Doctoral Dissertation Nora Anna Escherle, M.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

1 All Rights Reserved Do Not Reproduce in Any Form Or

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DO NOT REPRODUCE IN ANY FORM OR QUOTE WITHOUT AUTHOR’S PERMISSION 1 2 Tactical Cities: Negotiating Violence in Karachi, Pakistan by Huma Yusuf A.B. English and American Literature and Language Harvard University, 2002 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © Huma Yusuf. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________________________________ Shankar Raman Associate Professor of Literature Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________________________________ William Charles Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies 3 4 Tactical Cities: Negotiating Violence in Karachi, Pakistan by Huma Yusuf Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in Science in Comparative Media Studies. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the relationship between violence and urbanity. Using Karachi, Pakistan, as a case study, it asks how violent cities are imagined and experienced by their residents. The thesis draws on a variety of theoretical and epistemological frameworks from urban studies to analyze the social and historical processes of urbanization that have led to the perception of Karachi as a city of violence. It then uses the distinction that Michel de Certeau draws between strategy and tactic in his seminal work The Practice of Everyday Life to analyze how Karachiites inhabit, imagine, and invent their city in the midst of – and in spite of – ongoing urban violence. -

Parliamentary Documentation

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIIIIIII (((111666 tttooo 333111 DDDeeeccceeemmmbbbeeerrr,,, 222000000777))) NNNooo... 222444 AGRICULTURE -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COCONUT 1 THAMBAN, C and others Economic analysis of coconut cultivation under micro-irrigation. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.425-430 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Coconut. -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 2 HABERBERGER, Marie Luise and RAMAKRISHNA Secure deposits of the poor. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2007(21.12.2007) Needs to review government's policy to reduce interest rate on agricultural loans. ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. 3 SARKAR, Keya Modes of micro-finance spending. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(26.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA-TAMIL NADU) 4 MAHENDRAN, R Study on temporal changes in Irrigated area and cropping pattern in Perambalur district of Tamil Nadu. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.439-444 ** Agriculture-Agricultural policy-(India-Tamil Nadu); Plantation. -AGRICULTURAL PRICES 5 GHOSH, Jayati Wheat price rise reflects government failure. DECCAN CHRONICLE, 2007(18.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Prices. -AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION 6 Agriculture GDP will grow at 3.2 to 3.6% in 2007-2008. MONTHLY COMMENTARY ON INDIAN ECONOMIC CONDITIONS, V.49(No.3), 2007 (October): P.8-12 ** Agriculture-Agricultural Production. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH 7 NIGADE, R.D Research and developments in small millets in Maharashtra. INDIAN FARMING, V.59(No.5), 2007(August): P.9-10 ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Crops. 8 SUD, Surinder Great new aroma. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(18.12.2007) Focuses on research done in Indian Agriculture Research Institute(IARI) for producing latest rice variety. ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Rice. -AGRICULTURAL TRADE 9 MISHRA, P.K Agricultural market reforms for the benefit of Farmers. -

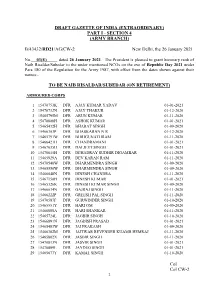

(PPMG) Police Medal for Gallantry (PMG) President's

Force Wise/State Wise list of Medal awardees to the Police Personnel on the occasion of Republic Day 2020 Si. Name of States/ President's Police Medal President's Police Medal No. Organization Police Medal for Gallantry Police Medal (PM) for for Gallantry (PMG) (PPM) for Meritorious (PPMG) Distinguished Service Service 1 Andhra Pradesh 00 00 02 15 2 Arunachal Pradesh 00 00 01 02 3 Assam 00 00 01 12 4 Bihar 00 07 03 10 5 Chhattisgarh 00 08 01 09 6 Delhi 00 12 02 17 7 Goa 00 00 01 01 8 Gujarat 00 00 02 17 9 Haryana 00 00 02 12 10 Himachal Pradesh 00 00 01 04 11 Jammu & Kashmir 03 105 02 16 12 Jharkhand 00 33 01 12 13 Karnataka 00 00 00 19 14 Kerala 00 00 00 10 15 Madhya Pradesh 00 00 04 17 16 Maharashtra 00 10 04 40 17 Manipur 00 02 01 07 18 Meghalaya 00 00 01 02 19 Mizoram 00 00 01 03 20 Nagaland 00 00 01 03 21 Odisha 00 16 02 11 22 Punjab 00 04 02 16 23 Rajasthan 00 00 02 16 24 Sikkim 00 00 00 01 25 Tamil Nadu 00 00 03 21 26 Telangana 00 00 01 12 27 Tripura 00 00 01 06 28 Uttar Pradesh 00 00 06 72 29 Uttarakhand 00 00 01 06 30 West Bengal 00 00 02 20 UTs 31 Andaman & 00 00 00 03 Nicobar Islands 32 Chandigarh 00 00 00 01 33 Dadra & Nagar 00 00 00 01 Haveli 34 Daman & Diu 00 00 00 00 02 35 Puducherry 00 00 00 CAPFs/Other Organizations 13 36 Assam Rifles 00 00 01 46 37 BSF 00 09 05 24 38 CISF 00 00 03 39 CRPF 01 75 06 56 12 40 ITBP 00 00 03 04 41 NSG 00 00 00 11 42 SSB 00 04 03 21 43 CBI 00 00 07 44 IB (MHA) 00 00 08 23 04 45 SPG 00 00 01 02 46 BPR&D 00 01 47 NCRB 00 00 00 04 48 NIA 00 00 01 01 49 SPV NPA 01 04 50 NDRF 00 00 00 00 51 LNJN NICFS 00 00 00 00 52 MHA proper 00 00 01 15 53 M/o Railways 00 01 02 (RPF) Total 04 286 93 657 LIST OF AWARDEES OF PRESIDENT'S POLICE MEDAL FOR GALLANTRY ON THE OCCASION OF REPUBLIC DAY-2020 President's Police Medal for Gallantry (PPMG) JAMMU & KASHMIR S/SHRI Sl No Name Rank Medal Awarded 1 Abdul Jabbar, IPS SSP PPMG 2 Gh. -

Toba Tek Singh Short Stories (Ii) the Dog of Tithwal

Black Ice Software LLC Demo version WELCOME MESSAGE Welcome to PG English Semester IV! The basic objective of this course, that is, 415 is to familiarize the learners with literary achievements of some of the significant Indian Writers whose works are available in English Translation. The course acquaints you with modern movements in Indian thought to appreciate the treatment of different themes and styles in the genres of short story, fiction, poetry and drama as reflected in the prescribed translations. You are advised to consult the books in the library for preparation of Internal Assessment Assignments and preparation for semester end examination. Wish you good luck and success! Prof. Anupama Vohra PG English Coordinator 1 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version 2 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version SYLLABUS M.A. ENGLISH Course Code : ENG 415 Duration of Examination : 3 Hrs Title : Indian Writing in English Total Marks : 100 Translation Theory Examination : 80 Interal Assessment : 20 Objective : The basic objective of this course is to familiarize the students with literary achievement of some of the significant Indian Writers whose works are available in English Translation. The course acquaints the students with modern movements in Indian thought to compare the treatment of different themes and styles in the genres of short story, fiction, poetry and drama as reflected in the prescribed translations. UNIT - I Premchand Nirmala UNIT - II Saadat Hasan Manto, (i) Toba Tek Singh Short Stories (ii) The Dog of Tithwal (iii) The Price of Freedom UNIT III Amrita Pritam The Revenue Stamp: An Autobiography 3 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version UNIT IV Mohan Rakesh Half way House UNIT V Gulzar (i) Amaltas (ii) Distance (iii)Have You Seen The Soul (iv)Seasons (v) The Heart Seeks Mode of Examination The Paper will be divided into section A, B and C. -

Col Col CW-2 DRAFT GAZETTE of INDIA (EXTRAORDINARY) PART I

DRAFT GAZETTE OF INDIA (EXTRAORDINARY) PART I - SECTION 4 (ARMY BRANCH) B/43432/RD21/AG/CW-2 New Delhi, the 26 January 2021 No. 03(E) dated 26 January 2021. The President is pleased to grant honorary rank of Naib Risaldar/Subedar to the under mentioned NCOs on the eve of Republic Day 2021 under Para 180 of the Regulation for the Army 1987, with effect from the dates shown against their names:- TO BE NAIB RISALDAR/SUBEDAR (ON RETIREMENT) ARMOURED CORPS 1 15470753K DFR AJAY KUMAR YADAV 01-01-2021 2 15470732N DFR AJAY THAKUR 01-12-2020 3 15465795M DFR ARUN KUMAR 01-11-2020 4 15470808H DFR ASHOK KUMAR 01-01-2021 5 15465432H DFR BHARAT SINGH 01-09-2020 6 15466303P DFR BHASKARAN N R 01-12-2020 7 15465791W DFR BHRIGUNATHRAM 01-11-2020 8 15466421H DFR CHANDRAMANI 01-01-2021 9 15467035H DFR DALJEET SINGH 01-01-2021 10 15470615H DFR DEHADRAY SUDHIR DIGAMBAR 01-11-2020 11 15465929A DFR DEV KARAN RAM 01-11-2020 12 15470540W DFR DHARMENDRA SINGH 01-09-2020 13 15465550W DFR DHARMENDRA SINGH 01-09-2020 14 15466048N DFR DINESH CHANDRA 01-11-2020 15 15467150H DFR DINESH KUMAR 01-01-2021 16 15465326K DFR DINESH KUMAR SINGH 01-09-2020 17 15466034N DFR GAJRAJ SINGH 01-11-2020 18 15466222P DFR GREESH PAL SINGH 01-11-2020 19 15470587F DFR GURWINDER SINGH 01-10-2020 20 15465551Y DFR HARI OM 01-09-2020 21 15466000A DFR HARI SHANKAR 01-11-2020 22 15465724L DFR JAGBIR SINGH 01-10-2020 23 15466891N DFR JAGDISH PRASAD 01-01-2021 24 15465483W DFR JAI PRAKASH 01-09-2020 25 15466302M DFR JAITWAR REVENDER KUAMR HEMRAJ 01-11-2020 26 15465802X DFR JASBIR SINGH 01-11-2020 -

APPENDIX 1 a Full Text of the Interview with Gauri Deshpande Who Was A

APPENDIX 1 A full text of the interview with Gauri Deshpande who was a sub-editor of the weekly for nearly two years during the seventies. R. S.: How did you get into The Weekly' ? G. D.: I was offered the job by Mr. Khushwant Singh who liked m«y published work and met me in Pune where he was giving some lectures. He first asked me to do some freelance work for him and then offered me the job when he approved of that too. R.S.: was there any definite policy for the fiction section of "The Weekly' ? What was it ? How was it different from the preceding policy ? B.D.: As far as I could judge the "policy" depended entirely on the editor's taste. The sub-editor had the right of refusal but not of acceptance. The final selection was made by the editor. He seemed to like well - written, "clever" stories; he also liked "discovering" people (e.g. me II) R.S.: 'The Weekly' was not a fictional magazine. Even then almost all the issues of the periodical had stories and poems. How did it fit into the general scheme of the magazine ? G.D.: The general endeavour of the editor was to 298 make 'The Weekly' into a brighter, more popular, more accessible paper; less 'colonial' if one can say that. The changes he made in typography, layout, covers, photographs, even payment scales, all point to this. The often controversial themes of his main photo features (e.g. communities of india) and the bright new look fiction were part of the general policy. -

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

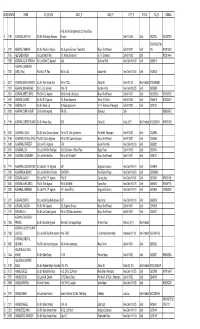

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P. -

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

628 2 - 8 November 2012 16 Pages Rs 30

#628 2 - 8 November 2012 16 pages Rs 30 HEAVY RIDE: A mahout takes his elephant on an early morning walk near the Rapti River even as Sauraha is shrouded in thick fog. BIKRAM RAI Not everybody’s cup of tea by Anurag Acharya In the arithmetic of power politics, ignoring the inclusion agenda in Procasti-Nation the Tarai may prove costly for the parties lephants have excellent they said they would use the the Nepali Congress and UML page 11 memory and they never festival season for ‘mind fresh’, which have become parties Eforget. Nepali leaders, on and come up with a consensus. singularly lacking in new the other hand, are notorious for That did not happen either. ideas, Pushpa Kamal Dahal is their forgetfulness and the ease Now they are promising a deal terrified of facing the electorate with which they backtrack on ‘by Tihar’. which is why he wants a promises. The reason there is no deal CA reincarnation by hook or Procrastination and is that no one really wants a by crook, the rump Maoists postponement have become deal. This elastic transition also want a stab at prime Best foot a way of Nepali politics, and benefits everyone: the Baburam ministership but don’t really forward the people tuned off long ago. Bhattarai-led Maoist-Madhesi care how they get there, and the The leaders had promised the coalition is perfectly happy Madhesi parties are comfortable The captain of the Nepali people who elected them that to extend its tenure so it can being sought-after kingmakers. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa KISSA-O-KALAM: THE SPEAKING PEN 2017 AN ANNUAL WORKSHOP ON WRITING AND CREATIVITY IN ENGLISH AND HINDI May 22-26, 2017, New Delhi Sahitya Akademi organized first-ever detailed event for children, the first edition of Kissa-O- Kalam: The Speaking Pen, an annual workshop for the young on creative writing in Hindi and English at the Akademi premises in New Delhi on May 22-26, 2017. This was a first of its kind initiative by the Akademi to sensitize our younger generations to our languages and literatures and to instill in them a love for the written word. This initiative, Kissa-O-Kalam: The Speaking Pen, envisaged as an annual affair with a focused interactive workshop as well as detailed individual activities held over five days encouraged and involved our children to participate and enjoy in the world of books and in the creative areas of reading and writing. Kissa-O-Kalam hopes to continue to carry forward the energy, creativity and results that were seen in this first installment in the coming years. This year, this 5-day session, held in the spacious and welcoming auditorium of the Akademi in New Delhi, from 22nd May to 26th May 2017 (Monday to Friday), was planned with a special focus to help children enjoy reading and writing both in prose and poetry, to begin to play with language, and to use language creatively and as a first step towards the creation of books. The workshop was titled Exploring Forms of Writing – Short Stories and Poetry. The workshop was opened to a final list of 50 students in the ages of 8 years to 16 years from across schools in the Delhi-NCR region. -

Aba Umar Dada Abdul Aziz Kaya

Memon Personalities Aba Umar Dada Late Mr. Dada was a well-known community leader and social worker. He was a prominent member of Karachi Cotton Exchange who earned a name for himself. After the establishment of Pakistan, he settled in the interior of Sindh and took leading part in all social and welfare activities of Hyderabad and Sindh. Settling in Karachi, he continued with his social work and was very active amongst the leaders of the Pakistan Memon Federation. Ahmed H.A. Dada He was a very prominent businessman and an active member of Karachi Stock Exchange rising to the post of its President. He was also on the Local Advisory Committee of National Bank of Pakistan, Karachi Branch, and was popular in the business circles. Abdul Aziz Kaya While in Hyderabad Deccan, he joined Ittehadul Muslimeen under the leadership of Mr. Qasim Rizvi. He worked very actively for the victims of the Indian an-ny. In Karachi, on the advice of Pakistan Ambassador Haji A. Sattar Seth, he was asked to infomi all the Hujjaj about the aims and objects of the creation of Pakistan and as such Haji Aziz started his mission. Durino Haj he rendered noteworthy services to the Hujjaj. He remained involved with his business for a couple of decades and again started his social service activities and established many institutions through which he served the people. During political turmoil when Karachi was under constant curfew for several days at a stretch, he stored consumer products and food products which he supplied at concessive rates without any profit.