Coming Back Home After the Sun Rises: Returnee Entrepreneurs and Growth of High Tech Industries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appointment of Alternate Director

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. (Incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability) Stock Code: 00511 APPOINTMENT OF ALTERNATE DIRECTOR The board of directors (“Board”) of Television Broadcasts Limited (“Company”) is pleased to announce the appointment of Mr. Chen Wen Chi as an Alternate Director to Madam Cher Wang Hsiueh Hong (”Madam Wang”), a Non-executive Director of the Company, effective 13 May 2011. Mr. CHEN Wen Chi Aged 55, has been President and CEO of VIA Technologies, Inc. (“VIA”) since 1992, which offers a comprehensive range of power-efficient PC processor platforms. Mr. Chen’s strong technical background and market insights have enabled VIA to anticipate key industry trends, including the drive for power efficiency and miniaturisation at both the chip and platform levels. In his roles as board directors and advisors, Mr. Chen brings broad industry perspective and business strategy expertise to numerous companies, including HTC Corp. (“HTC”), a developer and manufacturer of some of the most innovative smart phones on the market, and VIA Telecom, Co. Ltd., a major alternative supplier of CDMA processors, as well as a range of IT and new media companies. Mr. Chen also holds seats on several industry advisory bodies, and has been a member of the World Economic Forum for over ten years. -

LIGO Scientists Make First-Ever Observation of Gravity Waves

Stories Firehose All Popular Polls Deals Submit Search Login or Sig1n2 u8p Topics: Devices Build Entertainment Technology Open Source Science YRO Follow us: Slashdot is powered by your submissions, so send in your scoop Nickname: Password: 6-20 characters long Public Terminal Log In Forgot your password? Sign in with Google Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Close Check out the brand new SourceForge HTML5 speed test! Test your internet connection now. Works on all × devices. Second Gravitational Wave Detected From Ancient Black Hole Collision (theguardian.com) Posted by BeauHD on Wednesday June 15, 2016 @11:30PM from the ripples-in-the-fabric-of-spacetime dept. An anonymous reader quotes a report from The Guardian: Physicists have detected ripples in the fabric of spacetime that were set in motion by the collision of two black holes far across the universe more than a billion years ago. The event marks only the second time that scientists have spotted gravitational waves, the tenuous stretching and squeezing of spacetime predicted by Einstein more than a century ago. The faint signal received by the twin instruments of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the US revealed two black holes circling one another 27 times before finally smashing together at half the speed of light. The cataclysmic event saw the black holes, one eight times more massive than the sun, the other 14 times more massive, merge into one about 21 times heavier than the sun. In the process, energy equivalent to the mass of the sun radiated into space as gravitational waves. Writing in the journal Physical Review Letters on Wednesday, the LIGO team describes how a second rush of gravitational waves showed up in their instrument a few months after the first, at 3.38am UK time on Boxing Day morning 2015. -

Book of Abstracts

PICES-2016 25 Year of PICES: Celebrating the Past, Imagining the Future North Pacific Marine Science Organization November 2-13, 2016 San Diego, CA, USA Table of Contents Notes for Guidance � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 5 Venue Floor Plan � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 6 List of Sessions/Workshops � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 9 Meeting Timetable � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 10 PICES Structure � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 12 PICES Acronyms � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 13 Session/Workshop Schedules at a Glance � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 15 List of Posters � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 47 Sessions and Workshops Descriptions � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 63 Abstracts Oral Presentations (ordered by days) � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Vista Procedure

PART C. Hardware Periphery Compatibility 1. Hard Drives 1.1. HDD Devices Type Model HDS721010DLE630 HDS721050DLE630 HDS724040ALE640 HGST HUH728080ALE600 HDN726060ALE610 HDN726040ALE614 ST500DM002 ST1000DM003 ST3000DM001 ST2000DM001 ST1000LM014 ST4000DM000 ST1000DX001 ST2000NM0033 ST1000NX0303 ST2000NX0243 ST6000NM0024 Seagate ST8000AS0002 ST2000DM006 ST500DM009 ST3000DM008 SATA 6G ST10000DM0004 ST6000VX0001 ST1000DX002 ST1000DM010 ST6000DM004 ST8000DM005 ST10000VN004 ST12000DM007 DT01ACA100 TOSHIBA DT01ACA050 HDWE150 WD1003FZEX WD5000AAKX WD30EZRX WD10EALX WD10EZEX WD WD20EFRX WD20EZRZ WD30EFRX WD4001FAEX WD5000AZLX WD2003FZEX EX-B365M-V PAGE 1 Type Model WD20PURX WD10PURX WD60EFRX SATA 6G WD WD60EZRX WD60PURX WD80EFZX WD8002FRYZ SATA 3G Seagate ST31000528AS HGST HTS721010A9E630-4233 TOSHIBA MQ01ABD100-4227 WD20NPVZ-4229 SATA 6G(2.5) WD WD10JPLX-4231 ST1000LX015-4237 Seagate ST2000LM015-4239 1.2. SATA SSD Type Model IS32B-16G ASU800SS-128G-3963 ADATA ASX950SS-240G-4256 SU900-256G-4271 ASX950USS-480G-4369 AMD R3SL120G T1-120G-4342 ANACONDA N2-240G-4348 AST680S-128G AP240GAS720-240G APACER AP240GAS330-240G AP256GAS510SB-256G CSSD-F256GBLX CORSAIR CSSD-F120GBLSB SATA 6G SSD CT250BX100SSD1 CT250MX200SSD1 Crucial CT240BX200SSD1 CT525MX300SSD1 Colorful SL500-640G-4531 FSX-120G FUJITSU F300-240G SSDSC2KW240H6 INTEL SSDSC2BB240G7-4162 KINGBANK KP330-240G-4444 SHSS37A/240G SKC400S37/256G Kingston SUV400S37-240G SA400S37/240GB LITEON MU3-PH4-CE240-240G TRN150-25SAT3-240G TOSHIBA OCZ TL100-25SAT3-240G EX-B365M-V PAGE 2 Type Model PX-256M7VC-256G -

WIC Template 13/9/16 11:52 Am Page IFC1

In a little over 35 years China’s economy has been transformed Week in China from an inefficient backwater to the second largest in the world. If you want to understand how that happened, you need to understand the people who helped reshape the Chinese business landscape. china’s tycoons China’s Tycoons is a book about highly successful Chinese profiles of entrepreneurs. In 150 easy-to- digest profiles, we tell their stories: where they came from, how they started, the big break that earned them their first millions, and why they came to dominate their industries and make billions. These are tales of entrepreneurship, risk-taking and hard work that differ greatly from anything you’ll top business have read before. 150 leaders fourth Edition Week in China “THIS IS STILL THE ASIAN CENTURY AND CHINA IS STILL THE KEY PLAYER.” Peter Wong – Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive, Asia-Pacific, HSBC Does your bank really understand China Growth? With over 150 years of on-the-ground experience, HSBC has the depth of knowledge and expertise to help your business realise the opportunity. Tap into China’s potential at www.hsbc.com/rmb Issued by HSBC Holdings plc. Cyan 611469_6006571 HSBC 280.00 x 170.00 mm Magenta Yellow HSBC RMB Press Ads 280.00 x 170.00 mm Black xpath_unresolved Tom Fryer 16/06/2016 18:41 [email protected] ${Market} ${Revision Number} 0 Title Page.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 6:36 pm Page 1 china’s tycoons profiles of 150top business leaders fourth Edition Week in China 0 Welcome Note.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 3:10 pm Page 2 Week in China China’s Tycoons Foreword By Stuart Gulliver, Group Chief Executive, HSBC Holdings alking around the streets of Chengdu on a balmy evening in the mid-1980s, it quickly became apparent that the people of this city had an energy and drive Wthat jarred with the West’s perception of work and life in China. -

IN THIS ISSUE Saudi Aramco's Khalid A. Al-Falih Gave a Keynote Speech

IN THIS ISSUE Member News Sino-Australian Economic Ties Remain Strong Maintaining China’s Stability is a Top Priority - Resources on Family Business And Why Inflation Isn’t a Problem The Promise of Islamic Finance MAY 2012 Member News Saudi Aramco’s Khalid A. Al-Falih gave a keynote speech at King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals. 3M’s George Buckley was interviewed by the Financial Times. Morris Chang of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. was named Green CEO of the Year at the Top Green Brands awards. SK Group’s Chey Tae-won discussed social enterprises at a meeting preceding the Boao Forum in Hainan, China. Kris Gopalakrishnan of Infosys was interviewed by The Hindu Business Line and The Times of India. Hana Financial Group’s Kim Seung-yu stepped down from his role as Chairman and CEO. Fubon Financial Holding Co.’s Daniel Tsai was named Asia’s Best CEO of Investor Relations by Corporate Governance Asia magazine. He also joined the University of Southern California’s Board of Trustees. Lawson’s Takeshi Niinami outlined his company’s expansion in Asia, particularly China, in an interview with Bloomberg Television. Anand Mahindra of Mahindra & Mahindra discussed Mahindra Research Valley, the company’s new research and development facility, in an interview with The Economic Times. TransUnion’s Penny Pritzker was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. SOHO China’s Zhang Xin shared her thoughts on the Chinese property market in an interview with Bloomberg Television. Ayala Corp.’s Jaime Augusto Zobel de Ayala discussed his company’s strategy to expand its offerings to lower income groups in an interview with Rappler. -

2016-2017 CCKF Annual Report

2016-2017 INTRODUCTION The Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange (the Foundation) was established in 1989 in memory of the outstanding achievements of the late President of the Republic of China, Chiang Ching- kuo (1910-1988). The Foundation’s mission is to promote the study of Chinese culture and society, as well as enhance international scholarly exchange. Its principal work is to award grants and fellowships to institutions and individuals conducting Sinological and Taiwan-related research, thereby adding new life to Chinese cultural traditions while also assuming responsibility for the further development of human civilization. Operational funds supporting the Foundation’s activities derive from interest generated from an endowment donated by both the public and private sectors. As of June 1, 2017, the size of this endowment totaled NT$3.62 billion. The Foundation is governed by its Board of Directors (consisting of between 15 and 21 Board Members), as well as 3 Supervisors. Our central headquarters is located in Taipei, Taiwan, with a regional office near Washington D.C. in McLean, Virginia. In addition, the Foundation currently maintains four overseas centers: the Chiang Ching-kuo International Sinological Center at Charles University in Prague (CCK-ISC); the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation Inter-University Center for Sinology at Harvard University (CCK-IUC); the Chinese University of Hong Kong – Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation Asia-Pacific Centre for Chinese Studies (CCK-APC); and the European Research Center on Contemporary Taiwan – A CCK Foundation Overseas Center at Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen (CCKF-ERCCT). There are also review committees for the five regions covering the geographic scope of the Foundation’s operations: Domestic, American, European, Asia-Pacific and Developing. -

After the Chinese Group Tour Boom 中國團體旅遊熱潮之後

December 2018 | Vol. 48 | Issue 12 THE AMERICAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE IN TAIPEI IN OF COMMERCE THE AMERICAN CHAMBER After the Chinese Group Tour Boom 中國團體旅遊熱潮之後 TAIWAN BUSINESS TOPICS TAIWAN December 2018 | Vol. 48 | Issue 12 Vol. 2018 | December 中 華 郵 政 北 台 字 第 5000 SPECIAL REPORT 號 執 照 登 記 為 雜 誌2019 交 寄 ECONOMIC OUTLOOK Published by the American Chamber Of NT$150 Commerce In Taipei Read TOPICS Online at topics.amcham.com.tw 12_2018_Cover.indd 1 2018/12/9 下午6:55 CONTENTS NEWS AND VIEWS 6 Editorial Don’t Move Backwards on IPR DECEMBER 2018 VOLUME 48, NUMBER 12 7 Taiwan Briefs By Don Shapiro 10 Issues Publisher Higher Rating in World Bank William Foreman Editor-in-Chief Survey Don Shapiro Art Director/ / By Don Shapiro Production Coordinator Katia Chen Manager, Publications Sales & Marketing COVER SECTION Caroline Lee Translation After the Chinese Group Tour Kevin Chen, Yichun Chen, Charlize Hung Boom 中國團體旅遊熱潮之後 By Matthew Fulco 撰文/傅長壽 American Chamber of Commerce in Taipei 129 MinSheng East Road, Section 3, 14 Taiwan’s Hotels Grapple with 7F, Suite 706, Taipei 10596, Taiwan P.O. Box 17-277, Taipei, 10419 Taiwan Oversupply Tel: 2718-8226 Fax: 2718-8182 旅 e-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.amcham.com.tw Although market demand is flat, additional new hotels continue to 050 2718-8226 2718-8182 be constructed. 21 Airbnb on the Brink in Taiwan Business Topics is a publication of the American Taiwan Chamber of Commerce in Taipei, ROC. Contents are independent of and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Changes in regulatory approaches Officers, Board of Governors, Supervisors or members. -

When Drivers Are Not Going to Drive

NOVATEK Microelectronics Co., LTD (3034 TT) When Drivers Are Not Going To Drive National Chengchi University, Taiwan CFA Institute Research Challenge Anna Cheng | Yowen Chang | Jackson Chen | Brian Chien | Yensheng Lee National Chengchi University 1 RECOMMENDATION: SELL 18% 200 (Mar. 31, 2016) 150 NT$ 129.5 TP 100 NT$ 106 50 2015/1/5 2015/4/5 2015/7/5 2015/10/5 2016/1/5 2016/12/31 TV Market Share Erosion Fail to Catch Up with the TDDI Takeoff Limited Contribution from SoC Business National Chengchi University 2 Business & Industry Overview Investment Thesis Financial Analysis & Valuation Investment Risks National Chengchi University 3 Novatek, a Fabless Chip Design Company IC Design Panel End Market Foundry Test Assembly Driver IC SoC Source: AUO, Asus, Sony, Huawei National Chengchi University 4 Display Driver IC, Main Product Line Revenue Breakdown by Product Portfolio 2015 SoC 28% DDIC 72% Source: Company Data National Chengchi University 5 Panel Makers Utilize Novatek’s Products IC Design Panel End Market Foundry Test Assembly Driver IC SoC Source: AUO, Asus, Sony, Huawei National Chengchi University 6 Taiwanese Panel Makers Are Main Customers Revenue Breakdown by Geography, 2015 Japan Taiwan 44% China Korea Source: Company Data National Chengchi University 7 Panels Are Applied to Electronic Products IC Design Panel End Market Foundry Test Assembly Driver IC SoC Source: AUO, Asus, Sony, Huawei National Chengchi University 8 TVs & Smartphones Are Primary Applications Revenue Breakdown by Product, 2015 Tablet Other PC TV 40% Smartphone -

Socioterritorial Fractures in China: the Unachievable “Harmonious Society”?

China Perspectives 2007/3 | 2007 Creating a Harmonious Society Socioterritorial Fractures in China: The Unachievable “Harmonious Society”? Guillaume Giroir Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2073 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.2073 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 septembre 2007 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Guillaume Giroir, « Socioterritorial Fractures in China: The Unachievable “Harmonious Society”? », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2007/3 | 2007, mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2010, consulté le 28 octobre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2073 ; DOI : 10.4000/ chinaperspectives.2073 © All rights reserved Special feature s e Socioterritorial Fractures v i a t c n i in China: The Unachievable e h p s c “Harmonious Society”? r e p GUILLAUME GIROIR This article offers an inventory of the social and territorial fractures in Hu Jintao’s China. It shows the unarguable but ambiguous emergence of a middle class, the successes and failures in the battle against poverty and the spectacular enrichment of a wealthy few. It asks whether the Confucian ideal of a “harmonious society,” which the authorities have been promoting since the early 2000s, is compatible with a market economy. With an eye to the future, it outlines two possible scenarios on how socioterritorial fractures in China may evolve. he need for a “more harmonious society” was raised 1978, Chinese society has effectively ceased to be founded for the first time in 2002 at the Sixteenth Congress on egalitarianism; spatial disparities are to be seen on the T of the Communist Party of China (CPC). -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE HTC REPORTS FIRST QUARTER 2017 RESULTS Taipei, Taiwan – May 9, 2017 – HTC Corporation (TWSE: 2498), a global leader in innovation and design, today announced consolidated results for its fiscal 2017 first quarter ended March 31, 2017. Key figures: • Quarterly revenue of NT$14.5 billion with gross margin of 16.3% • Quarterly operating loss of NT$2.4 billion with operating margin of -16.2% • Quarterly net loss after tax: NT$2.0 billion, or -NT$2.47 per share HTC’s program of realigning resources and streamlining processes continued to reap benefits, recording an opex saving of 20% over the quarter and quarterly gross margin at 16.3%, while maintaining its signature high levels of innovation and quality design and manufacture. All of HTC’s business units demonstrated their innovation prowess in Q1 2017, earning recognition for new product developments. The HTC smartphone division saw the launch of HTC U Ultra and U Play premium smartphones in January. Featuring a 3D ‘liquid surface’, adaptive audio that develops a profile of the user’s ear to tailor sound output, and AI technology in HTC Sense Companion, the HTC U smartphones paved the way for the flagship launch in mid-May. HTC’s VIVE VR division launched the VIVE Tracker™ at CES in January to critical acclaim, with high demand from developers around the world as it enables the easy integration of a new class of accessories into different VR experiences, expanding the ecosystem. The VIVE Tracker won three awards at CES, demonstrating recognition of HTC’s efforts to expand the VR ecosystem. -

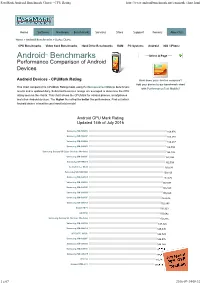

Passmark Android Benchmark Charts - CPU Rating

PassMark Android Benchmark Charts - CPU Rating http://www.androidbenchmark.net/cpumark_chart.html Home Software Hardware Benchmarks Services Store Support Forums About Us Home » Android Benchmarks » Device Charts CPU Benchmarks Video Card Benchmarks Hard Drive Benchmarks RAM PC Systems Android iOS / iPhone Android TM Benchmarks ----Select A Page ---- Performance Comparison of Android Devices Android Devices - CPUMark Rating How does your device compare? Add your device to our benchmark chart This chart compares the CPUMark Rating made using PerformanceTest Mobile benchmark with PerformanceTest Mobile ! results and is updated daily. Submitted baselines ratings are averaged to determine the CPU rating seen on the charts. This chart shows the CPUMark for various phones, smartphones and other Android devices. The higher the rating the better the performance. Find out which Android device is best for your hand held needs! Android CPU Mark Rating Updated 14th of July 2016 Samsung SM-N920V 166,976 Samsung SM-N920P 166,588 Samsung SM-G890A 166,237 Samsung SM-G928V 164,894 Samsung Galaxy S6 Edge (Various Models) 164,146 Samsung SM-G930F 162,994 Samsung SM-N920T 162,504 Lemobile Le X620 159,530 Samsung SM-N920W8 159,160 Samsung SM-G930T 157,472 Samsung SM-G930V 157,097 Samsung SM-G935P 156,823 Samsung SM-G930A 155,820 Samsung SM-G935F 153,636 Samsung SM-G935T 152,845 Xiaomi MI 5 150,923 LG H850 150,642 Samsung Galaxy S6 (Various Models) 150,316 Samsung SM-G935A 147,826 Samsung SM-G891A 145,095 HTC HTC_M10h 144,729 Samsung SM-G928F 144,576 Samsung