Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Updated January 25, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL30857 Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Summary Each new House elects a Speaker by roll call vote when it first convenes. Customarily, the conference of each major party nominates a candidate whose name is placed in nomination. A Member normally votes for the candidate of his or her own party conference but may vote for any individual, whether nominated or not. To be elected, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of all the votes cast for individuals. This number may be less than a majority (now 218) of the full membership of the House because of vacancies, absentees, or Members answering “present.” This report provides data on elections of the Speaker in each Congress since 1913, when the House first reached its present size of 435 Members. During that period (63rd through 117th Congresses), a Speaker was elected six times with the votes of less than a majority of the full membership. If a Speaker dies or resigns during a Congress, the House immediately elects a new one. Five such elections occurred since 1913. In the earlier two cases, the House elected the new Speaker by resolution; in the more recent three, the body used the same procedure as at the outset of a Congress. If no candidate receives the requisite majority, the roll call is repeated until a Speaker is elected. Since 1913, this procedure has been necessary only in 1923, when nine ballots were required before a Speaker was elected. -

19301 Winter 04 News

WINTER 2011 BBlueCrossBBlueCrosslluueeCCrroossss BBlueShieldBBlueShieldlluueeSShhiieelldd ofooofff Tennessee:TTTennessee:eennnneesssseeee:: TTiTTiiittlettlellee SponsorSSSponsorppoonnssoorr oofoofff tthetthehhee StateSSStatettaattee BasketballBBasketballBaasskkeettbbaallll ChampionshipsCChampionshipsChhaammppiioonnsshhiippss • A.F. BRIDGES AWARDS PROGRAM WINNERS • DISTINGUISHED SERVICE RECOGNITION • 2011 BASKETBALL CHAMPIONSHIP SCHEDULES TENNESSEE SECONDARY SCHOOL ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION HERMITAGE, TENNESSEE TSSAA NEWS ROUTING REPORT 2010 FALL STATE CHAMPIONS TSSAA is proud to recognize the 2010 Fall Sports Champions This routing report is provided to assist principals and athletic directors in ensuring that the TSSAA News is seen by all necessary CHEERLEADING CROSS-COUNTRY GOLF school personnel. CHEER & DANCE A-AA GIRLS Each individual should check the appropriate A-AA GIRLS Signal Mountain High School box after having read the News and pass it on Small Varsity Jazz Greeneville High School to the next individual on the list or return it to Brentwood High School AAA GIRLS the athletic administrator. AAA GIRLS Soddy-Daisy High School K Large Varsity Jazz Oak Ridge High School K Athletic Director Ravenwood High School DIVISION II-A GIRLS Girls Tennis Coach K DIVISION II-A GIRLS Franklin Road Academy Baseball Coach K Junior Varsity Pom Webb School of Knoxville Boys Tennis Coach K DIVISION II-AA GIRLS Girls Basketball Coach Arlington High School K DIVISION II-AA GIRLS Baylor School K Girls Track & Field Coach Small Varsity Pom Baylor School K Boys Basketball Coach Briarcrest Christian School A-AA BOYS K Boys Track & Field Coach A-AA BOYS Christian Academy of Knoxville K Girls Cross Country Coach Large Varsity Pom K Girls Volleyball Coach Martin Luther King High School K Boys Cross Country Coach Arlington High School AAA BOYS K Wrestling Coach AAA BOYS Hendersonville High School K Football Coach Junior Varsity Hip Hop Hardin Valley Academy K Cheerleading Coach St. -

Tip O'neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003)

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 28 Issue 1 Assembled Pieces: Selected Writings by Shaun Article 14 O'Connell 11-18-2015 Tip O’Neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003) Shaun O’Connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation O’Connell, Shaun (2015) "Tip O’Neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003)," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 14. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol28/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tip O’Neill: Irish American Representative Man Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill, Man of the House as he aptly called himself in his 1987 memoir, stood as the quintessential Irish American representative man for half of the twentieth century. O’Neill, often misunderstood as a parochial, Irish Catholic party pol, was a shrewd, sensitive, and idealistic man who came to stand for a more inclusive and expansive sense of his region, his party, and his church. O’Neill’s impressive presence both embodied the clichés of the Irish American character and transcended its stereotypes by articulating a noble vision of inspired duty, determined responsibility, and joy in living. There was more to Tip O’Neill than met the eye, as several presidents learned. -

CRS Report for Congress Received Through the CRS Web

Order Code RL30665 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web The Role of the House Majority Leader: An Overview Updated April 4, 2006 Walter J. Oleszek Senior Specialist in the Legislative Process Government and Finance Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress The Role of the House Majority Leader: An Overview Summary The majority leader in the contemporary House is second-in-command behind the Speaker of the majority party. Typically, the majority leader functions as the Speaker’s chief lieutenant or “field commander” for day-to-day management of the floor. Although the majority leader’s duties are not especially well-defined, they have evolved to the point where it is possible to spotlight two fundamental and often interlocking responsibilities that orient the majority leader’s work: institutional and party. From an institutional perspective, the majority leader has a number of duties. Scheduling floor business is a prime responsibility of the majority leader. Although scheduling the House’s business is a collective activity of the majority party, the majority leader has a large say in shaping the chamber’s overall agenda and in determining when, whether, how, or in what order legislation is taken up. In addition, the majority leader is active in constructing winning coalitions for the party’s legislative priorities; acting as a public spokesman — defending and explaining the party’s program and agenda; serving as an emissary to the White House, especially when the President is of the same party; and facilitating the orderly conduct of the House’s business. From a party perspective, three key activities undergird the majority leader’s principal goal of trying to ensure that the party remains in control of the House. -

House Officer, Party Leader, and Representative Name Redacted Specialist on Congress and the Legislative Process

The Speaker of the House: House Officer, Party Leader, and Representative name redacted Specialist on Congress and the Legislative Process November 12, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov 97-780 The Speaker of the House: House Officer, Party Leader, and Representative Summary The Speaker of the House of Representatives is widely viewed as symbolizing the power and authority of the House. The Speaker’s most prominent role is that of presiding officer of the House. In this capacity, the Speaker is empowered by House rules to administer proceedings on the House floor, including recognition of Members to speak on the floor or make motions and appointment of Members to conference committees. The Speaker also oversees much of the non- legislative business of the House, such as general control over the Hall of the House and the House side of the Capitol and service as chair of the House Office Building Commission. The Speaker’s role as “elect of the elect” in the House also places him or her in a highly visible position with the public. The Speaker also serves as not only titular leader of the House but also leader of the majority party conference. The Speaker is often responsible for airing and defending the majority party’s legislative agenda in the House. The Speaker’s third distinct role is that of an elected Member of the House. Although elected as an officer of the House, the Speaker continues to be a Member as well. As such the Speaker enjoys the same rights, responsibilities, and privileges of all Representatives. -

Seventy-First Congress

. ~ . ··-... I . •· - SEVENTY-FIRST CONGRESS ,-- . ' -- FIRST SESSION . LXXI-2 17 , ! • t ., ~: .. ~ ). atnngr tssinnal Jtcnrd. PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE SEVENTY-FIRST CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Couzens Harris Nor beck Steiwer SENATE Dale Hastings Norris Swanson Deneen Hatfield Nye Thomas, Idaho MoNDAY, April 15, 1929 Dill Hawes Oddie Thomas, Okla. Edge Hayden Overman Townsend The first session of the Seventy-first Congress comm:enced Fess Hebert Patterson Tydings this day at the Capitol, in the city of Washington, in pursu Fletcher Heflin Pine Tyson Frazier Howell Ransdell Vandenberg ance of the proclamation of the President of the United States George Johnson Robinson, Ark. Wagner of the 7th day of March, 1929. Gillett Jones Sackett Walsh, Mass. CHARLES CURTIS, of the State of Kansas, Vice President of Glass Kean Schall Walsh, Mont. Goff Keyes Sheppard Warren the United States, called the Senate to order at 12 o'clock Waterman meridian. ~~~borough ~lenar ~p~~~~;e 1 Watson Rev. Joseph It. Sizoo, D. D., minister of the New York Ave Greene McNary Smoot nue Presbyterian Church of the city of Washington, offered the Hale Moses Steck following prayer : Mr. SCHALL. I wish to announce that my colleag-ue the senior Senator from Minnesota [Mr. SHIPSTEAD] is serio~sly ill. God of our fathers, God of the nations, our God, we bless Thee that in times of difficulties and crises when the resources Mr. WATSON. I desire to announce that my colleague the of men shrivel the resources of God are unfolded. Grant junior Senator from Indiana [Mr. RoBINSON] is unav.oidably unto Thy servants, as they stand upon the threshold of new detained at home by reason of important business. -

K:\Fm Andrew\61 to 70\70.Xml

SEVENTIETH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1927, TO MARCH 3, 1929 FIRST SESSION—December 5, 1927, to May 29, 1928 SECOND SESSION—December 3, 1928, to March 3, 1929 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—CHARLES G. DAWES, of Illinois PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—GEORGE H. MOSES, 1 of New Hampshire SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—EDWIN P. THAYER, 2 of Indiana SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—DAVID S. BARRY, of Rhode Island SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NICHOLAS LONGWORTH, 3 of Ohio CLERK OF THE HOUSE—WILLIAM TYLER PAGE, 4 of Maryland SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH G. ROGERS, of Pennsylvania DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—BERT W. KENNEDY, of Michigan POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—FRANK W. COLLIER ALABAMA Thaddeus H. Caraway, Jonesboro COLORADO REPRESENTATIVES SENATORS SENATORS J. Thomas Heflin, Lafayette William J. Driver, Osceola Lawrence C. Phipps, Denver 7 Hugo L. Black, Birmingham William A. Oldfield, Batesville Charles W. Waterman, Denver REPRESENTATIVES Pearl Peden Oldfield, 8 Batesville John McDuffie, Monroeville John N. Tillman, Fayetteville REPRESENTATIVES Lister Hill, Montgomery Otis Wingo, De Queen William N. Vaile, 9 Denver Henry B. Steagall, Ozark Heartsill Ragon, Clarksville S. Harrison White, 10 Denver Lamar Jeffers, Anniston James B. Reed, Lonoke Charles B. Timberlake, Sterling William B. Bowling, 5 Lafayette Tilman B. Parks, Camden Guy U. Hardy, Canon City LaFayette L. Patterson, 6 Alexander Edward T. Taylor, Glenwood Springs City CALIFORNIA William B. Oliver, Tuscaloosa SENATORS CONNECTICUT Miles C. Allgood, Allgood Edward B. Almon, Tuscumbia Hiram W. Johnson, San Francisco SENATORS George Huddleston, Birmingham Samuel M. Shortridge, Menlo Park George P. -

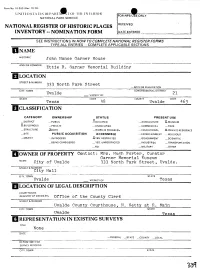

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form Date Entered

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) ^jt UNHLDSTAn.S DLPARTP^K'T Oh TUt, INILR1OR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC John Nance Garner House AND/OR COMMON Ettie R. Garner Memorial Buildinp [LOCATION STREET& NUMBFR 333 North Park Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT CITY. TOWN 21 Uvalde VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Texas Uvalde 463 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT ^.PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL __PARK —STRUCTURE J&BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER. OWNER OF PROPERTY Contact: Mrs. Hugh Porter, Curator Garner Memorial Museum NAME City of Uvalde 333 North Park Street, Uvalde STREETS NUMBER City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Uvalde VICINITY OF Texas [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC office of the County Clerk STREETS NUMBER Uvalde County Courthouse, N. Getty at E. Main CITY, TOWN STATE Uvalde Texas REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE ^LcOOD —RUINS ?_ALTERED _MOVED DATE——————— _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE From 1920 until his wife's death in 1952, Garner made his permanent home in this two-story, H-shaped, hip-roofed, brick house, which was designed for him by architect Atlee Ayers. -

2. Krehbiel and Wiseman

Joe Cannon and the Minority Party 479 KEITH KREHBIEL Stanford University ALAN E. WISEMAN The Ohio State University Joe Cannon and the Minority Party: Tyranny or Bipartisanship? The minority party is rarely featured in empirical research on parties in legis- latures, and recent theories of parties in legislatures are rarely neutral and balanced in their treatment of the minority and majority parties. This article makes a case for redressing this imbalance. We identified four characteristics of bipartisanship and evaluated their descriptive merits in a purposely hostile testing ground: during the rise and fall of Speaker Joseph G. Cannon, “the Tyrant from Illinois.” Drawing on century- old recently discovered records now available in the National Archives, we found that Cannon was anything but a majority-party tyrant during the important committee- assignment phase of legislative organization. Our findings underscore the need for future, more explicitly theoretical research on parties-in-legislatures. The minority party is the crazy uncle of American politics, showing up at most major events, semiregularly causing a ruckus, yet stead- fastly failing to command attention and reflection. In light of the large quantity of new research on political parties, the academic marginalization of the minority party is ironic and unfortunate. It appears we have an abundance of theoretical and empirical arguments about parties in legislatures, but the reality is that we have only slightly more than half of that. The preponderance of our theories are about a single, strong party in the legislature: the majority party. A rare exception to the majority-centric rule is the work of Charles Jones, who, decades ago, lamented that “few scholars have made an effort to define these differences [between majority and minority parties] in any but the most superficial manner” (1970, 3). -

New York's Political Resurgence

April 8, 2015 New York’s political resurgence by JOSHUA SPIVAK New York, once a center of America's political world, long ago fell on hard times. Where the state was once practically guaranteed a slot on at least one of the presidential tickets, it has been many years since a New Yorker was a real contender for the presidency. And the record in Congress has been even worse — there the state always underperformed. But that may all be changing in a hurry. Former Senator Hillary Clinton (D-N.Y.) is the overwhelming favorite for the Democratic presidential nomination and now, thanks to the retirement of Sen. Harry Reid, (D-Nev.), Sen. Chuck Schumer (N.Y.) is the likely next Democratic Leader in the Senate. For the first time in decades, the Empire State may be a state on the political rise. Schumer’s ascension may be the biggest break with history. For the better part of a century, New York was the presidential incubator. But the state has never been particularly successful in Congress. No New Yorker has ever served as Senate Majority or Minority Leader. It had one Minority Whip — the first one ever, back in 1915. Since then, no other New Yorker has served in the top two positions in the upper chamber. New Yorkers haven’t exactly grabbed the reigns in the House either — the state has only elected two Speakers of the House — the last one, Theodore Pomeroy, left office in 1869. Even the lower leadership positions have been bereft of New Yorkers. The state has provided one House Majority Leader — the very first one, Sereno Payne. -

Chapter CLII.1 the OATH

Chapter CLII.1 THE OATH. 1. Administration to the Speaker. Sections 6, 7. 2. Limited jurisdiction of the Speaker in administering. Section 8. 3. Challenging the right of a Member to be sworn. Sections 9–11. 4. Administration before arrival of credentials. Sections 12, 13. 5. Administration to Members away from House. Sections 14–19. 6. Administration by Speaker pro tempore. Section 20. 7. Relations to the quorum, reading of the Journal and Calendar Wednesday. Sec- tions 21, 22. 6. While the oath has usually been administered to the Speaker by the Member of longest consecutive service, that practice is not always fol- lowed.—On May 19, 1919,2 the oath of office was administered to Speaker Fred- erick H. Gillett, himself the ‘‘Father of the House,’’ by Mr. Joseph G. Cannon, of Illinois, who, though the Member of longest service, was one of the younger Mem- bers of the House in consecutive service. 7. On April 4, 1911,3 Mr. J. Fred C. Talbott, of Maryland, one of the older Members of the House, but not the oldest in consecutive service, administered the oath to Mr. Speaker Clark. 8. Previously it was the custom to administer the oath by State delega- tions, but beginning with the Seventy-first Congress Members elect have been sworn in en masse.—On April 15, 1929,4 following the administration of the oath of office to the Speaker elect, the Speaker 5 after addressing the House announced: The Chair asks the attention of all the Members of the House for a moment. The Chair has decided to practice an innovation in the manner of administering the oath of office to Members. -

Nicholas Longworth 17 Nicholas Longworth: Art Patron of Cincinnati

Spring 1988 Nicholas Longworth 17 Nicholas Longworth: Art Patron of Cincinnati Abby S. Schwartz ... A little bit of an ugly man came in...he came forward and, taking my hand and squeezing it hard, he looked at me with a keen, earnest gaze. ... His manners are extremely rough and almost course, but his shrewd eyes and plain manner hide a very strong mind and generous heart.1 These observations made in 1841 by the young artist Lilly Martin Spencer hardly seem appropriate for a man who was among America's wealthiest and one of Cin- cinnati's most prominent citizens. Described by another contemporary as "dry and caustic in his remarks" and "plain and careless in his dress, looking more like a beggar than a millionaire,"2 Nicholas Longworth, however eccentric and controversial, was a leading Cincinnati art patron as well as an outstanding collector and a generous supporter of the arts during the middle of the nineteenth century. Longworth's eccentricities of dress and behav- ior are well documented in photographs, portraits, and anec- dotes. While the Portrait of Nicholas Longworth by Robert Scott Duncanson (1 821-1872) portrays the subject as an important property owner and vintner, the work also docu- ments Longworth's eccentric habit of pinning notes to his suit cuffs to remind himself of important errands and appoint- ments. The portrait, painted in 18 5 8, is on permanent loan to the Cincinnati Art Museum from the Ohio College of Applied Science. An often repeated anecdote details young Abraham Lincoln's visit to Longworth's renowned gardens During the years he resided at Belmont (now where Lincoln mistook the master of the house for a gardener: the Taft Museum), 1830 until his death in 18 6 3, Longworth In the middle of the gravel path leading to a pillared portico, a amassed a personal art collection, assisted a number of artists small, queerly dressed old man, with no appearance whatever offinancially, offered advice and letters of introduction to having outgrown his old-fashioned raiment, was weeding.