The Edmond De Rothschild Research Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel-Hizbullah Conflict: Victims of Rocket Attacks and IDF Casualties July-Aug 2006

My MFA MFA Terrorism Terror from Lebanon Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket attacks and IDF casualties July-Aug 2006 Search Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket E-mail to a friend attacks and IDF casualties Print the article 12 Jul 2006 Add to my bookmarks July-August 2006 Since July 12, 43 Israeli civilians and 118 IDF soldiers have See also MFA newsletter been killed. Hizbullah attacks northern Israel and Israel's response About the Ministry (Note: The figure for civilians includes four who died of heart attacks during rocket attacks.) MFA events Foreign Relations Facts About Israel July 12, 2006 Government - Killed in IDF patrol jeeps: Jerusalem-Capital Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Eyal Benin, 22, of Beersheba Treaties Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Shani Turgeman, 24, of Beit Shean History of Israel Sgt.-Maj. Wassim Nazal, 26, of Yanuah Peace Process - Tank crew hit by mine in Lebanon: Terrorism St.-Sgt. Alexei Kushnirski, 21, of Nes Ziona Anti-Semitism/Holocaust St.-Sgt. Yaniv Bar-on, 20, of Maccabim Israel beyond politics Sgt. Gadi Mosayev, 20, of Akko Sgt. Shlomi Yirmiyahu, 20, of Rishon Lezion Int'l development MFA Publications - Killed trying to retrieve tank crew: Our Bookmarks Sgt. Nimrod Cohen, 19, of Mitzpe Shalem News Archive MFA Library Eyal Benin Shani Turgeman Wassim Nazal Nimrod Cohen Alexei Kushnirski Yaniv Bar-on Gadi Mosayev Shlomi Yirmiyahu July 13, 2006 Two Israelis were killed by Katyusha rockets fired by Hizbullah: Monica Seidman (Lehrer), 40, of Nahariya was killed in her home; Nitzo Rubin, 33, of Safed, was killed while on his way to visit his children. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Conversation About Life in Kamenka, 1920S-1940S Written by Elisha Roith, Israel

Conversation about life in Kamenka, 1920s-1940s Written by Elisha Roith, Israel On August 3, 2002, Ofra Zilbershats invited the surviving children of Tsipa Shlafer and Mordekhai Perlman. Rokhele and Manya were already deceased, at that time. Judith participated in the conversation, at the age of 94, Borya was 92 years old, and Sarah was 85. Additional participants were their daughters Dalia, Ofra, and Amira, their spouses, and Elisha, the 'senior grandchild,' Rokhele's son. Elisha began the meeting, attempting to delineate the parameters of the dialogue, and the sequence of events. He concluded his remarks in stating that "in Kaminka, there were some pogroms, a bit of revolution…" Borya: Some?! I remember a lot!... they called it a street there 'Yendrot' - the other street, that is how they called it. Judith: That was also the main street. Borya: And I should quite like to go there, and wish I could merit reciting qaddish over the grave of Grandmother and Grandfather. My grandmother was killed in front of me, I saw her, and how they murdered her - and the reason that I saw her... it was a pogrom. Elisha: Whose? By Petlura? Borya: No, no. By Denikin. We ran off, we had some Christian neighbors who were not bad; we escaped to their house, and they hid us. Grandmother was with us, and at noon, she suddenly said, "I need to see what is going on there." She wanted to see if the house was still in order, if it yet stood. I said... I was still a child... We said, "No. -

Palestine About the Author

PALESTINE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Professor Nur Masalha is a Palestinian historian and a member of the Centre for Palestine Studies, SOAS, University of London. He is also editor of the Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. His books include Expulsion of the Palestinians (1992); A Land Without a People (1997); The Politics of Denial (2003); The Bible and Zionism (Zed 2007) and The Pales- tine Nakba (Zed 2012). PALESTINE A FOUR THOUSAND YEAR HISTORY NUR MASALHA Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History was first published in 2018 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK. www.zedbooks.net Copyright © Nur Masalha 2018. The right of Nur Masalha to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by seagulls.net Index by Nur Masalha Cover design © De Agostini Picture Library/Getty All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑272‑7 hb ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑274‑1 pdf ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑275‑8 epub ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑276‑5 mobi CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 1. The Philistines and Philistia as a distinct geo‑political entity: 55 Late Bronze Age to 500 BC 2. The conception of Palestine in Classical Antiquity and 71 during the Hellenistic Empires (500‒135 BC) 3. -

History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948)

History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948) A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arabic and Islamic Studies By Seraje Assi, M.A. Washington, DC May 30, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Seraje Assi All Rights Reserved ii History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948) Seraje Assi, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Judith Tucker, Ph.D. ABSTRACT My research examines contending visions on nomadism in modern Palestine. It is a comparative study that covers British, Arab and Zionist attitudes to nomadism. By nomadism I refer to a form of territorialist discourse, one which views tribal formations as the antithesis of national and land rights, thus justifying the exteriority of nomadism to the state apparatus. Drawing on primary sources in Arabic and Hebrew, I show how local conceptions of nomadism have been reconstructed on new legal taxonomies rooted in modern European theories and praxis. By undertaking a comparative approach, I maintain that the introduction of these taxonomies transformed not only local Palestinian perceptions of nomadism, but perceptions that characterized early Zionist literature. The purpose of my research is not to provide a legal framework for nomadism on the basis of these taxonomies. Quite the contrary, it is to show how nomadism, as a set of official narratives on the Bedouin of Palestine, failed to imagine nationhood and statehood beyond the single apparatus of settlement. iii The research and writing of this thesis is dedicated to everyone who helped along the way. -

Jugendbegegnung 2011

Deutsch-Israelische Region Unter Galiläa Jugendbegegnung 2011 15.07. – 26.07 16.10 – 26.10. in in Hannover Unter Galiläa Deutsch/Israelische Jugendbegegnung 15.7.-26.7.2011 in Region Hannover und Berlin 16.10.-26.10.2011 in Region Unter Galiläa und Jerusalem Der Dank gilt den Veranstaltern und den Unterstützern Region Unter Galiläa Naturfreunde Hannover 1 Programmerstellung und Organisation in Deutschland: Imke Eckhardt, Region Hannover Ute Pilling (ehrenamtlich, Ambassador for Peace Springe e.V.) Begleitung und Betreuung der Gruppe in Deutschland und Israel: Markus Fockenbrock, Region Hannover Margo Blödorn (ehrenamtlich, VfV Concordia Alvesrode e.V.) Programmerstellung in Israel: Yossi Bar Sheshet Begleitung und Betreuung in Deutschland und Israel Ari David Movsowitz, Region Unter Galiläa Rachel Aslan, Region Unter Galiläa Texte: Nadine Krombass (Teilnehmerin, 19 Jahre) Bilder: Christian Gohdes (Teilnehmer, 18 Jahre) und übrige Teilnehmende Teilnehmende der Begegnungen: Deutsche Teilnehmer: Israelische Teilnehmer: • Silke Andreas • Amit Levy • Lina Blum • Gony Mubar Ashin • Fiene Blum • Noam Tal • Chantal Boltz • Nofar Edelshtein • Johanna Ernst • Dan Kroviarski • Sarah Feldmann • Moshe Shmueli • Johanne Gohdes • Moti Shubert • Christian Gohdes • Idan Freundlich • Nadine Krombass • Yonatan Shoshan • Franziska Spitznagel • Amit Harpaz 2 Bericht über den Jugendbegegnung Region Hannover/Region Unter Galiläa/Israel in der Region Hannover und Berlin- 15.7.–26.7.2011 geschrieben von Nadine Krombass (Teilnehmerin) 15. Juli: Die Vorfreude ist groß, denn heute lernen wir, die deutsche Gruppe des Austauschs, endlich unsere israelischen Austauschpartner kennen, mit denen wir die nächsten 10 Tage verbringen werden. Aber wer sind eigentlich „wir“? Zum größten Teil kannte sich die deutsche Gruppe noch gar nicht, deswegen trafen wir uns alle im Naturfreundehaus, bevor es an das Abholen der anderen ging. -

Ilan Pappé Zionism As Colonialism

Ilan Pappé Zionism as Colonialism: A Comparative View of Diluted Colonialism in Asia and Africa Introduction: The Reputation of Colonialism Ever since historiography was professionalized as a scientific discipline, historians have consid- ered the motives for mass human geographical relocations. In the twentieth century, this quest focused on the colonialist settler projects that moved hundreds of thousands of people from Europe into America, Asia, and Africa in the pre- ceding centuries. The various explanations for this human transit have changed considerably in recent times, and this transformation is the departure point for this essay. The early explanations for human relocations were empiricist and positivist; they assumed that every human action has a concrete explanation best found in the evidence left by those who per- formed the action. The practitioners of social his- tory were particularly interested in the question, and when their field of inquiry was impacted by trends in philosophy and linguistics, their conclusion differed from that of the previous generation. The research on Zionism should be seen in light of these historiographical developments. Until recently, in the Israeli historiography, the South Atlantic Quarterly 107:4, Fall 2008 doi 10.1215/00382876-2008-009 © 2008 Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/south-atlantic-quarterly/article-pdf/107/4/611/470173/SAQ107-04-01PappeFpp.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 612 Ilan Pappé dominant explanation for the movement of Jews from Europe to Palestine in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was—and, in many ways, still is—positivist and empiricist.1 Researchers analyzed the motives of the first group of settlers who arrived on Palestine’s shores in 1882 according to the testimonies in their diaries and other documents. -

Hiking the Jesus Trail: and Other Biblical Walks in the Galilee Free Download

HIKING THE JESUS TRAIL: AND OTHER BIBLICAL WALKS IN THE GALILEE FREE DOWNLOAD Anna Dintaman,David Landis | 256 pages | 20 Feb 2013 | Village to Village Press | 9780984353323 | English | Hasleysville, United States Hiking the Jesus Trail and Other Biblical Walks in the Galilee One day I packed my life and started traveling… except I packed too much. Jan rated it it was amazing Jul 17, Having this book and… more. Geir Dolmen. The good thing is that Moshav Arbel is actually visible from the hills around the Horns of Hattin, so you may cut through the olive groves to reach the village for the night. The best part of it is that it also is a hotel! The remains of these villages are not immediately visible — quite often, the abandoned villages have been buried and forests were planted over the ruins. Comfortably dressed for the Jesus Trail in my Kuhl clothes. Stayed at the Wedding Guest House in Cana and it was okay. Due to its connection to Christianity, Nazareth is a major tourist spot for groups of pilgrims. David Landis. So make sure to refill water bottles and get food before getting on the actual trail. It takes around 3 and a half hour to get there. There are male and female dorms and also double rooms. The first day of the trail usually begins in Jesus's hometown of Nazareth and continues down to Sepphoris National Park, the main Roman city when Jesus was growing up. Other Editions Hiking the Jesus Trail: And Other Biblical Walks in the Galilee. -

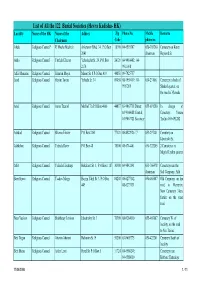

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Prayer for the State of Israel 166 Prayer for the Welfare of Israel’S Soldiers 168 Hatikvah

Edited by Rabbi Tuly Weisz The Israel Bible: Numbers First Edition, 2018 Menorah Books An imprint of Koren Publishers Jerusalem Ltd. POB 8531, New Milford, CT 06776-8531, USA & POB 4044, Jerusalem 9104001, Israel www.menorahbooks.com The Israel Bible was produced by Israel365 in cooperation with Teach for Israel and is used with permission from Teach for Israel. All rights reserved. The English translation was adapted by Israel365 from the JPS Tanakh. Copyright © 1985 by the Jewish Publication Society. All rights reserved. Cover image: © Seth Aronstam - https://www.setharonstam.com/ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews. The Israel Bible is a holy book that contains the name of God and should be treated with respect. Table of Contents iv Credits v Acknowledgements viii Aleph Bet Chart ix Introduction xv Foreward xviii Blessing Before and After Reading theTorah 19 The Book of Numbers 129 Biographies of The Israel Bible Scholars 131 Bibliography 142 List of Transliterated Words in The Israel Bible 157 Photo Credits 158 Chart of the Hebrew Months and their Holidays 161 Map of Modern-Day Israel and its Neighbors 162 List of Prime Ministers of the State of Israel 163 Prayer for the State of Israel 166 Prayer for the Welfare of Israel’s Soldiers 168 Hatikvah iii Credits -

Municipal Amalgamation in Israel

TAUB CENTER for Social Policy Studies in Israel Municipal Amalgamation in Israel Lessons and Proposals for the Future Yaniv Reingewertz Policy Paper No. 2013.02 Jerusalem, July 2013 TAUB CENTER for Social Policy Studies in Israel The Taub Center was established in 1982 under the leadership and vision of Herbert M. Singer, Henry Taub, and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. The Center is funded by a permanent endowment created by the Henry and Marilyn Taub Foundation, the Herbert M. and Nell Singer Foundation, Jane and John Colman, the Kolker-Saxon-Hallock Family Foundation, the Milton A. and Roslyn Z. Wolf Family Foundation, and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. This volume, like all Center publications, represents the views of its authors only, and they alone are responsible for its contents. Nothing stated in this book creates an obligation on the part of the Center, its Board of Directors, its employees, other affiliated persons, or those who support its activities. Translation: Ruvik Danieli Editing and layout: Laura Brass Center address: 15 Ha’ari Street, Jerusalem Telephone: 02 5671818 Fax: 02 5671919 Email: [email protected] Website: www.taubcenter.org.il ◘ Internet edition Municipal Amalgamation in Israel Lessons and Proposals for the Future Yaniv Reingewertz Abstract This policy paper deals with municipal amalgamations in Israel, and puts forward a concrete proposal for merging 25 small municipalities with adjacent ones. According to an estimate based on the results of the municipal amalgamations reform carried out in Israel in 2003 (Reingewertz, 2012), thanks to the economies of scale in providing public services, these unifications are expected to generate savings of approximately NIS 131 million per annum.