Wright Patman and the Campaigns of 1928, 1938, 1962, and 1972

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seventy-First Congress

. ~ . ··-... I . •· - SEVENTY-FIRST CONGRESS ,-- . ' -- FIRST SESSION . LXXI-2 17 , ! • t ., ~: .. ~ ). atnngr tssinnal Jtcnrd. PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE SEVENTY-FIRST CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Couzens Harris Nor beck Steiwer SENATE Dale Hastings Norris Swanson Deneen Hatfield Nye Thomas, Idaho MoNDAY, April 15, 1929 Dill Hawes Oddie Thomas, Okla. Edge Hayden Overman Townsend The first session of the Seventy-first Congress comm:enced Fess Hebert Patterson Tydings this day at the Capitol, in the city of Washington, in pursu Fletcher Heflin Pine Tyson Frazier Howell Ransdell Vandenberg ance of the proclamation of the President of the United States George Johnson Robinson, Ark. Wagner of the 7th day of March, 1929. Gillett Jones Sackett Walsh, Mass. CHARLES CURTIS, of the State of Kansas, Vice President of Glass Kean Schall Walsh, Mont. Goff Keyes Sheppard Warren the United States, called the Senate to order at 12 o'clock Waterman meridian. ~~~borough ~lenar ~p~~~~;e 1 Watson Rev. Joseph It. Sizoo, D. D., minister of the New York Ave Greene McNary Smoot nue Presbyterian Church of the city of Washington, offered the Hale Moses Steck following prayer : Mr. SCHALL. I wish to announce that my colleag-ue the senior Senator from Minnesota [Mr. SHIPSTEAD] is serio~sly ill. God of our fathers, God of the nations, our God, we bless Thee that in times of difficulties and crises when the resources Mr. WATSON. I desire to announce that my colleague the of men shrivel the resources of God are unfolded. Grant junior Senator from Indiana [Mr. RoBINSON] is unav.oidably unto Thy servants, as they stand upon the threshold of new detained at home by reason of important business. -

Officers, Officials, and Employees

CHAPTER 6 Officers, Officials, and Employees A. The Speaker § 1. Definition and Nature of Office § 2. Authority and Duties § 3. Power of Appointment § 4. Restrictions on the Speaker’s Authority § 5. The Speaker as a Member § 6. Preserving Order § 7. Ethics Investigations of the Speaker B. The Speaker Pro Tempore § 8. Definition and Nature of Office; Authorities § 9. Oath of Office §10. Term of Office §11. Designation of a Speaker Pro Tempore §12. Election of a Speaker Pro Tempore; Authorities C. Elected House Officers §13. In General §14. The Clerk §15. The Sergeant–at–Arms §16. The Chaplain §17. The Chief Administrative Officer D. Other House Officials and Capitol Employees Commentary and editing by Andrew S. Neal, J.D. and Max A. Spitzer, J.D., LL.M. 389 VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:53 Dec 04, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00389 Fmt 8875 Sfmt 8875 F:\PRECEDIT\WORKING\2019VOL02\2019VOL02.PAGETURN.V6.TXT 4473-B Ch. 6 PRECEDENTS OF THE HOUSE §18. The Parliamentarian §19. General Counsel; Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group §20. Inspector General §21. Legislative Counsel §22. Law Revision Counsel §23. House Historian §24. House Pages §25. Other Congressional Officials and Employees E. House Employees As Party Defendant or Witness §26. Current Procedures for Responding to Subpoenas §27. History of Former Procedures for Responding to Subpoenas F. House Employment and Administration §28. Employment Practices §29. Salaries and Benefits of House Officers, Officials, and Employees §30. Creating and Eliminating Offices; Reorganizations §31. Minority Party Employees 390 VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:53 Dec 04, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00390 Fmt 8875 Sfmt 8875 F:\PRECEDIT\WORKING\2019VOL02\2019VOL02.PAGETURN.V6.TXT 4473-B Officers, Officials, and Employees A. -

HOUSE. of REPRESENTATIVES-Tuesday, January 28, 1975

1610 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE January 28, 1975 would be informed by mall what benefits "Senior eitlzen.s a.re very proud;' ~~ ays. further morning business? If not~ morn would be coming. "They have worked or have been aupporte.d ing business is closed. In June. she received a letter saying that moat. of their l1vea by their working spou.s.e she was entitled to $173.40 a month. and do no~ 1in4 it. easy to a.ak for ilnanclal But the money did not come. Mrs. Menor asaist.ance. It. baa been our experience 'Ula~ 1:1 PROGRAM waited and waited, then she sent her social a prospective- appllea.nt has not received bla worker to apply !or her. check 1n due tim&. he or she Will no~ gn back Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, "And then the]' discovered. that they had down to 'the SSI omce to inquire about it." the Senate will convene tomorrew at 12 lost my whole rue and they had to start an o'clock noon. After the two leade.rs. or over again. So I"m supposed to be living on Now THE CoMPUTEa H&s CAoGHr 'UP $81.60. How do you get by on that? You ten their designees have been recogn)zed un The Social Beemity Administration. un der the standing order there will be a me. I pay $75 for my room and pay my own dertclok the Supplemental Security Income electricity. You ten me. How am I supposed period for the transaction of routine tSSif program on short notice and with in to eat?"' adequate staff last January, according to morning business of not to exceed 30 Mrs. -

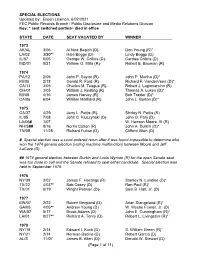

Special Election Dates

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

White House Special Files Box 43 Folder 12

Richard Nixon Presidential Library White House Special Files Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date Document Type Document Description 43 12 n.d. Report Section IV: Additional Material. Including: A. Congressional Staffs. 59 Pages Monday, May 14, 2007 Page 1 of 1 SECTION IV - ADDITIONAL MATERIAL CONGRESSIONAL STAFF by function by full committee .STANDING COMMITTEES OF tH~_§E~ATE [Democrats in romnn, Republicans in:italics] • :t.... ,...... ,:. .J .', FOREIGN AFF IRS I I I, Foreign Rclatiors ... (Sui10 422~. phono 4GG I. mcerTuesday) , J. \Y. Fulbriuht, of Arkansas. BOllrkp B. Hickenlooper, of Iowa. John J. Hparkm:m, of Alubama, Gcorq« D. Aiken, of Vermont, Mike Mnusfield, of Mon tnna, Frank! Carlson, of Kansas. \Vnyue Morse, of Oregon. John .'1. Williams, of Delaware, Albert Can', of Tennessee. Karl E. Mundt, of South Dakota, Frank .J. Lauschc, of Ohio. Cliffol!d P. Case, of Ncw Jersey, Frank Church, of Idaho. John Sherman Cooper, of Kentucky, St\l:ll't Symington, of Mis,;olll'i. I Thomas J. Dodd, of Councct.icut, i J oseph S. Clark, of Pcunsvlvania. ! Clnlbornc Pell, of l1hodo Island. 'I Eugene J. McCarthy, of Minnesota, Carl Marcy, Chief <If Staff • i ,·,.l.;Ir<l B. Ru-scll, of Georgia. .~l(l({/a,.ct Chase Smith, of :\\a'nl'. j>.,. ~kllllis, of :-'lif'sissippi. Strom Tliurnuuul, of South Carolina. :" ,.:Ift. :-'ymington, of ;\lissomi. Jack Miller, of Iowa. 111'111"\' :\1. .luckso», of Wushingto», John G. Tower, of Texas. :"'\,., :J. Ervin, Jr., of North Carolina. James B. Pearson, of Kansas. JlO\\'[lI'd \V. Cannon. of Nevada. Peter H. -

Antitrust Reform in Political Perspective.Pdf

Antitrust Reform in Political Perspective: A Constructive Critique for the Neo-Brandeisians Abstract. Today's antitrust reformers over emphasize ideological barriers to reform while failing to acknowledge significant institutional barriers arising from changes in Congress and at the Supreme Court and political barriers arising from the Democratic Party’s commitments to the knowledge economy. At the same time, reformers also fail to interrogate conservative ideology in depth, placing excess weight on the consumer welfare standard and neglecting other important aspects of the conservative argument that support the current system of lax antitrust enforcement, like a concern over regulatory capture and with the benefits of “takeover markets” for disciplining business managers. New frameworks for policy analysis should seek to confront and surmount these obstacles to develop an antitrust approach that accounts for crucial aspects of America's modern political economy. Two potential frameworks are proposed. 1. Introduction As the dimensions of America’s market power problem come into sharper focus,1 legal scholars have vigorously debated the role that lax antitrust enforcement has played in producing rising market concentration, the extent to which rising market concentration has in turn exacerbated income and wealth inequality, and how policymakers should respond. On one side of the debate stand defenders of the status quo. For these scholars, current policy, which takes a relaxed laissez-faire attitude towards large mergers and acquisitions and other anti-competitive conduct, is generally sound and deserves at best minor policy reforms.2 On the other side stand reformers like Lina Kahn—sometimes referred to as neo-Brandeisians—who have called for a substantial overhaul of the antitrust system and for new laws that will abandon many of the 1 For an overview, see JONATHAN B. -

Cannon's Precedents

CANNON’S PRECEDENTS VOLUME VII VerDate 11-MAY-2000 09:17 Apr 09, 2002 Jkt 063208 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 8686 Sfmt 8686 D:\DISC\63208.000 txed01 PsN: txed01 CANNON’S PRECEDENTS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES INCLUDING REFERENCES TO PROVISIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION, THE LAWS, AND DECISIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE By CLARENCE CANNON, A.M., LL.B., LL.D. VOLUME VII PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE ACT OF CONGRESS APPROVED MARCH 1, 1921 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1935 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 09:17 Apr 09, 2002 Jkt 063208 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 8686 Sfmt 8686 D:\DISC\63208.000 txed01 PsN: txed01 CONTENTS. VOLUME I. Chapter 1. The meeting of Congress. Chapter 2. The Clerk’s roll of the Members-elect. Chapter 3. The presiding officer at organization. Chapter 4. Procedure and powers of the Members-elect in organization. Chapter 5. The oath. Chapter 6. The officers of the House and their election. Chapter 7. Removal of officers of the House. Chapter 8. The electors and apportionment. Chapter 9. Electorates incapacitated generally. Chapter 10. Electorates distracted by Civil War. Chapter 11. Electorates in reconstruction. Chapter 12. Electorates in new States and Territories. Chapter 13. The qualifications of the Member. Chapter 14. The oath as related to qualifications. Chapter 15. Polygamy and other crimes and disqualifications. Chapter 16. Incompatible officers. Chapter 17. Times, places, and manner of election. Chapter 18. Credentials and prima facie title. Chapter 19. Irregular credentials. Chapter 20. Conflicting credentials. Chapter 21. The House the judge of contested elections. -

House of Representatives

' 334 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE ·JANUARY 18 To be senior surgeon, effective July 6, 1944 The Journal of the proceedings of yes The SPEAKER. Is there objection to Fletcher C. Stewart terday was read and approved. the request of the gentleman from Wis To be temporary passed assistant surgeon. ADJOURNMENT OVER consin? There was no objection. effective December 1, 1944 Mr. McCORMACK . Mr. Speaker, I Arthur Kornberg ask unanimous consent that . when the PERMISSION TO ADDRESS THE HOUSE To be temporary senior surgeons, effective House adjourns today it adjourn to meet Mrs. ROGERS of Massachusetts. Mr. Deeernber 1, 1944 on Monday next. Speaker, I ask unanimous consent to pro Ralph R. Braund The SPEAKER. Is there objection to ceed for 1 minute and to revise and ex Leslie McC. Smith · the request of the gentleman from Mas tend my remarks. Francis J. Weber sachusetts? The SPEAKER. Is there objection to To.be temporary surgeons, effecUve December There was no objection. the request of the gentlewoman from 1, 1944 EXTENSION OF REMARKS Massachusetts? Esta R. Allen There was no objection. William B. Hoover Mr. GRANGER. Mr. Speaker, I ask [Mrs. RoGERS of Massachusetts ad John D. Porterfield ·unanimous consent to extend my owh dressed the House. Her remarks appear Jack C. Haldeman remarks in the RECORD and to include in the Appendix.] · POSTMASTERS therein an article appearing in Collier's Mr. HALLECK . Mr. Speaker, I ask GEORGIA Weekly. The Public Printer estimates unanimous consent to address the House Grady Richardson, Donalsonville. the cost to be $130 in. excess of that for 1 minute and to revise and extend my Jesse G. -

"Clearly Vicious As a Matter of Policy": the Fight Against Federal-Aid by Richard F

"Clearly Vicious as a Matter of Policy": The Fight Against Federal-Aid By Richard F. Weingroff 2 FOREWARD The role of the Federal Government in highway building was debated from the earliest days of the Good Roads Movement in the 1880s. In 1916, 1919, and 1921, Congress developed the legislation that established and refined the Federal-aid highway program. Each time, despite pressure to take on the task of building “national highways,” Congress adopted the Federal-aid approach of providing funds to the State highway agencies as partners in project development. They would be responsible for selecting and developing projects, subject to Federal oversight. The fact that the Federal-aid concept remains at the heart of the Federal-aid highway program today does not mean support for the program has been universal or continuous. The program has been under siege many times during its history, with the attacks led by Presidents, Governors, Members of Congress, and State highway/transportation officials. This article discusses four periods during which the Federal-aid highway program was under attack: • Between the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 and the Federal Highway Act of 1921, the highway community and Federal and State officials debated whether the Federal Government should build the roads the Nation needed. • In the 1920s, the program was under pressure to downsize in favor of the States. • With the States seeking all the aid they could get in the 1930s, the issue was how much control the President should have over government expenditures for highway improvements as he attempted to revitalize and fine tune the economy. -

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party: Background and Recent

THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY Background lnformaUon for SUpportive Campaigns by Campus Groups repared by STEVE MAX Political Education ProJect, Room 309, 119 Firth Ave., N. Y .c. 10003 Associated with Students for a Democratic Society THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY: BACKGROUND AND RECENT DEVELOPMENTS by STEVE IvlAX The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was founded April 26, 1964 in order to create an opportunity for meaningful political expres sion for the 438,000 adult Negro Mississippians ~ho traditionally have been denied this right. In-addition to being a political instrument, the FDP provides a focus for the coordination of civil rights activity in the state and around the country. Although its memters do not necessarily· think in the se -terms, the MFDP is the organization above all others whose work is most directly forcing a realignment within the Democratic Party. All individuals and organizations who understand that ' when the Negro is not free, then all are in chains; who realize that the present system of discrimi nation precludes the abolition of poverty, and who have an interest in t he destruction of the Dixiecrat-Republican alliance and the purging of the racists from the Democratic Party are poteptial allies of the MFDP. BACKGROUND INFORMATION- The Mississippi Democratic Party runs the state of Mississippi _wit h an iron hand·. It controls the legislative, executive and judicial be nches of the state government. Prior to the November, 1964 elec tion all 49 state Senators and all but one of the 122 Representa tives were Democrats. Mississippi sent four Democrats and one Goldwater Republican to Congress last November. -

Wright Patman and the Impeachment of Andrew Mellon

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 23 Issue 1 Article 8 3-1985 Wright Patman and the Impeachment of Andrew Mellon Janet Schmelzer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Schmelzer, Janet (1985) "Wright Patman and the Impeachment of Andrew Mellon," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 23 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol23/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 33 WRIGHT PATMAN AND THE IMPEACHMENT OF ANDREW MELLON by Janet Schmelzer Impeachment of a public official, especially a nationally recngnized figure, has not been a common occurrence in American politics. 1 Since 1789 Congress has impeached only thirteen federal officials, and acting on only twelve cases, the Senate has voted six acquittals, two dismissals, and only four convictions. In the first impeachment from 1797 to 1799 the House of Repre sentatives charged Tennessee Senator William Blount with influencing Cherokees to aid the British against Louisiana and Spanish Florida; the Senate, which had already expelled him eighteen months before, dismissed the case for lack of jurisdiction. In 1805 in Thomas Jeffer son's administration the House charged Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase with malfeasance and misfeasance; but he was acquitted. Sixty three years later Radical Republicans, waving weak evidence and trumped-up charges, claimed that Andrew Johnson had committed "high Crimes and Misdemeanors" by violating the laws of Congress; he, too, was acquitted. -

K:\Fm Andrew\71 to 80\71.Xml

SEVENTY-FIRST CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1929, TO MARCH 3, 1931 FIRST SESSION—April 15, 1929, to November 22, 1929 SECOND SESSION—December 2, 1929, to July 3, 1930 THIRD SESSION—December 1, 1930, to March 3, 1931 SPECIAL SESSIONS OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1929, to March 5, 1929; July 7, 1930, to July 21, 1930 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—CHARLES CURTIS, of Kansas PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—GEORGE H. MOSES, of New Hampshire SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—EDWIN P. THAYER, of Indiana SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—DAVID S. BARRY, of Rhode Island SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NICHOLAS LONGWORTH, 1 of Ohio CLERK OF THE HOUSE—WILLIAM TYLER PAGE, 2 of Maryland SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH G. ROGERS, of Pennsylvania DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—BERT W. KENNEDY, of Michigan POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—FRANK W. COLLIER ALABAMA ARKANSAS Albert E. Carter, Oakland SENATORS Henry E. Barbour, Fresno SENATORS Arthur M. Free, San Jose J. Thomas Heflin, Lafayette Joseph T. Robinson, Little Rock William E. Evans, Glendale Hugo L. Black, Birmingham Thaddeus H. Caraway, Jonesboro Joe Crail, Los Angeles REPRESENTATIVES Philip D. Swing, El Centro REPRESENTATIVES William J. Driver, Osceola John McDuffie, Monroeville Pearl Peden Oldfield, 3 Batesville COLORADO Lister Hill, Montgomery Claude A. Fuller, Eureka Springs SENATORS Henry B. Steagall, Ozark Otis Wingo, 4 De Queen Lawrence C. Phipps, Denver Lamar Jeffers, Anniston Effiegene Wingo, 5 De Queen Charles W. Waterman, Denver LaFayette L. Patterson, Alexander City Heartsill Ragon, Clarksville REPRESENTATIVES William B. Oliver, Tuscaloosa D. D. Glover, Malvern William R.