Ferdinando Tacca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

MARCH 2017 O.XXV No

PQ-COVER 2017.qxp_PQ-COVER MASTER-2007 27/10/2016 15:16 Page 1 P Q PRINT QUARTERLY MARCH 2017 Vol. XXXIV No. 1 March 2017 VOLUME XXXIV NUMBER 1 PQ.JAN17.IFC and IBC.qxp_Layout 1 02/02/2017 16:05 Page 1 PQ.MARCH 2017.qxp_Layout 1 02/02/2017 14:55 Page 1 pRint QuARteRly Volume xxxiV numBeR 1 mARch 2017 contents A proposed intaglio Addition to leonhard Beck’s printed oeuvre 3 BARBARA Butts And mARJoRie B. cohn lelio orsi, Antonio pérez and The Minotaur Before a Broken Labyrinth 11 RhodA eitel-poRteR cornelis Galle i Between Genoa and Antwerp 20 JAmie GABBARelli Franz christoph von scheyb on the Art of engraving 32 thomAs FRAnGenBeRG the drypoints of B. J. o. nordfeldt 42 Julie mellBy notes 53 catalogue and Book Reviews max Klinger 97 Giorgio morandi 104 JeAnnette stoscheK Amy WoRthen m. c. escher 101 marcel duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise 111 √tim o’Riley √stephen J. BuRy R. B. Kitaj 113 AlexAndeR AdAms PQ.MARCH 2017.qxp_Layout 1 02/02/2017 14:55 Page 2 editor Rhoda eitel-porter Administrator sub-editor chris Riches Virginia myers editorial Board clifford Ackley pat Gilmour Jean michel massing david Alexander Antony Griffiths mark mcdonald Judith Brodie craig hartley nadine orenstein michael Bury martin hopkinson peter parshall paul coldwell david Kiehl maxime préaud marzia Faietti Fritz Koreny christian Rümelin Richard Field david landau michael snodin celina Fox Ger luijten ellis tinios david Freedberg Giorgio marini henri Zerner members of print Quarterly publications Registered charity no. 1007928 chairman Antony Griffiths* david Alexander* michael Kauffmann nicolas Barker* david landau* david Bindman* Jane martineau* Graham Brown marilyn perry Fabio castelli tom Rassieur douglas druick pierre Rosenberg Rhoda eitel-porter Alan stone Jan piet Filedt Kok dave Williams david Freedberg henri Zerner George Goldner *directors Between november 1984 and november 1987 Print Quarterly was published in association with the J. -

Encounters Between Tuscany and Lorraine

Originalveröffentlichung in: Strunck, Christina (Hrsg.): Medici women as cultural mediators (1533-1743) = Le donne di casa Medici e il loro ruolo di mediatrici culturali fra le corti d'Europa, Milano 2011, S. 149-181 How Chrestienne Became Cristina Political and Cultural Encounters between Tuscany and Lorraine Christina Strunck While Florence has recently celebrated Caterina and Maria de Medici, the two Florentine queens of France,1 a third highly influential woman, who had close ties to both oi them, has hitherto received only very little attention: Christine of Lorraine, Grand Duchess of luscany (fig. 1). Christine, born in 1565, was Caterina’s favourite grand-daughter and had been raised at the French court since her mother, Caterina’s daughter Claude, had died in childbed in 1575. Caterina instructed the girl in politics’ and arranged the marriage match with her luscan relative, Grand Duke Ferdinando de’ Medici. From her wedding in 1589 until her death in 1636 Christine developed numerous political and cultural initiatives that have left their mark on Florence and Tuscany.'1 She maintained multi-layered relationships both with France and with Lorraine, the latter then still an independent state, governed in turn by Christine s father, Duke Charles Ill (reigned 1559-1608), and her brothers Henry II (1608-1624) and Francois II (1624), before her nephew Charles IV of Lorraine (1624-1675) finally had to accept the French occupation of his duchy.5 Although much could be said about Christine s dealings with the French court and with Maria de’ Medici in particular,1 in this paper I would like to focus only on the relationships between Tuscany and Lorraine sponsored by the Grand Duchess - a topic that has never been the object of sustained investigation. -

Management Plan Men Agement Plan Ement

MANAGEMENTAGEMENTMANAGEMENTEMENTNAGEMENTMEN PLAN PLAN 2006 | 2008 Historic Centre of Florence UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE he Management Plan of the His- toric Centre of Florence, approved T th by the City Council on the 7 March 2006, is under the auspices of the Historic Centre Bureau - UNESCO World Heritage of the Department of Culture of the Florence Municipality In charge of the Management Plan and coordinator of the project: Carlo Francini Text by: Carlo Francini Laura Carsillo Caterina Rizzetto In the compilation of the Management Plan, documents and data provided di- rectly by the project managers have also been used. INDEXEX INDEX INTRODUCTIONS CHAPTER V 45 Introduction by Antonio Paolucci 4 Socio-economic survey Introduction by Simone Siliani 10 V.1 Population indicators 45 V.2 Indicators of temporary residence. 46 FOREWORD 13 V.3 Employment indicators 47 V.4 Sectors of production 47 INTRODUCTION TO THE MANAGEMENT 15 V.5 Tourism and related activities 49 PLANS V.6 Tourism indicators 50 V.7 Access and availability 51 FIRST PART 17 V.8 Traffi c indicators 54 GENERAL REFERENCE FRAME OF THE PLAN V.9 Exposure to various sources of pollution 55 CHAPTER I 17 CHAPTER VI 56 Florence on the World Heritage List Analysis of the plans for the safeguarding of the site I.1 Reasons for inclusion 17 VI.1 Urban planning and safeguarding methods 56 I.2 Recognition of Value 18 VI. 2 Sector plans and/or integrated plans 60 VI.3 Plans for socio-economic development 61 CHAPTER II 19 History and historical identity CHAPTER VII 63 II.1 Historical outline 19 Summary -

Classical Mythology in Florence

Tom Sienkewicz Monmouth College [email protected] Classical Mythology in Florence Museo Archeologico especially the Chimaera, and the François Vase Minos and Scylla, Theseus and the Minotaur (Ovid 8.1-185) Calydonian Boar Hunt (Ovid 8.260-546) Homer. Iliad XXIII (Funeral Games of Patroclus) Ulysses and Polyphemus (Ovid 14.160-220) Classical Mythology at the Duomo Porta della Mandorla, Campanile and Opera del Duomo Orpheus/Eurydice (Ovid 10.1-80) Daedalus/Icarus (Ovid 8.185-260) Public sculpture Piazza della Signoria and Loggia Dei Lanzi. Hercules and Cacus (Ovid. Fasti.1.540ff) Perseus and Medusa (Ovid 4.610-803) Classical Mythology in the Palazzo Vecchio Circe (Ovid 14.240-310) Rape and Intervention of Sabine Women (Livy 1.9-10) Hercules and Nessus (Ovid 9.1-150) Classical Mythology in the Studiolo di Francesco Primo Classical Mythology in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi Rape of Persephone (Ovid 5.380-500) The Mythology in the Public Sculpture of Florence Apollo and Daphne 1.450-570 Classical Mythology in the Bargello Classical Mythology in the Uffiizi Classical Mythology in the Pitti Palace Classical Mythology in the Boboli Gardens especially the Grotta of Buontalenti Classical Mythology in the Medici Villa at Poggio a Caiano Hercules in Florence The François Vase c.570 B.C. found in tomb at Fonte Rotella near Chiusi in 1844-45 Made by Ergotomos Painted by Kleitias Side A Side B Calydonian Boar Hunt Theseus' Crane Dance The Funeral Games of Patroclus Battle of Lapiths and Centaurs The Marriage of Peleus and Thetis The Marriage -

Pietro Tacca Hofbildhauer Der Medici (1577–1640)

Jessica Mack-Andrick PIETRO TACCA HOFBILDHAUER DER MEDICI (1577–1640) Jessica Mack-Andrick PIETRO TACCA HOFBILDHAUER DER MEDICI (1577–1640) Politische Funktion und Ikonographie des frühabsolutistischen Herrscherdenkmals unter den Großherzögen Ferdinando I., Cosimo II. und Ferdinando II. Weimar 2005 Bamberg: Univ., Diss., 2003 © VERLAG UND DATENBANK FÜR GEISTESWISSENSCHAFTEN, WEIMAR 2005 Kein Teil dieses Werkes darf ohne schriftliche Einwilligung des Verlages in irgendeiner Form (Fotokopie, Mikrofilm oder ein anderes Verfahren) reproduziert oder unter Verwen- dung elektronischer Systeme verarbeitet, vervielfältigt oder verbreitet werden. Verlag und Autor haben sich nach besten Kräften bemüht, die erforderlichen Reproduktionsrechte für alle Abbildungen einzuholen. Für den Fall, dass wir etwas übersehen haben, sind wir für Hinweise der Leser dankbar. Layout & Satz: Anja Schreiber, Druck: VDG ISBN 3-89739-483-9 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. EINLEITUNG ........................................................................................................... 11 1.1 Gegenstand und Zielsetzung .......................................................................11 1.2 Methodische Vorgehensweise und Forschungsbericht .............................. 17 2. PIETRO TACCA UND SEINE AUFTRAGGEBER .......................................... 23 2.1 Ferdinando I. (1587–1609) ............................................................................ 23 2.1.1 „Tutte le qualità necessarie per un ottimo Principe“ – Ferdinando I. und das absolutistische Herrscherideal -

Benjamin Proust Fine Art Limited London

london fall 2018 fall TEFAF NEW YORK NEW YORK TEFAF fine art limited benjamin proust benjamin TEFAF NEW YORK 2018 BENJAMIN PROUST LONDON benjamin proust fine art limited london TEFAF NEW YORK fall 2018 CONTENTS important 1. ATTRIBUTED TO LUPO DI FRANCESCO VIRGIN AND CHILD european 2. SIENA, EARLY 14TH CENTURY sculpture SEAL OF THE COMMUNAL WHEAT OF SIENA 3. FLORENCE, LATE 15TH CENTURY BUST OF A BOY 4. PIERINO DA VINCI TWO CHILDREN HOLDING A FISH 5. ATTRIBUTED TO WILLEM VAN TETRODE BUST OF TIBERIUS 6. FLORENCE OR ROME, FIRST HALF 17TH CENTURY FLORA FARNESE 7. ATTRIBUTED TO HUBERT LE SUEUR HERCULES AND TELEPHUS antiquities 8. KAVOS, EARLY CYCLADIC II LYRE-SHAPED HEAD & modern 9. GREEK, LATE 5TH CENTURY BC drawings ATTIC BLACK-GLAZED PYXIS 10. IMPERIAL ROMAN OIL LAMP 11. AUGUSTE RODIN FEMME NUE ALLONGÉE 12. AUGUSTE RODIN NAKED WOMAN IN A FUR COAT 13. PIERRE BONNARD PAYSAGE DE VERNON benjamin proust Having first started at the Paris flea market, Benjamin Proust trained with international-level art dealers, experts and auctioneers in France and Belgium, setting up his own gallery in Brussels in 2008. In 2012, Benjamin moved his activity to New Bond Street, in the heart of Mayfair, London’s historic art district, where it has been located ever since. A proud sponsor of prominent British institutions such as The Wallace Collection and The Courtauld Gallery in London, Benjamin Proust Fine Art focuses on European sculpture and works of art, with a particular emphasis on bronzes and the Renaissance. Over the years, our meticulous sourcing, in-depth research, and experience in solving provenance issues, all conducted with acknowledged honesty and professionalism, have been recognized by a growing number of major international museums, with whom long-standing relationships have been established. -

Cristo Vivo Carved Boxwood 26 Cm

ITALIAN SCHOOL, CIRCA 1600 Cristo Vivo Carved boxwood 26 cm RELATED LITERATURE: DESJARDINS, A. La vie et l'oeuvre de Jean Bologne, d'après les manuscrits inédits recueillis par Foucques de Vagnonville. Paris: A. Quantin, 1883. DHANENS, E. Jean Boulogne, Giovanni Bologna Fiammingo. Brussels: Paleis der Academiën, 1956. Giambologna, 1529-1608, Sculptor to the Medici. Exhibition catalogue. London: The Council, 1978. AVERY, Ch. Giambologna. The complete sculpture. London: Phaidon Press, 1993. COPPEL AREIZAGA R. «Giambologna y los crucifijos enviados a España», Goya: revista de arte, 301-302, 2004, pp. 201-214. This exceptional Living Christ is based on a model created by Giambologna (Douai, 1529 - Florence, 1608), the great bronze sculptor of his day who took his starting point from the classical sculptures that had so impressed him during his time in Rome. These provided the basis for the creation of a personal style based on technical virtuosity and a profound interest in anatomical study, movement and multiple viewpoint, leading to exaggerated contrapposto and the figura serpentinata. Giambologna specialised in a wide range of subjects ranging from classical mythology to allegory, portraiture, religious scenes and animals; works executed in both bronze and marble and on every scale. The artist’s extremely active studio provided training to sculptors such as Pietro Tacca, Giambologna’s successor, Antonio Susini, his principal assistant, Pietro Francavilla and Adriaen de Vries, all of whom disseminated his style among the courts of Europe. This, and the fact that his patrons the Medici used his works as high level diplomatic gifts, was a significant factor in the success of this artist, whose works have continued to be admired and reproduced to the present day. -

Caravaggio's Roman Patron Del Monte As a Florentine

ABSTRACT Title of Document: IN THE GRACES OF HIS HIGHNESS THE GRAND DUKE: CARAVAGGIO’S ROMAN PATRON DEL MONTE AS A FLORENTINE COURTIER AND AGENT Marie J. Ladino Master of Arts 2009 Directed By: Dr. Anthony Colantuono Associate Professor Department of Art History and Archaeology While Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte is celebrated as Caravaggio’s first major patron in Rome, his primary activities at the turn of the seventeenth century were, in reality, centered much more around his role as a courtier and an artistic agent working on behalf of Ferdinando I de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. In order to further the grand duke’s propagandistic agenda for himself and his state, the cardinal, from his position in Rome, advised Ferdinando on opportunities to buy and commission works of art. He also gave gifts to the sovereign, such as Caravaggio’s Medusa , always with the grand duke’s artistic aims in mind. Del Monte should indeed be thought of as a patron of the arts; however, his relationship with the Florentine court sheds light on an essential but perhaps understudied position within the mechanism of Italian patronage—that of the agent who works on behalf of another. IN THE GRACES OF HIS HIGHNESS THE GRAND DUKE: CARAVAGGIO’S ROMAN PATRON DEL MONTE AS A FLORENTINE COURTIER AND AGENT By Marie Jacquelin Ladino Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2009 Advisory Committee: Professor Anthony Colantuono, Chair Professor Meredith Gill Professor Yui Suzuki © Copyright by Marie Jacquelin Ladino 2009 Disclaimer The thesis document that follows has had referenced material removed in respect for the owner's copyright. -

Collaborative Painting Between Minds and Hands: Art Criticism, Connoisseurship, and Artistic Sodality in Early Modern Italy

Collaborative Painting Between Minds and Hands: Art Criticism, Connoisseurship, and Artistic Sodality in Early Modern Italy by Colin Alexander Murray A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Colin Murray 2016 Collaborative Painting Between Minds and Hands: Art Criticism, Connoisseurship, and Artistic Sodality in Early Modern Italy Colin Alexander Murray Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto 2016 Abstract The intention of this dissertation is to open up collaborative pictures to meaningful analysis by accessing the perspectives of early modern viewers. The Italian primary sources from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries yield a surprising amount of material indicating both common and changing habits of thought when viewers looked at multiple authorial hands working on an artistic project. It will be argued in the course of this dissertation that critics of the seventeenth century were particularly attentive to the practical conditions of collaboration as the embodiment of theory. At the heart of this broad discourse was a trope extolling painters for working with what appeared to be one hand, a figurative and adaptable expression combining the notion of the united corpo and the manifold meanings of the artist’s mano. Hardly insistent on uniformity or anonymity, writers generally believed that collaboration actualized the ideals of a range of social, cultural, theoretical, and cosmological models in which variously formed types of unity were thought to be fostered by the mutual support of the artists’ minds or souls. Further theories arose in response to Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo’s hypothesis in 1590 that the greatest painting would combine the most highly regarded old masters, each contributing their particular talents towards the whole. -

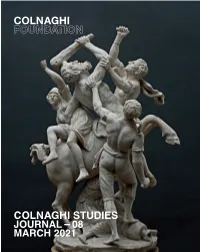

Journal 08 March 2021 Editorial Committee

JOURNAL 08 MARCH 2021 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Stijn Alsteens International Head of Old Master Drawings, Patrick Lenaghan Curator of Prints and Photographs, The Hispanic Society of America, Christie’s. New York. Jaynie Anderson Professor Emeritus in Art History, The Patrice Marandel Former Chief Curator/Department Head of European Painting and JOURNAL 08 University of Melbourne. Sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Jennifer Montagu Art Historian specializing in Italian Baroque. Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Scott Nethersole Senior Lecturer in Italian Renaissance Art, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Andrea Bacchi Director, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna. Larry Nichols William Hutton Senior Curator, European and American Painting and Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is to publish texts on significant Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Sculpture before 1900, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition that have recently come to light or about which new research is Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Honorary Associate in Art History, Tom Nickson Senior Lecturer in Medieval Art and Architecture, Courtauld Institute of Art, underway, as well as on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the broader context The Open University. London. of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. Francesca Baldassari Professor, Università degli Studi di Padova. Gianni Papi Art Historian specializing in Caravaggio. Bonaventura Bassegoda Catedràtic, Universitat Autònoma de Edward Payne Assistant Professor in Art History, Aarhus University. Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Editorial Committee, composed of Barcelona. -

The Santissima Annunziata of Florence, Medici Portraits, and the Counter Reformation in Italy

THE SANTISSIMA ANNUNZIATA OF FLORENCE, MEDICI PORTRAITS, AND THE COUNTER REFORMATION IN ITALY by Bernice Ida Maria Iarocci A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Bernice Iarocci 2015 THE SANTISSIMA ANNUNZIATA OF FLORENCE, MEDICI PORTRAITS, AND THE COUNTER REFORMATION IN ITALY Bernice Ida Maria Iarocci Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto 2015 A defining feature of the Counter-Reformation period is the new impetus given to the material expression of devotion to sacred images and relics. There are nonetheless few scholarly studies that look deeply into the shrines of venerated images, as they were renovated or decorated anew during this period. This dissertation investigates an image cult that experienced a particularly rich elaboration during the Counter-Reformation – that of the miracle-working fresco called the Nunziata, located in the Servite church of the Santissima Annunziata in Florence. By the end of the fifteenth century, the Nunziata had become the primary sacred image in the city of Florence and one of the most venerated Marian cults in Italy. My investigation spans around 1580 to 1650, and includes texts related to the sacred fresco, copies made after it, votives, and other additions made within and around its shrine. I address various components of the cult that carry meanings of civic importance; nonetheless, one of its crucial characteristics is that it partook of general agendas belonging to the Counter- Reformation movement. That is, it would be myopic to remain within a strictly local scope when considering this period.