Mapping Debris Fields of Lost US Ships from the 1944 Battle of Leyte Gulf Midshipman 1/C Buinauskas, USN, Class of 2020; Advisor: Professor Peter L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Over 65 Percent Voter Turnout in General Election

WEDNESDAY, NOV. 7, 2018 ■ VOLUME 3, NUMBER 05 ■ 12 PAGES ■ PRICE 75¢ www.MariesCountyAdvocate.com We salute our veterans • Happy Veterans Day • 1918-2018 Over 65 percent voter turnout in General Election Stratman elected to Presiding Commissioner, voters send Hawley to US Senate Clean Mo, medical Marijuana, bingo passes, minimum wages increases, gas tax falls short Maries County voters leaned decidedly Republican was not as high as she was thinking it would be when The campaigning process was a positive experience for to 84 votes. in Tuesday’s General Election, favoring all right-wing she saw the long lines at the precincts, but the nearly 66 him as the people were all very nice. Maries County vote totals for the amendments and candidates by a large margin, including choosing Victor percent voter turnout surpassed her previous prediction “I am looking forward to getting started,” he said, propositions: Amendment 1 “Clean Missouri” was Stratman as the next Maries County Presiding Com- of 58 percent. adding he plans to begin attending the county commis- defeated here with 2,038 to 1,800 votes; Amendment 2 missioner. In the presiding commissioner race, Republican Victor sion meetings to learn all he can. medical marijuana won in the county with 1,982 to 1,914 County residents also voted against the two local tax Stratman netted 2,893 votes (73.13 percent) and Demo- The city of Vienna public safety sales tax question was votes; Amendment 3 medical marijuana lost in the county increases and the statewide gasoline tax hike proposal. crat Vernon (Sonny) Helton received 998 votes (24.92 a close vote but ultimately failed with 104 to 94 votes. -

Print All Readings (Pdf)

Breaking News English.com Ocean explorers film world's deepest shipwreck – 6th April, 2021 Level 0 Ocean explorers filmed the deepest known shipwreck for the first time. The Japanese Navy sunk the World War II battleship in 1944. It is now on the ocean floor, 6,456 metres deep. The film crew went down to that depth in a special submarine that can work in the deep-sea pressure. The filming happened in two eight-hour dives. The lead explorer was in the US Navy. He is an adventurer. He is the first person ever to get to the top of all the world's continents, both poles, and the bottom of all the world's oceans. He said: "As a US Navy officer, I'm proud to have helped bring clarity and closure to the [battleship]." Level 1 Ocean explorers filmed the world's deepest known shipwreck for the first time. The World War II battleship, the USS Johnston, was sunk by the Japanese Navy in 1944. The shipwreck is now on the ocean floor, around 6,456 metres deep. The film crew went down to that incredible depth and darkness in a submersible that can deal with the pressure of the deep ocean. The filming took place during two eight-hour dives. The lead explorer, Victor Vescovo, was in the US Navy and is an adventurer. He has visited hard-to-get- to places. He is the first person ever to get to the top of all the world's continents, both poles, and the bottom of all the world's oceans. -

Uss Lexington Found After She Was Sunk in the Battle of Coral Sea

BARTREAD USS LEXINGTON FOUND AFTER SHE WAS SUNK IN THE BATTLE OF CORAL SEA On the 4th May 2018 we celebrate the 76th anniversary of the Battle of the Coral Sea in World War II. In this special “Bartread” edition we re- member the bitterly fought battle off the coast of Australia. Special Coral Sea Annive rsary Issue 29 2018 WARTIME VEHICLE CONSERVATION GROUP OFFICE BEARERS 2017 — 2018 PRESIDENT: Kevin TIPLER 0403 267 294 [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT: Tony COLE 0437 793 560 [email protected] SECRETARY: Rick SHEARMAN 0408 835 018 [email protected] TREASURER: Mick JENNER 0408817 485 [email protected] 0883982738 NEWSLETTER EDITOR: Tony VAN RHODA 0409 833 879 [email protected] 0885362627 WEBSITE OFFICER: Mick JENNER 0408 817 485 [email protected] 0889382738 HISTORIC REGISTER: Mick JENNER VEHICLE INSPECTORS: Rick SHEARMAN Mick JENNER John JENNER PUBLIC OFFICER: Mick JENNER FEDERATION DELEGATE Hugh DAVIS P/2. WVCG Office Bearers P/8. P/3. USS Lexington found 2 miles P/18. Items For Sale down in the Coral Sea P/20. WVCG Special Events P/7. P/20. 2 USS Lexington: The WWII aircraft carrier was found 76 years after it sank in the Battle of the Coral Sea The USS Lexington was found 3km (2 miles) underwater in the Coral Sea, about 800km off Australia's east coast. The ship was lost in the Battle of the Coral Sea, fought with Japan from 4-8 May 1942. More than 200 crew members died in the fighting. The US Navy con- firmed the ship had been discovered by a search team led by Microsoft co-founder Paul Al- len. -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

HOUSING and LAND USE REGULATORY BOARD Lupong Nangangasiwa Sa Pabahay at Gamit Ng Lupa

Republic of the Philippines Office of the President HOUSING AND LAND USE REGULATORY BOARD Lupong Nangangasiwa sa Pabahay at Gamit ng Lupa HLURB MEMORANDUM CIRCULAR NO. 03 Series of 2019 ( AP¥'\ L OS) 2019) TO HLURB CENTRAL VISAYAS REGION FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER SUBJECT INTEGRATION OF SAN PEDRO BAY AND LEYTE GULF (SPBLGB) FRAMEWORK PLAN IN THE COMPREHENSIVE LAND USE PLANS OF AFFECTED LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNITS The Regional Land Use Committee (RLUC) Region VIII adopted the San Pedro Bay and Leyte Gulf Basin (SPBLGB) Framework Plan through RLUC Resolution No. 08 Series of 2018. The framework plan provided for the strategic and policy framework for the sustainable and resilient development path of the SPBLGB area. The framework plan also provided guidance to decision-makers, planners and other stakeholders especially in the implementation of the adopted spatial structure and land and water use prescriptions for the SPBLGB. To further supplement the results or outcomes of Climate and Disaster Risk Assessment (CDRA) process, the policies, spatial framework, programs and projects outlined in the SPBLGB Framework Plan that also aims to improve the adaptive capacities of communities and local government units along the coastlines of San Pedro Bay and Leyte Gulf Basin, shall be considered or incorporated in the preparation or updating of Comprehensive Land Use Plans of the identified local government units. Local government units covered by the framework plan includes Tacloban City, municipalities of Palo, Tanauan, Dulag, Tolosa, Mayorga, MacArthur and Abuyog in the Province of Leyte; Municipalities of Basey and Marabut in the Province of Samar; and Municipalities of Lawaan and Balangiga in the Province of Eastern Samar. -

World War II at Sea This Page Intentionally Left Blank World War II at Sea

World War II at Sea This page intentionally left blank World War II at Sea AN ENCYCLOPEDIA Volume I: A–K Dr. Spencer C. Tucker Editor Dr. Paul G. Pierpaoli Jr. Associate Editor Dr. Eric W. Osborne Assistant Editor Vincent P. O’Hara Assistant Editor Copyright 2012 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World War II at sea : an encyclopedia / Spencer C. Tucker. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59884-457-3 (hardcopy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-59884-458-0 (ebook) 1. World War, 1939–1945—Naval operations— Encyclopedias. I. Tucker, Spencer, 1937– II. Title: World War Two at sea. D770.W66 2011 940.54'503—dc23 2011042142 ISBN: 978-1-59884-457-3 EISBN: 978-1-59884-458-0 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America To Malcolm “Kip” Muir Jr., scholar, gifted teacher, and friend. This page intentionally left blank Contents About the Editor ix Editorial Advisory Board xi List of Entries xiii Preface xxiii Overview xxv Entries A–Z 1 Chronology of Principal Events of World War II at Sea 823 Glossary of World War II Naval Terms 831 Bibliography 839 List of Editors and Contributors 865 Categorical Index 877 Index 889 vii This page intentionally left blank About the Editor Spencer C. -

Status of Leyte Gulf Fisheries Cys 2001-2011

Status of Leyte Gulf Fisheries CYs 2001-2011 Item Type article Authors Francisco, Miriam C.; Dayap, Nancy A.; Tumabiene, Lea A.; Francisco, Ruben Sr. A.; Candole, Mizpah Jay; De Veyra, Jaye Hanne; Bautista, Elmer DOI 10.31398/tpjf/25.1.2017C0011 Download date 27/09/2021 05:51:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/40965 The Philippine Journal of Fisheries 25Volume (1): 136-155 24 (1-2): _____ January-June 2018 JanuaryDOI 10.31398/tpjf/25.1.2017C0011 - December 2017 Status of Leyte Gulf Fisheries CYs 2001-2011 Miriam C. Francisco1, Nancy A. Dayap1, Lea A. Tumabiene1,*, Ruben A. Francisco, Sr., Mizpah Jay Candole1, Jaye Hanne De Veyra1, Elmer Bautista1 1Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Regional Office No. 08 Maharlika Highway, Brgy. Diit, Tacloban City ABSTRACT Leyte Gulf is among the major fishing grounds in the Philippines with a shelf area of 13, 147 km2 covering the islands of Samar and Leyte. For this reason, it was chosen as the study area in Eastern Visayas under the National Stock Assessment Program (NSAP) which aims to assess the status of fisheries resources. This paper presents the fishery stock assessment results from CY 2001-2011. The annual fish catch from 2001-2011 showed a declining trend. The lowest was in 2008 with 12, 483.52 MT while the highest was in 2003 with 26,367.32 MT. The municipal fisheries had a high catch contribution except in 2001 where commercial catch was higher by 30%. Thirty eight (38) types of fishing gears were identified operating in Leyte Gulf. -

World at War and the Fires Between War Again?

World at War and the Fires Between War Again? The Rhodes Colossus.© The Granger Collection / Universal Images Group / ImageQuest 2016 These days there are very few colonies in the traditional sense. But it wasn't that long ago that colonialism was very common around the world. How do you think your life would be different if this were still the case? If World War II hadn’t occurred, this might be a reality. As you've already learned, in the late 19th century, European nations competed with one another to grab the largest and richest regions of the globe to gain wealth and power. The imperialists swept over Asia and Africa, with Italy and France taking control of large parts of North Africa. Imperialism pitted European countries against each other as potential competitors or threats. Germany was a late participant in the imperial game, so it pursued colonies with a single-minded intensity. To further its imperial goals, Germany also began to build up its military in order to defend its colonies and itself against other European nations. German militarization alarmed other European nations, which then began to build up their militaries, too. Defensive alliances among nations were forged. These complex interdependencies were one factor that led to World War I. What Led to WWII?—Text Version Review the map description and the descriptions of the makeup of the world at the start of World War II (WWII). Map Description: There is a map of the world. There are a number of countries shaded four different colors: dark green, light green, blue, and gray. -

The Eagle's Webbed Feet

The Eagle’s Webbed Feet The Eagle’s Webbed Feet •A Maritime History of the United States A Maritime History of the United States A Maritime History of the Uniteds The Second World War “Scratch one flattop!” “Damn it Captain, they’re getting away!” Pearl Harbor • China is the real bone of contention between the US and Japan • May 1941, Roosevelt orders the fleet to remain in Pearl Harbor • July 1941 – Oil imports to Japan halted • Japanese decision to go southeast for resources • The Soviet-Japanese Border Wars (1932-1939) o Battles of Khalkhin Gol (Nomonhan) (May-Sept 1939) o Neutrality Pact (April 1941) • The Philippines is the real target of the Pearl Harbor attack • Mahan’s influence on the IJN. “If you attack us, we will break your empire; before we are through with you …. we will crush you.” Admiral Stark (CNO) to Ambassador Nomura (Nov 1941) • What were the Japanese thinking? (Compromise Peace) Pearl Harbor (2) • Destroyed or severely damaged 8 battleships, 10 cruisers/destroyers, 230 aircraft, & killed 2400 men. Cost was 29 planes, 5 midget subs. • A “short war” meant they could ignore fuel depots, repair facilities and the submarine base. • Their air superiority meant they could ignore the US carriers • War declared on Japan the next day • On December 11th Germany declared war on the US (???) • One of the two stupidest decisions of World War Two USS Arizona USS Shaw War in the Atlantic • The US Navy’s role in the Atlantic War was: • The U-Boat War (Priority #1) • Safely convoying troops, equipment, and supplies • Destroy the U-Boat fleet • Conduct amphibious operations of Army forces • Because of Pearl Harbor, the Navy reluctantly supported the “Germany First” policy envisioned in Rainbow Five but it did not really believe in it. -

Spring Flowers and Hello April Showers! Will Only Attract Unattractive and Unwelcoming This Has to Be the Most Pleasant and Awakening Shoppers (And Theives)

Remember: Social Time! Come early at 6:30 to enjoy some cookies and soft drinks, and chat with neighbors before the meeting starts. April 2012 Volume 19 Issue 2 Next General Neighborhood Meeting: Thursday, April 19 6:30 pm Social Gathering (Soft drinks and cookies provided) 7:00 pm Quarterly WNNA General Meeting Orion Ballroom, 15th floor, Bank of America Building President’s Voice JOSEPH HERNANDEZ Welcome Spring flowers and hello April showers! will only attract unattractive and unwelcoming This has to be the most pleasant and awakening shoppers (and theives). Lastly, the greener we time of year. I am continually amazed by residents make WNNA the better it will be for our future. that put so much effort into their homes and yards. As you may recall, there were a number of trees The “sweat equity” we all invest in our properties planted in the greenbelt last year and we hope to is why its so easy to appreciate the neighborhood. have all new landscaping done in the Monssen and This year, I’m excited to serve as President and Woolsey triangles. If the funds allow, we’d like to pleased to be working with such a great board of add a few sections of landscape and flowers in volunteers that represent WNNA so well. There various areas throughout the greenbelts along has been some progress made with various North and South Manus. This long term plan will projects this year and still so much left to do to eventually play a critical role in selling make Wynnewood North a safer, cleaner and Wynnewood North, increasing real estate traffic, greener place to live. -

I Had Well Over 1000 Hours of Time in the Air Before I

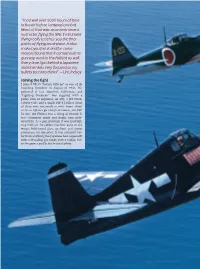

“I had well over 1,000 hours of time in the air before I entered combat. Most of that was as an instrument instructor fl ying the SNJ. Instrument fl ying really teaches you the fi ner points of fl ying an airplane. It also makes you focus and for some reason I found that it carried over to gunnery work in the Hellcat as well. Every time I got behind a Japanese airplane I was very focused as my bullets tore into them!” —Lin Lindsay Joining the fi ght I joined VF-19 “Satan’s Kittens” as one of its founding members in August of 1943. We gathered at Los Alamitos, California, and “Fighting Nineteen” was supplied with a paltry sum of airplanes; an SNJ, a JF2 Duck, a Piper Cub, and a single F6F-3 Hellcat. Most of them were not much to write home about as far as fi ghters go except of course, the F6F. To me, the Hellcat was a thing of beauty. It was Grumman made and damn near inde- structible! As a gun platform it was hard hit- ting with six .50 caliber machine guns in the wings, bulletproof glass up front and armor protection for the pilot. It was certainly bet- ter than anything the Japanese had, especially with self-sealing gas tanks, better radios, bet- ter fi repower and better trained pilots. 24 fl ightjournal.com Bad Kitty.indd 24 5/10/13 11:51 AM Bad KittyVF-19 “Satan’s Kittens” Chew Up the Enemy BY ELVIN “LIN” LINDSAY, LT. -

October 2019 Newsletter

Freedom’s Voice The Monthly Newsletter of the Military History Center 112 N. Main ST Broken Arrow, OK 74012 http://www.okmhc.org/ “Promoting Patriotism through the Preservation of Military History” Volume 6, Number 10 October 2019 United States Armed Services Birthday Party for Junior Nipps Day of Observance On September 25, the MHC treated World War II veteran, Oscar Nipps, Jr., affectionately called Junior, to a 94th birthday Navy Birthday – October 13 th st party. Junior was a member of the 5 Cavalry Regiment, 1 Cavalry Division. He saw combat on Leyte and in the Battle of Manila. He also witnessed the surrender ceremony in Tokyo Important Dates Bay and spent a short time on occupation duty in Japan. November 10 – Salute to Veterans Concert The MHC will present its fifth annual Salute to Veterans Concert at Broken Arrow’s Kirkland Theater located at 808 E. College ST at 2:00 PM on Sunday, November 10. Maggie Bond, 2019 Miss Broken Arrow, will sing several patriotic and military songs of past eras. The concert will be high- lighted by the Tulsa Community Band, which will play pat- riotic music to honor all those who have served in our armed forces. Mr. Johnnie Parks, Broken Arrow City Coun- cilor, who served in the Honor Company, 3rd Infantry “Old Guard” Regiment, will be the guest speaker at the event. The Honor Company of the 3rd Infantry Regiment guards the Tombs of the Unknowns and conducts all funerals at Arlington National Cemetery. Mr. Parks served as a casket bearer in the Honor Company.