Design Engineering Or Factory Capability? Building Laptop Contract Manufacturing in Taiwan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reply Brief of Petitioners

No. 06-937 In the Supreme Court of the United States QUANTA COMPUTER, INC., QUANTA COMPUTER USA, INC., Q-LITY COMPUTER, INC., COMPAL ELECTRONICS, INC., BIZCOM ELECTRONICS, INC., SCEPTRE TECHNOLOGIES, INC., FIRST INTERNATIONAL COMPUTER, INC. AND FIRST INTERNATIONAL COMPUTER OF AMERICA, INC., PETITIONERS, V. LG ELECTRONICS, INC., RESPONDENT. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT REPLY BRIEF OF PETITIONERS TERRENCE D. GARNETT MAUREEN E. MAHONEY VINCENT K. YIP Counsel of Record PETER WIED J. SCOTT BALLENGER PAUL, HASTINGS, JANOFSKY ANNE W. ROBINSON & WALKER LLP LATHAM & WATKINS LLP 515 SOUTH FLOWER STREET 555 11TH STREET N.W. 25TH FLOOR SUITE 1000 LOS ANGELES, CA 90071 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20004 (213) 683-6000 (202) 637-2200 Counsel for Quanta Computer, Counsel for Petitioners Inc., Quanta Computer USA, Inc., Q-Lity Computer, Inc. Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Cover MAXWELL A. FOX WILLIAM J. ANTHONY, JR. PAUL, HASTINGS, JANOFSKY ERIC L. WESENBERG & WALKER LLP KAI TSENG 34 F ARK MORI BUILDING MATTHEW J. HULT P.O. BOX 577 ROWENA Y. YOUNG 12-32 AKASAKA 1-CHOME ORRICK, HERRINGTON MINATO-KU, TOKYO 107-6034 & SUTCLIFFE LLP JAPAN 1000 MARSH ROAD 813 6229 6100 MENLO PARK, CA 94025 Counsel for Quanta (650) 614-7400 Computer, Inc., Quanta Counsel for Compal Electronics, Computer USA, Inc., Q-Lity Inc., Bizcom Electronics, Inc., Computer, Inc. Sceptre Technologies, Inc. RONALD S. LEMIEUX PAUL, HASTINGS, JANOFSKY & WALKER LLP 5 PALO ALTO SQUARE 6TH FLOOR PALO ALTO, CA 94306 Counsel for First International Computer, Inc. and First International Computer of America, Inc. -

Global Capital, the State, and Chinese Workers: the Foxconn Experience

MCX38410.1177/0097700 447164412447164Pun and ChanModern China © 2012 SAGE Publications Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Articles Modern China 38(4) 383 –410 Global Capital, the State, © 2012 SAGE Publications Reprints and permission: and Chinese Workers: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0097700412447164 The Foxconn Experience http://mcx.sagepub.com Pun Ngai1 and Jenny Chan2 Abstract In 2010, a startling 18 young migrant workers attempted suicide at Foxconn Technology Group production facilities in China. This article looks into the development of the Foxconn Corporation to understand the advent of capi- tal expansion and its impact on frontline workers’ lives in China. It also pro- vides an account of how the state facilitates Foxconn’s production expansion as a form of monopoly capital. Foxconn stands out as a new phenomenon of capital expansion because of the incomparable speed and scale of its capital accumulation in all regions of China. This article explores how the workers at Foxconn, the world’s largest electronics manufacturer, have been subjected to work pressure and desperation that might lead to suicides on the one hand but also open up daily and collective resistance on the other hand. Keywords global capital, Chinese state, student workers, rural migrant workers, Foxconn Technology Group When Time magazine nominated workers in China as the runners-up for the 2009 Person of the Year, the editor commented that Chinese workers have brightened the future of humanity by “leading the world to economic 1Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong 2Royal Holloway, University of London, Surrey, UK Corresponding Author: Pun Ngai, Department of Applied Social Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong Email: [email protected] 384 Modern China 38(4) recovery” (Time, Dec. -

Coming Back Home After the Sun Rises: Returnee Entrepreneurs and Growth of High Tech Industries

G Model RESPOL-2772; No. of Pages 17 ARTICLE IN PRESS Research Policy xxx (2012) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Research Policy jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/respol Coming back home after the sun rises: Returnee entrepreneurs and growth of high tech industries a,b c,∗ d Martin Kenney , Dan Breznitz , Michael Murphree a Department of Human and Community Development, University of California, Davis, United States b Berkeley Roundtable on the International Economy, United States c The Scheller College of Business, Georgia Institute of Technology, United States d Sam Nunn School of International Affairs, Georgia Institute of Technology, United States a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Recently, the role of returnees in the economic development of various East Asian nations has received Received 6 November 2011 much attention. The early literature on the relocation of the most highly trained individuals from a devel- Received in revised form 30 July 2012 oping nation to a developed nation viewed the phenomena as a “brain drain.” Since the 1990s, a new Accepted 4 August 2012 strand of thinking has suggested that for developing nations this was actually a positive phenomenon; as Available online xxx these expatriates studied and then worked abroad, they absorbed technical expertise, managerial, and entrepreneurial skills. These theories stipulated that these expatriates then returned home, and ignited Keywords: a virtuous circle of technological entrepreneurship leading to rapid economic development. Much of this High skilled immigrants Innovation literature gives returnees a critical role in the home country’s take-off period of the local information and communications technology (ICT) industry. -

“UROP Has Long Represented the Opportunity to Discover, Innovate and Create New Knowledge. the EECS Superurop Promises MIT Un

“UROP has long represented the opportunity to discover, innovate and create new knowledge. The EECS SuperUROP promises MIT undergraduates an even more intensive and sustained intellectual SuperUROP experience working with our faculty. We expect EECS majors will welcome this new opportunity with enthusiasm.” — Julie B. Norman Senior Associate Dean for Undergraduate Education Director, Office of Undergraduate Advising and Academic Programming 2012– 2013 I am thrilled to celebrate the launch of the new Advanced Undergraduate Research Program in EECS, now officially known as SuperUROP. This collaboration between EECS and the MIT UROP office evolved out of the 2012 EECS strategic plan, which included strong participation from faculty, students, and staff. The program responded to my vision for creating a high caliber undergraduate research program that would produce publication- worthy results. The Undergraduate Student Advisory Group in EECS (USAGE) strongly influenced the overall structure of the program. The SuperUROP program will provide a jump-start on graduate school, act as a startup accelerator, and be an industry-training bootcamp—all rolled “Our engineering students want a into one. The response from students has been extremely positive. We have 86 students participating this inaugural year, and expect that number will deeper understanding of the topics increase in the future. they care about, and they want to apply SuperUROP students engage in a year-long research experience and participate in a course titled “Preparation for Undergraduate Research,” which covers a range of subjects, from selecting projects and research this knowledge in a way that will lead topics in EECS to entrepreneurship and ethics in engineering. -

Independent Accountants' Review Report

(English Translation of Financial Report Originally Issued In Chinese) QUANTA COMPUTER INC. FINANCIAL STATEMENTS JUNE 30, 2012 AND 2011 (WITH INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT THEREON) Address: No. 188 Wen Hwa 2nd Rd., Kuei Shan Hsiang , Tao Yuan Shien, Taiwan Telephone: 886-3-327-2345 - 1 - WorldReginfo - ff7f59af-5a34-4c96-b8cd-29c8690ed675 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Page Cover Page 1 Table of Contents 2 Independent Auditor’s Report 3 Balance Sheets 4 Statements of Income 5 Statements of Changes in Stockholders’ Equity 6 Statements of Cash Flows 7 Notes to Financial Statements 8-48 - 2 - WorldReginfo - ff7f59af-5a34-4c96-b8cd-29c8690ed675 (English Translation of Financial Report Originally Issued In Chinese) Independent Auditors’ Report To the Board of Directors and Shareholders of Quanta Computer Inc.: We have audited the accompanying balance sheets of Quanta Computer Inc. (the Company) as of June 30, 2012 and 2011, and the related statements of income, changes in stockholders’ equity, and cash flows for the six months then ended. These financial statements are the responsibility of the Company’s management. Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these financial statements based on our audits. Except as described in the following paragraph, we conducted our audits in accordance with “Rules Governing Auditing and Certification of Financial Statements by Certified Public Accountants” and auditing standards generally accepted in the Republic of China. Those regulations and standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement. An audit includes examining, on a test basis, evidence supporting the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements. -

Shape of Automation

Ling-Fei Lin The [Shapeless] Shape of Automation: Moments of Constructing Factory Robots in East Asia Ling-Fei Lin, Harvard University For WeRobot 2018 Conference @ Stanford Law School Creation brings transformation and also destruction, but in what shape? When robots and automation gradually penetrate into factory life in East Asia, what will the micro production landscape look like? At the transitioning moment of constructing and using assembly robots, changes are never linear and straightforward. When new robotic species are made, one by one, by their human creators, long-term human practices are segmented, analyzed, rationalized, and then mechanized. It is not the whole body, but anatomized parts and functions that are replaced. Furthermore, they bring equally shocking effects to those who work with the replaced core. With new functions and potentially new divisions of labor, robots start to compete and co-evolve with (parts of) humans and their practices, although usually with overwhelming power over their competitors. Laptop Production Landscape East Asia has been a major production base for global consumer electronics and computer products for a few decades, in particular after the 1980s. In the laptop industry, annually around 50-90% of worldwide products were made by Taiwanese contract manufacturers with their factories in China after 2001, including Quanta Computer, Compal Electronics, Wistron Corpration and Foxconn Technology, producing brand products for Apple, Dell, Hewlett Packard, Acer, Asus and so on. The emerging usage of assembly robots in computer factories is a watershed and provides us with an excellent opportunity to explore the inner social world of producers since 1 Ling-Fei Lin all elements have to react to this changing moment. -

Zettacom Raises $47.5 Million in Second Round -- Second Round Funding Led by Granite Global Ventures

Contact: Amy Caplan ZettaCom, Inc, (408) 869-7000 [email protected] ZettaCom Raises $47.5 Million in Second Round -- Second Round Funding Led by Granite Global Ventures -- Santa Clara, Calif. – June 19, 2001 – ZettaCom, Inc., a leading supplier of high-performance and configurable optical silicon solutions, announced today that it has successfully completed the closing of its Series B equity round with a total amount of $47.5 million. This substantial round helps position ZettaCom as a significant force in the semiconductor components arena, and brings the total amount of equity financing issued, raised and committed to $58.5 million since the company’s inception in 1999. According to RHK, a leading telecommunications market research firm, the optical silicon market currently represents 15% of total service infrastructure spending. Optical silicon devices will result in a market that will grow to over $12 billion in 2005. ZettaCom’s unique background and product strategy will position it as a leader in this huge emerging market. Over twelve major design wins in the last seven months validate ZettaCom’s claim to leadership in this space. The company’s recent infusion of funds will accelerate the build-out of ZettaCom’s specialized communication ICs (integrated circuits), expansion of its national operations, further development initiatives, and continued growth of the company’s highly skilled, professional teams. The Series B investors include: Granite Global Ventures, Venrock Associates, Norwest Venture Partners, J. & W. Seligman & Co., Development Bank of Singapore, JPMorgan Partners (NYSE:JPM), k1 Ventures, Vertex Management, Crimson Ventures, Infineon Ventures, U.S. Bancorp Piper Jaffray (NYSE:USB), SG Cowen Ventures Fund, Banc of America Securities LLC (NYSE:BAC), and United Investments. -

Taiwanese PC Makers Hang Big Hopes on Small Laptops

E-Commerce Times > Enterprise IT > Hardware Taiwanese PC Makers Hang Big Hopes on Small Laptops By Annie Huang AP 02/23/09 9:08 AM PT Taiwanese computer makers may find it easier to the weather worldwide economic troubles thanks to tiny notebooks, also known as netbooks. Two major manufacturers there -- Acer and Asus -- lead the market in low-cost, small-sized netbooks, which many consumers see as a wise purchase given tightening household budgets. Thinking small might help Taiwan's computer industry emerge from the global downturn as an even bigger global player. While the worldwide computer market is suffering through its worst sales in years, one bright spot is coming from the mini-laptops known as "netbooks," which appeal to the budget-conscious in tough times. Several research groups have forecast that global demand for the thin, light machines could double this year -- and the category is dominated by Taiwanese brands and Taiwanese contract manufacturers. With the island's $2.5 billion in electronics exports accounting for one-fifth of Taiwan's overall exports in January, Taiwanese government planners hope netbooks can boost an economy that is struggling. At 5 percent, unemployment is moderate by worldwide standards but at a five-year high in Taiwan. With exports registering two consecutive monthly drops of more than 40 percent year-over-year, economists are predicting a 3 to 6 percent contraction in the Taiwanese economy for 2009. Convenient Sizes Taiwan-made mini-laptops burst onto the world's electronics scene with an estimated 11 million units sold last year. This year, sales could hit 22 million units, according to several analysts. -

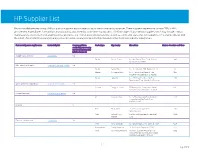

HP Supplier List

HP Supplier List Below is an alphabetized listing of HP production suppliers and information about their sustainability practices. These suppliers represent more than 95% of HP’s procurement expenditures for materials, manufacturing, and assembly at the time of publication. This list includes final assembly suppliers, which may include contract manufacturers, electronic manufacturing service providers, and original design manufacturers, as well as commodity and component suppliers. HP is sharing this list with the intent of promoting transparency and progress in raising social and environmental standards in the electronics industry supply chain. Final assembly parent supplier name Sustainability link Company publishes Product type City, Country Site address Number of workers on HP lines sustainability report using the Global Reporting (GRI) Initiative framework AU Optronics Corporation Sustainability Yes Display Suzhou, China No. 398, Suhong Zhong Road, Suzhou 890 Industrial Park, 215021 BOE Technology Group Co. Corporate Social Responsibility Yes Display Beijing, China No.118 Jinghaiyilu, BDA, Beijing, 100176 50 Display Chongqing, China No. 7, Yunhan Road, Shuitu Hi Tech 950 Industrial Park, Beibei District, 400700 Display Hefei, China No.2177, Great East Road, Xin Zhan 150 Development Zone, Hefei, An Hui Province Cheng Uei Precision Industry Co. Corporate Responsibility Yes Scanner Dongguan, China FIT Industry Park, Yinhe Industrial Area, 1013 Qingxi, Dongguan Guangdong Province Compal Electronics Sustainable Development Yes PC Kunshan, -

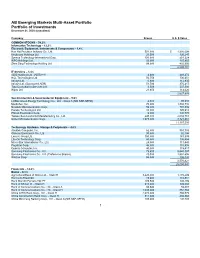

Printmgr File

AB Emerging Markets Multi-Asset Portfolio Portfolio of Investments December 31, 2020 (unaudited) Company Shares U.S. $ Value COMMON STOCKS – 54.3% Information Technology – 13.3% Electronic Equipment, Instruments & Components – 1.4% Hon Hai Precision Industry Co., Ltd. 551,000 $ 1,806,699 Kingboard Holdings Ltd. 28,500 120,247 Synnex Technology International Corp. 150,000 251,324 WPG Holdings Ltd. 68,000 103,965 Zhen Ding Technology Holding Ltd. 99,000 402,866 2,685,101 IT Services – 1.4% GDS Holdings Ltd. (ADR)(a) (b) 4,800 449,472 HCL Technologies Ltd. 56,758 736,851 Infosys Ltd. 6,600 112,935 Infosys Ltd. (Sponsored ADR) 51,706 876,417 Tata Consultancy Services Ltd. 8,589 337,508 Wipro Ltd. 21,653 114,620 2,627,803 Semiconductors & Semiconductor Equipment – 5.9% LONGi Green Energy Technology Co., Ltd. - Class A (Nth SSE-SEHK) 4,600 65,316 MediaTek, Inc. 70,000 1,866,710 Novatek Microelectronics Corp. 59,000 776,339 Parade Technologies Ltd. 10,000 395,913 Phison Electronics Corp. 9,000 106,776 Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Ltd. 245,000 4,634,781 United Microelectronics Corp. 1,975,000 3,321,481 11,167,316 Technology Hardware, Storage & Peripherals – 4.6% Asustek Computer, Inc. 62,000 553,703 Chicony Electronics Co., Ltd. 30,000 92,196 Lenovo Group Ltd. 150,000 141,809 Lite-On Technology Corp. 60,000 106,454 Micro-Star International Co., Ltd. 24,000 113,443 Pegatron Corp. 46,000 110,436 Quanta Computer, Inc. 40,000 115,417 Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. -

The ATLAS - 2014 Transdisciplinary-Transnational-Transcultural 3International T Conference ASIA University Taichung, Taiwan June 8-13, 2014 HONORING

The ATLAS - 2014 Transdisciplinary-Transnational-Transcultural 3International T Conference ASIA UNIVERSITY TaiCHUNG, TAIWAN June 8-13, 2014 HONORING Dr. BASARAB NICOLESCU 2014 TheATLAS T3 International Conference will be held at skills, educating them broadly and preparing them for an Asia University (AU). Asia University is a newly eshtablished increasingly transdisciplinary, collaborative, and global and well regarded private university located in Taichung job market. County, Taiwan. It is recognized in Taiwan for its renowned • Transdisciplinary education and preparation for the length research and teaching excellence in Health Care, computer of our life. science, and management. Asia University was founded at • new methodology in engineering education that is the beginning of the 21st century. Due to its carefully-planned focused on teaching students transdisciplinary skills development, incessant progress, and innovative break- thereby allowing them to become creative and innovative throughs, the young university has become well-recognized engineers. in numerous aspects in Taiwan and the other parts of the • Chalenges to shift from disciplinary thinking to world. transdisciplinary thinking. FOCUS OF ANNUAL MEETING SPONSORED BY • Asia University, Taichung, Taiwan 3 The T International Conference program will consist of • The Academy of Transdisciplinary Learning & Advanced 3 invited and selected papers emphasizing transdisciplinary, Studies (TheATLAS) transnational and transcultural global problems. Plenary sessions and keynote panels -

Global CEO Appointments: About the High Pay Centre Contents a Very Domestic Issue

THE NEW CLOSED SHOP: GLOBALWHO’S DECIDING CEO APPOINTMENTS:ON PAY? THE MAKE UP OF REMUNERATION COMMITTEES A VERY DOMESTIC ISSUE High Pay Centre Global CEO appointments: About the High Pay Centre Contents A very domestic issue The High Pay Centre is an The High Pay Centre is resolutely independent non-party think tank independent and strictly non- 4 Foreword established to monitor pay at the partisan. It is increasingly clear that top of the income distribution and there has been a policy and market 5 Executive Summary set out a road map towards better failure in relation to pay at the top business and economic success. of companies and the structures 6 Introduction of business over a period of years We aim to produce high quality under all governments. It is now 7 North America: Staying home research and develop a greater essential to persuade all parties that understanding of top rewards, there is a better way. 9 Western Europe: Trickling across the pond company accountability and business performance. We will The High Pay Centre is grateful to its 12 China: From state to state communicate evidence for change supporters for funding this work. to policymakers, companies and 13 Japan: Decades on a ladder other interested parties to build a @highpaycentre consensus for business renewal. www.highpaycentre.org 14 Rest of Asia: More introspection 15 Eastern Europe: Putin’s boys This report was prepared for 15 Latin America: Impregnable borders the High Pay Centre by David Bolchover. David Bolchover is 16 Conclusion the author of Pay Check: Are Top Earners Really Worth It? and he sits 18 Appendix: Methodology and companies in the study on the advisory board of the High Pay Centre.