Reply Brief of Petitioners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Capital, the State, and Chinese Workers: the Foxconn Experience

MCX38410.1177/0097700 447164412447164Pun and ChanModern China © 2012 SAGE Publications Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Articles Modern China 38(4) 383 –410 Global Capital, the State, © 2012 SAGE Publications Reprints and permission: and Chinese Workers: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0097700412447164 The Foxconn Experience http://mcx.sagepub.com Pun Ngai1 and Jenny Chan2 Abstract In 2010, a startling 18 young migrant workers attempted suicide at Foxconn Technology Group production facilities in China. This article looks into the development of the Foxconn Corporation to understand the advent of capi- tal expansion and its impact on frontline workers’ lives in China. It also pro- vides an account of how the state facilitates Foxconn’s production expansion as a form of monopoly capital. Foxconn stands out as a new phenomenon of capital expansion because of the incomparable speed and scale of its capital accumulation in all regions of China. This article explores how the workers at Foxconn, the world’s largest electronics manufacturer, have been subjected to work pressure and desperation that might lead to suicides on the one hand but also open up daily and collective resistance on the other hand. Keywords global capital, Chinese state, student workers, rural migrant workers, Foxconn Technology Group When Time magazine nominated workers in China as the runners-up for the 2009 Person of the Year, the editor commented that Chinese workers have brightened the future of humanity by “leading the world to economic 1Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong 2Royal Holloway, University of London, Surrey, UK Corresponding Author: Pun Ngai, Department of Applied Social Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong Email: [email protected] 384 Modern China 38(4) recovery” (Time, Dec. -

“UROP Has Long Represented the Opportunity to Discover, Innovate and Create New Knowledge. the EECS Superurop Promises MIT Un

“UROP has long represented the opportunity to discover, innovate and create new knowledge. The EECS SuperUROP promises MIT undergraduates an even more intensive and sustained intellectual SuperUROP experience working with our faculty. We expect EECS majors will welcome this new opportunity with enthusiasm.” — Julie B. Norman Senior Associate Dean for Undergraduate Education Director, Office of Undergraduate Advising and Academic Programming 2012– 2013 I am thrilled to celebrate the launch of the new Advanced Undergraduate Research Program in EECS, now officially known as SuperUROP. This collaboration between EECS and the MIT UROP office evolved out of the 2012 EECS strategic plan, which included strong participation from faculty, students, and staff. The program responded to my vision for creating a high caliber undergraduate research program that would produce publication- worthy results. The Undergraduate Student Advisory Group in EECS (USAGE) strongly influenced the overall structure of the program. The SuperUROP program will provide a jump-start on graduate school, act as a startup accelerator, and be an industry-training bootcamp—all rolled “Our engineering students want a into one. The response from students has been extremely positive. We have 86 students participating this inaugural year, and expect that number will deeper understanding of the topics increase in the future. they care about, and they want to apply SuperUROP students engage in a year-long research experience and participate in a course titled “Preparation for Undergraduate Research,” which covers a range of subjects, from selecting projects and research this knowledge in a way that will lead topics in EECS to entrepreneurship and ethics in engineering. -

Independent Accountants' Review Report

(English Translation of Financial Report Originally Issued In Chinese) QUANTA COMPUTER INC. FINANCIAL STATEMENTS JUNE 30, 2012 AND 2011 (WITH INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT THEREON) Address: No. 188 Wen Hwa 2nd Rd., Kuei Shan Hsiang , Tao Yuan Shien, Taiwan Telephone: 886-3-327-2345 - 1 - WorldReginfo - ff7f59af-5a34-4c96-b8cd-29c8690ed675 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Page Cover Page 1 Table of Contents 2 Independent Auditor’s Report 3 Balance Sheets 4 Statements of Income 5 Statements of Changes in Stockholders’ Equity 6 Statements of Cash Flows 7 Notes to Financial Statements 8-48 - 2 - WorldReginfo - ff7f59af-5a34-4c96-b8cd-29c8690ed675 (English Translation of Financial Report Originally Issued In Chinese) Independent Auditors’ Report To the Board of Directors and Shareholders of Quanta Computer Inc.: We have audited the accompanying balance sheets of Quanta Computer Inc. (the Company) as of June 30, 2012 and 2011, and the related statements of income, changes in stockholders’ equity, and cash flows for the six months then ended. These financial statements are the responsibility of the Company’s management. Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these financial statements based on our audits. Except as described in the following paragraph, we conducted our audits in accordance with “Rules Governing Auditing and Certification of Financial Statements by Certified Public Accountants” and auditing standards generally accepted in the Republic of China. Those regulations and standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement. An audit includes examining, on a test basis, evidence supporting the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements. -

Shape of Automation

Ling-Fei Lin The [Shapeless] Shape of Automation: Moments of Constructing Factory Robots in East Asia Ling-Fei Lin, Harvard University For WeRobot 2018 Conference @ Stanford Law School Creation brings transformation and also destruction, but in what shape? When robots and automation gradually penetrate into factory life in East Asia, what will the micro production landscape look like? At the transitioning moment of constructing and using assembly robots, changes are never linear and straightforward. When new robotic species are made, one by one, by their human creators, long-term human practices are segmented, analyzed, rationalized, and then mechanized. It is not the whole body, but anatomized parts and functions that are replaced. Furthermore, they bring equally shocking effects to those who work with the replaced core. With new functions and potentially new divisions of labor, robots start to compete and co-evolve with (parts of) humans and their practices, although usually with overwhelming power over their competitors. Laptop Production Landscape East Asia has been a major production base for global consumer electronics and computer products for a few decades, in particular after the 1980s. In the laptop industry, annually around 50-90% of worldwide products were made by Taiwanese contract manufacturers with their factories in China after 2001, including Quanta Computer, Compal Electronics, Wistron Corpration and Foxconn Technology, producing brand products for Apple, Dell, Hewlett Packard, Acer, Asus and so on. The emerging usage of assembly robots in computer factories is a watershed and provides us with an excellent opportunity to explore the inner social world of producers since 1 Ling-Fei Lin all elements have to react to this changing moment. -

Zettacom Raises $47.5 Million in Second Round -- Second Round Funding Led by Granite Global Ventures

Contact: Amy Caplan ZettaCom, Inc, (408) 869-7000 [email protected] ZettaCom Raises $47.5 Million in Second Round -- Second Round Funding Led by Granite Global Ventures -- Santa Clara, Calif. – June 19, 2001 – ZettaCom, Inc., a leading supplier of high-performance and configurable optical silicon solutions, announced today that it has successfully completed the closing of its Series B equity round with a total amount of $47.5 million. This substantial round helps position ZettaCom as a significant force in the semiconductor components arena, and brings the total amount of equity financing issued, raised and committed to $58.5 million since the company’s inception in 1999. According to RHK, a leading telecommunications market research firm, the optical silicon market currently represents 15% of total service infrastructure spending. Optical silicon devices will result in a market that will grow to over $12 billion in 2005. ZettaCom’s unique background and product strategy will position it as a leader in this huge emerging market. Over twelve major design wins in the last seven months validate ZettaCom’s claim to leadership in this space. The company’s recent infusion of funds will accelerate the build-out of ZettaCom’s specialized communication ICs (integrated circuits), expansion of its national operations, further development initiatives, and continued growth of the company’s highly skilled, professional teams. The Series B investors include: Granite Global Ventures, Venrock Associates, Norwest Venture Partners, J. & W. Seligman & Co., Development Bank of Singapore, JPMorgan Partners (NYSE:JPM), k1 Ventures, Vertex Management, Crimson Ventures, Infineon Ventures, U.S. Bancorp Piper Jaffray (NYSE:USB), SG Cowen Ventures Fund, Banc of America Securities LLC (NYSE:BAC), and United Investments. -

Taiwanese PC Makers Hang Big Hopes on Small Laptops

E-Commerce Times > Enterprise IT > Hardware Taiwanese PC Makers Hang Big Hopes on Small Laptops By Annie Huang AP 02/23/09 9:08 AM PT Taiwanese computer makers may find it easier to the weather worldwide economic troubles thanks to tiny notebooks, also known as netbooks. Two major manufacturers there -- Acer and Asus -- lead the market in low-cost, small-sized netbooks, which many consumers see as a wise purchase given tightening household budgets. Thinking small might help Taiwan's computer industry emerge from the global downturn as an even bigger global player. While the worldwide computer market is suffering through its worst sales in years, one bright spot is coming from the mini-laptops known as "netbooks," which appeal to the budget-conscious in tough times. Several research groups have forecast that global demand for the thin, light machines could double this year -- and the category is dominated by Taiwanese brands and Taiwanese contract manufacturers. With the island's $2.5 billion in electronics exports accounting for one-fifth of Taiwan's overall exports in January, Taiwanese government planners hope netbooks can boost an economy that is struggling. At 5 percent, unemployment is moderate by worldwide standards but at a five-year high in Taiwan. With exports registering two consecutive monthly drops of more than 40 percent year-over-year, economists are predicting a 3 to 6 percent contraction in the Taiwanese economy for 2009. Convenient Sizes Taiwan-made mini-laptops burst onto the world's electronics scene with an estimated 11 million units sold last year. This year, sales could hit 22 million units, according to several analysts. -

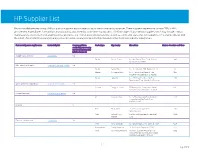

HP Supplier List

HP Supplier List Below is an alphabetized listing of HP production suppliers and information about their sustainability practices. These suppliers represent more than 95% of HP’s procurement expenditures for materials, manufacturing, and assembly at the time of publication. This list includes final assembly suppliers, which may include contract manufacturers, electronic manufacturing service providers, and original design manufacturers, as well as commodity and component suppliers. HP is sharing this list with the intent of promoting transparency and progress in raising social and environmental standards in the electronics industry supply chain. Final assembly parent supplier name Sustainability link Company publishes Product type City, Country Site address Number of workers on HP lines sustainability report using the Global Reporting (GRI) Initiative framework AU Optronics Corporation Sustainability Yes Display Suzhou, China No. 398, Suhong Zhong Road, Suzhou 890 Industrial Park, 215021 BOE Technology Group Co. Corporate Social Responsibility Yes Display Beijing, China No.118 Jinghaiyilu, BDA, Beijing, 100176 50 Display Chongqing, China No. 7, Yunhan Road, Shuitu Hi Tech 950 Industrial Park, Beibei District, 400700 Display Hefei, China No.2177, Great East Road, Xin Zhan 150 Development Zone, Hefei, An Hui Province Cheng Uei Precision Industry Co. Corporate Responsibility Yes Scanner Dongguan, China FIT Industry Park, Yinhe Industrial Area, 1013 Qingxi, Dongguan Guangdong Province Compal Electronics Sustainable Development Yes PC Kunshan, -

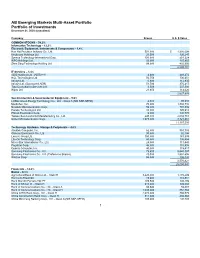

Printmgr File

AB Emerging Markets Multi-Asset Portfolio Portfolio of Investments December 31, 2020 (unaudited) Company Shares U.S. $ Value COMMON STOCKS – 54.3% Information Technology – 13.3% Electronic Equipment, Instruments & Components – 1.4% Hon Hai Precision Industry Co., Ltd. 551,000 $ 1,806,699 Kingboard Holdings Ltd. 28,500 120,247 Synnex Technology International Corp. 150,000 251,324 WPG Holdings Ltd. 68,000 103,965 Zhen Ding Technology Holding Ltd. 99,000 402,866 2,685,101 IT Services – 1.4% GDS Holdings Ltd. (ADR)(a) (b) 4,800 449,472 HCL Technologies Ltd. 56,758 736,851 Infosys Ltd. 6,600 112,935 Infosys Ltd. (Sponsored ADR) 51,706 876,417 Tata Consultancy Services Ltd. 8,589 337,508 Wipro Ltd. 21,653 114,620 2,627,803 Semiconductors & Semiconductor Equipment – 5.9% LONGi Green Energy Technology Co., Ltd. - Class A (Nth SSE-SEHK) 4,600 65,316 MediaTek, Inc. 70,000 1,866,710 Novatek Microelectronics Corp. 59,000 776,339 Parade Technologies Ltd. 10,000 395,913 Phison Electronics Corp. 9,000 106,776 Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Ltd. 245,000 4,634,781 United Microelectronics Corp. 1,975,000 3,321,481 11,167,316 Technology Hardware, Storage & Peripherals – 4.6% Asustek Computer, Inc. 62,000 553,703 Chicony Electronics Co., Ltd. 30,000 92,196 Lenovo Group Ltd. 150,000 141,809 Lite-On Technology Corp. 60,000 106,454 Micro-Star International Co., Ltd. 24,000 113,443 Pegatron Corp. 46,000 110,436 Quanta Computer, Inc. 40,000 115,417 Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. -

ACER INCORPORATED and SUBSIDIARIES Consolidated Financial Statements December 31, 2011 and 2010 (With Independent Auditors’ Report Thereon)

ACER INCORPORATED AND SUBSIDIARIES Consolidated Financial Statements December 31, 2011 and 2010 (With Independent Auditors’ Report Thereon) Independent Auditors’ Report The Board of Directors Acer Incorporated: We have audited the accompanying consolidated balance sheets of Acer Incorporated (the “Company”) and subsidiaries as of December 31, 2011 and 2010, and the related consolidated statements of operations, changes in stockholders‟ equity, and cash flows for the years then ended. These consolidated financial statements are the responsibility of the Company‟s management. Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these financial statements based on our audits. We conducted our audits in accordance with the “Regulations Governing Auditing and Certification of Financial Statements by Certified Public Accountants” and auditing standards generally accepted in the Republic of China. Those regulations and standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement. An audit includes examining, on a test basis, evidence supporting the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements. An audit also includes assessing the accounting principles used and significant estimates made by management, as well as evaluating the overall financial statement presentation. We believe that our audits provide a reasonable basis for our opinion. In our opinion, the consolidated financial statements referred to in the first paragraph present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of Acer Incorporated and subsidiaries as of December 31, 2011 and 2010, and the results of their consolidated operations and their consolidated cash flows for the years then ended, in conformity with the accounting principles generally accepted in the Republic of China. -

Apple Watch Series 4 – Still Failed to Protect Teenage

Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour Telephone: (852) 2392 5464 Fax: (852) 2392 5463 Email: [email protected] Website: www.sacom.hk Mailing Address: P.O.Box No. 79583, Mongkok Post Office, HONG KONG Apple Watch Series 4 Still Failed to Protect Teenage Student Workers A Re-visiting Investigative Report on Apple Watch’s Exclusive Manufacturer (Figure 1: Quanta Chongqing’s workers finishing work) 1 Index Executive Summary Page 3 SACOM’s Demands to Apple Page 4 1. Background of the Research Page 5 1.1 Basic Information on Quanta Computer Page 6 - 7 1.2 Apple’s Student Workers Violations in Recent Years Page 8 - 9 1.3 Chinese Regulations and Apple’s CSR Policy Regarding Student Workers Page 10 1.4 Methodology Page 11 2. Research Findings 2.1 “Internship” Program without Educational Elements 2.1.1 Majors Unrelated to the Electronics Industry Page 12 2.1.2 Absence of Educational Objectives and Assignments Page 13 - 14 2.2 Forced Labour? – Punishment for Refusing to Work Page 15 - 16 2.3 Illegal Overtime Work and Night-Shift Arrangements Page 17 - 18 2.4 Unlawful Recruitment of First Year Students Page 19 3. Conclusion and Demands 3.1 Conclusion Page 20 3.2 SACOM’s Demands to Apple Page 21 4. Acknowledgements Page 22 2 Executive Summary In 2017, Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour (SACOM) published the investigative report “Apple Watch 3 – Exploit Student Workers Further. An Investigative Report on Apple Watch’s Exclusive Manufacturer” disclosing Apple’s plan to relocate the Apple Watch production to Quanta Computer’s Chongqing factory and the student workers violations found in it. -

Quanta Computer Inc. Annual Report 2015

Quanta Computer Inc. Annual Report 2015 WorldReginfo - 4c253b32-c813-49eb-99f6-4937438e8299 Report to Shareholders Year 2015 was a challenging year as the global economy remains lackluster and the consumer market slowly recovers. Despite the challenging macro environment, Quanta Computer remains positive and continues to identify innovative ways to overcome obstacles ahead. The Company leverages innovative thinking to optimize current operations. We also adopt the thinking of “Core Motive is Innovation” and “Action Plan Is Change” in the process of new product development. Employees and management team at Quanta Computer work together as a team with relentless efforts. The Company’s revenue returned to a trillion dollar in FY2015 as a result of team efforts and strong determination from every employee in the Company. Quanta’s performance for FY2015 and outlook for FY2016 are as follow: I. Revenue and Income Consolidated revenue in year 2015 was NT$1,007.3BN, an increase of 8.7% from the previous year. Net income after tax in FY2015 and FY2014 was NT$17.8BN and NT$19.2BN respectively. Net income attributable to owners of parent in FY2015 and FY2014 was NT$17.8BN and NT$18.9BN respectively. EPS in FY2015 was NT$4.62. Non-operating income was NT$4.4BN. Growth for the PC industry remains lukewarm in 2015 due to instability of the global economy and geopolitical volatility. Moreover, fluctuation of foreign currency further deepened the difficulty of overall business operation. To concur the ever-changing challenges ahead, Quanta Computer repositioned its strategy and followed through four action plans defined in 2014, which are identifying opportunities ahead of competitions; acceleration; simplicity and cost savings. -

(SOW) Environmentally Conscious Electronics TIG Inemi HFR-Free Technology Leadership Program

iNEMI Statement of Work (SOW) Environmentally Conscious Electronics TIG iNEMI HFR-Free Technology Leadership Program Version 5.0 Date: May 15, 2009 Program Manager: Stephen Tisdale, Intel Corporation PCB Materials Project Chair: John Davignon, Intel Corporation PCB Materials Project Co-chair: TBD Signal Integrity Project Chair: Stephen Hall, Intel Corporation Signal Integrity Project Co-chair: David Senk, Cisco Systems iNEMI Coach: Jim Arnold Table of Contents Purpose…………………………………………………………. 2 Background and Motivation……………………………………. 2 Goals of the Project…………………………………………….. 2 Is / Is Not……………………………………………………….. 3 Scope of Work………………………………………………….. 3 Anticipated Outcome…………………………………………… 5 Participant Profile………………………………………………. 5 Resources Required from Participants………………………….. 5 Program Formation Participants………………………………... 6 Project Participant Commitment Matrix………………………... 11 Task Schedule...………….……………………………………… 13 PCB Materials & Signal Integrity Project Monitoring Plans……. 15 Outcome of the Program….……………………………..………. 15 General and Administrative Guidelines….….…………………… 16 Page 1 of 16 Purpose: Identify key electrical and mechanical HFR-free PCB material characteristics to material suppliers and identify a proposed set of technology guidelines. Identify supply chain readiness, supply capability and material parameter characteristics for “HFR-free” alternatives to conventional printed wiring board materials and printed wiring board assemblies. Background and Motivation: The European Union’s Restriction on the use of certain Hazardous