An Analysis from Aristotle to Mayr's Teleological Categories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aristotle's Essentialism Revisited

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Theses Graduate Works 4-15-2013 Accommodating Species Evolution: Aristotle’s Essentialism Revisited Yin Zhang University of Missouri-St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Zhang, Yin, "Accommodating Species Evolution: Aristotle’s Essentialism Revisited" (2013). Theses. 192. http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis/192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Accommodating Species Evolution: Aristotle’s Essentialism Revisited by Yin Zhang B.A., Philosophy, Peking University, 2010 A Thesis Submitted to The Graduate School at the University of Missouri – St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Philosophy May 2013 Advisory Committee Jon D. McGinnis, Ph.D. Chairperson Andrew G. Black, Ph.D. Berit O. Brogaard, Ph.D. Zhang, Yin, UMSL, 2013, p. i PREFACE In the fall of 2008 when I was a junior at Peking University, I attended a lecture series directed by Dr. Melville Y. Stewart on science and religion. Guest lecturers Dr. Alvin Plantinga, Dr. William L. Craig and Dr. Bruce Reichenbach have influenced my thinking on the relation between evolution and faith. In the fall of 2010 when I became a one-year visiting student at Calvin College in Michigan, I took a seminar directed by Dr. Kelly J. Clark on evolution and ethics. Having thought about evolution/faith and evolution/ethics, I signed up for Dr. -

PISA Style Scientific Literacy Question on the Origin of Species

PISA Style Scientific Literacy Question On the Origin of Species – Text 1 Read the following extract from Charles Darwin’s book ‘On the Origin of Species’ ‘Can it then be thought improbable, seeing that variations useful to man have undoubtedly occurred, that other variations useful in some way to each being in the great and complex battle of life, should sometimes occur in the course of thousands of generations? If such do occur, can we doubt (remembering that many more individuals are born than can possibly survive) that individuals having an advantage, however slight, over others, would have the best chance of surviving and procreating their kind? On the other hand, we may feel that any variation in the least degree injurious would be rigidly destroyed’. Question 1 : ON THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES In this piece of text, Darwin is explaining his theory of evolution. He called this A Natural Selection B Adaptation C Inheritance D Variation Question 2 : ON THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES At the time, Darwin’s theory was not widely accepted. Which of the reasons below would explain why people did not support his idea? Reason why people did not support Darwin’s theory Yes or No ? There was little scientific evidence to support his theory Yes / No The theory of creationism as taught by the church was widely Yes / No believed and accepted People did not know about Darwin’s theory because there was no Yes / No radio or television Other scientists had come up with similar theories to Darwin Yes / No Question 3 : ON THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES Mali says that the theory of natural selection as described by Darwin in the text does not apply so well for humans. -

Father of Modern Taxonomy Carl Linnaeus

The roots of evolutionary History of Evolutionary Thought thinking Learning objectives: 2008 will mark the 150th anniversary 1. To describe major historical events and of the reading of addresses on the theory of key contributors to the development of Aristotle the theory of evolution. evolution by natural selection by Wallace and Darwin, but the roots of evolutionary thinking 384-322 BC 2. To outline the key components of Darwin’s are usually traced back to the Greek philosopher theory of evolution by natural selection. Aristotle. Aristotle developed the idea of a natural order “Scala Readings: Your text does not cover this topic (except naturae”, in which all forms of life were linked in a for box 2.1 and scattered parts of Ch. 2). “chain of being”. However, the people and events mentioned have Aristotle thought of species as unchanging and Wikipedia entries. reflecting a divine order. 336-2 1 336-2 2 Carl Linnaeus: father of Carl Linnaeus: father of modern taxonomy modern taxonomy Linnaeus is credited with developing the binomial Linnaeus recognized that individuals within a nomenclature system, in which each species name Linnaeus Linnaeus 1707-1778 species are capable of interbreeding, while 1707-1778 has two parts individuals in different species could not interbreed. Genus name + specific epithet = species name Linnaeus believed in the ‘balance of nature’, with each Cucurbita pepo = cultivated pumpkin species having a place in the divine plan. Species do Homo sapiens = modern human not change or go extinct. Later in life, Linnaeus acknowledged that new species Linnaeus also saw species as nested within broader could be formed by hybridization (by crossing groups, e.g. -

The Role of Ecological Theory in Microbial Ecology

PERSPECTIVES many areas in which microorganisms are of ESSAY environmental and economic importance. For example, improved quantitative theory The role of ecological theory could increase the efficiency of wastewater treatment processes, through the predic- tion of optimal operating conditions and in microbial ecology conditions that are likely to result in system failure. Quantitative information on the James I. Prosser, Brendan J. M. Bohannan, Tom P. Curtis, Richard J. Ellis, links between microbial community structure, Mary K. Firestone, Rob P. Freckleton, Jessica L. Green, Laura E. Green, population dynamics and activities will also Ken Killham, Jack J. Lennon, A. Mark Osborn, Martin Solan, facilitate assessment and, potentially, mitiga- Christopher J. van der Gast and J. Peter W. Young tion of microbial contributions to climate change, and should lead to quantitative Abstract | Microbial ecology is currently undergoing a revolution, with predictions of the impact of climate change repercussions spreading throughout microbiology, ecology and ecosystem science. on microbial contributions to specific eco- The rapid accumulation of molecular data is uncovering vast diversity, abundant system processes. Given the high abundance, biomass, diversity and global activities of uncultivated microbial groups and novel microbial functions. This accumulation of microorganisms, the ecological theory that data requires the application of theory to provide organization, structure, has been developed for plants and animals mechanistic insight and, -

Seeing the Smaller Picture

OPINION NATURE|Vol 453|29 May 2008 Seeing the smaller picture Advances in imaging techniques are transforming microbiology into a science that is rich in visual imagery, harking back to biology’s pre-darwinian origins, explains Martin Kemp. Most sciences go through visual and non-visual the founding fathers of modern biology (read who have commitments to particular methods phases. There are times when attempts to visu- molecular biology) were physicists who were and tools. Nevertheless, important frontiers in alize and represent nature stand at the cutting used to abstractions and numbers and didn’t biology and biophysics are being furthered by edge. At others, measurement, statistics and have the urge to look at anything. Others who picturing; data obtained at previously unsee- algebra hold sway. The two modes are cyclical. should have known better were probably cowed able scales can be translated into vivid visual Visual phases are often driven by the advent or seduced by these amazing people.” models that serve to investigate, explicate and of technologies that allow us to travel optically A new world of structural biology has been illustrate forms and mechanisms. The dimen- into new realms, minute or vast. opened up by advances in imaging techniques. sions are much smaller than those Ehrenberg Until Charles Darwin (1809–1882), biology As Schaechter says, we can now “see how an imagined, but he would have understood the in its macro form was the most visually rich enzyme works or how macromolecules interact priority accorded to visual tools for understand- of sciences. But Darwin’s visual austerity was with molecules large and small .. -

Speciation, Species Concepts, and Biogeography Illustrated by a Buckwheat Complex (Eriogonum Corymbosum)

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2009 Speciation, Species Concepts, and Biogeography Illustrated by a Buckwheat Complex (Eriogonum corymbosum) Mark W. Ellis Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Ellis, Mark W., "Speciation, Species Concepts, and Biogeography Illustrated by a Buckwheat Complex (Eriogonum corymbosum)" (2009). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 370. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/370 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i SPECIATION, SPECIES CONCEPTS, AND BIOGEOGRAPHY ILLUSTRATED BY A BUCKWHEAT COMPLEX (ERIOGONUM CORYMBOSUM) by Mark W. Ellis A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Biology Approved: ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Paul G. Wolf Dr. Karen E. Mock Major Professor Committee Member ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Michael E. Pfrender Dr. Leila Shultz Committee Member Committee Member ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Carol D. von Dohlen Dr. Byron R. Burnham Committee Member Dean of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2009 ii Copyright © Mark W. Ellis, 2009 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Speciation, Species Concepts, and Biogeography Illustrated by a Buckwheat Complex (Eriogonum corymbosum) by Mark W. Ellis, Doctor of Philosophy Utah State University, 2009 Major Professor: Dr. Paul G. Wolf Department: Biology The focus of this research project is the complex of infraspecific taxa that make up the crisp-leaf buckwheat species Eriogonum corymbosum (Polygonaceae), which is distributed widely across southwestern North America. -

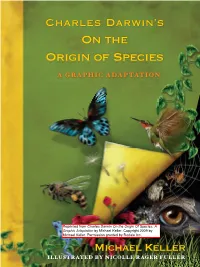

Charles Darwin's on the Origin of Species

$19.99 $25.50 CAN Science/Graphic Novel Charles Charles Darwin’s On the A stunning graphic adaptation Darwin’s Origin of Species of one of the most famous, contested, ABOUT THE AUTHORS Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, and important books of all time. Michael Keller, an award-winning the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, Few books have been as contro- journalist and writer, has a bachelor the production of the higher animals directly follows. There is A GRAPHIC ADAPTATION versial or as historically signifi cant of science degree in wildlife ecology as Charles Darwin’s On the Origin a grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been from the University of Florida and a On of Species by Means of Natural Selec- master’s degree from the Columbia originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms tion, or the Preservation of Favoured University Graduate School of Jour- or into one . and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on the COVER TK Races in the Struggle for Life. Since the nalism. according to the fi xed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning moment it was released on Novem- Origin ber 24, 1859, Darwin’s masterwork endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, Nicolle Rager Fuller is a pro- has been heralded for changing the fessional illustrator, with a bachelor and are being, evolved. course of science and condemned for of arts degree in biochemistry from —Charles Darwin, from On the Origin of Species its implied challenges to religion. -

GREAT BIOLOGISTS of the WORLD

Biology Series-1 (English) GREAT BIOLOGISTS of THE WORLD Collected & Edited by Assisted by Prof. Sunil D. Purohit Dr. Renu Tripathi Published by Society for Promotion of Science Education and Research 11-12, New Ganpati Nagar-A, Bohra Ganesh Marg, Udaipur (Rajasthan) N ISSIO D MI N AN VIS IO Promong Excellence in Science Educaon and Research Through Sciencezaon (Science S e n s i z a o n ) , S u p p o r v e Teaching, Conceptual and Pracce Learning and Training as a part of Academic Social Responsibility Program (ASRP) SPSER SPSER Published by Society for Promotion of Science Education and Research 11-12, New Ganpati Nagar-A, Bohra Ganesh Marg, Udaipur-313001 (Rajasthan) e-mail : [email protected] First Edition : 2019 Printed by : Apex Printing House Contribution Amount: Rs. 10.00 only Great Biologists of the World 40 GREAT BIOLOGISTS OF THE WORLD Collected and Edited by Professor Sunil Dutta Purohit Former Head, Department of Botany Mohanlal Sukhadia University, Udaipur (Raj.) Assisted by Dr. Renu Tripathi (Sukhwal) New Middle East International School, Riyadh Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Financial Support Dr. Renu-Sunil Dutt Tripathi Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Published by Society for Promotion of Science Education and Research 11-12, New Ganpati Nagar-A, Bohra Ganesh Marg, Udaipur (Rajasthan) Great Biologists of the World 41 CONTENTS 1. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 1 2. Robert Hooke 4 3. Carolus Linnaeus 8 4. Edward Jenner 12 5. Charles Darwin 16 6. Louis Pasteur 20 7. Gregor Mendel 24 8. Robert Koch 28 9. Alexander Fleming 32 10. Max Delbruck 35 1 Antonie van Leeuwenhoek Father of Microbiology Antonie van Leeuwenhoek is known as Father of Microbiology. -

On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin

On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin A digital edition of 1859 London Origin of Species Adam M. Goldstein, editor On the Origin of Species On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin A digital edition of the 1859 London Origin of Species Adam M. Goldstein, editor “Now let us see how this principle of great benefit being derived from divergence of character, combined with the principles of natural selection and of extinction, will tend to act. The accompanying diagram will aid us in understanding this rather perplexing subject.” Darwin Manuscripts Project David Kohn, General Editor Adam M. Goldstein, Associate Editor American Museum of Natural History New York, 2011 http://darwin.amnh.org Object Catalog Metadata The origin of species : a digital edition of the 1859 London Origin of Species / by Charles Darwin ; Adam M. Goldstein, editor. New York : American Museum of Natural History, 2011. 1 fig., xxxii + 298 pp. Computer data (1 file: 6,400,000 bytes). Represents a printed book; suitable for download, printing. Includes editor’s introduction, index. PDF v. 1.5 created by LATEX with hyperref package, encoded with pdfTEX-1.40.11. Access to the electronic resource is through the Hypertext Transfer Protocol from (HTTP) http://darwin.amnh.org. DOI TBA. Copyright c 2011 by The American Museum of Natural History. Contents Contents ix Editor’s Introduction xiii Methods & standards . xiii Typesetting this text . xx The Origin’s online readership and its discontents . xxi Concluding remarks . xxx Key to Annotations xxxi On the Origin of Species Introduction 1 1 Variation under domestication 5 Causes of Variability; Effects of Habit; Correlation of Growth; Inher- itance; Character of Domestic Varieties; Difficulty of distinguishing between Varieties and Species; Origin of Domestic Varieties from one or more Species; Domestic Pigeons, their Differences and Origin; Principle of Selection anciently followed, its Effects; Methodical and Unconscious Selection; Unknown Origin of our Domestic Productions; Circumstances favourable to Man’s power of Selection. -

18 | Evolution and the Origin of Species 467 18 | EVOLUTION and the ORIGIN of SPECIES

Chapter 18 | Evolution and the Origin of Species 467 18 | EVOLUTION AND THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES Figure 18.1 All organisms are products of evolution adapted to their environment. (a) Saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea) can soak up 750 liters of water in a single rain storm, enabling these cacti to survive the dry conditions of the Sonora desert in Mexico and the Southwestern United States. (b) The Andean semiaquatic lizard (Potamites montanicola) discovered in Peru in 2010 lives between 1,570 to 2,100 meters in elevation, and, unlike most lizards, is nocturnal and swims. Scientists still do no know how these cold-blood animals are able to move in the cold (10 to 15°C) temperatures of the Andean night. (credit a: modification of work by Gentry George, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; credit b: modification of work by Germán Chávez and Diego Vásquez, ZooKeys) Chapter Outline 18.1: Understanding Evolution 18.2: Formation of New Species 18.3: Reconnection and Rates of Speciation Introduction All species of living organisms, from bacteria to baboons to blueberries, evolved at some point from a different species. Although it may seem that living things today stay much the same, that is not the case—evolution is an ongoing process. The theory of evolution is the unifying theory of biology, meaning it is the framework within which biologists ask questions about the living world. Its power is that it provides direction for predictions about living things that are borne out in experiment after experiment. The Ukrainian-born American geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky famously wrote that [1] “nothing makes sense in biology except in the light of evolution.” He meant that the tenet that all life has evolved and diversified from a common ancestor is the foundation from which we approach all questions in biology. -

Why Was Darwin's View of Species Rejected by Twentieth Century

Biol Philos (2010) 25:497–527 DOI 10.1007/s10539-010-9213-7 Why was Darwin’s view of species rejected by twentieth century biologists? James Mallet Published online: 1 May 2010 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 Abstract Historians and philosophers of science agree that Darwin had an understanding of species which led to a workable theory of their origins. To Darwin species did not differ essentially from ‘varieties’ within species, but were distin- guishable in that they had developed gaps in formerly continuous morphological variation. Similar ideas can be defended today after updating them with modern population genetics. Why then, in the 1930s and 1940s, did Dobzhansky, Mayr and others argue that Darwin failed to understand species and speciation? Mayr and Dobzhansky argued that reproductively isolated species were more distinct and ‘real’ than Darwin had proposed. Believing species to be inherently cohesive, Mayr inferred that speciation normally required geographic isolation, an argument that he believed, incorrectly, Darwin had failed to appreciate. Also, before the sociobiology revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, biologists often argued that traits beneficial to whole populations would spread. Reproductive isolation was thus seen as an adaptive trait to prevent disintegration of species. Finally, molecular genetic markers did not exist, and so a presumed biological function of species, repro- ductive isolation, seemed to delimit cryptic species better than character-based criteria like Darwin’s. Today, abundant genetic markers are available and widely used to delimit species, for example using assignment tests: genetics has replaced a Darwinian reliance on morphology for detecting gaps between species. -

Darwin and Species

Version: 2 January 2020 Darwin and species James Mallet Galton Laboratory, Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment, University College London, 4 Stephenson Way, LONDON NW1 2HE, UK Corresponding author: James Mallet ([email protected]) tel: +44 - (0)20 7679 7412 In: Michael Ruse (ed.) 2013, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Darwin and Evolutionary Thought. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 109-115. Keywords: Species concepts, genotypic clusters, phylogenetic species concept, biological species concept, assignment tests, coalescent Mallet: Darwin & Species 1 Essay 11 Darwin and Species James Mallet ne would have thought that, by now, 150 years after the Origin , biologists could agree on a single dei nition of species. Many biologists had indeed O begun to settle on the “biological species concept” in the late modern syn- thesis (1940–70), when new i ndings in genetics became integrated into evolutionary biology. However, the consensus was short-lived. From the 1980s until the present, it seems not unfair to say that there arose more disagreement than ever before about what species are. How did we get into this situation? And what does it have to do with Darwin? Here, I argue that a series of historical misunderstandings of Darwin’s statements in the Origin contributed at least in part to the saga of conl ict among biologists about species that has yet to be resolved. Today, Darwinian ideas about species are becoming better understood. At long last, the outlines of a new and more robust Darwinian synthesis are becoming evident. This “resynthesis” (as it perhaps should be called) mixes Darwin’s original evolutionary ideas about species with evi- dence from modern molecular and population genetics.