John Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Sebastian's Wolf

ISSUE 44 MUSIC EDITION JUNE 25, 2007 John Sebastian’s Wolf: The reason for a “transformation” rather than “A Whole ’Nother Animal” a “tweak” was pure and simple, black and white The original Wolf launched on KPLX/Dallas in July mathematics. The ratings before I got here were the worst 1998. In its short history, it has become one of the most back-to-back monthlies in the history of the Wolf. It didn’t honored, storied and imitated of all need a tweak that might get a three share; it needed a Country stations. Veteran programmer transformation to get back to the four’s and five’s and into John Sebastian was named PD of the a Top 3 position in 25-54 Adults. Cumulus Country outlet in mid-March, The Wolf was beginning to sound too much like and in a very short time has transformed KSCS and going off on some tangents that weren’t very the Wolf into a very different animal than mass-appeal. The station was misaligned, with a lot of architect and original PD Brian Philips promotions, events and concentrated efforts targeted to 18- birthed almost nine years ago. 34s and not 35-44s. Based on my knowledge of successful Country radio, if you don’t win 35-44, you’re dead. And Country Aircheck: What were your first impressions the Wolf was getting slaughtered 35-44. Even though the of the Wolf as you considered taking the PD post? Wolf was beating KSCS 18-34, the [ratings] disparity JS: The music was too safe. -

CNHI Woodstock 20190814

A half-century later, the mother of all music festivals still resonates ifty years after the fact, it still resonates with us. Tucked up in the Catskill Mountains, the Woodstock Music & Art Fair — promoted as “An Aquarian Exposition, Three Days of Peace and Music,” but known to one and all as simply Woodstock — took place in 1969 over three-plus days. From Friday, Aug. 15, through the morning of Monday, Aug. 18, dairy farmer Max Yasgur’s 600- acre parcel of land in Bethel, New York — forever immortalized in Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock” (ironically, she wasn’t at the event itself) — became the epicenter of the music and cultural universe, a haven for 400,000-plus hippies, bohemians, music lovers and mem- bers of the counterculture. It began when folkie Richie Havens began strumming his gui- tar, kicking off the festival with Paul Gerry/Bethel Woods Collection “From the Prison.” Thirty-two more acts, about 66 hours and several rainstorms later, it ended when guitar god Jimi Hendrix capped off a stellar set with his rendition of “Hey Joe.” Thousands of cars were left stranded for miles and miles en route to the venue as concertgo- ers walked to their destination. Tickets for the festival were $18, but many attendees got in for free when the crowd more than tripled what organizers had anticipated. Dallas Taylor, the drummer for supergroup Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (playing just its second-ever show), asked the helicopter pilot James Sarles/Bethel Woods Collection James Sarles/Bethel Woods Collection flying him to the event what body of More than 400,000 people descended on a dairy farm in Bethel, N.Y., for the concert held 50 years ago. -

Bearsville Theater

BEARSVILLE Heartbeat of Woodstock The 15 acre Bearsville site was designed and built by legendary music impresario Albert Grossman in the 1960’s and 70’s. Albert managed Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, The Band and countless other remarkable artists. He chose Bearsville because of its pastoral setting alongside the banks of the Sawkill Creek. He saw Bearsville as a utopian home for his artists to live, write, record, and perform new music in a relaxed bucolic environment, just two hours from NYC. Albert was aided by John Storyk, the architect of acoustic spaces architect who famously designed Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios in NYC. The studios and record label thrived and were successful, even after Albert’s early and Utopia unexpected passing in 1986. Both enterprises have since closed. At the heart of the Center today stands Bearsville Theater, long enjoyed by musicians and music lovers who want to experience the sights and sounds that inspired some of music’s most important writers, singers and performers. Although the Theater opened in 1989, there followed more than 25 years of ownership changes, and the complex never fulfilled Albert’s complete vision. OVERLEAF x BEARSVILLE THEATER 277-297 Tinker Street • Woodstock, NY 12498 BearsvilleTheater.com In 2019 the social entrepreneur Lizzie Vann purchased the Center and began a wholesale renovation, rebuilding Bearsville back into a place for artist development – as Albert wanted it to be. The goal today is to encourage and support future generations of artists, in the same way that Albert saw the need for a whole-person approach to nurturing the creative spirit of his artists. -

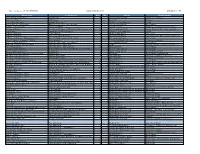

Music Express Song Index V1-V17

John Jacobson's MUSIC EXPRESS Song Index by Title Volumes 1-17 Song Title Contributor Vol. No. Series Theme/Style 1812 Overture (Finale) Tchaikovsky 15 6 Luigi's Listening Lab Listening, Classical 5 Browns, The Brad Shank 6 4 Spotlight Musician A la Puerta del Cielo Spanish Folk Song 7 3 Kodaly in the Classroom Kodaly A la Rueda de San Miguel Mexican Folk Song, John Higgins 1 6 Corner of the World World Music A Night to Remember Cristi Cary Miller 7 2 Sound Stories Listening, Classroom Instruments A Pares y Nones Traditional Mexican Children's Singing Game, arr. 17 6 Let the Games Begin Game, Mexican Folk Song, Spanish A Qua Qua Jerusalem Children's Game 11 6 Kodaly in the Classroom Kodaly A-Tisket A-Tasket Rollo Dilworth 16 6 Music of Our Roots Folk Songs A-Tisket, A-Tasket Folk Song, Tom Anderson 6 4 BoomWhack Attack Boomwhackers, Folk Songs, Classroom A-Tisket, A-Tasket / A Basketful of Fun Mary Donnelly, George L.O. Strid 11 1 Folk Song Partners Folk Songs Aaron Copland, Chapter 1, IWMA John Jacobson 8 1 I Write the Music in America Composer, Classical Ach, du Lieber Augustin Austrian Folk Song, John Higgins 7 2 It's a Musical World! World Music Add and Subtract, That's a Fact! John Jacobson, Janet Day 8 5 K24U Primary Grades, Cross-Curricular Adios Muchachos John Jacobson, John Higgins 13 1 Musical Planet World Music Aeyaya balano sakkad M.B. Srinivasan. Smt. Chandra B, John Higgins 1 2 Corner of the World World Music Africa: Music and More! Brad Shank 4 4 Music of Our World World Music, Article African Ancestors: Instruments from Latin Brad Shank 3 4 Spotlight World Music, Instruments Afro-American Symphony William Grant Still 8 4 Listening Map Listening, Classical, Composer Afro-American Symphony William Grant Still 1 4 Listening Map Listening, Composer Ah! Si Mon Moine Voulait Danser! French-Canadian Folk Song, John Jacobson, John 13 3 Musical Planet World Music Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around African-American Folk Song, arr. -

Omnivore Recordings Releases a Career-Spanning Five-Cd Set Celebrating the Music of Nrbq

OMNIVORE RECORDINGS RELEASES A CAREER-SPANNING FIVE-CD SET CELEBRATING THE MUSIC OF NRBQ November 11 release contains hits, rarities, concert favorites and previously unreleased gems, plus liner notes, ephemera and previously unseen photos. high noon n. : The most advanced, flourishing, or creative stage or period. NRBQ n. : An endlessly creative band on a 50-year high that continually amazes and delights its listeners. BRATTLEBORO, Vt. — There aren’t many bands that have lasted for 50 years, and the list of those still at the top of their creative game is even smaller. High Noon: A 50-Year Retrospective will offer a fascinating look at one of the best. Street date for the set is November 11, 2016. Over the past half century, NRBQ has proven to be a group of peerless and unique musicians, songwriters and performers, continuing to prove it with each new album and live performance. Omnivore Recordings will celebrate this legendary band with the release of High Noon: A 50-Year Retrospective consisting of five CDs of classic recordings all carefully remastered along with many rare and previously unissued gems in an attractive package featuring extensive notes and previously unseen photos. High Noon contains 106 songs and offers a new and fascinating look at a great band, with each disc a unique listening adventure unto itself. The set provides a unique perspective for devoted fans as well as for adventurous newcomers who might only know of NRBQ through other artists’ versions of originals like “Me and the Boys,” “Ridin’ in My Car” and “Christmas Wish” or from hearing their music on TV shows such as The Simpsons, Weeds or Wilfred. -

August 2019 Program Schedule

AUGUST 2019 PROGRAM SCHEDULE 6:30 PM 7:00 PM 7:30 PM 8:00 PM 8:30 PM 9:00 PM 9:30 PM 10:00 PM Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Father Brown Unforgotten Season 1 On Masterpiece Thu. 8/1 Report The Eagle and the Daw Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Washington Open Mind Firing Line with Frontline Fri. 8/2 Report Week Margaret Hoover Left Behind America The Lawrence Impossible Builds Nova Space Men: American Experience Ancient Skies** Sat. 8/3 Welk Show* The Planets: Jupiter 10 Parks That 10 Monuments That Changed Antiques Roadshow The Farthest - Voyager In Space** Sun. 8/4 Changed America* America Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Midsomer Murders Collection On Masterpiece Tunnel: Mon. 8/5 Report A Rare Bird, Part 1 Vengeance** Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Vicious Mum Jamestown Grantchester Tue. 8/6 Report Gym April Episode Seven Season 4 On Masterpiece** Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Death In Paradise 800 Words And Then There Wed. 8/7 Report Episode Five Were None** Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Father Brown Unforgotten Season 2 On Masterpiece Thu. 8/8 Report The Smallest of Things Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Washington Open Mind Firing Line with Frontline Fri. 8/9 Report Week Margaret Hoover Trump's Trade War The Lawrence Impossible Builds Nova To Catch A Comet Ancient Skies** Sat. 8/10 Welk Show* The Planets: Saturn Antiques Janis Joplin: American Masters Woodstock: Three Days That Defined A Generation: Sun. 8/11 Roadshow* American Experience** Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Midsomer Murders Collection On Masterpiece Secrets of Mon. 8/12 Report A Rare Bird, Part 2 Selfridges** Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Vicious Mum Jamestown Grantchester Tue. -

Joe Butler – Lovin' Spoonful 7/26/17, 8�32 PM

Joe Butler – Lovin' Spoonful 7/26/17, 8)32 PM (https://www.lovinspoonful.com/) Joe Butler Since the fifth grade, at ten, Joe Butler has been putting bands together as a singer and musician, turning professional at the age of thirteen (making money at it!) Through Junior High School and High School, he organized several bands playing early Rock and Roll at the Youth Center and for weddings, bar mitzahs, and bars, etc. While in the Air Force, he organized The Kingsmen, the top band on Eastern Long Island in the early ’60s. One of the members of that band was Steve Boone. Joe and Steve continue to be band-mates to this day. After leaving the service in 1963, Joe gathered his band and brought them straight to Greenwich Village, changed the name of the band to The Sellouts, began fronting the band from the drums, singing and playing in clubs, scoring a manager, and securing a Mercury Record contract in less than a month. Streetwise, the joke was “sell-outs” were Folk musicians who’d “gone Rock and Roll”. In fact, this band was the first band to play Folk-Rock anywhere! The Village is where Joe Butler and Steve teamed up with John Sebastian and Zal Yanovsky – and The Lovin’ Spoonful was born! The Spoonful became one of the most popular and influential American bands of the ’60s, creating more than a half a dozen albums as well as soundtrack music for films like Woody Allen’s What’s Up, Tiger Lily?, 1966, and Francis Ford Coppola’s You’re A Big Boy Now, 1967. -

Sizzling 70'S! 14-15 November 2020 Military Madness

SIZZLING 70’S! 14-15 NOVEMBER 2020 MILITARY MADNESS GRAHAM NASH NOWHERE MAN SHERBET LISTEN TO THE MUSIC DOOBIE BROTHERS AMERIKAN MUSIC ALISON DURBIN I HATE THE MUSIC JOHN PAUL YOUNG EVERY TIME I THINK OF YOU THE BABYS THINK ABOUT TOMORROW TODAY MASTER'S APPRENTICES DRAGGIN' THE LINE TOMMY JAMES ROCKET MAN ELTON JOHN LOOK AFTER YOURSELF STARS RICH GIRL HALL & OATES BREAKING UP IS HARD TO DO PARTRIDGE FAMILY YOU ANGEL YOU MANFRED MANN'S EARTH BAND UNCLE ALBERT/ADMIRAL HALSEY PAUL McCARTNEY DECEMBER 1963 (OH WHAT A NIGHT) FOUR SEASONS LOVE ON THE RADIO SKYHOOKS YOU AND ME ALICE COOPER ORCHESTRA LADIES ROSS RYAN LYIN' EYES THE EAGLES FLY ROBIN, FLY SILVER CONVENTION GO YOUR OWN WAY FLEETWOOD MAC 39 QUEEN WHO'LL STOP THE RAIN CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL GYPSY QUEEN COUNTRY RADIO HEART OF GLASS BLONDIE TIN MAN AMERICA JAM UP JELLY TIGHT TOMMY ROE HELP IS ON ITS WAY LITTLE RIVER BAND DARKTOWN STRUTTERS BALL TED MULRY GANG LAST TRAIN TO LONDON ELECTRIC LIGHT ORCHESTRA HOOKED ON A FEELING BLUE SWEDE EVERY NIGHT PHOEBE SNOW HERE WE GO JOHN PAUL YOUNG LAY DOWN SALLY ERIC CLAPTON KONKEROO DRAGON SHILO NEIL DIAMOND LAST TIME I SAW HIM DIANA ROSS LOVE HER MADLY THE DOORS JAMIE COME HOME JAMIE DUNN THE BITCH IS BACK ELTON JOHN THE BOYS ARE BACK IN TOWN THIN LIZZY WELCOME BACK JOHN SEBASTIAN BACK AGAIN STARS YOU'RE THE ONE THAT I WANT OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN/JOHN TRAVOLTA AIN'T GONNA BUMP NO MORE (WITH NO BIG FAT WOMAN) JOE TEX NO MORE MR NICE GUY ALICE COOPER I CAN SEE CLEARLY NOW JOHNNY NASH RIKKI, DON'T LOOSE THAT NUMBER STEELY DAN STAND BY ME JOHN LENNON -

2018–2019 Season

2018–2019 Season AILEY II BILL FRISELL CIRQUE MECHANICS DAN ZANES AND CLAUDIA ELIAZA FEI-FEI, PIANO I’M WITH HER JAKE SHIMABUKURO JD SOUTHER JESSICA LANG DANCE JIMMY WEBB WITH SPECIAL GUEST ASHLEY CAMPBELL JOHN SEBASTIAN KENNY BROBERG, PIANO THE LONE BELLOW MICHAEL FEINSTEIN NICOLE HENRY, SET FOR THE SEASON ON BROADWAY PACIFICO DANCE COMPANY PARKENING INTERNATIONAL GUITAR COMPETITION SHEENA EASTON TOMÁS AND THE LIBRARY LADY VITALY: AN EVENING OF WONDERS WE BANJO 3 YOOJIN JANG, VIOLIN AND MORE! 1 DEAR PATRONS, On behalf of all of us at the Lisa Smith Wengler Center for the Arts, it is my great pleasure to share our 2018–2019 season of performances and exhibitions with you. Whether this is your first time picking up one of our brochures or you are a familiar face at Pepperdine, please know you are welcome here. Our mission is to present an innovative, unique, entertaining, and diverse program of exceptional performances and museum exhibitions. We are grateful for our talented artists, our stunning location, our intimate venues, our President’s Circle sponsors and Center for the Arts Guild members, and you, our loyal and enthusiastic audience. Visit our website to place your order or call our box office and ask our friendly workers for their recommendations—you may just discover your new favorite artist. See you soon at the Center for the Arts! Rebecca Carson and Lisa Smith Wengler at Smothers Theatre Sincerely, Photo by Keith Berson Rebecca Carson Pictured below: Ailey II Pictured on cover: Cirque Mechanics Managing Director TABLE OF CONTENTS PRESIDENT'S CHOICE VIRTUOSI 3 2 Jimmy Webb with Special Guest 2 Fei-Fei, Piano Ashley Campbell 6 Cristina Montes Mateo, Harp and To Be Announced Susan Greenberg Norman, Flute 7 Sheena Easton 6 Jake Shimabukuro WORLD MUSIC AND DANCE 9 Kenny Broberg, Piano 3 Chinese Warriors of Peking 11 YooJin Jang, Violin 5 We Banjo 3 12 Parkening International 4 Guitar Competition 7 Alasdair Fraser and Natalie Haas 8 Dan Zanes and Claudia Eliaza GREGG G. -

Oldiemarkt Journal

EUR 7,10 DIE WELTWEIT GRÖSSTE MONATLICHE 06/08 VINYL -/ CD-AUKTION Juni Earth, Wind & Fire Die Hitmaschine des Marice White Powered and designed by Peter Trieb – D 84453 Mühldorf Ergebnisse der AUKTION 355 Hier finden Sie ein interessantes Gebot dieser Auktion sowie die Auktionsergebnisse Anzahl der Gebote 2.614 Gesamtwert aller Gebote 52.373,00 Gesamtwert der versteigerten Platten / CD’s 22.597,00 Höchstgebot auf eine Platte / CD 408,66 Highlight des Monats Mai 2008 LP - I.D. Company - Inga + Dagmar - Hör zu black - D - M / M So wurde auf die Platte / CD auf Seite 9, Zeile 76 geboten: Mindestgebot EURO 15,00 Die einzige LP der beiden Sängerinnen Bieter 1 - 2 15,00 - 16,18 der in den 60er Jahren enorm erfolgreichen City Preacher um den Iren Bieter 3 - 4 20,10 - 21,56 Brian Docker gehört zu den Raritäten aus der langen Karriere der Inga Rumpf. Bieter 5 27,51 Sie taten sich nach dem Ende ihrer alten Bieter 6 31,87 Band zusammen und nahmen eine Platte auf, die Folk, fernöstliche Musik und Bieter 7 - 9 40,77 - 47,60 deutsche Lieder miteinander verband. Das hatte natürlich keinen großen Erfolg, Bieter 10 78,20 weswegen Inga Rumpf kurz darauf bei Frumpy auftauchte. Während das erste Gebot wie immer nach dem Motto kann man ja mal versuchen abgegeben wurde, sind die Höchstgebote relativ hoch ausgefallen. Bieter 11 79,99 Sie finden Highlight des Monats ab Juni 1998 im Internet unter www.plattensammeln.de Werden Sie reich durch OLDIE-MARKT – die Auktionszahlen sprechen für sich ! Software und Preiskataloge für Musiksammler bei Peter Trieb – D84442 Mühldorf – Fax (+49) 08631 – 162786 – eMail [email protected] Kleinanzeigenformulare WORD und EXCEL im Internet unter www.plattensammeln.de Schallplattenbörsen Oldie-Markt 6/08 3 Plattenbörsen 2008 Schallplattenbörsen sind seit einigen Jahren fester Bestandteil der europäischen Musikszene. -

DSS John Sebastian Custom Signature Edition

DSS John Sebastian Custom Signature Edition Exquisite Sloped Shoulder Dreadnought Edition Honors Lovin’ Spoonful’s John Sebastian John Sebastian’s contributions – both as the leader of-pearl fingerboard position markers are unique: star, cres - of the Lovin’ Spoonful and as a solo artist – loom cent moon and slotted concave diamond markers at the large on the American musical landscape. The unique 5th, 7th and 9th frets. These pay homage to the inlays on fusion of rock, folk and jug band he created with the one of blues icon Mississippi John Hurt’s old guitars. Two Lovin’ Spoonful helped return American popular stars and a slotted concave diamond mark the 12th and music to relevance at the height of the 1960’s “British 15th frets, leading to a mother-of-pearl spoon accented Invasion” and his influence continues to resonate by a red heart between the 19th the 20th frets, symbol - across musical genres. izing the importance of the Lovin’ Spoonful on Sebast - For all his success in the popular realm, Sebastian’s ian's musical career. abiding passion remains roots music; an amalgam of folk, The son of a noted classical harmonica player who blues, country, old time, jug band and more. So when John frequently hosted many folk musicians of the day, among took a serious and intense interest in Chris Marin's most re - them Woody Guthrie and Burl Ives, at the family home in cent "CEO's Choice" model – the CEO-6 – Martin's Dick Boak Greenwich Village, John Sebastian discovered his love for (a long time friend of Sebastian's) initiated the collaboration music early. -

Welcome Back Tab Chords and Lyrics by John Sebastian

http://www.learn-classic-rock-songs.com Welcome Back Tab Chords And Lyrics By John Sebastian Intro – G-A-D … G-A-D Em A7sus A7 D Welcome back - your dreams were your ticket out Em A7sus A7 D Welcome back - To that same old place that you laughed about Gbm B7 Em Well, the names have all changed since you hung around Gm Bm But those dreams have remained and they've turned around Esus E Who'd have thought they'd lead you - (Who'd have thought they'd lead you) A7sus A7 Back here where we need you - (Back here where we need you) Em A7sus A7 D Yeah, we tease him a lot cause we got him on the spot - Welcome back Em A7 D Welcome back - Welcome back, welcome back Em A7 Welcome back, welcome back Em A7sus A7 D Welcome back - We always could spot a friend Em A7sus A7 D Welcome back - And I smile when I think how you must have been Gbm B7 Em And I know what a scene you were learning in Gm Bm Was there something that made you come back again Esus E And what could ever lead you - (What could ever lead you) A7sus A7 Back here where we need you - (Back here where we need you) Em A7sus A7 D Yeah, we tease him a lot cause we got him on the spot - Welcome back Em A7 D Welcome back - Welcome back, welcome back Em A7 Welcome back, welcome back http://www.learn-classic-rock-songs.com http://www.learn-classic-rock-songs.com Break - Em – A7sus – A7 – D – Em –A7 - D Gbm B7 Em And I know what a scene you were learning in Gm Bm Was there something that made you come back again Esus E And what could ever lead you - (What could ever lead you) A7sus A7 Back here where