The Tantalizing Aroma of Citrus Blossoms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission Report Ref.Code: 9N15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44

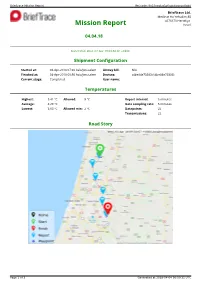

Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Brieftrace Ltd. Medinat Ha-Yehudim 85 4676670 Herzeliya Mission Report Israel 04.04.18 clalit Status: Success Generated: Wed, 04 Apr 18 09:50:31 +0300 Shipment Configuration Started at: 04-Apr-2018 07:30 Asia/Jerusalem Airway bill: N/A Finished at: 04-Apr-2018 09:50 Asia/Jerusalem Devices: c4be84e73383 (c4be84e73383) Current stage: Completed User name: Shai Temperatures Highest: 5.41 °C Allowed: 8 °C Report interval: 5 minutes Average: 4.29 °C Data sampling rate: 5 minutes Lowest: 3.63 °C Allowed min: 2 °C Datapoints: 22 Transmissions: 22 Road Story Page 1 of 3 Generated at 2018-04-04 06:50:31 UTC Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Report Data 13 ° 12 ° 11 ° 10 ° 9 ° Allowed high: 8° C 8 ° C 7 ° ° High e r 6 ° Max: 5.41° C u t a 5 ° r Low e p 4 ° Min: 3.63° C m e 3 ° T Allowed low: 2° C 2 ° 1 ° 0 ° -1 ° -2 ° -3 ° 07:30 07:45 08:00 08:15 08:30 08:45 09:00 09:15 09:30 09:45 Date and time. All times are in Asia/Jerusalem timezone. brieftrace.com Tracker Time Date Temp°CAlert? RH % Location Control Traceability c4be84e73383 07:30 04-04-2018 4.26 79.65 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636158 dfb902 c4be84e73383 07:36 04-04-2018 4.24 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636161 b23bc8 c4be84e73383 07:43 04-04-2018 4.21 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636167 c1c01c c4be84e73383 07:49 04-04-2018 4.18 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636176 4a3752 c4be84e73383 07:56 04-04-2018 4.21 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

A Physiological Study of Carotenoid Pigments and Other Constituents In

~ 12.8 ~W 1.0 w ~ W 1.0 Ii& W ~W ~W .2 w ~ LI:~ Ll:1i£ '"11 ~ iii ...~ .. ~ ...~ .. ~ 1111,1.1 iii.... 1.1 ...... 4 11111 1.25 '"'' 1.4 111111.6 111111.25 ""'1. 111111.6 . ,/ MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAL BUREAU OF· STANDAROS-1963-A NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDAROS-1963-A · -\ Technical Bulletin No. 780 April 1941 .. :JJ~'D.D§,.;&.S.,·" . ~• .BP~.IW!t'.'~GB.ilJ~T\IJi.E ·'~.f&~.JNG1&O~~:••<C:;. -, ". "' '. '.', '. ~ A Physiological Study of Carotenoid Pig ments and Other Constituents in the Juice of Florida Oranges 1 By ERSTON V. MrLI,EH, physiologist, ,J. H. WlNH'I'ON, senior horticultllrist, alld D. F. FlSIIE1t, principal iwrticllitllriH/, lJivision oj Frzd! a'lu! \"cgciablc Crops and Diseases, Bureau oj lJlant hull/siry 2 COi\TL\TS IJnf!C Hp~ults~('ontiIlIl('d. Pu~c Lntroduction .......___ ••__ •••-.___ ,_ ..•...._. 1 I"["('t uf loenJity all Jli~rJll'lltntioIL _,,_.__ •• 13 Litl"rntufl:' f('view. _ 'l l{(Jut..".tockamIIJil!uwnts ,~~_.~_~~ .. 13 Materials nnd lIlethods 2 ~[a~iJIIllm l'arotcnoid eontl~nt or juicp of aJl Descriptioll of Sllll1pll's 2 varirtirs _ H 'I'otal "arotl'lloid$ ill llw. jui('" ·1 CnfotNloids nnd OtlWf ('onstitu('nts of the Xanthophyll. _. fi juiee _____ .~__ 16 :;npouiflnblL' fraction.. .5 ])is('lIssion.. " 28 H~sull5.- 6 SUlIllIlary . ~ _ 30 SrasoI1ul ('hungl's in llig-nwnlS.. ti l.itt'rnturf1 (liw<i :H INTl{OOUCTlOl\ During Ul(' <'OLU'S!' oJ t'ur-iil'l' work hy tll!' pn'sent writel's on til(' pig mell ts ill ei trLls rind;:; (1 n;~li-·;l7), preliminnry IllHll.ySl'S ind iell-ted that lll,Llch of thl' 'yellow ('olor in tllP On1ng<' fh'sh is (it:(' to othp['-solublt' or t'1U:Qtcnoid pipu('lIts. -

The Edmond De Rothschild Research Series

The Edmond de Rothschild Research Series A collection of studies in the area of: Baron de Rothschild's ("Hanadiv's") Legacy 2018 The Edmond de Rothschild Research Series A collection of studies in the area of: Baron de Rothschild's ("Hanadiv's") Legacy 2018 Dear Partners, The Edmond de Rothschild Foundation (Israel) is spearheading philanthropic dedication to building an inclusive society by promoting excellence, diversity and leadership through higher education. Catalyzing true change and developing a cohesive society through dozens of innovative projects across the country, the Foundation provides growth and empowerment opportunities to the many communities in Israel. We develop and support novel solutions and creative partnerships, while evaluating result-driven programs with true social impact. In keeping with its philosophy of strategic philanthropy, the Foundation established the Edmond de Rothschild Research Series, to promote excellence in research and expand the knowledge in the Foundation’s areas of interest. The booklet before you centers on Baron de Rothschild's ("Hanadiv's") Legacy, as part of the first research series which focused on three main areas: 1. Access to and Success in Higher Education: As part of its efforts to reduce social gaps, the Foundation strives to insure access to and success in higher education for periphery populations. It supports programs aimed at improving access to higher education options through preparation and guidance, reducing academic student dropout rates, and translating graduates’ education into commensurate employment. 2. Measurement and Evaluation: The Foundation seeks to constantly enhance its social impact and therefore, emphasizes measurement and evaluation of the projects it supports according to predefined, coherent criteria. -

Vertical Surface & Seating Upholstery

Omni-R Price Group 1 Vertical Surface & Seating Upholstery Coconut J535 Cloud J521 Nickel J544 Ebony J501 Tangerine J537 Cork J517 Malt J547 Rhino J508 Crimson J502 Cocoa J509 Maize J518 Wasabi J543 Scarlet J538 Hydrangea J515 Blue Jay J541 Azure Blue J513 Sapphire J506 Ink Blue J507 Otto Price Group 1 Vertical Surface & Seating Upholstery Smoke K612 Bluestone K611 Ash K614 Aubergine K609 Honey K605 Coral K606 Iron K613 Charcoal K615 Merlot K608 Saffron K607 Grass K604 Olive K603 Lagoon K610 Peacock K601 Lizard K602 Spruce Price Group 1 Vertical Surface & Seating Upholstery Sliver Grey S803 Lunar Rock S115 Stone S014 Black S009 Bungee Cord S119 Plaza Taupe S106 Frost Gray S038 Dark Gull Gray S046 Gold Fusion S117 Misted Yellow S805 Lime S031 Olive S802 Tomato S003 Jaffa Orange S018 Ethereal Blue S112 Forest Green S108 Jester Red S017 Orient Blue S110 Blue Indigo S004 Stone Wash S023 Dutch Blue S005 Estate blue S026 Blue Mirage S019 Mirage Price Group 1 Vertical Surface (For India only, Lexicon only) Tangerine MI06 Cork MI04 Coconut MI09 Nickel MI02 Scarlet MI07 Malt MI01 Blue Jay MI05 Wasabi MI03 Azure Blue MI08 Hydrangea MI10 Buzz 2 Price Group 2 Vertical Surface & Seating Upholstery Alpine 5G64 Sable 5G51 Tornado 5G65 Black 5F17 Pumpkin 5G55 Stone 5F15 Meadow 5G59 Navy 5F08 Burgundy 5F05 Rouge 5G57 Blue 5F07 Cogent Connect Price Group 2 Vertical Surface & Seating Upholstery Coconut 5S15 Nickel 5S24 Stormcloud 5SF3 Graphite 5S25 Turmeric 5S16 Malt 5S27 Quicksilver 5S96 Root Beer 5S28 Tangerine 5S17 Rose Quartz 5SD6 Lagoon 5SD3 Citrine -

Sukkot Real Estate Magazine

SUKKOT 2020 REAL ESTATE Rotshtein The next generation of residential complexes HaHotrim - Tirat Carmel in Israel! In a perfect location between the green Carmel and the Mediterranean Sea, on the lands of Kibbutz HaHotrim, adjacent to Haifa, the new and advanced residential project Rotshtein Valley will be built. An 8-story boutique building complex that’s adapted to the modern lifestyle thanks to a high premium standard, a smart home system in every apartment and more! 4, 5-room apartments, garden Starting from NIS apartments, and penthouses Extension 3 GREEN CONSTRUCTION *Rendition for illustration only Rotshtein The next generation of residential complexes HaHotrim - Tirat Carmel in Israel! In a perfect location between the green Carmel and the Mediterranean Sea, on the lands of Kibbutz HaHotrim, adjacent to Haifa, the new and advanced residential project Rotshtein Valley will be built. An 8-story boutique building complex that’s adapted to the modern lifestyle thanks to a high premium standard, a smart home system in every apartment and more! 4, 5-room apartments, garden Starting from NIS apartments, and penthouses Extension 3 GREEN CONSTRUCTION *Rendition for illustration only Living the high Life LETTER FROM THE EDITOR TABLE OF CONTENTS Dear Readers, With toWers Welcome to the Sukkot edition of The Jerusalem THE ECONOMY: A CHALLENGING CONUNDRUM ....................08 Post’s Real Estate/Economic Post magazine. Juan de la Roca This edition is being published under the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic. Although not all the articles herein are related to the virus, it is a reality BUILDING A STRONGER FUTURE ............................................... 12 that cannot be ignored. -

Conversation About Life in Kamenka, 1920S-1940S Written by Elisha Roith, Israel

Conversation about life in Kamenka, 1920s-1940s Written by Elisha Roith, Israel On August 3, 2002, Ofra Zilbershats invited the surviving children of Tsipa Shlafer and Mordekhai Perlman. Rokhele and Manya were already deceased, at that time. Judith participated in the conversation, at the age of 94, Borya was 92 years old, and Sarah was 85. Additional participants were their daughters Dalia, Ofra, and Amira, their spouses, and Elisha, the 'senior grandchild,' Rokhele's son. Elisha began the meeting, attempting to delineate the parameters of the dialogue, and the sequence of events. He concluded his remarks in stating that "in Kaminka, there were some pogroms, a bit of revolution…" Borya: Some?! I remember a lot!... they called it a street there 'Yendrot' - the other street, that is how they called it. Judith: That was also the main street. Borya: And I should quite like to go there, and wish I could merit reciting qaddish over the grave of Grandmother and Grandfather. My grandmother was killed in front of me, I saw her, and how they murdered her - and the reason that I saw her... it was a pogrom. Elisha: Whose? By Petlura? Borya: No, no. By Denikin. We ran off, we had some Christian neighbors who were not bad; we escaped to their house, and they hid us. Grandmother was with us, and at noon, she suddenly said, "I need to see what is going on there." She wanted to see if the house was still in order, if it yet stood. I said... I was still a child... We said, "No. -

History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948)

History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948) A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arabic and Islamic Studies By Seraje Assi, M.A. Washington, DC May 30, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Seraje Assi All Rights Reserved ii History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948) Seraje Assi, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Judith Tucker, Ph.D. ABSTRACT My research examines contending visions on nomadism in modern Palestine. It is a comparative study that covers British, Arab and Zionist attitudes to nomadism. By nomadism I refer to a form of territorialist discourse, one which views tribal formations as the antithesis of national and land rights, thus justifying the exteriority of nomadism to the state apparatus. Drawing on primary sources in Arabic and Hebrew, I show how local conceptions of nomadism have been reconstructed on new legal taxonomies rooted in modern European theories and praxis. By undertaking a comparative approach, I maintain that the introduction of these taxonomies transformed not only local Palestinian perceptions of nomadism, but perceptions that characterized early Zionist literature. The purpose of my research is not to provide a legal framework for nomadism on the basis of these taxonomies. Quite the contrary, it is to show how nomadism, as a set of official narratives on the Bedouin of Palestine, failed to imagine nationhood and statehood beyond the single apparatus of settlement. iii The research and writing of this thesis is dedicated to everyone who helped along the way. -

Ziv Medical Center Greets the New Director Farewell to Prof

Ziv Newsletter January 2015 Best wishes for a healthy and peaceful 2015 to our friends and benefactors in Israel and around the world. Ziv Medical Center Greets the New Director Farewell to Prof. Oscar Embon Dr. Salman Zarka graduated After 21 years as Director of Ziv from the Faculty of Medicine, Medical Center, Prof. Oscar Embon Technion – Israel Institute of leaves Ziv Medical Center satisfied Technology, Haifa in 1988. He that much has been accomplished received a Master's degree in during his tenure. Prof. Embon, Public Health (MPH) from the faced the challenges of managing Hebrew University of Jerusalem, a hospital in northern Israel, and an additional Master's degree characterized by the complex needs of the region's unique in Political Science from the mosaic of residents as well as those resulting from the University of Haifa. hospital's proximity to both the Lebanese and Syrian borders. Prior to his position at Ziv, Dr. Zarka served as a Colonel in the "Among the projects I am most thrilled about are the I.D.F. for 25 years in a variety of positions, the last of which was construction of the Child Health Center and the Radiotherapy commander of the Military Health Services Department. Previous Unit. The Child Health Center is going to be a magnificent state- to this position, Dr. Zarka was the Head of the Medical Corps of of-the-art partially reinforced building, which will house all of the Northern Command and the Commander of the Military Field the services essential for top quality treatment of children, as Hospital for the Syrian casualties in the Golan Heights. -

ISRAEL Dan to Beersheba Study Tour March 28 - April 7, 2022

Presents... ISRAEL Dan to Beersheba Study Tour March 28 - April 7, 2022 International Board of Jewish Missions 5106 Genesis Lane | Hixson, TN 37343 ISRAEL Dan to Beersheba Sudy Tour Monday • March 28 – Depart from April 5 – Jerusalem Atlanta, GA Mount Moriah, Dome of the Rock, Mount of Olives, Garden of Gethsemane, Pool of Bethesda, Stephen’s March 29 – Arrive in Israel Gate, Church of Saint Anne, Golgotha (place of the Experience Project Nehemiah (a humanitarian outreach skull), Garden Tomb, and the Valley of Elah (where to Jewish immigrants) and the ancient seaport city of David slew Goliath). Overnight at Sephardic House in Jaffa (the house of Simon the Tanner). Overnight near Old City, Jerusalem. the Mediterranean Coast in the city of Netanya. April 6 – Negev Desert and Journey Home March 30 – Sharon Plain & Jezreel Valley Home of David Ben Gurion (the first prime minister Ancient Caesarea Maritime (where Peter preached of the modern State of Israel), Ramon Crater, farewell the gospel to the household of Cornelius). Mount dinner, and Ben Gurion Airport. Carmel, the Jezreel Valley, and Megiddo (the site of 21 battles from the Old Testament and the final battle of Thursday • April 7 – Journey home Armageddon). Overnight at Ginosar Kibbutz Hotel on to the USA the Sea of Galilee. Pricing: March 31 – The Galilee • $3,900 per passenger (double occupancy) Nazareth (including the Nazareth Village, a wonderful • Single Supplement —add $700 re-creation of what the village would have looked • Minimum 20 passengers like in biblical times), Capernaum, a cruise on the Sea of Galilee, Magdala (home of Mary Magdalene), and the Includes: Jordan River. -

Ilan Pappé Zionism As Colonialism

Ilan Pappé Zionism as Colonialism: A Comparative View of Diluted Colonialism in Asia and Africa Introduction: The Reputation of Colonialism Ever since historiography was professionalized as a scientific discipline, historians have consid- ered the motives for mass human geographical relocations. In the twentieth century, this quest focused on the colonialist settler projects that moved hundreds of thousands of people from Europe into America, Asia, and Africa in the pre- ceding centuries. The various explanations for this human transit have changed considerably in recent times, and this transformation is the departure point for this essay. The early explanations for human relocations were empiricist and positivist; they assumed that every human action has a concrete explanation best found in the evidence left by those who per- formed the action. The practitioners of social his- tory were particularly interested in the question, and when their field of inquiry was impacted by trends in philosophy and linguistics, their conclusion differed from that of the previous generation. The research on Zionism should be seen in light of these historiographical developments. Until recently, in the Israeli historiography, the South Atlantic Quarterly 107:4, Fall 2008 doi 10.1215/00382876-2008-009 © 2008 Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/south-atlantic-quarterly/article-pdf/107/4/611/470173/SAQ107-04-01PappeFpp.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 612 Ilan Pappé dominant explanation for the movement of Jews from Europe to Palestine in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was—and, in many ways, still is—positivist and empiricist.1 Researchers analyzed the motives of the first group of settlers who arrived on Palestine’s shores in 1882 according to the testimonies in their diaries and other documents. -

Holdings of the University of California Citrus Variety Collection 41

Holdings of the University of California Citrus Variety Collection Category Other identifiers CRC VI PI numbera Accession name or descriptionb numberc numberd Sourcee Datef 1. Citron and hybrid 0138-A Indian citron (ops) 539413 India 1912 0138-B Indian citron (ops) 539414 India 1912 0294 Ponderosa “lemon” (probable Citron ´ lemon hybrid) 409 539491 Fawcett’s #127, Florida collection 1914 0648 Orange-citron-hybrid 539238 Mr. Flippen, between Fullerton and Placentia CA 1915 0661 Indian sour citron (ops) (Zamburi) 31981 USDA, Chico Garden 1915 1795 Corsican citron 539415 W.T. Swingle, USDA 1924 2456 Citron or citron hybrid 539416 From CPB 1930 (Came in as Djerok which is Dutch word for “citrus” 2847 Yemen citron 105957 Bureau of Plant Introduction 3055 Bengal citron (ops) (citron hybrid?) 539417 Ed Pollock, NSW, Australia 1954 3174 Unnamed citron 230626 H. Chapot, Rabat, Morocco 1955 3190 Dabbe (ops) 539418 H. Chapot, Rabat, Morocco 1959 3241 Citrus megaloxycarpa (ops) (Bor-tenga) (hybrid) 539446 Fruit Research Station, Burnihat Assam, India 1957 3487 Kulu “lemon” (ops) 539207 A.G. Norman, Botanical Garden, Ann Arbor MI 1963 3518 Citron of Commerce (ops) 539419 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio CA 1966 3519 Citron of Commerce (ops) 539420 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio CA 1966 3520 Corsican citron (ops) 539421 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio CA 1966 3521 Corsican citron (ops) 539422 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio CA 1966 3522 Diamante citron (ops) 539423 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio CA 1966 3523 Diamante citron (ops) 539424 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio