The Contemporary Relevance of Split Portraiture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern & Contemporary African

X Modern & Contemporary African Art 14 February 2020 Cape Town, South Africa An auction co-curated by X Modern & Contemporary African Art Afternoon Sale | Vente de l’Après-Midi Public auction hosted by Aspire Art Auctions & PIASA Vente aux enchères publiques co-dirigée par Aspire Art Auctions & PIASA VIEWING AND AUCTION LOCATION | LIEU DE L’EXPOSITION ET DE LA VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES OroAfrica House | 170 Buitengracht Street | Cape Town | South Africa AUCTION | VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES Friday 14 February at 3 pm | Vendredi 14 Février à 15H PUBLIC OPENING | VERNISSAGE Tuesday 11 February at 6 – 8:30 pm | Mardi 11 Février 18H – 20H30 PUBLIC PREVIEW | EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES Wednesday 12 February 12 pm – 5 pm | Mercredi 12 Février 12H – 17H Thursday 13 February 10 am – 5 pm | Jeudi 13 Février 10H – 17H Friday 14 February 10 am – 3 pm | Vendredi 14 Février 10H – 15H CONDITIONS OF SALE | CONDITIONS GÉNÉRALES DE VENTE The auction is subject to: Rules of Auction, Important Notices, Conditions of Business and Reserves La vente aux enchères est régie par les textes suivants : Règles de ventes, Remarques importantes, Conditions Générales de ventes et Réserves ABSENTEE AND TELEPHONE BIDS | ORDRES D’ACHAT ET ENCHÈRES PAR TÉLÉPHONE [email protected] | +27 71 675 2991 (South Africa) | +33 6 22 31 37 87 (France) GENERAL ENQUIRIES | INFORMATIONS JHB | [email protected] | +27 11 243 5243 CT | [email protected] | +27 21 418 0765 PARIS | [email protected] | [email protected] | +33 6 22 31 3787 Aspire Company Reg No: 2016/074025/07 | VAT number: 4100 275 280 i INTRODUCTION FROM ASPIRE There has been phenomenal growth of global interest in the art produced on the African continent. -

Uneasy Bodies, Femininity and Death: Representing the Female Corpse in Fashion Photography and Selected Contemporary Artworks

Uneasy bodies, femininity and death: Representing the female corpse in fashion photography and selected contemporary artworks. by Thelma van Rensburg 88270442 Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for MASTERS OF ARTS degree in FINE ARTS In the DEPARTMENT OF VISUAL ARTS FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: Dr Johan Thom August 2016 © University of Pretoria THELMA VAN RENSBURG ABSTRACT This mini-dissertation serves as a framework for my own creative practice. In this research paper my intention is to explore, within a feminist reading, representations of the female corpse in fashion photography and art. The cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s theories on the concept of representation are utilised to critically analyse and interogate selected images from fashion magazines, which depicts the female corpse in an idealised way. Such idealisation manifests in Western culture, in fashion magazines, as expressed in depictions of the attractive/ seductive/fine-looking female corpse. Fashion photographs that fit this description are critically contrasted and challenged to selected artworks by Penny Siopis and Marlene Dumas, alongside my own work, to explore how the female corpse can be represented, as strategy to undermine the aesthetic and cultural objectification of the female body. Here the study also explores the selected artists’ utilisation of the abject and the grotesque in relation to their use of artistic mediums and modes of production as an attempt to create ambiguous and conflicting combinations of attraction and repulsion (the sublime aesthetic of delightful horror), thereby confronting the viewer with the notion of the objectification of the decease[d] feminine body as object to-be-looked-at. -

The 80S: a Topology Approx $81

ART The 80s: A Topology approx $81 The 80s: A Topology Fundação de Serralves. Porto 2006 While the debate on whether the 1980s are best left forgotten continues, this catalogue (in nothing less than a neon pink cover) documents an extensive exhibition curated by Ulrich Loock – which evaluates the artistic output and development of that period. Featuring 80 artists and more than 100 works, all generously documented, the catalogue also contains essays, interviews and an extensive chronology detailing the highlights of each year. 428 p ills colour & b/w 23 x 29 English pb Idea Code 06510 ISBN 978 972 739 169 1 World rights except Portugal Art Art Futura 2006: Data Aesthetics approx $35 Art Futura 2006: Data Aesthetics Art Futura, Barcelona 2006 Catalogue accompanying the 17th edition of the Art Futura festival which documents the most outstanding and innovative projects on the international scene of digital art, interactive design, computer animation and video games. Participants featured this year included: Aardman, A Scanner Darkly, UVA, Realities:United, Heebok Lee and Nobuo Takahashi. 80 p + DVD colour & b/w Spanish/English pb Idea Code 06536 ISBN 84 922084 9 X World rights except Spain Art/Various Art in America approx $58 Art in America Arario, Cheonan 2006 Exhibition catalogue from a show held at Arario Gallery which introduced seven young American artists to the Korean public in a spirit similar to that which surrounded the arrival of the ‘Young British Artists’ and the ‘New Leipzig School’. The seven artists featured are: Christopher Deaton, Roe Ethridge, Rob Fischer, Euan Macdonald, Todd Norsten, Allison Smith and Leo Villareal. -

Marlene Dumas - the New York Times 28/09/2017, 16�52

Marlene Dumas - The New York Times 28/09/2017, 1652 T MAGAZINE Marlene Dumas By CLAIRE MESSUD AUG. 20, 2014 One of the most provocative painters of the human form, the South African– born artist Marlene Dumas doesn’t match the stereotype of artist as solitary genius. Her way is chaotic, more responsive and uncertain — and that is her brilliance. One measure of genius is the life force — what Harold Bloom has dubbed, referring to Samuel Johnson, “Falstaffian vitalism.” The South African-born artist Marlene Dumas has such astonishing vitality. On the occasion of our recent meeting in Amsterdam, she gave me her full, intense attention for the better part of nine hours and several bottles of wine between us (“I always think some wine is nice, don’t you?”) before bundling me into a taxi to my hotel, while she calmly strolled back to her studio in the midsummer twilight for a couple more hours of hard work. Her airy office and studio are shaded by leafy vines on the ground floor of an apartment block in a residential neighborhood to the south of the city center. On the corner are a Turkish greengrocer — as I passed, the owner impressively halved a watermelon with a machete — and a modest beauty salon obscured by dusty windows. So warm was her welcome that I almost remember her hugging me (she didn’t). In her rapid, digressive speech punctuated by laughter and tinged with an Afrikaans accent — she often interjects “nee” or “and so” — she offered me an early aperitif and we sat down to chat for what was supposed to be a few minutes before heading over the road for lunch in a local cafe. -

SADEQUAIN in PARIS 1961–1967 Grosvenor Gallery

GrosvenorGrosvenor Gallery Gallery SADEQUAINSADEQUAIN ININ PARIS PARIS 1961–19671961–1967 Grosvenor Gallery SADEQUAIN IN PARIS 1961–1967 Grosvenor Gallery SADEQUAIN IN PARIS 1961–1967 Cover Sadequain’s illustration for Albert Camus’ L’Étranger (detail) Lithograph on vélin de Rives paper 32.5 x 50.5 cm. (12 3/4 x 19 7/8 in.) Inside cover The Webbed XIX Pen and ink on paper Signed and dated ‘5.5.66’ lower left 50 x 71 cm. (19 11/16 x 27 15/16 in.) Grosvenor Gallery SADEQUAIN IN PARIS 1961–1967 5 November–14 November 2015 Syed Ahmed Sadequain Naqqash was arguably one of the most important South Asian artists of the 20th century. Sadequain was born in Amroha, today’s India, in 1930 to an educated North Indian Shia family, to which calligraphy was a highly valued skill. Following his education between Amroha and Agra and after a number of years working at various radio stations in Delhi and Karachi as a calligrapher- copyist, he began to dedicate more time to his artistic practices. In 1955 he exhibited a number of paintings at the residence of Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, a liberal patron of the arts. Soon after this, he received a number of important governmental commissions for municipal murals, which led to a number of solo exhibitions in Pakistan. In 1960 Sadequain won the Pakistan National prize for painting, and was invited by the French Committee of the International Association of Plastic Arts to visit Paris. The following few years were to be some of the most important for the young artist in terms of his artistic development, and it was whilst in Paris that he began to achieve international critical acclaim. -

1 ) Mbongeni Buthelezi * 2) Mia Chaplin * 3) Francina Dhimandi * 4

Galerie Patries van Dorst LIST OF PARTCIPATING ARTISTS SOUTH AFRICAN ART EXHIBITION MAY 1-MAY 20, 2016 GALERIE PATRIES VAN DORST, WASSENAAR CURATORS: PATRIES VAN DORST, ANNEMIEKE DE KLER The published information is subject to typing errors, price errors and availability. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 ) Mbongeni Buthelezi * 2) Mia Chaplin * 3) Francina Dhimandi * 4) Fortune Dlamini * 5) Marlene Dumas * 6) Jon Eiselin * 7) Ruan Hoffmann * 10) Themba Khumalo * 11) Esther Mahlangu * 12) Sara-J * 13) Lehlogonolo Mashaba * 14) Ira van der Merwe * 15) Samson Mnisi * 16) Francois de Plessis * 17) Gavin Rain * 18) Heidi Sincuba * 19) Michele Tabor * 20) Adriaan de Villiers * 21) Neo Matloga 1 1. Mbongeni Buthelezi (in cooperation with Tse Tse Gallery, Gent) Mbongeni Buthelezi grew up in Soweto, Johannesburg and studied at Funda Art School, Soweto. In the streets of Soweto a lot of plastic packing material could be found. This gave him the inspiration to work with plastic. He treats the different types of plastic with a hit gun to stick the and stiffen this material on a surface. In this way he created colorful paintings with a very lively texture. His arts works are both abstract and figurative. Buthelezi’s unique skills make his work increasingly aroused interest even outside South Africa. He exhibited in Amsterdam, Cologne, London, Madeira, New York, Gent, Vienna and others. Recently he started making beautiful drawings on paper. Singing the blues 43cm x 55 cm 2005 Plastic on plastic, € 1.600,= The trumpeter 40 cm x 55 cm 2005 Plastic on plastic, € 1.600,= 2 Poet 40 cm x 55 cm 2005 Plastic on plastic, € 1.600,= 2. -

M O MA Highligh Ts M O MA Highligh Ts

MoMA Highlights MoMA Highlights MoMA This revised and redesigned edition of MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from The Museum of Modern Art presents a new selection from the Museum’s unparalleled collection of modern and contemporary art. Each work receives a vibrant image and an informative text, and 115 works make their first appearance in Highlights, many of them recent acquisitions reflecting the Museum’s commitment to the art of our time. 350 Works from The Museum of Modern Art New York MoMA Highlights 350 Works from The Museum of Modern Art, New York The Museum of Modern Art, New York 2 3 Introduction Generous support for this publication is Produced by the Department of Publications What is The Museum of Modern Art? 53rd Street, from a single curatorial The Museum of Modern Art, New York provided by the Research and Scholarly At first glance, this seems like a rela- department to seven (including the Publications Program of The Museum of Edited by Harriet Schoenholz Bee, Cassandra Heliczer, tively straightforward question. But the most recently established one, Media Modern Art, which was initiated with the sup- and Sarah McFadden Designed by Katy Homans answer is neither simple nor straight- and Performance Art, founded in port of a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Production by Matthew Pimm forward, and any attempt to answer it 2006), and from a program without a Foundation. Publication is made possible Color separations by Evergreen Colour Separation permanent collection to a collection of by an endowment fund established by The (International) Co., Ltd., Hong Kong almost immediately reveals a complex Printed in China by OGI/1010 Printing International Ltd. -

FY2009 Annual Listing

2008 2009 Annual Listing Exhibitions PUBLICATIONS Acquisitions GIFTS TO THE ANNUAL FUND Membership SPECIAL PROJECTS Donors to the Collection 2008 2009 Exhibitions at MoMA Installation view of Pipilotti Rist’s Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters) at The Museum of Modern Art, 2008. Courtesy the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Hauser & Wirth Zürich London. Photo © Frederick Charles, fcharles.com Exhibitions at MoMA Book/Shelf Bernd and Hilla Becher: Home Delivery: Fabricating the Through July 7, 2008 Landscape/Typology Modern Dwelling Organized by Christophe Cherix, Through August 25, 2008 July 20–October 20, 2008 Curator, Department of Prints Organized by Peter Galassi, Chief Organized by Barry Bergdoll, The and Illustrated Books. Curator of Photography. Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design, and Peter Glossolalia: Languages of Drawing Dalí: Painting and Film Christensen, Curatorial Assistant, Through July 7, 2008 Through September 15, 2008 Department of Architecture and Organized by Connie Butler, Organized by Jodi Hauptman, Design. The Robert Lehman Foundation Curator, Department of Drawings. Chief Curator of Drawings. Young Architects Program 2008 Jazz Score July 20–October 20, 2008 Multiplex: Directions in Art, Through September 17, 2008 Organized by Andres Lepik, Curator, 1970 to Now Organized by Ron Magliozzi, Department of Architecture and Through July 28, 2008 Assistant Curator, and Joshua Design. Organized by Deborah Wye, Siegel, Associate Curator, The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Department of Film. Dreamland: Architectural Chief Curator of Prints and Experiments since the 1970s Illustrated Books. George Lois: The Esquire Covers July 23, 2008–March 16, 2009 Through March 31, 2009 Organized by Andres Lepik, Curator, Projects 87: Sigalit Landau Organized by Christian Larsen, Department of Architecture and Through July 28, 2008 Curatorial Assistant, Research Design. -

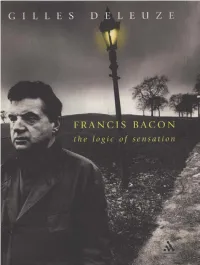

Francis Bacon: the Logic of Sensation

Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation GILLES DELEUZE Translated from the French by Daniel W. Smith continuum LONDON • NEW YORK This work is published with the support of the French Ministry of Culture Centre National du Livre. Liberte • Egalite • Fraternite REPUBLIQUE FRANCAISE This book is supported by the French Ministry for Foreign Affairs, as part of the Burgess programme headed for the French Embassy in London by the Institut Francais du Royaume-Uni. Continuum The Tower Building 370 Lexington Avenue 11 York Road New York, NY London, SE1 7NX 10017-6503 www.continuumbooks.com First published in France, 1981, by Editions de la Difference © Editions du Seuil, 2002, Francis Bacon: Logique de la Sensation This English translation © Continuum 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Gataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library ISBN 0-8264-6647-8 Typeset by BookEns Ltd., Royston, Herts. Printed by MPG Books Ltd., Bodmin, Cornwall Contents Translator's Preface, by Daniel W. Smith vii Preface to the French Edition, by Alain Badiou and Barbara Cassin viii Author's Foreword ix Author's Preface to the English Edition x 1. The Round Area, the Ring 1 The round area and its analogues Distinction between the Figure and the figurative The fact The question of "matters of fact" The three elements of painting: structure, Figure, and contour - Role of the fields 2. -

Bacon, Francis (1909-1992) by Andres Mario Zervigon

Bacon, Francis (1909-1992) by Andres Mario Zervigon Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Fancis Bacon is widely recognized as Britain's most important twentieth-century painter. Through beautifully composed works featuring screaming faces and beaten bodies, Bacon marked the violent trauma characterizing Europe's past century. On this basis his painting was celebrated in Britain's post-World War II society. As well as reflecting a universal preoccupation with violence, however, Bacon's paintings draw from the artist's own fascination with gay male masochism and the manner with which such desire can be represented. An openly gay man who refused to censor his art, Bacon produced one of the few bodies of work characterized by radical sexuality, yet praised by a broad and largely conservative art public. Bacon was born on October 28, 1909 in Dublin, Ireland, the son of a British horse breeder and trainer. He passed a relatively happy youth disturbed only by the outbreak of Ireland's civil war, a conflict in which Irish rebels perceived all English, including Bacon's family, as the enemy. He later claimed that this experience initiated his fascination with violence. At the age of sixteen in 1927, Bacon was evicted from his family home for sleeping with his father's horse grooms. Bag in hand, he resolved to travel in Europe. After nearly two years in Paris and Berlin, Bacon eventually settled in London, where he realized his plans to become a furniture and interior designer. He quickly found success in 1930 with his widely published, Bauhaus-inspired interiors. -

2012Wolfgang Tillmans Zachęta Ermutigung

Zachęta — National Gallery of Art ANNUAL REPORT Wolfgang Tillmans Zachęta Ermutigung — Hypertext. 10 Years of Centrala (Kordegarda Project) 2012— Goshka Macuga. Untitled — No, No, I Hardly Ever Miss a Show — Warsaw ENcourages (Art Gallery at the Warsaw Chopin Airport) — Karolina Freino. Erase Boards (Kordegarda Project) — Rafał Milach. 7 Rooms — Doubly Regained Territories. Bogdan Łopieński, Andrzej Tobis, Krzysztof Żwirblis — New Sculpture? — On a Journey (Art Gallery at the Warsaw Chopin Airport) — Emotikon. Robert Rumas & Piotr Wyrzykowski — Małgorzata Jabłońska, Piotr Szewczyk. Dzikie ∫ Wild (ZPR) — Art Everywhere. The Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw 1904–1944 — Konrad Maciejewicz. Transform Me (ZPR) — Jaśmina Wójcik. Hiding People among People without Contact with Nature Leads to Perversions (ZPR) — Making the walls quake as if they were dilating with the secret knowledge of great powers (13th International Architecture Exhibition, Polish Pavilion, Venice) — Beyond Corrupted Eye. Akumulatory 2 Gallery, 1972–1990 — HOOLS — Marlene Dumas. Love Hasn’t Got Anything to Do with It — Katarzyna Kozyra. Master of Puppets (Schmela Haus — Kunstsammlung Nordrhein- Westfalen, Düsseldorf) — Izabella Jagiełło. A Beast (ZPR) — Anna Molska. The Sixth Continent — Piotr Uklański. Czterdzieści i cztery — Marek Konieczny. Think Crazy — Jarosław Jeschke. Hamlet Lavastida. Jose Eduardo Yaque Llorente. Fragmentos (ZPR) Zachęta — National Gallery of Art ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Warsaw 2013 ZACHĘTA GALLERY Renovation of the space of the new library 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Photo by Sebastian Madejski by Photo CONTENTS Changes, changes, changes . 5 HANNA WRÓBLEWSKA AND THE ZACHĘTA TEAM GALLERY STRUCTURE 8 Directors and the Staff of the Zachęta in 2012 EXHIBITIONS 10 VISITOR NUMBERS 83 OTHER EVENTS 84 REVIEWS 88 ACTIVITY 98 Education Collection Documentation and Library Promotion Open Zachęta Editing Department Art Bookshop Development ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE ZACHĘTA TEAM 110 INCOME 115 PARTNERS AND SPONSORS 118 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Changes, changes, changes . -

ART CRITICISM I I, I

---~ - --------c---~ , :·f' , VOL. 14, No.2 ART CRITICISM i I, I ,\ Art Criticism vol. 14, no. 2 Art Department State University of New York at Stony Brook Stony Brook, NY 11794-5400 The editor wishes to thank Jamali and Art and Peace, Inc., The Stony . Brook Foundation, President Shirley Strumm Kenny, Provost Rollin C. Richmond, the Dean ofHumaniti~s and Fine Arts, Paul Armstrong, for their gracious support. Copyright 1999 State University of New York at Stony Brook ISSN: 0195-4148 2 Art Criticism Table of Contents Abstract Painting in the '90s 4 Mary Lou Cohalan and William V. Ganis Figurative Painting in the '90s 21 Jason Godeke, Nathan Japel, Sandra Skurvidaite Pitching Charrettes: Architectural Experimentation in the '90s 34 Brian Winkenweder From Corporeal Bodies to Mechanical Machines: 53 Navigating the Spectacle of American Installation in the '90s Lynn Somers with Bluewater Avery and Jason Paradis Video Art in the '90s 74 Katherine Carl, Stewart Kendall, and Kirsten Swenson Trends in Computer and Technological Art 94 Kristen Brown and Nina Salvatore This issue ofArt Criticism presents an overview ofart practice in the 1990s and results from a special seminar taught by Donald B. Kuspit in the fall of 1997. The contributors are current and former graduate students in the Art History and Criticism and Studio Art programs at Stony Brook. vol. 14, no. 2 3 Abstract Painting in the '90s by Mary Lou Cohalan and William V. Ganis Introduction In a postmodem era characterized by diversity and spectacle, abstract painting is just one of many fonnal strategies in the visual art world.