Technology Meets Art: the Wild & Wessel Lamp Factory in Berlin And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman Lamps Amy Nicholas, ‘11

Roman Lamps Amy Nicholas, ‘11 The University of Richmond’s Ancient World Gallery contains six ancient Roman lamps. One was donated to the Richmond College Museum in 1885 by Colonel J. L. M. Curry, Confederate soldier and congressman, U.S. Minister to Spain, Trustee of Richmond College, and an ardent collector. Another was donated to the Ancient World Gallery in 1980 from the estate of Mae Keller, the first dean of Westhampton College. In 2008, Gertrude Howland donated a Late Roman lamp which she had acquired while traveling in Jordan in 1963. The others probably come from the original collection of the Richmond College Museum, but their donors are unknown. From various time periods and locations, these objects have come together to form a small, but diverse collection of ancient Roman lamps that exemplify a variety of shapes, sizes, and decorations. Oil lamps, some of the most common household items of the ancient world, were used as early as the Stone Age. Usually made of stone or clay, they were the main source of light in ancient times. Indoors, they provided general lighting throughout the household and also in workshops and enterprises. Lamps were also used outdoors at games or religious festivals and have even been found in mass quantities along streets and above doors, where they must have provided street lighting. Used in temples, they served as both sanctuary decoration and votive offerings to gods and goddesses. The main sources of lamps in modern collections, however, are from tombs. As early as the 3rd millennium BCE, lamps were placed in tombs along with other pottery and jewelry. -

Intro to Light Fixtures

Intro to Light Fixtures IN THE BEGINNING PRIMITIVE LAMPS - (c 13,000 BC to 3,000 BC) Prehistoric man, used primitive lamps to illuminate his cave. These lamps, made from naturally occurring materials, such as rocks, shells, horns and stones, were filled with grease and had a fiber wick. Lamps typically used animal or vegetable fats as fuel. In the ancient civilizations of Babylonian and Egypt, light was a luxury. The Arabian Nights were far from the brilliance of today. The palaces of the wealthy were lighted only by flickering flames of simple oil lamps. These were usually in the form of small open bowls with a lip or spout to hold the wick. Animal fats, fish oils or vegetable oils (palm and olive) furnished the fuels. Early Developments Early Developments Rush lights: Candles: Tall, grass-like plant dipped in fat Most expensive candles made of beeswax Most common in churches and homes of nobility Snuffers cut the wick while maintaining the flame Early Developments Early Developments New Developments There was a need to improve the light several ways: 1. The need for a constant flame, which could me left unattended for a longer period of time 2. Decrease heat and smoke for interior use 3. To increase the light output 4. An easier way to replenish the source….thus, the development of gas and electricity 5. Produce light with little waste or conserve energy Page 1 Intro to Light Fixtures Industrial Revolution - Europe Gas lamps developed: London well known for gas lamps Argand Lamp Eiffel Tower (1889) originally used gas lamps The Argand burner, which was introduced in 1784 by the Swiss inventor Argand, was a major improvement in brightness compared to traditional open-flame oil lamps. -

Abstracts-Booklet-Lamp-Symposium-1

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses XI Ancient terracotta lamps from Anatolia and the eastern Mediterranean to Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond. Comparative lychnological studies in the eastern parts of the Roman Empire and peripheral areas. An international symposium May 16-17, 2019 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Laurent Chrzanovski Last update: 20/05/2019. Izmir, 2019 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium Logo illustration: An early Byzantine terracotta lamp from Alata in Cilicia; museum of Mersin (B. Gürler, 2004). 1 This symposium is dedicated to Professor Hugo Thoen (Ghent / Deinze) who contributed to Anatolian archaeology with his excavations in Pessinus. 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to the ancient lychnological studies in Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the symposium...................................6-12. Program of the international symposium on ancient lamps in Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond..........................................................................................................................................12-15. Abstracts……………………………………...................................................................................16-67. Constantin -

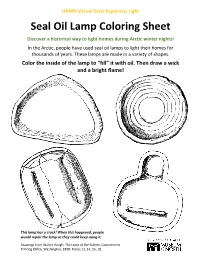

Seal Oil Lamp Coloring Sheet Activity

UAMN Virtual Early Explorers: Light Seal Oil Lamp Coloring Sheet Discover a historical way to light homes during Arctic winter nights! In the Arctic, people have used seal oil lamps to light their homes for thousands of years. These lamps are made in a variety of shapes. Color the inside of the lamp to “fill” it with oil. Then draw a wick and a bright flame! This lamp has a crack! When this happened, people would repair the lamp so they could keep using it. Drawings from Walter Hough, The Lamp of the Eskimo, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1898: Plates 12, 14, 15, 18. UAMN Virtual Early Explorers: Light Seal Oil Lamps Seal oil lamps are important in many Arctic cultures, including the Iñupiat, Yup’ik, Inuit, and Unangan (Aleut) peoples. They were essential for survival in the winter, as the lamps provided light, warmed the home, melted water, and even helped cook food. A seal oil lamp could be the most important object in the home! Right: Sophie Nothstine tends a lamp at the 2019 World Eskimo Indian Olympics. Photo from WEIO. Left: Siberian Yup'ik Lamp from St Lawrence Island, UA2001-005- 0019. Right: Lamp from King Salmon, UA2015-016- 0003. Seal oil lamps were usually made of soapstone, a stone that can be carved and is very resistant to heat. They were sometimes made of pottery or other kinds of stone. Seal oil lamps are made in different shapes and designs to help burn the wick and make the best light possible. The lamp was then filled with oil or fat. -

Optical Measurements of Atmospheric Aerosols: Aeolian Dust, Secondary Organic Aerosols, and Laser-Induced Incandescence of Soot

Optical Measurements of Atmospheric Aerosols: Aeolian Dust, Secondary Organic Aerosols, and Laser-Induced Incandescence of Soot by Lulu Ma, B. S. A Dissertation In Chemistry Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy Approved Jonathan E. Thompson Chair of Committee Dimitri Pappas Carol L. Korzeniewski Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School August, 2013 Copyright 2013, Lulu Ma Texas Tech University, Lulu Ma, August 2013 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Thompson for his guidance and encouragement throughout the past 4 years in Texas Tech University. His profound knowledge, diligence and patience encouraged me and has setup a great example for me in the future. I also thank to Dr. Pappas and Dr. Korzeniewski for their help and for taking time as my committee members. I also would like to thank Dr. Ted Zobeck for his help on soil dust measurements and soil sample collection and also Dr. P. Buseck and his lab for TEM analysis. My group members: Hao Tang, Fang Qian, Kathy Dial, Haley Redmond, Yiyi Wei, Tingting Cao, and Qing Zhang, also helped me a lot in both daily life, and research. At last, I would like to thank my parents and friends for their love and continuous encouragement and support. ii Texas Tech University, Lulu Ma, August 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS……………………………………………………………….ii ABSTRACT ……………………………………………………………………………..vi LIST OF TABLES …………………………………………………………………….viii LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………..………………ix LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ………………………………………….………………xi I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction to Atmospheric Aerosols. ................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Natural Sources ............................................................................................. -

Commentary Kerosene-Based Lighting: an Overlooked Source of Exposure to Household Air Pollution?

Feature: Air quality challenges in low-income settlements Commentary Kerosene-based lighting: an overlooked source of exposure to household air pollution? Ariadna Curto 1,2,3, Cathryn Tonne 1,2,3 1Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), Barcelona, Spain 2Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), Barcelona, Spain 3CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Barcelona, Spain https://doi.org/10.17159/caj/2020/30/1.8420 Access to affordable, reliable, modern and sustainable energy is prolonged periods, resulting in high levels of inhaled pollutants one of the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) set (i.e. more mass inhaled per mass emitted). An experimental by the United Nations for 2030. However, estimates indicate that study in Kenya estimated that night kiosk vendors can inhale progress towards that goal is not on track: 650 million people 1560 µg of fine particles per day emitted by kerosene lamps worldwide are estimated to remain without access to electricity alone (Apple et al., 2010). Relatively few studies have attempted in 2030 (IEA, IRENA, UNSD, WB, WHO, 2019). Nine out of ten of to quantify the contribution of kerosene-based lighting to these people will live in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), mostly in rural particle exposure in populations in SSA. We previously reported communities, which face barriers in terms of affordability and that kerosene-based lighting was the strongest determinant supply. of 24-h average and peak personal exposure to black carbon among women living in a semi-rural area of Mozambique (Curto Without access to affordable and reliable clean energy to et al., 2019). Women who used kerosene as the primary source meet daily cooking, lighting, and heating needs, individuals of lighting had 81% and 93% higher average and peak personal rely on inefficient fuels and technologies that give rise to black carbon exposure, respectively, than those using electricity. -

Rushlight Index 1980-2006

Rushlight Cumulative Index, 1980 – 2006 Vol. 46 – 72 (Pages 2305 – 3951) Part 1: Subject Index Page 2 Part 2: Author Index Page 21 Part 3: Illustration Index Page 25 Notes: The following conventions are used in this index: a slash (/) after the page number indicates the item is an illustration with little or no text. MA before an entry indicates a notice of a magazine article; BR indicates a book review. Please note that if issues were mispaginated, the corrected page numbers are used in this index. The following chart lists the range of pages in each volume of the Rushlight covered by this index. Volume Range of Pages Volume Range of Pages 46 (1980) 2305-2355 60 (1994) 3139-3202 47 (1981) 2356-2406a 61 (1995) 3203-3261 48 (1982) 2406b-2465 62 (1996) 3262-3312 49 (1983) 2465a-2524 63 (1997) 3313-3386 50 (1984) 2524a-2592 64 (1998) 3387-3434 51 (1985) 2593-2679 65 (1999) 3435-3512 52 (1986) 2680-2752 66 (2000) 3513-3569 53 (1987) 2753-2803 67 (2001) 3570-3620 54 (1988) 2804-2851 68 (2002) 3621-3687 55 (1989) 2852-2909 69 (2003) 3688-3745 56 (1990) 2910-2974 70 (2004) 3746-3815 57 (1991) 2974a-3032 71 (2005) 3816-3893 58 (1992) 3033-3083 72 (2006) 3894-3951 59 (1993) 3084-3138 1 Rushlight Subject Index Subject Page Andrews' burning fluid vapor lamps 3400-05 Abraham Gesner: Father of Kerosene 2543-47 Andrews patent vapor burner 3359/ Accessories for decorating lamps 2924 Andrews safety lamp, award refused 3774 Acetylene bicycle lamps, sandwich style 3071-79 Andrews, Solomon, 1831 gas generator 3401 Acetylene bicycle lamps, Solar 2993-3004 -

Lamp Basics Compiled.Pdf

Lamp Basics Lost-in-Time Museum Lamp Fuel One of the earliest types of lamp fuel was animal tallow, usually rendered from beef or mutton fat. Normally solid at room temperatures, it had to be heated to stay liquid. Lamp designs began to emerge in the late 1700’s using lighter fluids, which could travel vertically up a wick and produce a brighter, more efficient light. Whale oil, already used in candle making, was found to be an excellent oil for this new type of lamp. As the market grew, prices for whale oil soared. Burning fluid and camphene, two substitutes for whale oil, were used as early as the 1830’s, but were dangerous due to their flammability. Their use became obsolete as kerosene became more affordable. Kerosene, first produced in 1846 by distilling cannel coal, was commonly referred to as ‘coal oil’. The word "Kerosene", a registered trademark in 1854, eventually became a generic name used by all refiners. While safer and cleaner than burning fluids and camphene, it was expensive and not affordable to the everyday consumer. Kerosene distilled from petroleum revolutionized the lamp fuel market. As production methods became more efficient in the 1860’s, this new type of kerosene, which produced a brighter and cleaner light, gradually became the fuel source used by the general populace. An improved distribution network for natural gas and electricity, along with the technological advancements they made possible, led to the end of kerosene as a primary fuel source. Kerosene is now mainly used for residential heating and as an additive for insecticides and aviation fuel. -

List of Swiss Cultural Goods: Archaeological Objects

List of Swiss cultural goods: archaeological objects A selection compiled by the Conference of Swiss Canton Archaeologists by order of the Federal Office of Culture FOC Konferenz schweizerischer Kantonsarchäologinnen und Kantonsarchäologen KSKA Conférence Suisse des Archéologues Cantonaux CSAC Conferenza Svizzera degli Archeologi Cantonali CSAC Categories of Swiss cultural goods I. Stone A. Architectural elements: made of granite, sandstone, marble and other types of stone. Capitals, window embrasures, mosaics etc. Approximate date: 50 BC – AD 1500. B. Inscriptions: on various types of stone. Altars, tombstones, honorary inscriptions etc. Approximate date: 50 BC – AD 800. C. Reliefs: on limestone and other types of stone. Stone reliefs, tomb- stone reliefs, decorative elements etc. Approximate date: mainly 50 BC – AD 800. D. Sculptures/statues: made of limestone, marble and other types of stone. Busts, statuettes, burial ornaments etc. Approximate date: mainly 50 BC – AD 800. E. Tools/implements: made of flint and other types of stone. Various tools such as knife and dagger blades, axes and implements for crafts etc. Approximate date: 130 000 BC – AD 800. F. Weapons: made of shale, flint, limestone, sandstone and other types of stone. Arrowheads, armguards, cannonballs etc. Approxi- mate date: 10 000 BC – AD 1500. G. Jewellery/accessories: made of various types of stone. Pendants, beads, finger ring inlays etc. Approximate date: mainly 2800 BC – AD 800. II. Metal A. Statues /statuettes / made of non-ferrous metal, rarely from precious metal. busts: Depictions of animals, humans and deities, portrait busts etc. Approximate date: 50 BC – AD 800. B. Vessels: made of non-ferrous metal, rarely from precious metal and iron. -

Analysis of Roman Lamps and a Decorative Lamp Holder 1

The Refined Roman Society: Analysis of Roman Lamps and a Decorative Lamp Holder 1 The Refined Roman Society: Analysis of Roman Lamps and a Decorative Lamp Holder Submission for the Kelsey Experience Jackier Prize Cameron Barnes Student ID: 20155739 AAPTIS 277: The Land of Israel/Palestine Through the Ages Section: Spunaugle - 004 11 April 2014 The Refined Roman Society: Analysis of Roman Lamps and a Decorative Lamp Holder 2 In the words of John R. Clarke (2003), “the Romans were not at all like us” (p. 159). Illuminating the rift between modern customs and those of ancient Rome are the characteristics of two ancient discoveries, which even today convey the nuances of their respective cultural and historical contexts: a terracotta lamp and a bronze lamp holder accompanied by two bronze lamps. In the former artifact, the inscription of a lurid sex scene shocks the modern voyeur, unsuspecting of such a display on an object appearing to be of primarily utilitarian and domestic purposes. Upon the latter objects, intricate bronze craftsmanship speaks of innovative manufacturing techniques while the symbolic presence of owl, dormice, and frog figurines hint at the rich cultural exchange that occurred during the Roman Period. In this essay, I will analyze the manufacturing process, use, and artistry evinced by the aesthetic of selected Roman lamps and a Roman lamp holder in order to compare and contrast the objects while shedding light on the broader cultural context they attest to. The incorporation of artistic detail into the fabrication of these ostensibly functional appliances illustrates the sophistication of Roman society as well as the socioeconomic and cultural motifs of the Roman Period. -

The Origins of Fruits, Fruit Growing, and Fruit Breeding

The Origins of Fruits, Fruit Growing, and Fruit Breeding Jules Janick Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture Purdue University 625 Agriculture Mall Drive West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-2010 I. INTRODUCTION A. The Origins of Agriculture B. Origins of Fruit Culture in the Fertile Crescent II. THE HORTICULTURAL ARTS A. Species Selection B. Vegetative Propagation C. Pollination and Fruit Set D. Irrigation E. Pruning and Training F. Processing and Storage III. ORIGIN, DOMESTICATION, AND EARLY CULTURE OF FRUIT CROPS A. Mediterranean Fruits 1. Date Palm 2. Olive 3. Grape 4. Fig 5. Sycomore Fig 6. Pomegranate B. Central Asian Fruits 1. Pome Fruits 2. Stone fruits C. Chinese and Southeastern Asian Fruits 1. Peach 1 2. Citrus 3. Banana and Plantain 4. Mango 5. Persimmon 6. Kiwifruit D. American Fruits 1. Strawberry 2. Brambles 3. Vacciniums 4. Pineapple 5. Avocado 6. Papaya IV. GENETIC CHANGES AND CULTURAL FACTORS IN DOMESTICATION A. Mutations as an Agent of Domestication B. Interspecific Hybridization and Polyploidization C. Hybridization and Selection D. Champions E. Lost Fruits F. Fruit Breeding G. Predicting Future Changes I. INTRODUCTION Crop plants are our greatest heritage from prehistory (Harlan 1992; Diamond 2002). How, where, and when the domestication of crops plants occurred is slowly becoming revealed although not completely understood (Camp et al. 1957; Smartt and Simmonds 1995; Gepts 2003). In some cases, the genetic distance between wild and domestic plants is so great, maize and crucifers, for example, that their origins are obscure. The origins of the ancient grains (wheat, maize, rice, and sorghum) and pulses (sesame and lentil) domesticated in Neolithic times have been the subject of intense interest and the puzzle is being solved with the new evidence based on molecular biology (Gepts 2003). -

Do Real-Output and Real-Wage Measures Capture Reality? the History of Lighting Suggests Not

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Economics of New Goods Volume Author/Editor: Timothy F. Bresnahan and Robert J. Gordon, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-07415-3 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/bres96-1 Publication Date: January 1996 Chapter Title: Do Real-Output and Real-Wage Measures Capture Reality? The History of Lighting Suggests Not Chapter Author: William D. Nordhaus Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c6064 Chapter pages in book: (p. 27 - 70) Historical Reassessments of Economic Progress This Page Intentionally Left Blank 1 Do Real-Output and Real-Wage Measures Capture Reality? The History of Lighting Suggests Not William D. Nordhaus 1.1 The Achilles Heel of Real Output and Wage Measures Studies of the growth of real output or real wages reveal almost two centu- ries of rapid growth for the United States and western Europe. As figure 1.1 shows, real incomes (measured as either real wages or per capita gross national product [ GNP] ) have grown by a factor of between thirteen and eighteen since the first half of the nineteenth century. An examination of real wages shows that they grew by about 1 percent annually between 1800 and 1900 and at an accelerated rate between 1900 and 1950. Quantitative estimates of the growth of real wages or real output have an oft forgotten Achilles heel. While it is relatively easy to calculate nominal wages and outputs, conversion of these into real output or real wages requires calcula- tion of price indexes for the various components of output.