Buffalo Pebble Snail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lloyd Shoals

Southern Company Generation. 241 Ralph McGill Boulevard, NE BIN 10193 Atlanta, GA 30308-3374 404 506 7219 tel July 3, 2018 FERC Project No. 2336 Lloyd Shoals Project Notice of Intent to Relicense Lloyd Shoals Dam, Preliminary Application Document, Request for Designation under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act and Request for Authorization to Initiate Consultation under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act Ms. Kimberly D. Bose, Secretary Federal Energy Regulatory Commission 888 First Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20426 Dear Ms. Bose: On behalf of Georgia Power Company, Southern Company is filing this letter to indicate our intent to relicense the Lloyd Shoals Hydroelectric Project, FERC Project No. 2336 (Lloyd Shoals Project). We will file a complete application for a new license for Lloyd Shoals Project utilizing the Integrated Licensing Process (ILP) in accordance with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s (Commission) regulations found at 18 CFR Part 5. The proposed Process, Plan and Schedule for the ILP proceeding is provided in Table 1 of the Preliminary Application Document included with this filing. We are also requesting through this filing designation as the Commission’s non-federal representative for consultation under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act and authorization to initiate consultation under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. There are four components to this filing: 1) Cover Letter (Public) 2) Notification of Intent (Public) 3) Preliminary Application Document (Public) 4) Preliminary Application Document – Appendix C (CEII) If you require further information, please contact me at 404.506.7219. Sincerely, Courtenay R. -

Invasive Aquatic Species with the Potential to Affect the Great Sacandaga Lake Region

Invasive Aquatic Species with the Potential to Affect the Great Sacandaga Lake Region Tiffini M. Burlingame, Research Associate Lawrence W. Eichler, Research Scientist Charles W. Boylen, Associate Director Darrin Fresh Water Institute 5060 Lakeshore Drive Bolton Landing, NY 12814 TABLE OF CONTENTS FISH Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengu)s 3 Goldfish (Carassius auratus) 5 Northern Snakehead (Channa argus) 7 Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) 9 Eurasian Ruff (Gymnocephalus cernuus) 11 Brook Silverside (Labidesthes sicculus) 13 White Perch (Morone americana) 15 Round Goby (Neogobius melanostomus) 17 Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) 19 Sea Lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) 21 White Crappie (Pomoxis annularis) 23 Tubenose Goby (Proterorhinus marmoratus) 25 Brown Trout (Salmo trutta) 27 European Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus) 29 Tench (Tinca tinca) 31 PLANTS & ALGAE Ribbon Leaf Water Plantain (Alisma gramineum) 34 Flowering Rush (Butomus umbellatus) 36 Fanwort (Cabomba caroliniana) 38 Rock Snot (Didymosphenia geminata) 40 Brazilian Elodea (Egeria densa) 42 Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) 44 Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) 46 Frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae) 48 Yellow Flag Iris (Iris pseudacorus) 50 Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) 52 Water Clover (Marsilea quadrifolia) 54 Parrot Feather (Myriophyllum aquaticum) 56 Variable Leaf Milfoil (Myriophyllum heterophyllum) 58 Eurasian Water Milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) 60 Southern Naiad (Najas guadalupensis) 62 Brittle Naiad (Najas minor) 64 Starry Stonewort (Nitellopsis obtusa) 66 Yellow -

Fresh-Water Mollusks of Cretaceous Age from Montana and Wyoming

Fresh-Water Mollusks of Cretaceous Age From Montana and Wyoming GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 233-A Fresh-Water Mollusks of Cretaceous Age From Montana and Wyomin By TENG-CHIEN YEN SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY, 1950, PAGES 1-20 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 233-A Part I: A fluviatile fauna from the Kootenai formation near Harlowton, Montana Part 2: An Upper Cretaceous fauna from the Leeds Creek • area, Lincoln County', Wyoming UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1951 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 45 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Part 1. A fluviatile fauna from the Kootenai formation near Harlowton, Montana. _ 1 Abstract- ______________________________________________________________ 1 Introduction ___________________________________________________________ 1 Composition of the fauna, and its origin.._________________________________ 1 Stratigraphic position and correlations_______________________________---___ 2 Systematic descriptions.__________________________________________________ 4 Bibliography. __________________________________________________________ 9 Part 2. An Upper Cretaceous fauna from the Leeds Creek area, Lincoln County, Wyoming_________________________________________________________ 11 Abstract.__________________-_________________________-____:__-_-_---___ 11 Introduction ___________________________________________________________ -

Summary Report of Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5

Summary Report of Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5 Summary Report of Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5 Prepared by: Amy J. Benson, Colette C. Jacono, Pam L. Fuller, Elizabeth R. McKercher, U.S. Geological Survey 7920 NW 71st Street Gainesville, Florida 32653 and Myriah M. Richerson Johnson Controls World Services, Inc. 7315 North Atlantic Avenue Cape Canaveral, FL 32920 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 North Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22203 29 February 2004 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………... ...1 Aquatic Macrophytes ………………………………………………………………….. ... 2 Submersed Plants ………...………………………………………………........... 7 Emergent Plants ………………………………………………………….......... 13 Floating Plants ………………………………………………………………..... 24 Fishes ...…………….…………………………………………………………………..... 29 Invertebrates…………………………………………………………………………...... 56 Mollusks …………………………………………………………………………. 57 Bivalves …………….………………………………………………........ 57 Gastropods ……………………………………………………………... 63 Nudibranchs ………………………………………………………......... 68 Crustaceans …………………………………………………………………..... 69 Amphipods …………………………………………………………….... 69 Cladocerans …………………………………………………………..... 70 Copepods ……………………………………………………………….. 71 Crabs …………………………………………………………………...... 72 Crayfish ………………………………………………………………….. 73 Isopods ………………………………………………………………...... 75 Shrimp ………………………………………………………………….... 75 Amphibians and Reptiles …………………………………………………………….. 76 Amphibians ……………………………………………………………….......... 81 Toads and Frogs -

Freshwater Snails

Freshwater Snails Introduction Mollusks of the class Gastropoda, commonly known as snails and slugs, are found in freshwater, terrestrial and marine habitats. Terrestrial snails are not being included at this time because little is known about the distribution and status of these organisms. Further, we have been unable to identify any regional experts who can provide substantial information about South Carolina’s land snails. As with all invertebrate groups, snails and other gastropods are in need of taxonomic and genetic work. Knowledge of gastropods has suffered due to the scarcity of taxonomic experts in this area. A fairly extensive survey for freshwater snails has been conducted across South Carolina (Dillon 2004a). Specimens for this study were obtained both through stream collections and by identifying snails from previous aquatic invertebrate samples collected by South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (SC DHEC) for water quality assessment. We have little information on other aspects of the natural history of freshwater snails. Basic studies on their taxonomy, habitat requirements and response to potential threats should be encouraged. Summary Freshwater snails are a poorly understood group of organisms and we have little information on their sensitivity to particular threats. There are also taxonomic questions surrounding the classification of freshwater snails. The three snail species addressed in this section are classified below based on our level of conservation concern. Highest Priority Somatogyrus sp.: In addition to the fact that there are taxonomic questions regarding this species, it and its congeners are rare in South Carolina and throughout their ranges. This species may be sensitive to siltation and water quality degradation and its habitat is treatened by increasing development. -

At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas

David Moynahan | St. Marks NWR At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas National Wildlife Refuge Association Mark Sowers, Editor October 2017 1001 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 905, Washington, DC 20036 • 202-417-3803 • www.refugeassociation.org At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas Table of Contents Introduction and Methods ................................................................................................3 Results and Discussion ......................................................................................................9 Suites of Species: Occurrences and Habitat Management ...........................................12 Progress and Next Steps .................................................................................................13 Appendix I: Suites of Species ..........................................................................................17 Florida Panhandle ............................................................................................................................18 Peninsular Florida .............................................................................................................................28 Southern Blue Ridge and Southern Ridge and Valley ...............................................................................................................................39 Interior Low Plateau and Cumberland Plateau, Central Ridge and Valley ...............................................................................................46 -

Freshwater Mollusca of Plummers Island, Maryland Author(S): Timothy A

Freshwater Mollusca of Plummers Island, Maryland Author(s): Timothy A. Pearce and Ryan Evans Source: Bulletin of the Biological Society of Washington, 15(1):20-30. Published By: Biological Society of Washington DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2988/0097-0298(2008)15[20:FMOPIM]2.0.CO;2 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2988/0097-0298%282008%2915%5B20%3AFMOPIM %5D2.0.CO%3B2 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Freshwater Mollusca of Plummers Island, Maryland Timothy A. Pearce and Ryan Evans (TAP) Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Section of Mollusks, 4400 Forbes Avenue, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213, U.S.A., e-mail: [email protected]; (RE) Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program, Pittsburgh Office, 209 Fourth Avenue, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222, U.S.A. Abstract.—We found 19 species of freshwater mollusks (seven bivalves, 12 gastropods) in the Plummers Island area, Maryland, bringing the total known for the Middle Potomac River to 42 species. -

DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Fish

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [Docket No. FWS–R4–ES–2011–0049] [MO 92210-0-0009] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Partial 90-Day Finding on a Petition to List 404 Species in the Southeastern United States as Endangered or Threatened With Critical Habitat AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice of petition finding and initiation of status review. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), announce a partial 90- day finding on a petition to list 404 species in the southeastern United States as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act). Based on our review, we find that for 374 of the 404 species, the petition presents substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that listing may be warranted. 1 Therefore, with the publication of this notice, we are initiating a status review of the 374 species to determine if listing is warranted. To ensure that the review is comprehensive, we are soliciting scientific and commercial information regarding these 374 species. Based on the status reviews, we will issue 12-month findings on the petition, which will address whether the petitioned action is warranted, as provided in section 4(b)(3)(B) of the Act. Of the 30 other species in the petition, 1 species—Alabama shad—has had a 90- day finding published by the National Marine Fisheries Service, and 18 species are already on the Service’s list of candidate species or are presently the subject of proposed rules to list. -

Conservation Status of Freshwater Gastropods of Canada and the United States Paul D

This article was downloaded by: [69.144.7.122] On: 24 July 2013, At: 12:35 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Fisheries Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ufsh20 Conservation Status of Freshwater Gastropods of Canada and the United States Paul D. Johnson a , Arthur E. Bogan b , Kenneth M. Brown c , Noel M. Burkhead d , James R. Cordeiro e o , Jeffrey T. Garner f , Paul D. Hartfield g , Dwayne A. W. Lepitzki h , Gerry L. Mackie i , Eva Pip j , Thomas A. Tarpley k , Jeremy S. Tiemann l , Nathan V. Whelan m & Ellen E. Strong n a Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (ADCNR) , 2200 Highway 175, Marion , AL , 36756-5769 E-mail: b North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences , Raleigh , NC c Louisiana State University , Baton Rouge , LA d United States Geological Survey, Southeast Ecological Science Center , Gainesville , FL e University of Massachusetts at Boston , Boston , Massachusetts f Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources , Florence , AL g U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service , Jackson , MS h Wildlife Systems Research , Banff , Alberta , Canada i University of Guelph, Water Systems Analysts , Guelph , Ontario , Canada j University of Winnipeg , Winnipeg , Manitoba , Canada k Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources , Marion , AL l Illinois Natural History Survey , Champaign , IL m University of Alabama , Tuscaloosa , AL n Smithsonian Institution, Department of Invertebrate Zoology , Washington , DC o Nature-Serve , Boston , MA Published online: 14 Jun 2013. -

A Primer to Freshwater Gastropod Identification

Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society Freshwater Gastropod Identification Workshop “Showing your Shells” A Primer to Freshwater Gastropod Identification Editors Kathryn E. Perez, Stephanie A. Clark and Charles Lydeard University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama 15-18 March 2004 Acknowledgments We must begin by acknowledging Dr. Jack Burch of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan. The vast majority of the information contained within this workbook is directly attributed to his extraordinary contributions in malacology spanning nearly a half century. His exceptional breadth of knowledge of mollusks has enabled him to synthesize and provide priceless volumes of not only freshwater, but terrestrial mollusks, as well. A feat few, if any malacologist could accomplish today. Dr. Burch is also very generous with his time and work. Shell images Shell images unless otherwise noted are drawn primarily from Burch’s forthcoming volume North American Freshwater Snails and are copyright protected (©Society for Experimental & Descriptive Malacology). 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments...........................................................................................................2 Shell images....................................................................................................................2 Table of Contents............................................................................................................3 General anatomy and terms .............................................................................................4 -

American Fisheries Society • JUNE 2013

VOL 38 NO 6 FisheriesAmerican Fisheries Society • www.fisheries.org JUNE 2013 All Things Aquaculture Habitat Connections Hobnobbing Boondoggles? Freshwater Gastropod Status Assessment Effects of Anthropogenic Chemicals 03632415(2013)38(6) Biology and Management of Inland Striped Bass and Hybrid Striped Bass James S. Bulak, Charles C. Coutant, and James A. Rice, editors The book provides a first-ever, comprehensive overview of the biology and management of striped bass and hybrid striped bass in the inland waters of the United States. The book’s 34 chapters are divided into nine major sections: History, Habitat, Growth and Condition, Population and Harvest Evaluation, Stocking Evaluations, Natural Reproduction, Harvest Regulations, Conflicts, and Economics. A concluding chapter discusses challenges and opportunities currently facing these fisheries. This compendium will serve as a single source reference for those who manage or are interested in inland striped bass or hybrid striped bass fisheries. Fishery managers and students will benefit from this up-to-date overview of priority topics and techniques. Serious anglers will benefit from the extensive information on the biology and behavior of these popular sport fishes. 588 pages, index, hardcover List price: $79.00 AFS Member price: $55.00 Item Number: 540.80C Published May 2013 TO ORDER: Online: fisheries.org/ bookstore American Fisheries Society c/o Books International P.O. Box 605 Herndon, VA 20172 Phone: 703-661-1570 Fax: 703-996-1010 Fisheries VOL 38 NO 6 JUNE 2013 Contents COLUMNS President’s Hook 245 Scientific Meetings are Essential If our society considers student participation in our major meetings as a high priority, why are federal and state agen- cies inhibiting attendance by their fisheries professionals at these very same meetings, deeming them non-essential? A colony of the federally threatened Tulotoma attached to the John Boreman—AFS President underside of a small boulder from lower Choccolocco Creek, 262 Talladega County, Alabama. -

Introduction to Mollusca and the Class Gastropoda

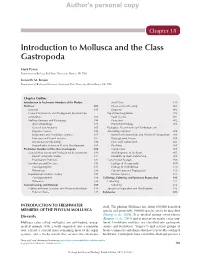

Author's personal copy Chapter 18 Introduction to Mollusca and the Class Gastropoda Mark Pyron Department of Biology, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA Kenneth M. Brown Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA Chapter Outline Introduction to Freshwater Members of the Phylum Snail Diets 399 Mollusca 383 Effects of Snail Feeding 401 Diversity 383 Dispersal 402 General Systematics and Phylogenetic Relationships Population Regulation 402 of Mollusca 384 Food Quality 402 Mollusc Anatomy and Physiology 384 Parasitism 402 Shell Morphology 384 Production Ecology 403 General Soft Anatomy 385 Ecological Determinants of Distribution and Digestive System 386 Assemblage Structure 404 Respiratory and Circulatory Systems 387 Watershed Connections and Chemical Composition 404 Excretory and Neural Systems 387 Biogeographic Factors 404 Environmental Physiology 388 Flow and Hydroperiod 405 Reproductive System and Larval Development 388 Predation 405 Freshwater Members of the Class Gastropoda 388 Competition 405 General Systematics and Phylogenetic Relationships 389 Snail Response to Predators 405 Recent Systematic Studies 391 Flexibility in Shell Architecture 408 Evolutionary Pathways 392 Conservation Ecology 408 Distribution and Diversity 392 Ecology of Pleuroceridae 409 Caenogastropods 393 Ecology of Hydrobiidae 410 Pulmonates 396 Conservation and Propagation 410 Reproduction and Life History 397 Invasive Species 411 Caenogastropoda 398 Collecting, Culturing, and Specimen Preparation 412 Pulmonata 398 Collecting 412 General Ecology and Behavior 399 Culturing 413 Habitat and Food Selection and Effects on Producers 399 Specimen Preparation and Identification 413 Habitat Choice 399 References 413 INTRODUCTION TO FRESHWATER shell. The phylum Mollusca has about 100,000 described MEMBERS OF THE PHYLUM MOLLUSCA species and potentially 100,000 species yet to be described (Strong et al., 2008).