Sam Rayburn and New Deal Legislation 1933-1936 Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Updated January 25, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL30857 Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Summary Each new House elects a Speaker by roll call vote when it first convenes. Customarily, the conference of each major party nominates a candidate whose name is placed in nomination. A Member normally votes for the candidate of his or her own party conference but may vote for any individual, whether nominated or not. To be elected, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of all the votes cast for individuals. This number may be less than a majority (now 218) of the full membership of the House because of vacancies, absentees, or Members answering “present.” This report provides data on elections of the Speaker in each Congress since 1913, when the House first reached its present size of 435 Members. During that period (63rd through 117th Congresses), a Speaker was elected six times with the votes of less than a majority of the full membership. If a Speaker dies or resigns during a Congress, the House immediately elects a new one. Five such elections occurred since 1913. In the earlier two cases, the House elected the new Speaker by resolution; in the more recent three, the body used the same procedure as at the outset of a Congress. If no candidate receives the requisite majority, the roll call is repeated until a Speaker is elected. Since 1913, this procedure has been necessary only in 1923, when nine ballots were required before a Speaker was elected. -

Tip O'neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003)

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 28 Issue 1 Assembled Pieces: Selected Writings by Shaun Article 14 O'Connell 11-18-2015 Tip O’Neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003) Shaun O’Connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation O’Connell, Shaun (2015) "Tip O’Neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003)," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 14. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol28/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tip O’Neill: Irish American Representative Man Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill, Man of the House as he aptly called himself in his 1987 memoir, stood as the quintessential Irish American representative man for half of the twentieth century. O’Neill, often misunderstood as a parochial, Irish Catholic party pol, was a shrewd, sensitive, and idealistic man who came to stand for a more inclusive and expansive sense of his region, his party, and his church. O’Neill’s impressive presence both embodied the clichés of the Irish American character and transcended its stereotypes by articulating a noble vision of inspired duty, determined responsibility, and joy in living. There was more to Tip O’Neill than met the eye, as several presidents learned. -

Seventy-First Congress

. ~ . ··-... I . •· - SEVENTY-FIRST CONGRESS ,-- . ' -- FIRST SESSION . LXXI-2 17 , ! • t ., ~: .. ~ ). atnngr tssinnal Jtcnrd. PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE SEVENTY-FIRST CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Couzens Harris Nor beck Steiwer SENATE Dale Hastings Norris Swanson Deneen Hatfield Nye Thomas, Idaho MoNDAY, April 15, 1929 Dill Hawes Oddie Thomas, Okla. Edge Hayden Overman Townsend The first session of the Seventy-first Congress comm:enced Fess Hebert Patterson Tydings this day at the Capitol, in the city of Washington, in pursu Fletcher Heflin Pine Tyson Frazier Howell Ransdell Vandenberg ance of the proclamation of the President of the United States George Johnson Robinson, Ark. Wagner of the 7th day of March, 1929. Gillett Jones Sackett Walsh, Mass. CHARLES CURTIS, of the State of Kansas, Vice President of Glass Kean Schall Walsh, Mont. Goff Keyes Sheppard Warren the United States, called the Senate to order at 12 o'clock Waterman meridian. ~~~borough ~lenar ~p~~~~;e 1 Watson Rev. Joseph It. Sizoo, D. D., minister of the New York Ave Greene McNary Smoot nue Presbyterian Church of the city of Washington, offered the Hale Moses Steck following prayer : Mr. SCHALL. I wish to announce that my colleag-ue the senior Senator from Minnesota [Mr. SHIPSTEAD] is serio~sly ill. God of our fathers, God of the nations, our God, we bless Thee that in times of difficulties and crises when the resources Mr. WATSON. I desire to announce that my colleague the of men shrivel the resources of God are unfolded. Grant junior Senator from Indiana [Mr. RoBINSON] is unav.oidably unto Thy servants, as they stand upon the threshold of new detained at home by reason of important business. -

NANCY BECK YOUNG, Ph.D. Department of History University of Houston 524 Agnes Arnold Hall Houston, Texas 77204-3003 713.743.4381 [email protected]

NANCY BECK YOUNG, Ph.D. Department of History University of Houston 524 Agnes Arnold Hall Houston, Texas 77204-3003 713.743.4381 [email protected] EDUCATIONAL PREPARATION The University of Texas at Austin, Ph.D., History, May 1995 The University of Texas at Austin, M.A., History, December 1989 Baylor University, B.A., History, May 1986 ACADEMIC POSITIONS July 2012-present, University of Houston, Department Chair and Professor August 2007-present, University of Houston, Professor August 2001-May 2007, McKendree College, Associate Professor August 1997-August 2001, McKendree College, Assistant Professor June 1997-August 1997, The University of Texas at Austin, Lecturer August 1995-May 1996, Southwest Missouri State University, Lecturer RESIDENTIAL FELLOWSHIPS September 2003-May 2004, Fellow, Woodrow Wilson International Center, Washington, D.C. August 1996-May 1997, Clements Fellow in Southwest Studies, Southern Methodist University AWARDS AND HONORS 2002, D.B. Hardeman Prize for the Best Book on Congress 2002, Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Illinois Professor of the Year 2001, William Norman Grandy Faculty Award, McKendree College 1996, Ima Hogg Historical Achievement Award for Outstanding Research on Texas History, Winedale Historical Center Advisory Council, Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin PUBLICATIONS MONOGRAPHS “Landslide Lyndon? The 1964 Presidential Election and the Realignment of American Political Values,” under advance contract to the University Press of Kansas with tentative submission date of fall 2016. “100 Days that Changed America: FDR, Congress, and the New Deal,” under advance contract and review at Oxford University Press. Why We Fight: Congress and the Politics of World War II (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013). -

DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North

4Z SAM RAYBURN: TRIALS OF A PARTY MAN DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Edward 0. Daniel, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1979 Daniel, Edward 0., Sam Rayburn: Trials of a Party Man. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1979, 330 pp., bibliog- raphy, 163 titles. Sam Rayburn' s remarkable legislative career is exten- sively documented, but no one has endeavored to write a political biography in which his philosophy, his personal convictions, and the forces which motivated him are analyzed. The object of this dissertation is to fill that void by tracing the course of events which led Sam Rayburn to the Speakership of the United States House of Representatives. For twenty-seven long years of congressional service, Sam Rayburn patiently, but persistently, laid the groundwork for his elevation to the speakership. Most of his accomplish- ments, recorded in this paper, were a means to that end. His legislative achievements for the New Deal were monu- mental, particularly in the areas of securities regulation, progressive labor laws, and military preparedness. Rayburn rose to the speakership, however, not because he was a policy maker, but because he was a policy expeditor. He took his orders from those who had the power to enhance his own station in life. Prior to the presidential election of 1932, the center of Sam Rayburn's universe was an old friend and accomplished political maneuverer, John Nance Garner. It was through Garner that Rayburn first perceived the significance of the "you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours" style of politics. -

Nancy Pelosi Is the 52Nd Speaker of the House of Representatives, Having Made History in 2007 When She Was Elected the First Woman to Serve As Speaker of the House

More than 30 Years of Leadership & Progress SPEAKER.GOV “Pelosi is one of the most consequential political figures of her generation. It was her creativity, stamina and willpower that drove the defining Democratic accomplishments of the past decade, from universal access to health coverage to saving the U.S. economy from collapse, from reforming Wall Street to allowing gay people to serve openly in the military. Her Republican successors’ ineptitude has thrown her skills into sharp relief. It’s not a stretch to say Pelosi is one of very few legislators in Washington who actually know what they’re doing.” – TIME Magazine Cover Profile, September 2018 Nancy Pelosi is the 52nd Speaker of the House of Representatives, having made history in 2007 when she was elected the first woman to serve as Speaker of the House. Now in her third term as Speaker, Pelosi made history again in January 2019 when she regained her position second-in-line to the presidency, the first person to do so in more than 60 years. As Speaker, Pelosi is fighting For The People, working to lower health care costs, increase workers’ pay through strong economic growth and rebuilding America, and clean up corruption for make Washington work for all. For 31 years, Speaker Pelosi has represented San Francisco, California’s 12th District, in Congress. She has led House Democrats for 16 years and previously served as House Democratic Whip. In 2013, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame at a ceremony in Seneca Falls, the birthplace of the American women’s rights movement. -

The Political Speaking of Oscar Branch Colquitt, 1906-1913

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 The olitP ical Speaking of Oscar Branch Colquitt, 1906-1913. Dencil R. Taylor Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Taylor, Dencil R., "The oP litical Speaking of Oscar Branch Colquitt, 1906-1913." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3354. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3354 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Officers, Officials, and Employees

CHAPTER 6 Officers, Officials, and Employees A. The Speaker § 1. Definition and Nature of Office § 2. Authority and Duties § 3. Power of Appointment § 4. Restrictions on the Speaker’s Authority § 5. The Speaker as a Member § 6. Preserving Order § 7. Ethics Investigations of the Speaker B. The Speaker Pro Tempore § 8. Definition and Nature of Office; Authorities § 9. Oath of Office §10. Term of Office §11. Designation of a Speaker Pro Tempore §12. Election of a Speaker Pro Tempore; Authorities C. Elected House Officers §13. In General §14. The Clerk §15. The Sergeant–at–Arms §16. The Chaplain §17. The Chief Administrative Officer D. Other House Officials and Capitol Employees Commentary and editing by Andrew S. Neal, J.D. and Max A. Spitzer, J.D., LL.M. 389 VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:53 Dec 04, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00389 Fmt 8875 Sfmt 8875 F:\PRECEDIT\WORKING\2019VOL02\2019VOL02.PAGETURN.V6.TXT 4473-B Ch. 6 PRECEDENTS OF THE HOUSE §18. The Parliamentarian §19. General Counsel; Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group §20. Inspector General §21. Legislative Counsel §22. Law Revision Counsel §23. House Historian §24. House Pages §25. Other Congressional Officials and Employees E. House Employees As Party Defendant or Witness §26. Current Procedures for Responding to Subpoenas §27. History of Former Procedures for Responding to Subpoenas F. House Employment and Administration §28. Employment Practices §29. Salaries and Benefits of House Officers, Officials, and Employees §30. Creating and Eliminating Offices; Reorganizations §31. Minority Party Employees 390 VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:53 Dec 04, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00390 Fmt 8875 Sfmt 8875 F:\PRECEDIT\WORKING\2019VOL02\2019VOL02.PAGETURN.V6.TXT 4473-B Officers, Officials, and Employees A. -

Luncheon Friday Closes Journalism Workshop

V-IBRART n is copxss The Battalion Volume 69 COLLEGE STATION, TEXAS THURSDAY, JULY 28, 1960 Number 12$ Luncheon Friday Closes Journalism Workshop Parking Rules Barbecue Planned Deadline Set Tonight for 300 Get Revisions For Ordering More than 300 high school newspaper and yearbook staff members and sponsors will end their week-long stay here Friday at noon when Frank King, executive editor of The The new parking plan for faculty and staff members SeasonDucats Houston Post, will give the closing talk at the awards lunch which went into effect during the spring semester of the eon in Sbisa Dining Hall. 1959-60 school year will be discontinued and a modified plan Sunday at midnight is the dead The high school students and teachers have been here will be used, according to Dean of Students James P. Hanni- line for ordering priority tickets since Sunday afternoon for the second annual High School gan. for the three home football Publications Workshop, sponsored by the Department of For the 1960-61 school year the serious defects in that the number games this fall, according to Pat Journalism. College Executive Committee has of visitor spaces was too limited, Dial, business manager for the A barbecue, to be followed by dancing and entertainment, approved the modified parking sys a large number of reserved spaces Department of Athletics. south of G. Rollie White Coliseum tonight beginning at 6 will tem wherein the zone administra were frequently empty and mark be the final entertainment phase of the workshop. Friday The season books, good for the tors will make available a reason ing and painting was too costly, Texas Tech, Sept. -

HOUSE. of REPRESENTATIVES-Tuesday, January 28, 1975

1610 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE January 28, 1975 would be informed by mall what benefits "Senior eitlzen.s a.re very proud;' ~~ ays. further morning business? If not~ morn would be coming. "They have worked or have been aupporte.d ing business is closed. In June. she received a letter saying that moat. of their l1vea by their working spou.s.e she was entitled to $173.40 a month. and do no~ 1in4 it. easy to a.ak for ilnanclal But the money did not come. Mrs. Menor asaist.ance. It. baa been our experience 'Ula~ 1:1 PROGRAM waited and waited, then she sent her social a prospective- appllea.nt has not received bla worker to apply !or her. check 1n due tim&. he or she Will no~ gn back Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, "And then the]' discovered. that they had down to 'the SSI omce to inquire about it." the Senate will convene tomorrew at 12 lost my whole rue and they had to start an o'clock noon. After the two leade.rs. or over again. So I"m supposed to be living on Now THE CoMPUTEa H&s CAoGHr 'UP $81.60. How do you get by on that? You ten their designees have been recogn)zed un The Social Beemity Administration. un der the standing order there will be a me. I pay $75 for my room and pay my own dertclok the Supplemental Security Income electricity. You ten me. How am I supposed period for the transaction of routine tSSif program on short notice and with in to eat?"' adequate staff last January, according to morning business of not to exceed 30 Mrs. -

Special Election Dates

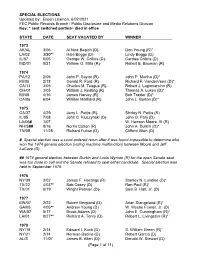

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

The Sam Rayburn Papers: a Preliminary Investigation by DEWARD G

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/35/3-4/331/2745739/aarc_35_3-4_x71222th62218485.pdf by guest on 03 October 2021 The Sam Rayburn Papers: A Preliminary Investigation By DEWARD G. BROWN PEAKER OF THE HOUSE Sam Rayburn died on November 16, 1961, ending a long and distinguished political career. S Rayburn became Speaker in 1940 and served in that position for seventeen years, longer than any other man in history. He was particularly influential in the Democratic Party and acted as Chair- man of the Democratic National Convention in 1948, 1952, and 1956. He represented his district well for over two generations and, along with Senator Lyndon Johnson, gave Texas a strong voice in national affairs. Former President Johnson is remembered in Texas by his Presidential Library in the capital city of Austin, but Rayburn is remembered by a small, privately funded library in Bonham, his home town, in tranquil, rural northeast Texas. These libraries symbolize the public life of the two men: Rayburn, with a quiet and humble political style, preferred a career in the House, whereas Johnson, with a more energetic style, rose to the Presidency. After serving as Speaker for a few years, Rayburn wanted to build a small, unpretentious library in his hometown. He hoped to make it both a permanent depository for his official and personal papers and a center for the study of congressional history and affairs. In 1948, using the Collier Award of $10,000 he received for distin- guished service in Congress, the Speaker started a library fundraising campaign which brought contributions ranging from school chil- dren's pennies to sums of $50,000 donated by friends and admirers.