A Field Guide to Place: Lessons on Home, Landscape, and Transformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21 -

Region Forest Number Forest Name Wilderness Name Wild

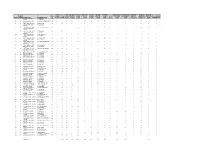

WILD FIRE INVASIVE AIR QUALITY EDUCATION OPP FOR REC SITE OUTFITTER ADEQUATE PLAN INFORMATION IM UPWARD IM NEEDS BASELINE FOREST WILD MANAGED TOTAL PLANS PLANTS VALUES PLANS SOLITUDE INVENTORY GUIDE NO OG STANDARDS MANAGEMENT REP DATA ASSESSMNT WORKFORCE IM VOLUNTEERS REGION NUMBER FOREST NAME WILDERNESS NAME ID TO STD? SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE FLAG SCORE SCORE COMPL FLAG COMPL FLAG SCORE USED EFF FLAG 02 02 BIGHORN NATIONAL CLOUD PEAK 080 Y 76 8 10 10 6 4 8 10 N 8 8 Y N 4 N FOREST WILDERNESS 02 03 BLACK HILLS NATIONAL BLACK ELK WILDERNESS 172 Y 84 10 10 4 10 10 10 10 N 8 8 Y N 4 N FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP FOSSIL RIDGE 416 N 59 6 5 2 6 8 8 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP LA GARITA WILDERNESS 032 Y 61 6 3 10 4 6 8 8 N 6 6 Y N 4 Y GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP LIZARD HEAD 040 N 47 6 3 2 4 6 4 6 N 6 8 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP MOUNT SNEFFELS 167 N 45 6 5 2 2 6 4 8 N 4 6 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP POWDERHORN 413 Y 62 6 6 2 6 8 10 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP RAGGEDS WILDERNESS 170 Y 62 0 6 10 6 6 10 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP UNCOMPAHGRE 037 N 45 6 5 2 2 6 4 8 N 4 6 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP WEST ELK WILDERNESS 039 N 56 0 6 10 6 6 4 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 06 MEDICINE BOW-ROUTT ENCAMPMENT RIVER 327 N 54 10 6 2 6 6 8 6 -

Page 1464 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1132

§ 1132 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 1464 Department and agency having jurisdiction of, and reports submitted to Congress regard- thereover immediately before its inclusion in ing pending additions, eliminations, or modi- the National Wilderness Preservation System fications. Maps, legal descriptions, and regula- unless otherwise provided by Act of Congress. tions pertaining to wilderness areas within No appropriation shall be available for the pay- their respective jurisdictions also shall be ment of expenses or salaries for the administra- available to the public in the offices of re- tion of the National Wilderness Preservation gional foresters, national forest supervisors, System as a separate unit nor shall any appro- priations be available for additional personnel and forest rangers. stated as being required solely for the purpose of managing or administering areas solely because (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classi- they are included within the National Wilder- fications as primitive areas; Presidential rec- ness Preservation System. ommendations to Congress; approval of Con- (c) ‘‘Wilderness’’ defined gress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Ea- A wilderness, in contrast with those areas gles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado where man and his own works dominate the The Secretary of Agriculture shall, within ten landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where years after September 3, 1964, review, as to its the earth and its community of life are un- suitability or nonsuitability for preservation as trammeled by man, where man himself is a visi- wilderness, each area in the national forests tor who does not remain. An area of wilderness classified on September 3, 1964 by the Secretary is further defined to mean in this chapter an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its of Agriculture or the Chief of the Forest Service primeval character and influence, without per- as ‘‘primitive’’ and report his findings to the manent improvements or human habitation, President. -

Page 1517 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1131 (Pub. L

Page 1517 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1131 (Pub. L. 88–363, § 10, July 7, 1964, 78 Stat. 301.) Sec. 1132. Extent of System. § 1110. Liability 1133. Use of wilderness areas. 1134. State and private lands within wilderness (a) United States areas. The United States Government shall not be 1135. Gifts, bequests, and contributions. liable for any act or omission of the Commission 1136. Annual reports to Congress. or of any person employed by, or assigned or de- § 1131. National Wilderness Preservation System tailed to, the Commission. (a) Establishment; Congressional declaration of (b) Payment; exemption of property from attach- policy; wilderness areas; administration for ment, execution, etc. public use and enjoyment, protection, preser- Any liability of the Commission shall be met vation, and gathering and dissemination of from funds of the Commission to the extent that information; provisions for designation as it is not covered by insurance, or otherwise. wilderness areas Property belonging to the Commission shall be In order to assure that an increasing popu- exempt from attachment, execution, or other lation, accompanied by expanding settlement process for satisfaction of claims, debts, or judg- and growing mechanization, does not occupy ments. and modify all areas within the United States (c) Individual members of Commission and its possessions, leaving no lands designated No liability of the Commission shall be im- for preservation and protection in their natural puted to any member of the Commission solely condition, it is hereby declared to be the policy on the basis that he occupies the position of of the Congress to secure for the American peo- member of the Commission. -

Rocky Mountain Region 2 – Historical Geography, Names, Boundaries

NAMES, BOUNDARIES, AND MAPS: A RESOURCE FOR THE HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE NATIONAL FOREST SYSTEM OF THE UNITED STATES THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION (Region Two) By Peter L. Stark Brief excerpts of copyright material found herein may, under certain circumstances, be quoted verbatim for purposes such as criticism, news reporting, education, and research, without the need for permission from or payment to the copyright holder under 17 U.S.C § 107 of the United States copyright law. Copyright holder does ask that you reference the title of the essay and my name as the author in the event others may need to reach me for clarifi- cation, with questions, or to use more extensive portions of my reference work. Also, please contact me if you find any errors or have a map that has not been included in the cartobibliography ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In the process of compiling this work, I have met many dedicated cartographers, Forest Service staff, academic and public librarians, archivists, and entrepreneurs. I first would like to acknowledge the gracious assistance of Bob Malcolm Super- visory Cartographer of Region 2 in Golden, Colorado who opened up the Region’s archive of maps and atlases to me in November of 2005. Also, I am indebted to long-time map librarians Christopher Thiry, Janet Collins, Donna Koepp, and Stanley Stevens for their early encouragement and consistent support of this project. In the fall of 2013, I was awarded a fellowship by The Pinchot Institute for Conservation and the Grey Towers National Historic Site. The Scholar in Resi- dence program of the Grey Towers Heritage Association allowed me time to write and edit my research on the mapping of the National Forest System in an office in Gifford Pinchot’s ancestral home. -

North Platte River Basin Wetland Profile and Condition Assessment

North Platte River Basin Wetland Profile and Condition Assessment March 31, 2012 Colorado Natural Heritage Program Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 North Platte River Basin Wetland Profile and Condition Assessment Prepared for: Colorado Parks and Wildlife Wetland Wildlife Conservation Program 317 West Prospect Fort Collins, CO 80526 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 8 1595 Wynkoop Street Denver, CO 80202 Prepared by: Joanna Lemly and Laurie Gilligan Colorado Natural Heritage Program Warner College of Natural Resources Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 In collaboration with Brian Sullivan, Grant Wilcox, and Jon Runge Colorado Parks and Wildlife Dr. Jennifer Hoeting and Erin Schliep Department of Statistics, Colorado State University Cover photographs: All photos taken by Colorado Natural Heritage Program Staff. Copyright © 2012 Colorado State University Colorado Natural Heritage Program All Rights Reserved EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The North Platte River Basin covers >2,000 square miles in north central Colorado and is known for extensive wetland resources. Of particular importance to Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW), the basin’s wetlands serve as significant waterfowl breeding areas and refuge for rare amphibians, fish, and invertebrates. Recognizing the need for better information about wetlands across the state, CPW and Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP) began a collaborative effort called Statewide Strategies for Colorado Wetlands to catalogue the location, type, and condition of Colorado’s wetlands through a series of river basin-scale wetland profile and condition assessment projects. This report summarizes finding from the second basinwide wetland condition assessment, conducted in the North Platte River Basin. The initial step in each project is to compile a “wetland profile” based on digital wetland mapping. -

Page 1480 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1113 (Pub

§ 1113 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 1480 (Pub. L. 88–363, § 13, July 7, 1964, 78 Stat. 301.) ment of expenses or salaries for the administra- tion of the National Wilderness Preservation § 1113. Authorization of appropriations System as a separate unit nor shall any appro- There are hereby authorized to be appro- priations be available for additional personnel priated to the Department of the Interior with- stated as being required solely for the purpose of out fiscal year limitation such sums as may be managing or administering areas solely because necessary for the purposes of this chapter and they are included within the National Wilder- the agreement with the Government of Canada ness Preservation System. signed January 22, 1964, article 11 of which pro- (c) ‘‘Wilderness’’ defined vides that the Governments of the United States A wilderness, in contrast with those areas and Canada shall share equally the costs of de- where man and his own works dominate the veloping and the annual cost of operating and landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where maintaining the Roosevelt Campobello Inter- the earth and its community of life are un- national Park. trammeled by man, where man himself is a visi- (Pub. L. 88–363, § 14, July 7, 1964, 78 Stat. 301.) tor who does not remain. An area of wilderness is further defined to mean in this chapter an CHAPTER 23—NATIONAL WILDERNESS area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its PRESERVATION SYSTEM primeval character and influence, without per- manent improvements or human habitation, Sec. which is protected and managed so as to pre- 1131. -

Colorado Native Plant Society "

• uze• za Newsletter of tbe Colorado Native Plant Society " ... dedicated to the appreciation and conservation of the Coloraqo native flora" ·V(jIUro¢>20· •••• ••· •• Nprnbgt· •• 1 Botanical Notes from the Arkansas Valley II: the Ecology of Oxybaphus rotundifolius Tass Kelso, Kirsten Heckmann, Reproduction exclosures equaling seed set in open polli John Lawton, and George Maentz In general, Oxybaphus rotundifolius popu nated plants. However, seed predation by Dept. of Biology, Colorado College lations had an excellent year, probably due ·insects may be responsible for relativel y low in. part to an unusually wet spring. Plants actual reproductive success: we found ant Increasing concern about developm~nt in bloomed abundantly from early June thieves making off with seeds on a frequent ~he Arkansas River Valley and its potential through late July, with peak bloom in late basis! We also documented extensive her impacts on local biota has brought much June. bivory of leaves and inflorescences by needed attention to the botany of this region._ hornworms. Reared hornworm specimens Thanks to funding provided by the Colorado Umbrella-wort flowers open at dawn and pupated and emerged as white-lined Sphinx Natural Areas Program and the Colorado close in response to temperature: on cool moths, Hyles lineata.. Positive insect inter Native PIIDl:t Society, this summer we were cloudy days they can remain open into the actions were also noted: we captured able to examine closely some of the endemic late afternoon, but on hot sunny days they pollinators' of several types ranging· from calciphiles of the Middle Arkansas with the close by 9:30 or 10:00 a.m. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………….….....i Boulder Ranger District………….…47 Redfeather Ranger District…..…196 (Currently, northern part of Canyon Lakes RD) Boulder Creeks Cameron Pass CHAPTER ONE Brainard Cherokee Park Forestwide Direction Caribou Deadman Indian Peaks Wilderness Elkhorn James Creek Section One – Forestwide Greyrock James Peak Goals and Objectives………….....1 Laramie River Valley Lump Gulch Lone Pine Mammoth Neota Wilderness Middle St. Vrain Section Two –Operational Rawah Wilderness Niwot Ridge Goals, Standards, and Redfeather North St. Vrain Guidelines…………..……11 Roach Sugarloaf Sheep Creek Thorodin Part 1 – Physical Resources…….…13 Williams Gulch Air Water Resources Minerals/Energy Clear Creek Ranger District…..….108 Sulphur Ranger District.……..…260 Arapaho Nat. Rec. Area Part 2 – Biological Resources…......16 Berthoud Pass Bowen Biodiversity Chicago Creek Broken Rack Silviculture/Timber Evergreen Buffalo Grazing Management Loveland Pass Cabin Creek Wildlife Mount Evans Crooked Creek Yankee Hill Elk Creek Part 3 – Disturbance Processes…….32 Fraser Experimental Forest Fire Little Gravel Insect and Disease Estes-Poudre Ranger District...…..139 Never Summer Wilderness Undesirable Species (Currently, southern part of Canyon Lakes RD) Parkca Buckhorn Ranch Creek Part 4 –Managing for Rec. Users….33 Cache la Poudre Wilderness Stillwater Dispersed Recreation Cedar Park Tabernash Developed Recreation Comanche Peak Wilderness Vasquez Wilderness Scenery Management Crosier Winter Park Crown Point Part 5 – Administration……………37 Elk Ridge CHAPTER THREE Real Estate Lion Gulch Management Area Direction……323 Special Uses Pingree Infrastructure Poudre Canyon Poverty CHAPTER FOUR Monitoring and Evaluation……...387 CHAPTER TWO Geographic Area Direction……….41 Pawnee National Grassland…..…..190 SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE..……397 . -

The Wilderness Act of 1964

The Wilderness Act of 1964 Source: US House of Representatives Office of the Law This is the 1964 act that started it all Revision Counsel website at and created the first designated http://uscode.house.gov/download/ascii.shtml wilderness in the US and Nevada. This version, updated January 2, 2006, includes a list of all wilderness designated before that date. The list does not mention designations made by the December 2006 White Pine County bill. -CITE- 16 USC CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM 01/02/2006 -EXPCITE- TITLE 16 - CONSERVATION CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -HEAD- CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -MISC1- Sec. 1131. National Wilderness Preservation System. (a) Establishment; Congressional declaration of policy; wilderness areas; administration for public use and enjoyment, protection, preservation, and gathering and dissemination of information; provisions for designation as wilderness areas. (b) Management of area included in System; appropriations. (c) "Wilderness" defined. 1132. Extent of System. (a) Designation of wilderness areas; filing of maps and descriptions with Congressional committees; correction of errors; public records; availability of records in regional offices. (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classifications as primitive areas; Presidential recommendations to Congress; approval of Congress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Eagles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado. (c) Review by Secretary of the Interior of roadless areas of national park system and national wildlife refuges and game ranges and suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; authority of Secretary of the Interior to maintain roadless areas in national park system unaffected. (d) Conditions precedent to administrative recommendations of suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; publication in Federal Register; public hearings; views of State, county, and Federal officials; submission of views to Congress. -

Mineral Resource Potential of National Forest RARE II and Wilderness Areas in Colorado

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mineral resource potential of National Forest RARE II and wilderness areas in Colorado Compiled By Robert P. Dickerson 1 Open-File Report 86-0364 1986 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Denver, Colorado CONTENTS (See also indices listings, p. 173) Page Introduction..................................................... 1 Grand Mesa, Gunnison, and Uncompahgre National Forests........... 2 Elk Mountains-Collegiate (2-180)............................ 2 Collegiate Peaks Wilderness (NF-180)........................ 2 Elk Mountains-Collegiate (2-180)............................ 5 Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness (NF-047)................... 5 Oh-Be-Joyful (2-181)........................................ 6 Ragged Mountain Wilderness (NF-181)......................... 7 Raggeds (2-181)............................................. 7 Drift Creek (2-182).......................................... 9 Perham Creek (2-183)........................................ 9 Springhouse Park (2-184).................................... 10 Electric Mountain (2-185)................................... 10 Clear Creek (2-186)......................................... 11 Hightower (2-189)........................................... 12 Priest Mountain (2-191)..................................... 12 Salt Creek (2-192).......................................... 12 Battlement Mesa (2-193)....................................