Democracy Some Acute Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detroit Audubon's 2017 Earth Day

A publication of Detroit Audubon • www.detroitaudubon.org Spring 2017 • Vol. 2017, Issue 1 DETROIT AUDUBON’S 2017 EARTH DAY CELEBRATION/TEACH-IN - “SOARING TO NEW HEIGHTS!” Celebrate the 47th Earth Day, Saturday, April 22 at the Downriver Campus Wayne County Community College, 21000 Northline Rd., Taylor, MI In collaboration with the Continuing Education Department at Wayne County Julie Beutel, folksinger and peace and justice activist, is well known Community College District, Detroit Audubon presents the annual Earth Day locally for singing at many peace and justice rallies. She produces Celebration and Teach-In April 22, to help educate the community about the concerts for other local musicians, hosting house concerts in Detroit. environment and celebrate our precious planet. Presentations and events include. She has a rich and expressive voice. She is also an accomplished Don Sherwood M.S., retired Community College Professor of actress, including playing Clara Ford in the opera, “The Forgotten,” Biology and Downriver resident, is a lifelong birder with experience narrating documentaries, and doing other voiceover work. She is fluent in Spanish, as an assistant bird bander and raptor rehabilitator. Presently he is having lived in Spain for one year and Nicaragua for two years. She has performed a volunteer counter with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s annual at other Detroit Audubon conferences, most recently at the Detroit Zoo. Detroit River Hawkwatch at Lake Erie Metropark. Sherwood knows the Joe Rogers received a biology degree from Central Michigan University, and spent flora and fauna surrounding the WCCC Downriver Campus, where he has observed many years in the field studying raptors, including nest studies of Bald Eagles, over 130 bird species over three decades. -

Global Austria Austria’S Place in Europe and the World

Global Austria Austria’s Place in Europe and the World Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser (Eds.) Anton Pelinka, Alexander Smith, Guest Editors CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | Volume 20 innsbruck university press Copyright ©2011 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, ED 210, 2000 Lakeshore Drive, New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Book design: Lindsay Maples Cover cartoon by Ironimus (1992) provided by the archives of Die Presse in Vienna and permission to publish granted by Gustav Peichl. Published in North America by Published in Europe by University of New Orleans Press Innsbruck University Press ISBN 978-1-60801-062-2 ISBN 978-3-9028112-0-2 Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Fritz Plasser, Universität Innsbruck Production Editor Copy Editor Bill Lavender Lindsay Maples University of New Orleans University of New Orleans Executive Editors Klaus Frantz, Universität Innsbruck Susan Krantz, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Helmut Konrad Universität Graz Universität -

Diplomarbeit "Justiz Und Verwaltung Im Spannungsfeld Zwischen Recht Und Politik" Mag

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES 1 Diplomarbeit "Justiz und Verwaltung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Recht und Politik" Mag. Dr. iur. Robert TODER Mag. phil. Wien, im Oktober 2008 Studienkennzahl A 300 Politikwissenschaft Betreuer: o. Univ. Prof. Dr. iur. Peter GERLICH 2 1. Grundsätzliches und staatstheoretische Überlegungen……………………………….................6 1.1. Einleitung………………………………….................................................................................6 1.2. Begriffsbestimmungen und theoretische Grundsatzüberlegungen………………………….….6 1.2.1. Der Staat………………………………….............................................................................…6 1.2.1.1. Definition des Staates im Sinne der Politikwissenschaft…………………………………...…7 1.2.1.2. Definition des Staates im Sinne der Soziologie…………………………………....................8 1.2.1.3. Definition des Staates im Sinne der Allgemeinen Staatslehre……………………………….8 1.2.1.4. Das Staatsgebiet…………………………………..................................................................9 1.2.1.5. Das Staatsvolk…………………………………..................................................................…9 1.2.1.6 Die Staatsgewalt………………………………….................................................................11 1.2.1.7. Der Staat im verfassungsrechtlichen Sinn…………………………………..........................12 1.2.1.8. Der Staat im völkerrechtlichen Sinn…………………………………...................................12 1.2.1.9. Die Definition des Staates im strafrechtlichen Sinn…………………………………............13 -

The Marshall Plan in Austria 69

CAS XXV CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIANAUSTRIAN STUDIES STUDIES | VOLUME VOLUME 25 25 This volume celebrates the study of Austria in the twentieth century by historians, political scientists and social scientists produced in the previous twenty-four volumes of Contemporary Austrian Studies. One contributor from each of the previous volumes has been asked to update the state of scholarship in the field addressed in the respective volume. The title “Austrian Studies Today,” then, attempts to reflect the state of the art of historical and social science related Bischof, Karlhofer (Eds.) • Austrian Studies Today studies of Austria over the past century, without claiming to be comprehensive. The volume thus covers many important themes of Austrian contemporary history and politics since the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1918—from World War I and its legacies, to the rise of authoritarian regimes in the 1930s and 1940s, to the reconstruction of republican Austria after World War II, the years of Grand Coalition governments and the Kreisky era, all the way to Austria joining the European Union in 1995 and its impact on Austria’s international status and domestic politics. EUROPE USA Austrian Studies Studies Today Today GünterGünter Bischof,Bischof, Ferdinand Ferdinand Karlhofer Karlhofer (Eds.) (Eds.) UNO UNO PRESS innsbruck university press UNO PRESS UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Austrian Studies Today Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 25 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2016 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

The Oxfordian Volume 21 October 2019 ISSN 1521-3641 the OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019

The Oxfordian Volume 21 October 2019 ISSN 1521-3641 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 The Oxfordian is the peer-reviewed journal of the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship, a non-profit educational organization that conducts research and publication on the Early Modern period, William Shakespeare and the authorship of Shakespeare’s works. Founded in 1998, the journal offers research articles, essays and book reviews by academicians and independent scholars, and is published annually during the autumn. Writers interested in being published in The Oxfordian should review our publication guidelines at the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship website: https://shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org/the-oxfordian/ Our postal mailing address is: The Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship PO Box 66083 Auburndale, MA 02466 USA Queries may be directed to the editor, Gary Goldstein, at [email protected] Back issues of The Oxfordian may be obtained by writing to: [email protected] 2 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 Acknowledgements Editorial Board Justin Borrow Ramon Jiménez Don Rubin James Boyd Vanessa Lops Richard Waugaman Charles Boynton Robert Meyers Bryan Wildenthal Lucinda S. Foulke Christopher Pannell Wally Hurst Tom Regnier Editor: Gary Goldstein Proofreading: James Boyd, Charles Boynton, Vanessa Lops, Alex McNeil and Tom Regnier. Graphics Design & Image Production: Lucinda S. Foulke Permission Acknowledgements Illustrations used in this issue are in the public domain, unless otherwise noted. The article by Gary Goldstein was first published by the online journal Critical Stages (critical-stages.org) as part of a special issue on the Shakespeare authorship question in Winter 2018 (CS 18), edited by Don Rubin. It is reprinted in The Oxfordian with the permission of Critical Stages Journal. -

Österreichs Wirtschaft Lenkt

Wer Österreichs Wirtschaft lenktVon Martina Forsthuber, Thomas Martinek und Peter Sempelmann ENÉ PROHASKA, R IEMENS ÖSTERREICH, IEMENS ÖSTERREICH, S LGNER, WALTER WOBRAZEK (2), WOBRAZEK WALTER LGNER, I UKAS L MACHTANDREAS LEITNER; ILLUSTRATION: eorg Pölzl hat viele Qualitäten, die ihn für den Job des neuen Post-Chefs qualifizieren. Aber die wichtigste ist wohl: Pölzl besitzt ein hoch entwi- Gckeltes Gespür für den gezielten Einsatz von Macht. Im Juni 2005 führte Niederösterreichs Landeshauptmann Erwin Pröll die Handymastensteuer ein. Pölzl, damals Chef von T-Mobile, wollte das nicht schlucken. Von geschickten Be- ratern eingefädelt, fand im zwölften Stock eines Hoch- hauses am Donaukanal in Wien ein diskretes Treffen statt. Und wenig später erschien in Österreichs größter und ein- flussreichster Tageszeitung, der „Kronen Zeitung“, ein Ar- tikel mit der Überschrift: „Österreicher gegen Handymas- tensteuer“. Es sollte nicht die einzige Story mit diesem Tenor bleiben. Der Machtkampf war entschieden: Die Mobilfunker gelobten, ihre Masten in Zukunft gemeinsam zu nutzen, und Pröll trat den geordneten Rückzug an. Am 15. Dezem- ber 2005 wurde im niederösterreichischen Landtag die Handymastensteuer wieder abgeschafft. Obwohl der Post-Aufsichtsrat gerne ein Loblied auf sei- ne Unabhängigkeit singt: Pölzl würde nicht im Oktober als General eines der wichtigsten heimischen Konzerne antreten, hätten Verbündete nicht für ihn in der ÖVP Stimmung gemacht und hätte er nicht die guten Kontakte zu SPÖ-Kanzler Werner Faymann genützt – kurz ge- > EBOR D ICHEL- M EIDI H ICTUREDESK.COM, ICTUREDESK.COM, P ICHARD/WIRTSCHAFTSBLATT/ R TANZER CHOTT (2), CHOTT S AUSCH- R ICHAEL ICHAEL M MACHTJuli 2009 | trend 7 51 Defilee am roten Teppich bei den Salzburger Festspielen: Siemens-Österreich-Vorstands- vorsitzende Brigitte Ederer mit Salzburgs Landeshauptfrau Gabi Burgstaller und Festspiele-Präsiden- tin Helga Rabl-Stadler (v. -

2011-2012 Wisconsin Blue Book: Statistics

STATISTICS: HISTORY 679 HIGHLIGHTS OF HISTORY IN WISCONSIN History — On May 29, 1848, Wisconsin became the 30th state in the Union, but the state’s written history dates back more than 300 years to the time when the French first encountered the diverse Native Americans who lived here. In 1634, the French explorer Jean Nicolet landed at Green Bay, reportedly becoming the first European to visit Wisconsin. The French ceded the area to Great Britain in 1763, and it became part of the United States in 1783. First organized under the Northwest Ordinance, the area was part of various territories until creation of the Wisconsin Territory in 1836. Since statehood, Wisconsin has been a wheat farming area, a lumbering frontier, and a preeminent dairy state. Tourism has grown in importance, and industry has concentrated in the eastern and southeastern part of the state. Politically, the state has enjoyed a reputation for honest, efficient government. It is known as the birthplace of the Republican Party and the home of Robert M. La Follette, Sr., founder of the progressive movement. Political Balance — After being primarily a one-party state for most of its existence, with the Republican and Progressive Parties dominating during portions of the state’s first century, Wisconsin has become a politically competitive state in recent decades. The Republicans gained majority control in both houses in the 1995 Legislature, an advantage they last held during the 1969 session. Since then, control of the senate has changed several times. In 2009, the Democrats gained control of both houses for the first time since 1993; both houses returned to Republican control in 2011. -

03 Tätigkeitsbericht Vfgh 2014 (Gescanntes Original) 1 Von 70

III-221 der Beilagen XXV. GP - Bericht - 03 Tätigkeitsbericht vfgh 2014 (gescanntes Original) 1 von 70 scheiden. 2014 Tätigkeitsbericht •• .•••. :.:. v f 9 h Verfassungsgerichtshof Österreich www.parlament.gv.at 2 von 70 III-221 der Beilagen XXV. GP - Bericht - 03 Tätigkeitsbericht vfgh 2014 (gescanntes Original) www.parlament.gv.at III-221 der Beilagen XXV. GP - Bericht - 03 Tätigkeitsbericht vfgh 2014 (gescanntes Original) 3 von 70 . : : . : : : vfg h Verfassu ng sgerichtshof Österreich BERICHT DES VERFASSUNGSGERICHTSHOFES •• •• UBER SEINE TATIGKEIT IM JAHR 2014 www.parlament.gv.at 4 von 70 III-221 der Beilagen XXV. GP - Bericht - 03 Tätigkeitsbericht vfgh 2014 (gescanntes Original) Impressum Medieninhaber: Verfassungsgerichtshof, Freyung 8, 1010 Wien www.parlament.gv.at III-221 der Beilagen XXV. GP - Bericht - 03 Tätigkeitsbericht vfgh 2014 (gescanntes Original) 5 von 70 INHALTSÜBERSICHT 1. ALLGEMEINES . ....... ........... ... ........... ...... ... .. ............................................ 5 1.1. Reform der Verwaltungsgerichtsbarkeit ............................................. 5 1.2. Gesetzesbeschwerde ................ .......................................................... 5 1.3. Reform der Untersuchungsausschüsse ............. ... .............................. 6 1.4. Wahrnehmungen .... ....... .............................................................. 7 2. PERSONELLE STRUKTUR DES VERFASSUNGSGERICHTSHOFES ......... ........... 8 2.1. Kollegium des Verfassungsgerichtshofes .......... ................. ............... -

The Bulletin

THE BULLETIN The Bulletin is a publication of the European Commission for Democracy through Law. It reports regularly on the case-law of constitutional courts and courts of equivalent jurisdiction in Europe, including the European Court of Human Rights and the Court of Justice of the European Communities, as well as in certain other countries of the world. The Bulletin is published three times a year, each issue reporting the most important case-law during a four months period (volumes numbered 1 to 3). The last two volumes of the series concerning the same year are actually published and delivered in the following year, i.e. volume 1 of the 2002 Edition in 2002, volumes 2 and 3 in 2003. Its aim is to allow judges and constitutional law specialists to be informed quickly about the most important judgments in this field. The exchange of information and ideas among old and new democracies in the field of judge-made law is of vital importance. Such an exchange and such cooperation, it is hoped, will not only be of benefit to the newly established constitutional courts, but will also enrich the case-law of the existing courts. The main purpose of the Bulletin on Constitutional Case-law is to foster such an exchange and to assist national judges in solving critical questions of law which often arise simultaneously in different countries. The Commission is grateful to liaison officers of constitutional and other equivalent courts, who regularly prepare the contributions reproduced in this publication. As such, the summaries of decisions and opinions published in the Bulletin do not constitute an official record of court decisions and should not be considered as offering or purporting to offer an authoritative interpretation of the law. -

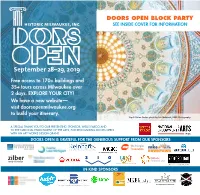

Doors Open Block Party See Inside Cover for Information

DOORS OPEN BLOCK PARTY SEE INSIDE COVER FOR INFORMATION Free access to 170+ buildings and 35+ tours across Milwaukee over 2 days. EXPLORE YOUR CITY! We have a new website— visit doorsopenmilwaukee.org to build your itinerary. Tripoli Shrine Center, photo by Jon Mattrisch, JMKE Photography A SPECIAL THANK YOU TO OUR PRESENTING SPONSOR, WELLS FARGO AND TO THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT OF THE ARTS, FOR RECOGNIZING DOORS OPEN WITH AN ART WORKS DESIGN GRANT. DOORS OPEN IS GRATEFUL FOR THE GENEROUS SUPPORT FROM OUR SPONSORS IN-KIND SPONSORS DOORS OPEN MILWAUKEE BLOCK PARTY & EVENT HEADQUARTERS East Michigan Street, between Water and Broadway (the E Michigan St bridge at the Milwaukee River is closed for construction) Saturday, September 28 and Sunday, September 29 PICK UP AN EVENT GUIDE ANY TIME BETWEEN 10 AM AND 5 PM BOTH DAYS ENJOY MUSIC WITH WMSE, FOOD VENDORS, AND ART ACTIVITIES FROM 11 AM TO 3 PM BOTH DAYS While you are at the block party, visit the Before I Die wall on Broadway just south of Michigan St. We invite the public to add their hopes and dreams to this art installation. Created by the artist Candy Chang, Before I Die is a global art project that invites people to contemplate mortality and share their personal aspirations in public. The Before I Die project reimagines how walls of our cities can help us grapple with death and meaning as a community. 2 VOLUNTEER Join hundreds of volunteers to help make this year’s Doors Open a success. Volunteers sign up for at least one, four-hour shift to help greet and count visitors at each featured Doors Open site throughout the weekend. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit „Wo Recht zu Unrecht wird, wird Widerstand zur Pflicht“ Was macht Journalismus aus politischen Strategien – eine Analyse am Beispiel der Auseinandersetzung zwischen der Kärntner Politik und dem slowenischen Interessensvertreter Rudi Vouk zur Durchsetzung der zweisprachigen Ortstafelfrage Verfasserin Sabina Zwitter-Grilc angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienbuchblatt: A 301/295 Studienrichtung lt. Studienbuchblatt: Publizistik- und Kommunikationswiss./ Gewählte Fächer statt 2. Studienrichtg. Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Friedrich Hausjell VORWORT ................................................................................................6 1. EINLEITUNG .........................................................................................9 2. DAS ERKENNTNISINTERESSE ......................................................... 10 2.1. Die Forschungsfragen ...................................................................................................... 10 2.2. Das theoretische Fundament.......................................................................................... 11 2.2.1. Die Kommunikationstheorien ...................................................................................... 11 2.2.2. Die analytischen Kategorien von Menz, Lalouschek und Dressler........................ 14 2.3. Narration, Dekonstruktion und Ethnisierung -

Marina 7-10-18 Resume

Marina Lee Beginning Dreams forever, LLC 833 East Burleigh Street • Milwaukee, WI 53212-2210 • (414) 562-3037 email [email protected] • [email protected] website marinalee.com BEGINNING FOUNDED 1992 DREAMS Education • BFA Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design f o r e v e r • Pacific Northwest College of Art Public and Community Art 2018 ‘Peace in the Streets’ mandala peace symbols chalked by MPS students for their City Wide Arts Festival at Summerfest grounds ‘Sapphire’ a magical dragon created by Indian Hill students for their garden 2017 ‘Amani is Peace’ Collaborative fiberglass letter sculptures with Nova students. Snail’s Crossing: Fratney and Pierce students design benches and community builds and paints. Single log seating painted by community. ‘Peace in the Streets’ mandala peace stencil painting Riverwest Community Garden, Westside Academy, Cushing Elementary and Brookfield Elementary. ‘Peaces of Eight’ - Sculpture in the City by Althoff Catholic High School students 2016 Bayview Campus Donor Mosaic Wall in collaboration with Ann Wydeven and MCFI clients ‘Peace, Character and Justice’ Painted murals, laminated student work and a fiberglass bench designed by students from SCTE and Barack Obama School ‘Growth’ outdoor sculpture for garden, Edgerton Elementary, Hales Corners. ‘La Luna’ and ‘The Fish’ - Sculpture in the City by Belleville East students, IL 2015 ‘Compassion’ collaborative sculpture with Ann Wydeven, Kennedy and youth from Urban Underground and Sherman Park Neighbors ‘Water, Water’ 5 benches designed and created