M O MA Highligh Ts M O MA Highligh Ts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kids Are Always Right Helen Molesworth on the Reinstallation of Moma’S Permanent Collection

TABLE OF CONTENTS PRINT JANUARY 2020 THE KIDS ARE ALWAYS RIGHT HELEN MOLESWORTH ON THE REINSTALLATION OF MOMA’S PERMANENT COLLECTION View of “Hardware/Software,” 2019–, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Foreground, from left: Joan Semmel, Night Light, 1978; Maren Hassinger, Leaning, 1980; Senga Nengudi, R.S.V.P. I, 1977/2003. Background: Cady Noland, Tanya as Bandit, 1989. Photo: John Wronn. THE VIBE started to trickle out via Instagram. For a few days, my feed was inundated with pictures of all the cool new shit on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. You could smell victory in the air: The artists were happy. Then the New York Times weighed in and touched the wide shoulders of the new, bigger-is-better MoMA with their magic wand. Could it be? Had MoMA, the perennial whipping boy of art historians, radical artists, and cranky art critics, gotten it right? And by right, at this moment, we mean that the collection has been installed with an eye toward inclusivity—of medium, of gender, of nationality, of ethnicity—and that modernism is no longer portrayed as a single, triumphant narrative, but rather as a network of contemporaneous and uneven developments. Right means that the curatorial efforts to dig deep into MoMA’s astounding holdings looked past the iconic and familiar (read: largely white and male). Right means that the culture wars, somehow, paid off. Right means that MoMA has finally absorbed the critiques of the past three decades—from the critical tear-down of former chief curator of painting and sculpture Kirk Varnedoe’s 1990 show “High and Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture” to the revisionist aspirations of former chief curator of drawings Connie Butler’s “Modern Women” project (2005–). -

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series Editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University Signale: Modern German Letters, Cultures, and Thought publishes new English- language books in literary studies, criticism, cultural studies, and intellectual history pertaining to the German-speaking world, as well as translations of im- portant German-language works. Signale construes “modern” in the broadest terms: the series covers topics ranging from the early modern period to the present. Signale books are published under a joint imprint of Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library in electronic and print formats. Please see http://signale.cornell.edu/. The Total Work of Art in European Modernism David Roberts A Signale Book Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Ithaca, New York Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library gratefully acknowledge the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the publication of this volume. Copyright © 2011 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writ- ing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2011 by Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roberts, David, 1937– The total work of art in European modernism / David Roberts. p. cm. — (Signale : modern German letters, cultures, and thought) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5023-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Modernism (Aesthetics) 2. -

Perceptions on the Starry Night

Kay Sohini Kumar To the Stars and Beyond: Perceptions on The Starry Night “The earliest experience of art must have been that it was incantatory, magical; art was an instrument of ritual. The earliest theory of art, that of Greek philosophers, proposed that art was mimesis, imitation of reality...even in the modern times, when most artists and critics have discarded the theory of art as representation of an outer reality in favor of theory of art as subjective expression, the main feature of the mimetic theory persists” (Sontag 3-4) What is it like to see the painting, in the flesh, that you have been worshipping and emulating for years? I somehow always assumed that it was bigger. The gilded frame enclosing The Starry Night at the Museum of Modern Art occupies less than a quarter of the wall it is hung upon. I had also assumed that there would be a bench from across the painting, where I could sit and gaze at the painting intently till I lost track of time and space. What I did not figure was how the painting would only occupy a tiny portion of the wall, or that there would be this many people1, that some of those people would stare at me strangely (albeit for a fraction of a second, or maybe I imagined it) for standing in front of The Starry Night awkwardly, with a notepad, scribbling away, for so long that it became conspicuous. I also did not expect how different the actual painting would be from the reproductions of it that I was used to. -

Citations 1. Arts and Crafts Period Style 1837-1901 2 Art Nouveau

1. Arts and Crafts Period Style 1837-1901 List Period Design Styles Page 1 of 2 pages The Arts and Crafts movement fostered a return to handcrafted individually. It included both artisans, architects and designers. “Ruskin rejected the mercantile economy and pointed toward the union of art and labor in service to society. .” 2 Alma-Tadema Edward Burne-Jones, Charles Rennie Mackintosh William Morris Dante Gabriel Rossetti 2 Art Nouveau 1880-1914 Art Nouveau is an international style of art, architecture and design that, like the Arts and Crafts movement, was reacting to the mechanical impact of the Industrial Revolution. “A style in art, manifested in painting, sculpture, printmaking, architecture, and decorative design . Among its principle characteristics were a cursive, expressive line with flowing, swelling reverse curves . Interlaced patterns, and the whiplash curve. In decoration, plant and flower motifs abounded..”1 Aubrey Beardsley Gustav Klimt Charles Rennie Mackintosh Louis Comfort Tiffany Peter Behrens Antoni Gaudi Hector Guimard 3 French Cubist & Italian Futurist Styles 1907-1920 Cubism and Futurism are early 20th Century revolutionary European art movements. In Analytical Cubism (the early Cubist style). objects were increasingly broken down and “analyzed” through such means as simultaneous rendition, the presentation of several aspects of an object at once.1 Futurism was aggressively dynamic, expressing movement and encompassing time as well as space; it was particularly concerned with mechanization and speed. French Cubist Artists Pablo Picasso (born Spain/lived in Paris, Fr) Georges Braque Italian Futurist Artists Giacomo Balla Umberto Boccioni Gino Severini 4 Bauhaus Style 1919-1933 Citations German school of architecture and industrial arts. -

Edrs Price Descriptors

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 224 EA 005 958 AUTHOR Kohl, Mary TITLE Guide to Selected Art Prints. Using Art Prints in Classrooms. INSTITUTION Oregon Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Salem. PUB DATE Mar 74 NOTE 43p.; Oregon'ASCD Curriculum Bulletin v28 n322 AVAILABLE FROMOregon Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, P.O. Box 421, Salem, Oregon 9730A, ($2.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.85 DESCRIPTORS *Art Appreciation; *Art Education; *Art Expression; Color Presentation; Elementary Schools; *Painting; Space; *Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS Texture ABSTRACT A sequential framework of study, that can be individually and creatively expanded, is provided for the purpose of developing in children understanding of and enjoyment in art. .The guide indicates routes of approach to certain kinds of major art, provides historical and biographical information, clarifies certain fundamentals of art, offers some activities related to the various ,elements, and conveys some continuing enthusiasm for the yonder of art creation. The elements of art--color, line, texture, shape, space, and forms of expression--provide the structure of pictorial organization. All of the pictures recomme ded are accessible tc teachers through illustrations in famil'a art books listed in the bibliography. (Author/MLF) US DEPARTMENT OF HE/ EDUCATION & WELFAS NATIONAL INSTITUTE I EOW:AT ION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEF DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIV e THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIO ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR STATED DO NOT NECESSAR IL SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INS1 EDUCATION POSIT100. OR POL Li Vi CD CO I IP GUIDE TO SELECTED ART PRINTS by Mary Kohl 1 INTRODUCTION TO GUIDE broaden and deepen his understanding and appreciation of art. -

Matisse Dance with Joy Ebook

MATISSE DANCE WITH JOY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Susan Goldman Rubin | 26 pages | 03 Jun 2008 | CHRONICLE BOOKS | 9780811862882 | English | San Francisco, United States Matisse Dance with Joy PDF Book Sell your art. Indeed, Matisse, with its use of strong colors and long, curved lines will initially influenced his acolytes Derain and Vlaminck, then expressionist and surrealist painters same. Jun 13, Mir rated it liked it Shelves: art. He starts using this practice since the title, 'Tonight at Noon' as it is impossible because noon can't ever be at night as it is during midday. Tags: h mastisse, matisse henri, matisse joy of life, matisse goldfish, matisse for kids, matisse drawing, drawings, artsy, matisse painting, henri matisse paintings, masterpiece, artist, abstract, matisse, famous, popular, vintage, expensive, henri matisse, womens, matisse artwork. Welcome back. Master's or higher degree. Matisse had a daughter with his model Caroline Joblau in and in he married Amelie Noelie Parayre with whom he raised Marguerite and their own two sons. Henri Matisse — La joie de vivre Essay. Tags: matisse, matisse henri, matisse art, matisse paintings, picasso, picasso matisse, matisse painting, henri matisse art, artist matisse, henri matisse, la danse, matisse blue, monet, mattise, matisse cut outs, matisse woman, van gogh, matisse moma, moma, henry matisse, matisse artwork, mattisse, henri matisse painting, matisse nude, matisse goldfish, dance, the dance, le bonheur de vivre, joy of life, the joy of life, matisse joy of life, bonheur de vivre, the joy of life matisse. When political protest is read as epidemic madness, religious ecstasy as nervous disease, and angular dance moves as dark and uncouth, the 'disorder' being described is choreomania. -

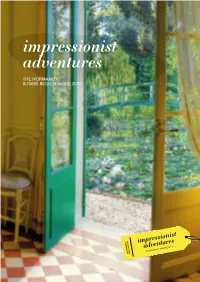

Impressionist Adventures

impressionist adventures THE NORMANDY & PARIS REGION GUIDE 2020 IMPRESSIONIST ADVENTURES, INSPIRING MOMENTS! elcome to Normandy and Paris Region! It is in these regions and nowhere else that you can admire marvellous Impressionist paintings W while also enjoying the instantaneous emotions that inspired their artists. It was here that the art movement that revolutionised the history of art came into being and blossomed. Enamoured of nature and the advances in modern life, the Impressionists set up their easels in forests and gardens along the rivers Seine and Oise, on the Norman coasts, and in the heart of Paris’s districts where modernity was at its height. These settings and landscapes, which for the most part remain unspoilt, still bear the stamp of the greatest Impressionist artists, their precursors and their heirs: Daubigny, Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Caillebotte, Sisley, Van Gogh, Luce and many others. Today these regions invite you on a series of Impressionist journeys on which to experience many joyous moments. Admire the changing sky and light as you gaze out to sea and recharge your batteries in the cool of a garden. Relive the artistic excitement of Paris and Montmartre and the authenticity of the period’s bohemian culture. Enjoy a certain Impressionist joie de vivre in company: a “déjeuner sur l’herbe” with family, or a glass of wine with friends on the banks of the Oise or at an open-air café on the Seine. Be moved by the beauty of the paintings that fill the museums and enter the private lives of the artists, exploring their gardens and homes-cum-studios. -

An Exhibition of Conceptual Art

THE MUSEUM OF ME (MoMe) An Exhibition of Conceptual Art by Heidi Ellis Overhill A thesis exhibition presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art East Campus Hall Gallery of the University of Waterloo April 13 to April 24, 2009 Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2009. ©Heidi Overhill 2009 i Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-54870-7 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-54870-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Modern & Contemporary African

X Modern & Contemporary African Art 14 February 2020 Cape Town, South Africa An auction co-curated by X Modern & Contemporary African Art Afternoon Sale | Vente de l’Après-Midi Public auction hosted by Aspire Art Auctions & PIASA Vente aux enchères publiques co-dirigée par Aspire Art Auctions & PIASA VIEWING AND AUCTION LOCATION | LIEU DE L’EXPOSITION ET DE LA VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES OroAfrica House | 170 Buitengracht Street | Cape Town | South Africa AUCTION | VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES Friday 14 February at 3 pm | Vendredi 14 Février à 15H PUBLIC OPENING | VERNISSAGE Tuesday 11 February at 6 – 8:30 pm | Mardi 11 Février 18H – 20H30 PUBLIC PREVIEW | EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES Wednesday 12 February 12 pm – 5 pm | Mercredi 12 Février 12H – 17H Thursday 13 February 10 am – 5 pm | Jeudi 13 Février 10H – 17H Friday 14 February 10 am – 3 pm | Vendredi 14 Février 10H – 15H CONDITIONS OF SALE | CONDITIONS GÉNÉRALES DE VENTE The auction is subject to: Rules of Auction, Important Notices, Conditions of Business and Reserves La vente aux enchères est régie par les textes suivants : Règles de ventes, Remarques importantes, Conditions Générales de ventes et Réserves ABSENTEE AND TELEPHONE BIDS | ORDRES D’ACHAT ET ENCHÈRES PAR TÉLÉPHONE [email protected] | +27 71 675 2991 (South Africa) | +33 6 22 31 37 87 (France) GENERAL ENQUIRIES | INFORMATIONS JHB | [email protected] | +27 11 243 5243 CT | [email protected] | +27 21 418 0765 PARIS | [email protected] | [email protected] | +33 6 22 31 3787 Aspire Company Reg No: 2016/074025/07 | VAT number: 4100 275 280 i INTRODUCTION FROM ASPIRE There has been phenomenal growth of global interest in the art produced on the African continent. -

Uneasy Bodies, Femininity and Death: Representing the Female Corpse in Fashion Photography and Selected Contemporary Artworks

Uneasy bodies, femininity and death: Representing the female corpse in fashion photography and selected contemporary artworks. by Thelma van Rensburg 88270442 Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for MASTERS OF ARTS degree in FINE ARTS In the DEPARTMENT OF VISUAL ARTS FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: Dr Johan Thom August 2016 © University of Pretoria THELMA VAN RENSBURG ABSTRACT This mini-dissertation serves as a framework for my own creative practice. In this research paper my intention is to explore, within a feminist reading, representations of the female corpse in fashion photography and art. The cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s theories on the concept of representation are utilised to critically analyse and interogate selected images from fashion magazines, which depicts the female corpse in an idealised way. Such idealisation manifests in Western culture, in fashion magazines, as expressed in depictions of the attractive/ seductive/fine-looking female corpse. Fashion photographs that fit this description are critically contrasted and challenged to selected artworks by Penny Siopis and Marlene Dumas, alongside my own work, to explore how the female corpse can be represented, as strategy to undermine the aesthetic and cultural objectification of the female body. Here the study also explores the selected artists’ utilisation of the abject and the grotesque in relation to their use of artistic mediums and modes of production as an attempt to create ambiguous and conflicting combinations of attraction and repulsion (the sublime aesthetic of delightful horror), thereby confronting the viewer with the notion of the objectification of the decease[d] feminine body as object to-be-looked-at. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Buchskulpturen – Zerstörung als produktives Schaffensmoment“ Verfasserin Constanze Anna Sabine Stahr angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 315 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Kunstgeschichte Betreuer: Dr. Sebastian Egenhofer „Ein Buch muss die Axt sein für das gefrorene Meer in uns.“ Franz Kafka Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides Statt, dass ich die vorliegende Diplomarbeit selbstständig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indirekt übernommenen Gedanken sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Wien, am 9.01.2013 Danksagung Ich möchte an dieser Stelle einigen Personen meinen Dank aussprechen, ohne deren Unterstützung die Erstellung dieser Diplomarbeit nur schwerlich möglich gewesen wäre. Auf fachlicher Seite danke ich vor allem Frau Prof. Dr. Julia Gelshorn und Herrn Dr. Sebastian Egenhofer für die Betreuung und maßgebliche Hilfe bei der Themenfindung. Für die Unterstützung in persönlicher und moralischer Art und Weise danke ich meiner Familie, besonders meinen Eltern, Dr. Ernst-Heinrich Stahr und Sabine Stahr, die mir das Studium erst ermöglichten und mir das Interesse für Kunst in die Wiege gelegt haben, sowie meiner Großmutter Josefa Henning und meinem Onkel Thomas Henning. Außerdem danke ich meinen -

Henri Matisse, Textile Artist by Susanna Marie Kuehl

HENRI MATISSE, TEXTILE ARTIST COSTUMES DESIGNED FOR THE BALLETS RUSSES PRODUCTION OF LE CHANT DU ROSSIGNOL, 1919–1920 Susanna Marie Kuehl Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art + Design 2011 ©2011 Susanna Marie Kuehl All Rights Reserved To Marie Muelle and the anonymous fabricators of Le Chant du Rossignol TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements . ii List of Figures . iv Chapter One: Introduction: The Costumes as Matisse’s ‘Best Spokesman . 1 Chapter Two: Where Matisse’s Art Meets Textiles, Dance, Music, and Theater . 15 Chapter Three: Expression through Color, Movement in a Line, and Abstraction as Decoration . 41 Chapter Four: Matisse’s Interpretation of the Orient . 65 Chapter Five: Conclusion: The Textile Continuum . 92 Appendices . 106 Notes . 113 Bibliography . 134 Figures . 142 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As in all scholarly projects, it is the work of not just one person, but the support of many. Just as Matisse created alongside Diaghilev, Stravinsky, Massine, and Muelle, there are numerous players that contributed to this thesis. First and foremost, I want to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Heidi Näsström Evans for her continual commitment to this project and her knowledgeable guidance from its conception to completion. Julia Burke, Textile Conservator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, was instrumental to gaining not only access to the costumes for observation and photography, but her energetic devotion and expertise in the subject of textiles within the realm of fine arts served as an immeasurable inspiration.