinando I de Medici, Livorno, 2008). As archival and early sources reveal, for the execution of those figures (and the similar ones commissioned for the Monument to Henri IV of France for the Pont Neuf in Paris, subsequently executed by Pietro Francavilla) Tacca made various visits to prisons in Livorno in order to study some of the Saracen pirates captured by the Medici fleet during raids on the Tuscan coastline. -

BM Tour to View

08/06/2020 Gods and Heroes The influence of the Classical World on Art in the C17th and C18th The Tour of the British Museum Room 2a the Waddesdon Bequest from Baron Ferdinand Rothschild 1898 Hercules and Achelous c 1650-1675 Austrian 1 2 Limoges enamel tazza with Judith and Holofernes in the bowl, Joseph and Potiphar’s wife on the foot and the Triumph of Neptune and Amphitrite/Venus on the stem (see next slide) attributed to Joseph Limousin c 1600-1630 Omphale by Artus Quellinus the Elder 1640-1668 Flanders 3 4 see previous slide Limoges enamel salt-cellar of piédouche type with Diana in the bowl and a Muse (with triangle), Mercury, Diana (with moon), Mars, Juno (with peacock) and Venus (with flaming heart) attributed to Joseph Limousin c 1600- 1630 (also see next slide) 5 6 1 08/06/2020 Nautilus shell cup mounted with silver with Neptune on horseback on top 1600-1650 probably made in the Netherlands 7 8 Neptune supporting a Nautilus cup dated 1741 Dresden Opal glass beaker representing the Triumph of Neptune c 1680 Bohemia 9 10 Room 2 Marble figure of a girl possibly a nymph of Artemis restored by Angellini as knucklebone player from the Garden of Sallust Rome C1st-2nd AD discovered 1764 and acquired by Charles Townley on his first Grand Tour in 1768. Townley’s collection came to the museum on his death in 1805 11 12 2 08/06/2020 Charles Townley with his collection which he opened to discerning friends and the public, in a painting by Johann Zoffany of 1782. -

Technology Meets Art: the Wild & Wessel Lamp Factory in Berlin And

António Cota Fevereiro Technology Meets Art: The Wild & Wessel Lamp Factory in Berlin and the Wedgwood Entrepreneurial Model Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 2 (Autumn 2020) Citation: António Cota Fevereiro, “Technology Meets Art: The Wild & Wessel Lamp Factory in Berlin and the Wedgwood Entrepreneurial Model,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 2 (Autumn 2020), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2020.19.2.2. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Accessed: October 30 2020 Fevereiro: The Wild & Wessel Lamp Factory in Berlin and the Wedgwood Entrepreneurial Model Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 2 (Autumn 2020) Technology Meets Art: The Wild & Wessel Lamp Factory in Berlin and the Wedgwood Entrepreneurial Model by António Cota Fevereiro Few domestic conveniences in the long nineteenth century experienced such rapid and constant transformation as lights. By the end of the eighteenth century, candles and traditional oil lamps—which had been in use since antiquity—began to be superseded by a new class of oil-burning lamps that, thanks to a series of improvements, provided considerably more light than any previous form of indoor lighting. Plant oils (Europe) or whale oil (United States) fueled these lamps until, by the middle of the nineteenth century, they were gradually replaced by a petroleum derivative called kerosene. Though kerosene lamps remained popular until well into the twentieth century (and in some places until today), by the late nineteenth century they began to be supplanted by gas and electrical lights. -

Farnese Hercules

FARNESE HERCULES ROMAN, 2ND CENTURY AD MARBLE HEAD RESTORED IN THE 18TH CENTURY HEIGHT: 55 CM. WIDTH: 21 CM. DEPTH: 16 CM. PROVENANCE: IN AN EUROPEAN COLLECTION FROM THE 18TH CENTURY BASED ON THE RESTORATION TECHNIQUES. THEN IN AN AMERICAN PRIVATE COLLECTION FROM THE 1950S. His left leg is forward, slightly flexed, while his supporting leg, the right, is tensed. The position tilts his hips significantly, drawing attention to the prominent muscles of our man’s torso. The inclined line of his hips contrasts with the line of his shoulders, giving the body a pronounced ‘S’ shape. This position, also known as contrapposto, is a Greek invention from the 5th century This statue of a middle-aged man in a BC, introduced by the sculptor Polyclitus. resting position depicts the demi-god At the time, he was looking for the way to Hercules in heroic nudity. Its statuary type perfectly represent the human body and is that of the Farnese Hercules. ultimately devised this new position. 3, Quai Voltaire, 75007 Paris, France – T. +33 1 42 97 44 09 - www.galeriechenel.com Although his head is modern, the craftsmanship is of high quality, reminiscent of late Hellenistic creations. His face and thoughtful, serene expression respect the codes for the representation of the demi- god in statues of this type (Ill. 1). Hercules is hiding his right hand behind his back and, although it is now missing, based on the Farnese Hercules type, we can Ill. 1. Statuette of Hercules resting, Greek, 3rd imagine that he was once holding the apples century BC or Roman replica from the early imperial from the Garden of the Hesperides (Ill. -

Rubens's Theory and Practice of the Imitation of Art Author(S): Jeffrey M

Rubens's Theory and Practice of the Imitation of Art Author(s): Jeffrey M. Muller Source: The Art Bulletin , Jun., 1982, Vol. 64, No. 2 (Jun., 1982), pp. 229-247 Published by: CAA Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3050218 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms CAA is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art Bulletin This content downloaded from 94.71.154.90 on Mon, 01 Feb 2021 11:33:27 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Rubens's Theory and Practice of the Imitation of Art Jeffrey M. Muller Only recently has it been suggested that Rubens informed collector, I was led to question this body of evidence for an his art with theory. Muller Hofstede has proposed to see explanation of the painter's stance towards the art of the Rubens's work in light of the principle "ut pictura poesis" past. The present article therefore considers in depth one as outlined by Lee.' Both Muiller Hofstede and Winner theoretical point: the problem of artistic imitation in have recognized the artist's method of juxtaposing chosen Rubens's thought and practice.