Classification of Real Property Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk

Federal Trade Commission ftc.gov The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk Buying a home can be exciting. It also can be somewhat daunting, even if you’ve done it before. You will deal with mortgage options, credit reports, loan applications, contracts, points, appraisals, change orders, inspections, warranties, walk-throughs, settlement sheets, escrow accounts, recording fees, insurance, taxes...the list goes on. No doubt you will hear and see words and terms you’ve never heard before. Just what do they all mean? The Federal Trade Commission, the agency that promotes competition and protects consumers, has prepared this glossary to help you better understand the terms commonly used in the real estate and mortgage marketplace. A Annual Percentage Rate (APR): The cost of Appraisal: A professional analysis used a loan or other financing as an annual rate. to estimate the value of the property. This The APR includes the interest rate, points, includes examples of sales of similar prop- broker fees and certain other credit charges erties. a borrower is required to pay. Appraiser: A professional who conducts an Annuity: An amount paid yearly or at other analysis of the property, including examples regular intervals, often at a guaranteed of sales of similar properties in order to de- minimum amount. Also, a type of insurance velop an estimate of the value of the prop- policy in which the policy holder makes erty. The analysis is called an “appraisal.” payments for a fixed period or until a stated age, and then receives annuity payments Appreciation: An increase in the market from the insurance company. -

Number 27 of 1965 SUCCESSION ACT 1965 REVISED Updated to 4

Number 27 of 1965 SUCCESSION ACT 1965 REVISED Updated to 4 May 2020 This Revised Act is an administrative consolidation of the Succession Act 1965. It is prepared by the Law Reform Commission in accordance with its function under the Law Reform Commission Act 1975 (3/1975) to keep the law under review and to undertake revision and consolidation of statute law. All Acts up to and including the Emergency Measures in the Public Interest (Covid-19) Act 2020 (2/2020), enacted 27 March 2020 and all statutory instruments up to and including the Planning and Development Act 2000 (Subsection (4) of Section 251A) (No. 2) Order 2020 (S.I. No. 165 of 2020), made 8 May 2020, were considered in the preparation of this Revised Act. Disclaimer: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this Revised Act, the Law Reform Commission can assume no responsibility for and give no guarantees, undertakings or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or up to date nature of the information provided and does not accept any liability whatsoever arising from any errors or omissions. Please notify any errors, omissions and comments by email to [email protected]. Number 27 of 1965 SUCCESSION ACT 1965 REVISED Updated to 4 May 2020 Introduction This Revised Act presents the text of the Act as it has been amended since enactment, and preserves the format in which it was passed. Related legislation This Act is not collectively cited with any other Act. Annotations This Revised Act is annotated and includes textual and non-textual amendments, statutory instruments made pursuant to the Act and previous affecting provisions. -

Convey 04 Eug. Amend 06 Aug. Final

LAW SOCIETY CONVEYANCING HANDBOOK CHAPTER 4 LANDLORD AND TENANT LEASES OF meeting of the solicitors acting for Lending Institutions in Dublin has considered the DWELLINGHOUSES Aeffect of Section 2 of the Landlord and Tenant (Ground Rents) (No. 1) Bill 1977, having regard to the practice of leases of dwellinghouses on building estates being executed 1978 (NO.1) ACT by all parties well in advance of the completion of the houses, and being held in escrow by the lessor’s solicitors, usually to enable stamp duty on the lease to be assessed and impressed prior to completion. It was the unanimous view of the solicitors present that such a lease even though dated prior to the date of coming into force of the Act would be void under the Act if it were held in escrow at the date of the passing of the Act and then delivered to the purchasers afterwards. The meeting further considered the difficulties which would face a Lending Institution’s solicitor presented, shortly after the passing of the Act, with a lease dated prior to the date of passing of the Act, of deciding whether such a lease were void because it had been held in escrow or valid because it had been delivered prior to the passing of the Act. The view of the meeting was that a Lending Institution solicitor could not undertake the burden of making such a decision. The meeting noted that the provisions of Section 2, Sub-section (4) of the Bill which protected the position of a purchaser of a leasehold interest deemed void under Section 2, Sub-section (1), did not extend to a mortgagee and accordingly agreed that the solicitors acting for Lending Institutions would not be able to accept leases of dwellinghouses after the date of coming into force of the Act even though the leases might have been dated prior to the passing of the Act. -

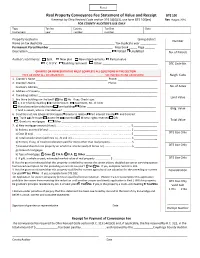

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt DTE 100 If exempt by Ohio Revised Code section 319.54(G)(3), use form DTE 100(ex) Rev 1/14 FOR COUNTY AUDITOR’S USE ONLY Type Tax list County Tax Dist Date Instrument year number number Property located in ____________________________________________________________ taxing district Number Name on tax duplicate ____________________________________________ Tax duplicate year __________ Permanent Parcel Number _______________________________________ Map book _____ Page ______ Description ___________________________________________________ Platted Unplatted No. of Parcels Auditor’s comments: Split New plat New improvements Partial value C.A.U.V. Building removed Other __________________________________ DTE Code No. GRANTEE OR REPRESENTATIVE MUST COMPLETE ALL QUESTIONS IN THIS SECTION TYPE OR PRINT ALL INFORMATION SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON REVERSE Neigh. Code 1. Grantor’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ 2. Grantee’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ Grantee’s Address__________________________________________________________________________________ No. of Acres 3. Address of Property ________________________________________________________________________________ 4. Tax billing address _________________________________________________________________________________ Land Value 5. Are there buildings on the land? Yes No If yes, Check type: 1, 2 or 3 family dwelling Condominium -

Conveyancing and the Law of Real Property

September 2014 - ISSUE 19 Conveyancing and The Law of Real Property The questions may be asked what is Conveyancing and why is Property Rules and his first act must be to undertake an inves‐ it attached to the Law of Real Property. tigation into the title of the Vendor’s property. This search which must be conducted in the Register of Deeds and should When dealing with the Law of Real Property there are two involve a period of time of thirty years or longer in the case fundamental points which must be understood‐‐‐ where the date of the Vendor’s Deed is older than thirty years. (i) You acquire knowledge of the rights and liabilities attached to the interests of the owner in the land and The Cause List search is undertaken in the Supreme Court Registry and the purpose of which is to ascertain whether (ii) The foundation of the Rules of Conveyancing. there are any liens pending against the Vendor in the Su‐ preme Court Register. If there are pending liens, they must be It is not easy to distinguish accurately between Real Property settled by the Vendor before he is able to sell the property. and Conveyancing. It is said that Real Property deals with the rights and liabilities of land owners. Conveyancing on the The original documents of title must be produced by the Ven‐ other hand is the art of creating and transferring rights in land dor and delivered to the attorney for review. I the Vendor is and thus the Rules of Conveyancing and the Law of Real Prop‐ unable to produce the same and the attorney has found the erty cannot be distinguished as separate subjects though re‐ title to be good and marketable, then the Vendor must sign lated closely but should be distinguished as two parts of one and swear an Affidavit of Loss in respect of such lost or mis‐ subject of land law. -

Real & Personal Property

CHAPTER 5 Real Property and Personal Property CHRIS MARES (Appleton, Wsconsn) hen you describe property in legal terms, there are two types of property. The two types of property Ware known as real property and personal property. Real property is generally described as land and buildings. These are things that are immovable. You are not able to just pick them up and take them with you as you travel. The definition of real property includes the land, improvements on the land, the surface, whatever is beneath the surface, and the area above the surface. Improvements are such things as buildings, houses, and structures. These are more permanent things. The surface includes landscape, shrubs, trees, and plantings. Whatever is beneath the surface includes the soil, along with any minerals, oil, gas, and gold that may be in the soil. The area above the surface is the air and sky above the land. In short, the definition of real property includes the earth, sky, and the structures upon the land. In addition, real property includes ownership or rights you may have for easements and right-of-ways. This may be for a driveway shared between you and your neighbor. It may be the right to travel over a part of another person’s land to get to your property. Another example may be where you and your neighbor share a well to provide water to each of your individual homes. Your real property has a formal title which represents and reflects your ownership of the real property. The title ownership may be in the form of a warranty deed, quit claim deed, title insurance policy, or an abstract of title. -

Real Property Conveyance Fee

Real Property Conveyance Fee tate law establishes a mandatory conveyance fee that is exempt from federal income taxation, when on the transfer of real property. The fee is calculated the transfer is without consideration and furthers the Sbased on a percentage of the property value that is agency’s charitable or public purpose. transferred. In addition to the mandatory fee, all but one • when property is sold to provide or release security county levies a permissive real property transfer fee. The for a debt, or for delinquent taxes, or pursuant to a revenue from both the mandatory fee and the permissive court order. fee is deposited in the general fund of the county in which • when a corporation transfers property to a stock the property is located - no revenue goes to the state. In holder in exchange for their shares during a corporate 2013, the latest year for which data is available, convey reorganization or dissolution. ance fees generated approximately $108.7 million in rev • when property is transferred by lease, unless the enues to counties: $34.0 million from mandatory fees and lease is for a term of years renewable forever. $74.7 million from permissive fees. • to a grantee other than a dealer, solely for the pur pose of, and as a step in, the prompt sale to others. Taxpayer • to sales or transfers to or from a person when no (Ohio Revised Code 319.202 and 322.06) money or other valuable and tangible consideration The real property conveyance fee is paid by persons readily convertible into money is paid or is to be paid who make sales of real estate or used manufactured for the realty, and the transaction is not a gift. -

Condominium Ownership of Real Property

CHAPTER 47-04.1 CONDOMINIUM OWNERSHIP OF REAL PROPERTY 47-04.1-01. Definitions. In this chapter, unless context otherwise requires: 1. "Common areas" means the entire project excepting all units therein granted or reserved. 2. "Condominium" is an estate in real property consisting of an undivided interest or interests in common in a portion of a parcel of real property together with a separate interest or interests in space in a structure, on such real property. 3. "Interest" means the fractional or percentage interest or interests ascribed to each unit by the declaration provided for in section 47-04.1-03. 4. "Limited common areas" means those elements designed for use by the owners of one or more but less than all of the units included in the project. 5. "Project" means the entire parcel of real property divided, or to be divided into condominiums, including all structures thereon. 6. "To divide" real property means to divide the ownership thereof by conveying one or more condominiums therein but less than the whole thereof. 7. "Unit" means the elements of a condominium which are not owned in common with the owners of other condominiums in the project. 47-04.1-02. Recording of declaration to submit property to a project. When the sole owner or all the owners, or the sole lessee or all of the lessees of a lease desire to submit a parcel of real property to a project established by this chapter, a declaration to that effect shall be executed and acknowledged by the sole owner or lessee or all of such owners or lessees and shall be recorded in the office of the recorder of the county in which such property lies. -

41.01.01 Real Property

41.01.01 Real Property Revised September 21, 2021 Next Scheduled Review: September 21, 2026 Click to view Revision History. Regulation Summary This regulation provides uniform guidance for the acquisition, disposition, lease and license of real property and delegates authority to the chief executive officers (CEO) or designees of The Texas A&M University System (system). Definitions Click to view Definitions. Regulation 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS 1.1 System Real Estate Office. Except as otherwise provided in this regulation, all activities involving the acquisition, disposition, lease and license of a surface estate, except those activities and operations commonly associated with easements and right-of-ways, will be consolidated in the System Real Estate Office (SREO) and coordinated with the appropriate member or members. 1.2 System Energy Resource Office. Except as otherwise provided in this regulation, all activities involving the acquisition, disposition and lease of a mineral estate, and those activities commonly associated with easements and right-of-ways of a surface estate, will be consolidated in the System Energy Resource Office (SERO) and coordinated with the appropriate member or members. 1.3 Intrasystem Assignment of Real Property. Subject to any legal requirements or donor restrictions, real property used primarily for member purposes will be assigned to the using member for maintenance, operation and management purposes. Real property may be reassigned by the chancellor based on the primary use or proposed use of the property. The reassignment will be evidenced by a form prepared by SREO, signed by the chancellor and maintained by SREO. 1.4 Maintenance of Inventory and Records. -

The Relationship Between Property Rights and Civil Rights Richard R

Hastings Law Journal Volume 15 | Issue 2 Article 3 1-1963 The Relationship between Property Rights and Civil Rights Richard R. B. Powell Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard R. B. Powell, The Relationship between Property Rights and Civil Rights, 15 Hastings L.J. 135 (1963). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol15/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. The Relationship Between Property Rights and Civil Rights By RICHARD R. B. POWELL LAW has, as a major function, the lubrication of the mechanisms of society. It is its task to afford people, in the accelerated closeness of modern living, a society in which they are able to live together harmoni- ously and with mutual advantage. On this approach it is not far-fetched to say that the most important internal problem of the United States in 1963 is the treatment of its minorities. This problem has generated more heat, more human hostility, more evidence of the need for better lubri- cation than any other single aspect of current society. Can "law" do a better job? If so, how? It is always easier to tell other people, living at a distance, how they can improve their behavior and their law. But, perhaps, it is more profitable to start with the behavior and the law in the community wherein we sleep. -

Real Estate 2019

ICLG The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Real Estate 2019 14th Edition A practical cross-border insight into real estate law Published by Global Legal Group with contributions from: ALTIUS Maples and Calder Anderson Mori & Tomotsune Marval, O’Farrell & Mairal Blenheim Meyerlustenberger Lachenal AG Brulc, Gaberščik and partners, Law Firm, Ltd. Norton Rose Fulbright South Africa Inc. Cordero & Cordero Abogados Pepeliaev Group Eric Silwamba, Jalasi and Linyama Legal Practitioners Project Law Attorneys Ltd Ferraiuoli LLC Ropes & Gray International LLP Gianni, Origoni, Grippo, Cappelli & Partners Shepherd and Wedderburn LLP Greenberg Traurig Grzesiak sp.k. Simon Reid-Kay & Associates Greenberg Traurig, LLP Taras Burhan Law Office LLC Hogan Lovells Tirard, Naudin Kapellmann Tughan Kubes Passeyrer Attorneys at Law Valmas Associates L&L Partners Wintertons Legal Practitioners Machado, Meyer, Sendacz e Opice Advogados Ziv Lev & Co. Law Office Mantis & Athinodorou LLC The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Real Estate 2019 General Chapter: 1 Forward Funding Now! – Iain Morpeth, Ropes & Gray LLP 1 Country Question and Answer Chapters: 2 Argentina Marval, O’Farrell & Mairal: Diego A. Chighizola 5 Contributing Editor Iain Morpeth, 3 Austria Kubes Passeyrer Attorneys at Law: Dr. David Kubes & Mag. Tina Vollmann 17 Ropes & Gray LLP 4 ALTIUS: Lieven Peeters & Kathleen Verbiest 27 Sales Director Belgium Florjan Osmani 5 Brazil Machado, Meyer, Sendacz e Opice Advogados: Maria Flavia Seabra & Account Director Juliana Ribeiro 36 Oliver Smith 6 Costa Rica Cordero & Cordero Abogados: Hernan Cordero B. & Rolando Gonzalez C. 45 Sales Support Manager Toni Hayward 7 Cyprus Mantis & Athinodorou LLC: Michael Mantis 55 Senior Editors 8 England & Wales Ropes & Gray International LLP: Carol Hopper & Partha Pal 63 Caroline Collingwood & Suzie Levy 9 Finland Project Law Attorneys Ltd: Matias Forss & Sakari Lähteenmäki 75 CEO Dror Levy 10 France Tirard, Naudin: Maryse Naudin 83 Group Consulting Editor 11 Germany Kapellmann: Dr. -

Introduction to Will Drafting for Accountants

Introduction to Will Drafting for Accountants MONDAY, 25 MARCH 2019 In association with… icaew.com The value of ICAEW membership Qualified professionals to advise you on technical and 1 ethical matters 259 World class Industry and library ... country guides ... with Connecting information ACA/FCA members through and research online professionals communities, offering blogs and forums tailored help Internationally recognised designatory letters Member App available on Android and iOS INTELLIGENCE AND INSIGHT APRIL 2015 | ICAEW.COM/ECONOMIA ISSUE 37 | ACCOUNTANCY | FINANCE | BUSINESS 200+ Confidential Fight for and non- your right Specialist technical Multimillionaire barrow boy Barry Hearn on fortune, family and making his own way helpsheets and judgmental PRIVATE EQUITY THE PENSIONS REVOLUTION EUROPEAN support and ROAD TRIPS FAQs advice 18 International member groups 3,450+ 24h electronic 24 10 journals UK District International Societies offices and books Information online when you need it – no cost, no time zone, no delay Agenda Time Session 09:00 Registration 09:30 Formal requirement for wills; When to use life interest trusts; When to use discretionary trusts; Taking instructions for a will – who is the client?, family, size of estate, who does the client wish to benefit; Capacity to make a will and knowledge and approval of the contents; Undue influence: Conflict of interest – couples may have different wishes; Does client have an equitable interest in a house vested in the name of someone else? Does someone else have an equitable