I UNIVERSITY of OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deep Background: Journalists, Sources, and the Perils of Leaking William E

American University Law Review Volume 57 | Issue 5 Article 8 2008 Deep Background: Journalists, Sources, and the Perils of Leaking William E. Lee Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Lee, William E. “Deep Background: Journalists, Sources, and the Perils of Leaking.” American University Law Review 57, no.5 (June 2008): 1453-1529. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Deep Background: Journalists, Sources, and the Perils of Leaking Keywords Journalists, Press, Leakers, Leak Investigations, Duty of Nondisclosure, Duty of Confidentiality, Prosecutions, Classified information, First Amendment, Espionage Act This article is available in American University Law Review: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol57/iss5/8 DEEP BACKGROUND: JOURNALISTS, SOURCES, AND THE PERILS OF LEAKING ∗ WILLIAM E. LEE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.......................................................................................1454 I. Leaking, Leak Investigations, and the Duty of Nondisclosure..........................................................................1462 -

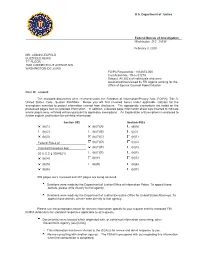

Buzzfeed FOIA Release of Mueller Report FBI 302 Reports

86'HSDUWPHQWRI-XVWLFH )HGHUDO%XUHDXRI,QYHVWLJDWLRQ Washington, D.C. 20535 )HEUXDU\ 05-$621/(232/' %8==)(('1(:6 7+)/225 &211(&7,&87$9(18(1: :$6+,1*721'& )2,3$5HTXHVW1R &LYLO$FWLRQ1RFY 6XEMHFW$OO¶VRILQGLYLGXDOVZKRZHUH TXHVWLRQHGLQWHUYLHZHGE\)%,$JHQWVZRUNLQJIRUWKH 2IILFHRI6SHFLDO&RXQVHO5REHUW0XHOOHU 'HDU0U/HRSROG 7KH HQFORVHG GRFXPHQWV ZHUH UHYLHZHG XQGHU WKH )UHHGRP RI ,QIRUPDWLRQ3ULYDF\$FWV )2,3$ 7LWOH 8QLWHG 6WDWHV &RGH 6HFWLRQ D %HORZ \RX ZLOO ILQG FKHFNHG ER[HV XQGHU DSSOLFDEOH VWDWXWHV IRU WKH H[HPSWLRQVDVVHUWHGWRSURWHFWLQIRUPDWLRQH[HPSWIURPGLVFORVXUH 7KHDSSURSULDWHH[HPSWLRQVDUHQRWHGRQWKH SURFHVVHGSDJHVQH[WWRUHGDFWHGLQIRUPDWLRQ ,QDGGLWLRQDGHOHWHGSDJHLQIRUPDWLRQVKHHWZDVLQVHUWHGWRLQGLFDWH ZKHUHSDJHVZHUHZLWKKHOGHQWLUHO\SXUVXDQWWRDSSOLFDEOHH[HPSWLRQV $Q([SODQDWLRQRI([HPSWLRQVLVHQFORVHGWR IXUWKHUH[SODLQMXVWLILFDWLRQIRUZLWKKHOGLQIRUPDWLRQ 6HFWLRQ 6HFWLRQD E E $ G E E % M E E & N E ' N )HGHUDO5XOHVRI E ( N &ULPLQDO3URFHGXUH H E ) N 86& L E E N E E N E N SDJHVZHUHUHYLHZHGDQGSDJHVDUHEHLQJUHOHDVHG 'HOHWLRQVZHUHPDGHE\WKH'HSDUWPHQWRI-XVWLFH2IILFHRI,QIRUPDWLRQ3ROLF\7RDSSHDOWKRVH GHQLDOVSOHDVHZULWHGLUHFWO\WRWKDWDJHQF\ 'HOHWLRQVZHUHPDGHE\WKH'HSDUWPHQWRI-XVWLFH([HFXWLYH2IILFHIRU8QLWHG6WDWHV$WWRUQH\V7R DSSHDOWKRVHGHQLDOVSOHDVHZULWHGLUHFWO\WRWKDWDJHQF\ 3OHDVHVHHWKHSDUDJUDSKVEHORZIRUUHOHYDQWLQIRUPDWLRQVSHFLILFWR\RXUUHTXHVWDQGWKHHQFORVHG)%, )2,3$$GGHQGXPIRUVWDQGDUGUHVSRQVHVDSSOLFDEOHWRDOOUHTXHVWV 'RFXPHQW V ZHUHORFDWHGZKLFKRULJLQDWHGZLWKRUFRQWDLQHGLQIRUPDWLRQFRQFHUQLQJRWKHU *RYHUQPHQW$JHQF\ -

Supreme Court Spinners

Lobbying&Law Supreme Court Spinners By Bara Vaida hen Mark Corallo opened that includes Apple Computer, Intel, Mi- I What’s Washington’s latest his copy of The New York crosoft, Micron Technology, and Oracle, PR trend? It’s pitching reporters Times on March 28, the supported eBay’s position challenging street-smart Republican spin the appeals court’s ruling. on Supreme Court cases. Wdoctor did a little touchdown dance. Corallo says his communications firm, The paper had published an editorial Corallo Media Strategies, was hired to ex- I Experts say that strong media supporting the legal position of several plain eBay’s position and garner media of Corallo’s clients in a high-tech patent attention because “the justices read the coverage can influence the case before the Supreme Court. newspapers.” Former Justice Sandra Day justices and their clerks. The editorial appeared the day before O’Connor was the best example of that, the case was to be argued, and it came af- he says, noting that during oral arguments ter weeks of work by a team of lawyers and she would ask the dueling lawyers, I Some practitioners shy away consultants that included the 40-year-old “‘Where are the people?’ on issues of law.” Corallo, a former Justice Department Corallo’s confidence that the nine jus- from talking about their work. spokesman. The many phone calls to re- tices and their clerks pay attention to porters and newspaper editorial boards what the media say about cases chal- explaining the case—in which a small Vir- lenges conventional wisdom. -

Investigation Into Allegations of Justice Department Misconduct in New England—Volume 1

INVESTIGATION INTO ALLEGATIONS OF JUSTICE DEPARTMENT MISCONDUCT IN NEW ENGLAND—VOLUME 1 HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST AND SECOND SESSIONS MAY 3; DECEMBER 13, 2001; AND FEBRUARY 6, 2002 Serial No. 107–56 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/congress/house http://www.house.gov/reform VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:07 May 30, 2002 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\78051.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:07 May 30, 2002 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\78051.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 INVESTIGATION INTO ALLEGATIONS OF JUSTICE DEPARTMENT MISCONDUCT IN NEW ENGLAND—VOLUME 1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:07 May 30, 2002 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 C:\DOCS\78051.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:07 May 30, 2002 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 C:\DOCS\78051.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 INVESTIGATION INTO ALLEGATIONS OF JUSTICE DEPARTMENT MISCONDUCT IN NEW ENGLAND—VOLUME 1 HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST AND SECOND SESSIONS MAY 3; DECEMBER 13, 2001; AND FEBRUARY 6, 2002 Serial No. 107–56 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/congress/house http://www.house.gov/reform U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 78–051 PDF WASHINGTON : 2001 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

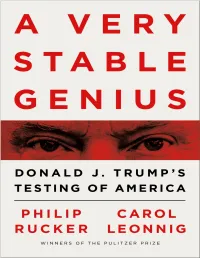

A Very Stable Genius at That!” Trump Invoked the “Stable Genius” Phrase at Least Four Additional Times

PENGUIN PRESS An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2020 by Philip Rucker and Carol Leonnig Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019952799 ISBN 9781984877499 (hardcover) ISBN 9781984877505 (ebook) Cover design by Darren Haggar Cover photograph: Pool / Getty Images btb_ppg_c0_r2 To John, Elise, and Molly—you are my everything. To Naomi and Clara Rucker CONTENTS Title Page Copyright Dedication Authors’ Note Prologue PART ONE One. BUILDING BLOCKS Two. PARANOIA AND PANDEMONIUM Three. THE ROAD TO OBSTRUCTION Four. A FATEFUL FIRING Five. THE G-MAN COMETH PART TWO Six. SUITING UP FOR BATTLE Seven. IMPEDING JUSTICE Eight. A COVER-UP Nine. SHOCKING THE CONSCIENCE Ten. UNHINGED Eleven. WINGING IT PART THREE Twelve. SPYGATE Thirteen. BREAKDOWN Fourteen. ONE-MAN FIRING SQUAD Fifteen. CONGRATULATING PUTIN Sixteen. A CHILLING RAID PART FOUR Seventeen. HAND GRENADE DIPLOMACY Eighteen. THE RESISTANCE WITHIN Nineteen. SCARE-A-THON Twenty. AN ORNERY DIPLOMAT Twenty-one. GUT OVER BRAINS PART FIVE Twenty-two. AXIS OF ENABLERS Twenty-three. LOYALTY AND TRUTH Twenty-four. THE REPORT Twenty-five. THE SHOW GOES ON EPILOGUE Acknowledgments Notes Index About the Authors AUTHORS’ NOTE eporting on Donald Trump’s presidency has been a dizzying R journey. Stories fly by every hour, every day. -

Evidentiary Privileges Can Do Little to Block Trump-Related Investigations

Evidentiary Privileges Can Do Little to Block Trump-Related Investigations Norman L. Eisen and Andrew M. Wright1 June 29, 2018 1 Norman L Eisen is a Senior Fellow at The Brookings Institution and served as President Barack Obama's “ethics czar” and as U.S Ambassador to the Czech Republic. He is also the co-founder and Chair of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW). Andrew M. Wright is Associate Professor, Savannah Law School. He previously served as Former Associate Counsel to President Barack Obama, Assistant Counsel to Vice President Al Gore, and Staff Director/Counsel to the Subcommittee on National Security & Foreign Affairs of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. This report was prepared for the Presidential Investigation Education Project, a joint initiative by ACS and CREW to promote informed public evaluation of the investigations by Special Counsel Robert Mueller and others into Russian interference in the 2016 election and related matters. This effort includes developing and disseminating legal analysis of key issues that emerge as the inquiries unfold and connecting members of the media and public with ACS and CREW experts and other legal scholars who are writing on these matters. The authors would like to thank Kristin Amerling, Conor Shaw, Maya Gold, and Eden Tadesse for their contributions to this report. Table of Contents I. Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 3 II. Executive Privilege: A Contested Doctrine..................................................................... 5 A. Executive Privilege Issues in the Russia Investigations to Date ..............................5 B. The Process: Executive Privilege Requires a Presidential Act ................................7 III. Executive Privilege Components ..................................................................................... 9 A. Presidential Communications ..................................................................................9 B. -

Expedited Treatment Requested

VIA FEDERAL EXPRESS EXPEDITED TREATMENT REQUESTED September 18, 2017 Hon. Beryl Howell Chief Judge U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia 333 Constitution Ave, NW Washington, D.C. 20001 Hon. Rebecca Beach Smith Chief Judge U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia 600 Granby Street Norfolk, VA, 23510 RE: COMPLAINT AGAINST SPECIAL COUNSEL ROBERT MUELLER AND STAFF AND REQUEST FOR EXPEDITED INVESTIGATION AND EVIDENTIARY HEARING INTO GROSS PROSECUTORIAL MISCONDUCT OF PROSECUTING ATTORNEYS Dear Chief Judge Howell and Chief Judge Smith: Freedom Watch and I are forwarding this letter with attachments in the public’s interest.1 The undersigned General Counsel of Freedom Watch submits this as a former prosecutor in the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division and the founder and former chairman of Judicial Watch, as well as the founder, chairman, and general counsel of 1 The undersigned counsel made efforts to obtain docket information from the clerks of the respective courts, but was unable to obtain this information. The undersigned counsel was informed by the clerks that this information is secret, which is ironic and telling, given the fact that little to anything else related the substance of the grand jury proceedings are being kept secret by Special Counsel Robert Mueller and his staff. Ethics Investigation Request: Robert Mueller Page | 3 Washington, DC 20530 Hon. Michael E. Horowitz Inspector General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Ave, NW, #4706 Washington, DC 20530 Hon. Jeff Sessions Attorney General of the United States U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Ave, NW Washington, DC, 20530 Hon. -

Anthrax in America: a Chronology and Analysis of the Fall 2001 Attacks

Working Paper Anthrax In America: A Chronology and Analysis of the Fall 2001 Attacks November 2002 Center for Counterproliferation National Defense University Research Washington, DC The opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the Center for Counterproliferation Research, and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or any other U.S. Government agency. This publication is cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without further permission, with credit to the Center for Counterproliferation Research, National Defense University. For additional information, please contact the Center directly or visit the Center’s website at http://www.ndu.edu/centercounter/index.htm ii Anthrax in America Executive Summary Introduction On September 11, 2001, terrorists linked to Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda terror network hijacked four airliners. Two of the planes crashed into the World Trade Center towers in New York City, and a third into the Pentagon in Washington, DC. A fourth plane crashed in rural Pennsylvania en route to its suspected target, the U.S. Capitol building. The attacks and their dramatic demonstration of American vulnerability created an atmosphere of apprehension and uncertainty. Further attacks were anticipated, although there was a great deal of uncertainty as to when those attacks might occur and what form they might take. Against this backdrop, on 4 October 2001, health officials in Florida announced that Robert Stevens, a tabloid photo editor at American Media, Inc. (AMI), had been diagnosed with pulmonary anthrax – the first such case in the United States in almost twenty-five years. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA ___Steven J. HATFILL, MD, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) V

Case 1:03-cv-01793-RBW Document 229-2 Filed 04/11/2008 Page 1 of 40 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA _____________ Steven J. HATFILL, M.D., ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil No. 1:03-CV-01793 (RBW) ) Attorney General Michael MUKASEY, ) et al., ) ) Defendants. ) ___________________________________ ) PLAINTIFF’S MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT April 11, 2007 HARRIS, WILTSHIRE & GRANNIS, LLP Thomas G. Connolly, D.C. Bar # 420416 Mark A. Grannis, D.C. Bar # 429268 Patrick O’Donnell, D.C. Bar # 459360 1200 Eighteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 Telephone: (202) 730-1300 Facsimile: (202) 730-1301 Case 1:03-cv-01793-RBW Document 229-2 Filed 04/11/2008 Page 2 of 40 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY JUDGMENT STANDARD .................................................................................... 6 ARGUMENT................................................................................................................................. 6 I. THE AGENCY DEFENDANTS VIOLATED THE SAFEGUARDING, INSTRUCTION, AND ACCOUNTING PROVISIONS OF THE PRIVACY ACT....................................................................... 6 A. The Investigative Disclosures in this Case Reflect "Records" Contained Within a "System of Records" ......................... 8 B. The Agency Defendants Failed to Safeguard Investigative Records About Dr. Hatfill -

Presidential Obstruction of Justice: the Case of Donald J. Trump

PRESIDENTIAL OBSTRUCTION OF JUSTICE: THE CASE OF DONALD J. TRUMP 2ND EDITION AUGUST 22, 2018 BARRY H. BERKE, NOAH BOOKBINDER, AND NORMAN L. EISEN* * Barry H. Berke is co-chair of the litigation department at Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP (Kramer Levin) and a fellow of the American College of Trial Lawyers. He has represented public officials, professionals and other clients in matters involving all aspects of white-collar crime, including obstruction of justice. Noah Bookbinder is the Executive Director of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW). Previously, Noah has served as Chief Counsel for Criminal Justice for the United States Senate Judiciary Committee and as a corruption prosecutor in the United States Department of Justice’s Public Integrity Section. Ambassador (ret.) Norman L. Eisen, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, was the chief White House ethics lawyer from 2009 to 2011 and before that, defended obstruction and other criminal cases for almost two decades in a D.C. law firm specializing in white-collar matters. He is the chair and co-founder of CREW. We are grateful to Sam Koch, Conor Shaw, Michelle Ben-David, Gabe Lezra, and Shaked Sivan for their invaluable assistance in preparing this report. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. -

Building a Better Mousetrap: Patenting Biotechnology In

ENACTING A REASONABLE FEDERAL SHIELD LAW: A REPLY TO PROFESSORS CLYMER AND ELIASON ∗ JAMES THOMAS TUCKER ∗∗ STEPHEN WERMIEL “[W]ithout some protection for seeking out the news, freedom of the press could be eviscerated.” Justice Byron White1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.......................................................................................1292 I. Promoting an Informed Electorate Through a Free Press ...1294 II. The Need for a Federal Shield Law: Branzburg and Its Aftermath.................................................................................1297 A. The Branzburg Decision ....................................................1298 B. State Responses to Branzburg and Nixon’s Abuse of Power.................................................................................1301 C. The Hodge-Podge of Federal Responses to Branzburg ...1303 1. Federal Rule of Evidence 501 does not recognize a common law shield ..................................................1303 2. Department of Justice regulations are inadequate ...1304 3. Federal courts are divided over the journalist shield’s scope ..............................................................1307 ∗ First Amendment Policy Counsel, American Civil Liberties Union, Washington Legislative Office; S.J.D., University of Pennsylvania, 2001; LL.M., University of Pennsylvania, 1998; J.D., University of Florida, 1994. ∗∗ Adjunct Professor of Law, American University, Washington College of Law; J.D., American University, Washington College of Law, 1982; B.A., Tufts University, -

Ashcroft Attacks Librarians Over Patriot

ISSN 0028-9485 November 2003 Volume LII No. 6 www.ala.org/nif Attorney General John Ashcroft accused the American Library Association and other critics of the USA PATRIOT Act September 16 of fueling ‘‘baseless hysteria’’ about the government’s ability to pry into the public’s reading habits. In an unusually pointed attack as part of a speech in defense of the Bush administration’s counterterrorism initiatives delivered in Memphis, Tennessee, Ashcroft mocked and condemned the ALA and other Justice Department critics for believing that the F.B.I. wants to know ‘‘how far you have gotten on the latest Tom Clancy novel.’’ ‘‘If he’s coming after us so specifically, we must be having an impact,’’ said Emily Sheketoff, executive director of ALA’s Washington office. Ashcroft Mark Corallo, a spokesman for the department, said the speech was intended not as an attack on librarians, but on groups like the American Civil Liberties Union and politicians attacks who he said had persuaded librarians to mistrust the government. The ALA ‘‘has been somewhat duped by those who are ideologically opposed to the Patriot Act,’’ Corallo said. Ashcroft’s remarks, he said, ‘‘should be seen as a jab at those who would mislead librarians librarians and the general public into believing the absurd, that the F.B.I. is running around monitoring libraries instead of going after terrorists.’’ over Patriot ALA President Carla Hayden responded to Ashcroft in a prepared statement, which read: Act “The American Library Association (ALA) has worked diligently for the past two years to increase awareness of a very complicated law—the USA PATRIOT Act—that was pushed through the legislative process at breakneck speed in the wake of a national tragedy.