Māori Oral Traditions Record and Convey Indigenous Knowledge Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reef Fish Monitoring Te Tapuwae O Rongokako Marine Reserve

Reef Fish Monitoring Te Tapuwae o Rongokako Marine Reserve Technical Support - Marine East Coast Hawke’s Bay Conservancy Debbie Freeman OCTOBER 2005 Published By Department of Conservation East Coast Hawkes Bay Conservancy PO Box 668 Gisborne 4040, New Zeland Cover: Banded wrasse Photo: I. Nilsson Title page: Koheru Photo: M. Blackwell Acknowledgments: Blue maomao Photo: J. Quirk © Copyright October 2005, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1175-026X ISBN 978-0-478-14143-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-0-478-14193-1 (Web pdf) Techincal Support Series Number: 25 In the interest of forest conservation, DOC Science Publishing supports paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. C ontents Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Methods 6 Results 10 Discussion 20 Fish fauna 20 Protection effects 21 Reserve age and design 21 Experimental design and monitoring methods 22 Illegal fishing 23 Environmental factors 24 Acknowledgements 24 References 25 Abstract Reef fish monitoring was undertaken within and surrounding Te Tapuwae o Rongokako Marine Reserve, on the North Island’s East Coast, between 2000 and 2004. The objective of the monitoring was to describe the reef fish communities and to establish whether populations within the marine reserve were demonstrating any changes in abundance or size that could be attributable to the removal of fishing pressure. The underwater visual census method was used to survey the four lo- cations (marine reserve and three non-reserve locations). It was found that all four locations were characterised by moderate densities of spot- ties, scarlet wrasse and reef-associated planktivores such as blue maomao, sweep and butterfly perch. -

To Next File: Sfc260a.Pdf

Appendix 1 FISH SPECIES IDENTIFIED FROM THE COASTAL EAST CAPE REGION Surveys of the East Cape Region (Bay of Plenty and East Coast) were conducted during 1992, 1993, and 1999 (see Tables 1, 2, and 4 for locality data), with additional records from the National Fish Collection. FAMILY, SPECIES, AND AUTHORITY COMMON NAME STATIONS Lamnidae Isurus oxyrinchus Rafinesque mako shark (P) E20o Squalidae Squalus mitsukurii Jordon & Snyder piked spurdog (D) W Dasyatidae Dasyatis brevicaudata (Hutton) shorttailed stingray E19o Myliobatidae eMyliobatis tenuicaudatus (Hector) eagle ray E03° Anguillidae Anguilla australis Richardson shortfin eel (F) W eAnguilla dieffenbachii Gray longfin eel (F) W Muraenidae Gymnothorax prasinus (Richardson) yellow moray E05o, E08° Ophichthyidae Scolecenchelys australis (MacLeay) shortfinned worm eel E01, E10, E11, E28, E29, E33, E48 Congridae Conger verreauxi Kaup southern conger eel E03, E07, E09, E12°, E13, E16, E18, E22o, E23o, E25o, E31, E33 Conger wilsoni (Bloch & Schneider) northern conger eel W; E05, E09, E12, E27 Conger sp. conger E01°, E31o Engraulidae Engraulis australis (White) anchovy (P) E Clupeidae Sardinops neopilchardus (Steindachner) pilchard (P) E Gonorynchidae Gonorynchus forsteri Ogilby sandfish (D) E Retropinnidae eRetropinna retropinna (Richardson) smelt (F) W; E Galaxiidae Galaxias maculatus (Jenyns) inanga (F) W; E Bythitidae eBidenichthys beeblebroxi Paulin grey brotula E01, E03, E08, E09, E10, E12, E18, E19, E21, E23, E27, E28, E29, E31, E33, E34 eBrosmodorsalis persicinus Paulin & Roberts pink brotula E02, E07, E10°, E18, E22, E29, E31, E33o eDermatopsis macrodon Ogilby fleshfish E08, E31 Moridae Austrophycis marginata (Günther) dwarf cod (D) E Continued next page > e = NZ endemic species. D = deepwater species (> 50 m depth); E = estuarine species; F = freshwater species; P = pelagic species; U = species of uncertain identity. -

A Checklist of Fishes of the Aldermen Islands, North-Eastern New Zealand, with Additions to the Fishes of Red Mercury Island

13 A CHECKLIST OF FISHES OF THE ALDERMEN ISLANDS, NORTH-EASTERN NEW ZEALAND, WITH ADDITIONS TO THE FISHES OF RED MERCURY ISLAND by Roger V. Grace* SUMMARY Sixty-five species of marine fishes are listed for the Aldermen Islands, and additions made to an earlier list for Red Mercury Island (Grace, 1972), 35 km to the north. Warm water affinities of the faunas are briefly discussed. INTRODUCTION During recent years, and particularly the last four years, over 30 species of fishes have been added to the New Zealand fish fauna through observation by divers, mainly at the Poor Knights Islands (Russell, 1971; Stephenson, 1970, 1971; Doak, 1972; Whitley, 1968). A high proportion of the fishes of northern New Zealand have strong sub-tropical affinities (Moreland, 1958), and there is considerable evidence (Doak, 1972) to suggest that many of the recently discovered species are new arrivals from tropical and subtropical areas. These fishes probably arrive as eggs or larvae, carried by favourable ocean currents, and find suitable habitats for their development at the Poor Knights Islands, where the warm currents that transported the young fish or eggs maintain a water temperature higher than that on the adjacent coast, or islands to the south. Unless these fishes are able to establish breeding populations in New Zealand waters, they are likely to be merely transient. If they become established, they may begin to spread and colonise other off-shore islands and the coast. In order to monitor any spreading of new arrivals, or die-off due to inability to breed, it is desirable to compile a series of fish lists, as complete as possible, for the off-shore islands of the north-east coast of New Zealand. -

Multiple Measures of Thermal Performance of Early Stage Eastern Rock Lobster in a Fast-Warming Ocean Region

Vol. 624: 1–11, 2019 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published August 15 https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13054 Mar Ecol Prog Ser OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS FEATURE ARTICLE Multiple measures of thermal performance of early stage eastern rock lobster in a fast-warming ocean region Samantha Twiname1,*, Quinn P. Fitzgibbon1, Alistair J. Hobday2, Chris G. Carter1, Gretta T. Pecl1 1Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 49, Hobart, TAS 7001, Australia 2CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, Castray Esplanade, Hobart, TAS 7001, Australia ABSTRACT: To date, many studies trying to under- stand species’ climate-driven changes in distribution, or ‘range shifts’, have each focused on a single poten- tial mechanism. While a single performance measure may give some insight, it may not be enough to ac - curately predict outcomes. Here, we used multiple measures of performance to explore potential mech- anisms behind species range shifts. We examined the thermal pattern for multiple measures of performance, including measures of aerobic metabolism and multi- ple as pects of escape speed, using the final larval stage (puerulus) of eastern rock lobster Sagmariasus verreauxi as a model species. We found that aerobic scope and escape speed had different thermal per- Single thermal performance measures for eastern rock lob- formances and optimal temperatures. The optimal ster Sagmariasus verreauxi may not accurately predict whole temperature for aerobic scope was 27.5°C, while the animal performance under future ocean warming. pseudo-optimal temperature for maximum escape Photo: Peter Mathew speed was 23.2°C. This discrepancy in thermal per- formance indicators illustrates that one measure of performance may not be sufficient to accurately pre- 1. -

AEBR 114 Review of Factors Affecting the Abundance of Toheroa Paphies

Review of factors affecting the abundance of toheroa (Paphies ventricosa) New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 114 J.R. Williams, C. Sim-Smith, C. Paterson. ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-0-478-41468-4 (online) June 2013 Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries websites at: http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-resources/publications.aspx http://fs.fish.govt.nz go to Document library/Research reports © Crown Copyright - Ministry for Primary Industries TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 2 2. METHODS ....................................................................................................................... 3 3. TIME SERIES OF ABUNDANCE .................................................................................. 3 3.1 Northland region beaches .......................................................................................... 3 3.2 Wellington region beaches ........................................................................................ 4 3.3 Southland region beaches ......................................................................................... -

Ripiro Beach

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. The modification of toheroa habitat by streams on Ripiro Beach A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Research) in Environmental Science at The University of Waikato by JANE COPE 2018 ―We leave something of ourselves behind when we leave a place, we stay there, even though we go away. And there are things in us that we can find again only by going back there‖ – Pascal Mercier, Night train to London i Abstract Habitat modification and loss are key factors driving the global extinction and displacement of species. The scale and consequences of habitat loss are relatively well understood in terrestrial environments, but in marine ecosystems, and particularly soft sediment ecosystems, this is not the case. The characteristics which determine the suitability of soft sediment habitats are often subtle, due to the apparent homogeneity of sandy environments. -

Phylum MOLLUSCA Chitons, Bivalves, Sea Snails, Sea Slugs, Octopus, Squid, Tusk Shell

Phylum MOLLUSCA Chitons, bivalves, sea snails, sea slugs, octopus, squid, tusk shell Bruce Marshall, Steve O’Shea with additional input for squid from Neil Bagley, Peter McMillan, Reyn Naylor, Darren Stevens, Di Tracey Phylum Aplacophora In New Zealand, these are worm-like molluscs found in sandy mud. There is no shell. The tiny MOLLUSCA solenogasters have bristle-like spicules over Chitons, bivalves, sea snails, sea almost the whole body, a groove on the underside of the body, and no gills. The more worm-like slugs, octopus, squid, tusk shells caudofoveates have a groove and fewer spicules but have gills. There are 10 species, 8 undescribed. The mollusca is the second most speciose animal Bivalvia phylum in the sea after Arthropoda. The phylum Clams, mussels, oysters, scallops, etc. The shell is name is taken from the Latin (molluscus, soft), in two halves (valves) connected by a ligament and referring to the soft bodies of these creatures, but hinge and anterior and posterior adductor muscles. most species have some kind of protective shell Gills are well-developed and there is no radula. and hence are called shellfish. Some, like sea There are 680 species, 231 undescribed. slugs, have no shell at all. Most molluscs also have a strap-like ribbon of minute teeth — the Scaphopoda radula — inside the mouth, but this characteristic Tusk shells. The body and head are reduced but Molluscan feature is lacking in clams (bivalves) and there is a foot that is used for burrowing in soft some deep-sea finned octopuses. A significant part sediments. The shell is open at both ends, with of the body is muscular, like the adductor muscles the narrow tip just above the sediment surface for and foot of clams and scallops, the head-foot of respiration. -

New Zealand Fishes a Field Guide to Common Species Caught by Bottom, Midwater, and Surface Fishing Cover Photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola Lalandi), Malcolm Francis

New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing Cover photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola lalandi), Malcolm Francis. Top left – Snapper (Chrysophrys auratus), Malcolm Francis. Centre – Catch of hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae), Neil Bagley (NIWA). Bottom left – Jack mackerel (Trachurus sp.), Malcolm Francis. Bottom – Orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), NIWA. New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No: 208 Prepared for Fisheries New Zealand by P. J. McMillan M. P. Francis G. D. James L. J. Paul P. Marriott E. J. Mackay B. A. Wood D. W. Stevens L. H. Griggs S. J. Baird C. D. Roberts‡ A. L. Stewart‡ C. D. Struthers‡ J. E. Robbins NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Wellington 6241 ‡ Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, 6011Wellington ISSN 1176-9440 (print) ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-1-98-859425-5 (print) ISBN 978-1-98-859426-2 (online) 2019 Disclaimer While every effort was made to ensure the information in this publication is accurate, Fisheries New Zealand does not accept any responsibility or liability for error of fact, omission, interpretation or opinion that may be present, nor for the consequences of any decisions based on this information. Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries website at http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-and-resources/publications/ A higher resolution (larger) PDF of this guide is also available by application to: [email protected] Citation: McMillan, P.J.; Francis, M.P.; James, G.D.; Paul, L.J.; Marriott, P.; Mackay, E.; Wood, B.A.; Stevens, D.W.; Griggs, L.H.; Baird, S.J.; Roberts, C.D.; Stewart, A.L.; Struthers, C.D.; Robbins, J.E. -

Goldstein Et Al 2019

Journal of Crustacean Biology Advance Access published 24 August 2019 Journal of Crustacean Biology The Crustacean Society Journal of Crustacean Biology 39(5), 574–581, 2019. doi:10.1093/jcbiol/ruz055 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcb/article-abstract/39/5/574/5554142/ by University of New England Libraries user on 04 October 2019 Development in culture of larval spotted spiny lobster Panulirus guttatus (Latreille, 1804) (Decapoda: Achelata: Palinuridae) Jason S. Goldstein1, Hirokazu Matsuda2, , Thomas R. Matthews3, Fumihiko Abe4, and Takashi Yamakawa4, 1Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve, Maine Coastal Ecology Center, 342 Laudholm Farm Road, Wells, ME 04090 USA; 2Mie Prefecture Fisheries Research Institute, 3564-3, Hamajima, Shima, Mie 517-0404 Japan; 3Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, 2796 Overseas Hwy, Suite 119, Marathon, FL 33050 USA; and 4Department of Aquatic Bioscience, Graduate School of Agricultual and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo, 1-1-1 Yayoi, Bunkyo, Tokyo 113-8657 Japan HeadA=HeadB=HeadA=HeadB/HeadA Correspondence: J.S. Goldstein: e-mail: [email protected] HeadB=HeadC=HeadB=HeadC/HeadB (Received 15 May 2019; accepted 11 July 2019) HeadC=HeadD=HeadC=HeadD/HeadC Ack_Text=DisHead=Ack_Text=HeadA ABSTRACT NList_lc_rparentheses_roman2=Extract1=NList_lc_rparentheses_roman2=Extract1_0 There is little information on the early life history of the spotted spiny lobster Panulirus guttatus (Latreille, 1804), an obligate reef resident, despite its growing importance as a fishery re- BOR_HeadA=BOR_HeadB=BOR_HeadA=BOR_HeadB/HeadA source in the Caribbean and as a significant predator. We cultured newly-hatched P. guttatus BOR_HeadB=BOR_HeadC=BOR_HeadB=BOR_HeadC/HeadB larvae (phyllosomata) in the laboratory for the first time, and the growth, survival, and mor- BOR_HeadC=BOR_HeadD=BOR_HeadC=BOR_HeadD/HeadC phological descriptions are reported through 324 days after hatch (DAH). -

Panopea Abrupta ) Ecology and Aquaculture Production

COMPREHENSIVE LITERATURE REVIEW AND SYNOPSIS OF ISSUES RELATING TO GEODUCK ( PANOPEA ABRUPTA ) ECOLOGY AND AQUACULTURE PRODUCTION Prepared for Washington State Department of Natural Resources by Kristine Feldman, Brent Vadopalas, David Armstrong, Carolyn Friedman, Ray Hilborn, Kerry Naish, Jose Orensanz, and Juan Valero (School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington), Jennifer Ruesink (Department of Biology, University of Washington), Andrew Suhrbier, Aimee Christy, and Dan Cheney (Pacific Shellfish Institute), and Jonathan P. Davis (Baywater Inc.) February 6, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... iv LIST OF TABLES...............................................................................................................v 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................... 1 1.1 General life history ..................................................................................... 1 1.2 Predator-prey interactions........................................................................... 2 1.3 Community and ecosystem effects of geoducks......................................... 2 1.4 Spatial structure of geoduck populations.................................................... 3 1.5 Genetic-based differences at the population level ...................................... 3 1.6 Commercial geoduck hatchery practices ................................................... -

Large Spiny Lobsters Reduce the Catchability of Small Conspecifics

Vol. 666: 99–113, 2021 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published May 20 https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13695 Mar Ecol Prog Ser OPEN ACCESS Size matters: large spiny lobsters reduce the catchability of small conspecifics Emma-Jade Tuffley1,2,3,*, Simon de Lestang2, Jason How2, Tim Langlois1,3 1School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia 2Aquatic Science and Assessment, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, 39 Northside Drive, Hillarys, WA 6025, Australia 3The UWA Oceans Institute, Indian Ocean Marine Research Centre, Cnr. of Fairway and Service Road 4, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia ABSTRACT: Indices of lobster abundance and population demography are often derived from pot catch rate data and rely upon constant catchability. However, there is evidence in clawed lobsters, and some spiny lobsters, that catchability is affected by conspecifics present in pots, and that this effect is sex- and size-dependent. For the first time, this study investigated this effect in Panulirus cyg nus, an economically important spiny lobster species endemic to Western Australia. Three studies: (1) aquaria trials, (2) pot seeding experiments, and (3) field surveys, were used to investi- gate how the presence of large male and female conspecifics influence catchability in smaller, immature P. cygnus. Large P. cygnus generally reduced the catchability of small conspecifics; large males by 26−33% and large females by 14−27%. The effect of large females was complex and varied seasonally, dependent on the sex of the small lobster. Conspecific-related catchability should be a vital consideration when interpreting the results of pot-based surveys, especially if population demo graphy changes. -

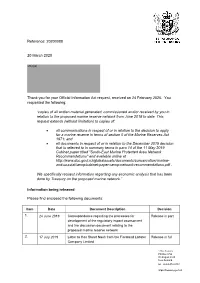

Official Information Act Response 20200088

Reference: 20200088 20 March 2020 s9(2)(a) Thank you for your Official Information Act request, received on 24 February 2020. You requested the following: “copies of all written material generated, commissioned and/or received by you in relation to the proposed marine reserve network from June 2018 to date. This request extends (without limitation) to copies of: • all communications in respect of or in relation to the decision to apply for a marine reserve in terms of section 5 of the Marine Reserves Act 1971; and • all documents in respect of or in relation to the December 2018 decision that is referred to in summary terms in para 14 of the 11 May 2019 Cabinet paper titled "South-East Marine Protected Area Network Recommendations" and available online at http://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/conservation/marine- and-coastal/semp/cabinet-paper-semp-network-recommendations.pdf . We specifically request information regarding any economic analysis that has been done by Treasury on the proposed marine network.” Information being released Please find enclosed the following documents: Item Date Document Description Decision 1. 24 June 2019 Correspondence regarding the processes for Release in part development of the regulatory impact assessment and the discussion document relating to the proposed marine reserve network 2. 17 July 2019 Letter to Hon Stuart Nash from the Fiordland Lobster Release in full Company Limited 1 The Terrace PO Box 3724 Wellington 6140 New Zealand tel. +64-4-472-2733 https://treasury.govt.nz 3. 29 July 2019 Correspondence regarding the letter to Hon Stuart Release in part Nash from the Fiordland Lobster Company Limited (Item 2) 4.