Texas Private Real Property Rights Preservation Act Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Intellectual Property Law

ee--RRGG Electronic Resource Guide International Intellectual Property Law * Jonathan Franklin This page was last updated February 8, 2013. his electronic resource guide, often called the ERG, has been published online by the American Society of International Law (ASIL) since 1997. T Since then it has been systematically updated and continuously expanded. The chapter format of the ERG is designed to be used by students, teachers, practitioners and researchers as a self-guided tour of relevant, quality, up-to-date online resources covering important areas of international law. The ERG also serves as a ready-made teaching tool at graduate and undergraduate levels. The narrative format of the ERG is complemented and augmented by EISIL (Electronic Information System for International Law), a free online database that organizes and provides links to, and useful information on, web resources from the full spectrum of international law. EISIL's subject-organized format and expert-provided content also enhances its potential as teaching tool. 2 This page was last updated February 8, 2013. I. Introduction II. Overview III. Research Guides and Bibliographies a. International Intellectual Property Law b. International Patent Law i. Public Health and IP ii. Agriculture, Plant Varieties, and IP c. International Copyright Law i. Art, Cultural Property, and IP d. International Trademark Law e. Trade and IP f. Arbitration, Mediation, and IP g. Traditional Knowledge and IP h. Geographical Indications IV. General Search Strategies V. Primary Sources VI. Primary National Legislation and Decisions VII. Recommended Link sites VIII. Selected Non-Governmental Organizations IX. Electronic Current Awareness 3 This page was last updated February 8, 2013. -

The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk

Federal Trade Commission ftc.gov The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk Buying a home can be exciting. It also can be somewhat daunting, even if you’ve done it before. You will deal with mortgage options, credit reports, loan applications, contracts, points, appraisals, change orders, inspections, warranties, walk-throughs, settlement sheets, escrow accounts, recording fees, insurance, taxes...the list goes on. No doubt you will hear and see words and terms you’ve never heard before. Just what do they all mean? The Federal Trade Commission, the agency that promotes competition and protects consumers, has prepared this glossary to help you better understand the terms commonly used in the real estate and mortgage marketplace. A Annual Percentage Rate (APR): The cost of Appraisal: A professional analysis used a loan or other financing as an annual rate. to estimate the value of the property. This The APR includes the interest rate, points, includes examples of sales of similar prop- broker fees and certain other credit charges erties. a borrower is required to pay. Appraiser: A professional who conducts an Annuity: An amount paid yearly or at other analysis of the property, including examples regular intervals, often at a guaranteed of sales of similar properties in order to de- minimum amount. Also, a type of insurance velop an estimate of the value of the prop- policy in which the policy holder makes erty. The analysis is called an “appraisal.” payments for a fixed period or until a stated age, and then receives annuity payments Appreciation: An increase in the market from the insurance company. -

U-I-313/13-91 27 March 2014 Concurring Opinion of Judge Jan

U-I-313/13-91 27 March 2014 Concurring Opinion of Judge Jan Zobec 1. Although I voted for the Decision in its entirety and also concur to a certain degree with its underlying reasons, I wish to express, in my concurring opinion, my view on property taxes from the viewpoint of the constitutional guarantee of private property, especially the private property of residential real property. The applicants namely also referred to the fact that the real property tax excessively interferes with the constitutional guarantee of private property, and the Decision does not contain answers to these allegations. A few brief introductory thoughts on the importance of private property in the circle of civilisation to which we belong 2. Private property entails one of the central constitutional values and one of the pillars of western civilisation. Already the Magna Carta Libertatum or The Great Charter of the Liberties of England of 1215, which made the king's power subject to law and which entails the first step towards the implementation of the idea of the rule of law, contained numerous important safeguards of ownership – e.g. the principle that in order to increase the budget of the state it is necessary to obtain the approval of the representative body; the provision that the crown's officials must not seize anyone's movable property without immediate payment – unless the seller voluntarily agrees that the payment be postponed; it also ensured protection from unlawful deprivation of possession or (arbitrary) deprivation without a judicial decision.[1] The theory on property rights also occupies the central position in the political philosophy of John Locke, which inspired the American Revolution and was reflected in the Declaration of Independence. -

Property Crime

Uniform Crime Report Crime in the United States, 2010 Property Crime Definition In the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program, property crime includes the offenses of burglary, larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson. The object of the theft-type offenses is the taking of money or property, but there is no force or threat of force against the victims. The property crime category includes arson because the offense involves the destruction of property; however, arson victims may be subjected to force. Because of limited participation and varying collection procedures by local law enforcement agencies, only limited data are available for arson. Arson statistics are included in trend, clearance, and arrest tables throughout Crime in the United States, but they are not included in any estimated volume data. The arson section in this report provides more information on that offense. Data collection The data presented in Crime in the United States reflect the Hierarchy Rule, which requires that only the most serious offense in a multiple-offense criminal incident be counted. In descending order of severity, the violent crimes are murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault, followed by the property crimes of burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft. Although arson is also a property crime, the Hierarchy Rule does not apply to the offense of arson. In cases in which an arson occurs in conjunction with another violent or property crime, both crimes are reported, the arson and the additional crime. Overview • In 2010, there were an estimated 9,082,887 property crime offenses in the Nation. -

Aristotle's Economic Defence of Private Property

ECONOMIC HISTORY ARISTOTLE ’S ECONOMIC DEFENCE OF PRIVATE PROPERTY CONOR MCGLYNN Senior Sophister Are modern economic justifications of private property compatible with Aristotle’s views? Conor McGlynn deftly argues that despite differences, there is much common ground between Aristotle’s account and contemporary economic conceptions of private property. The paper explores the concepts of natural exchange and the tragedy of the commons in order to reconcile these divergent views. Introduction Property rights play a fundamental role in the structure of any economy. One of the first comprehensive defences of the private ownership of property was given by Aristotle. Aris - totle’s defence of private property rights, based on the role private property plays in pro - moting virtue, is often seen as incompatible with contemporary economic justifications of property, which are instead based on mostly utilitarian concerns dealing with efficiency. Aristotle defends private ownership only insofar as it plays a role in promoting virtue, while modern defenders appeal ultimately to the efficiency gains from private property. However, in spite of these fundamentally divergent views, there are a number of similar - ities between the defence of private property Aristotle gives and the account of private property provided by contemporary economics. I will argue that there is in fact a great deal of overlap between Aristotle’s account and the economic justification. While it is true that Aristotle’s theory is quite incompatible with a free market libertarian account of pri - vate property which defends the absolute and inalienable right of an individual to their property, his account is compatible with more moderate political and economic theories of private property. -

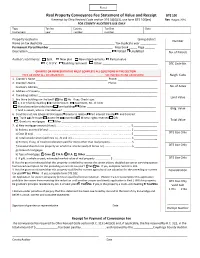

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt DTE 100 If exempt by Ohio Revised Code section 319.54(G)(3), use form DTE 100(ex) Rev 1/14 FOR COUNTY AUDITOR’S USE ONLY Type Tax list County Tax Dist Date Instrument year number number Property located in ____________________________________________________________ taxing district Number Name on tax duplicate ____________________________________________ Tax duplicate year __________ Permanent Parcel Number _______________________________________ Map book _____ Page ______ Description ___________________________________________________ Platted Unplatted No. of Parcels Auditor’s comments: Split New plat New improvements Partial value C.A.U.V. Building removed Other __________________________________ DTE Code No. GRANTEE OR REPRESENTATIVE MUST COMPLETE ALL QUESTIONS IN THIS SECTION TYPE OR PRINT ALL INFORMATION SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON REVERSE Neigh. Code 1. Grantor’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ 2. Grantee’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ Grantee’s Address__________________________________________________________________________________ No. of Acres 3. Address of Property ________________________________________________________________________________ 4. Tax billing address _________________________________________________________________________________ Land Value 5. Are there buildings on the land? Yes No If yes, Check type: 1, 2 or 3 family dwelling Condominium -

Exclusivity and the Construction of Intellectual Property Markets

The Fable of the Commons: Exclusivity and the Construction of Intellectual Property Markets Shubha Ghosh* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 857 I. LOOKING BEYOND THE COMMONS: TURNING HIGH TRAGEDY INTO LOW DRAMA .................................................................... 860 A. The Fable of the Commons................................................. 861 B. Governing the Commons Through the Goals of Distributive Justice ............................................................ 864 II. THE DIMENSIONS OF DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE.............................. 870 A. Creators ............................................................................ 871 B. Creators and Users............................................................ 876 C. Intergenerational Justice.................................................... 879 III. DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE IN PRACTICE .......................................... 880 A. Fair Use: Allocating Surplus Among Creators and Users .. 881 B. Secondary Liability: Spanning Generational Divides......... 883 C. Antitrust: Natural and Cultural Monopolies and the Limits of Exclusivity in the Marketplace ............................ 886 D. Traditional Knowledge: Expanding Canons and the Global Marketplace ........................................................... 888 CONCLUSION....................................................................................... 889 * Professor of Law, Southern Methodist University, Dedman School -

Conveyancing and the Law of Real Property

September 2014 - ISSUE 19 Conveyancing and The Law of Real Property The questions may be asked what is Conveyancing and why is Property Rules and his first act must be to undertake an inves‐ it attached to the Law of Real Property. tigation into the title of the Vendor’s property. This search which must be conducted in the Register of Deeds and should When dealing with the Law of Real Property there are two involve a period of time of thirty years or longer in the case fundamental points which must be understood‐‐‐ where the date of the Vendor’s Deed is older than thirty years. (i) You acquire knowledge of the rights and liabilities attached to the interests of the owner in the land and The Cause List search is undertaken in the Supreme Court Registry and the purpose of which is to ascertain whether (ii) The foundation of the Rules of Conveyancing. there are any liens pending against the Vendor in the Su‐ preme Court Register. If there are pending liens, they must be It is not easy to distinguish accurately between Real Property settled by the Vendor before he is able to sell the property. and Conveyancing. It is said that Real Property deals with the rights and liabilities of land owners. Conveyancing on the The original documents of title must be produced by the Ven‐ other hand is the art of creating and transferring rights in land dor and delivered to the attorney for review. I the Vendor is and thus the Rules of Conveyancing and the Law of Real Prop‐ unable to produce the same and the attorney has found the erty cannot be distinguished as separate subjects though re‐ title to be good and marketable, then the Vendor must sign lated closely but should be distinguished as two parts of one and swear an Affidavit of Loss in respect of such lost or mis‐ subject of land law. -

Real & Personal Property

CHAPTER 5 Real Property and Personal Property CHRIS MARES (Appleton, Wsconsn) hen you describe property in legal terms, there are two types of property. The two types of property Ware known as real property and personal property. Real property is generally described as land and buildings. These are things that are immovable. You are not able to just pick them up and take them with you as you travel. The definition of real property includes the land, improvements on the land, the surface, whatever is beneath the surface, and the area above the surface. Improvements are such things as buildings, houses, and structures. These are more permanent things. The surface includes landscape, shrubs, trees, and plantings. Whatever is beneath the surface includes the soil, along with any minerals, oil, gas, and gold that may be in the soil. The area above the surface is the air and sky above the land. In short, the definition of real property includes the earth, sky, and the structures upon the land. In addition, real property includes ownership or rights you may have for easements and right-of-ways. This may be for a driveway shared between you and your neighbor. It may be the right to travel over a part of another person’s land to get to your property. Another example may be where you and your neighbor share a well to provide water to each of your individual homes. Your real property has a formal title which represents and reflects your ownership of the real property. The title ownership may be in the form of a warranty deed, quit claim deed, title insurance policy, or an abstract of title. -

Private Property Rights, Economic Freedom, and Well Being

Working Paper 19 Private Property Rights, Economic Freedom, and Well Being * BENJAMIN POWELL * Benjamin Powell is a PhD Student at George Mason University and a Social Change Research Fellow with the Mercatus Center in Arlington, VA. He was an AIER Summer Fellow in 2002. The ideas presented in this research are the author’s and do not represent official positions of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Private Property Rights, Economic Freedom, and Well Being The question of why some countries are rich, and others are poor, is a question that has plagued economists at least since 1776, when Adam Smith wrote An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Some countries that have a wealth of human and natural resources remain in poverty (in Sub-Saharan Africa for example) while other countries with few natural resources (like Hong Kong) flourish. An understanding of how private property and economic freedom allow people to coordinate their activities while engaging in trades that make them both people better off, gives us an indication of the institutional environment that is necessary for prosperity. Observation of the countries around the world also indicates that those countries with an institutional environment of secure property rights and highPAPER degrees of economic freedom have achieved higher levels of the various measures of human well being. Property Rights and Voluntary Interaction The freedom to exchange allows individuals to make trades that both parties believe will make them better off. Private property provides the incentives for individuals to economize on resource use because the user bears the costs of their actions. -

Property and Ownership

Property and Ownership Gerald Gaus 1 PRIVATE PROPERTY: FUNDAMENTAL OR PASSÉ? For the last half century, thinking within political philosophy about private property and ownership has had something of a schizophrenic quality. The classical liberal tradition has always stressed an intimate connection between a free society and the right to private property.1 As Ludwig von Mises put it, “the program of liberalism....if condensed to a single word, would have to read: property, that is, private ownership....”2 Robert Nozick’s Anarchy, State and Utopia, drawing extensively on Locke, gave new life to this idea; subsequently a great deal of political philosophy has focused on the justification (or lack of it) of natural rights to private property.3 Classical liberals such as Eric Mack — also drawing extensively on Locke’s theory of property — have argued that “the signature right of any rights-oriented classical liberalism is the right of self-ownership.”4 In addition, Mack argues that “we have the same good reasons for ascribing to each person a natural right of property” in “extrapersonal objects.”5 Each individual, Mack contends, has “an original, nonacquired right … to engage in the acquisition of extrapersonal objects and in the disposition of those acquired objects as one sees fit in the service of one’s ends.”6 Essentially, one has a natural right to become an owner of external property. Not all contemporary classical liberals hold that property rights are natural, but all insist that strong rights to private property are essential for a free society.7 Jan Narveson has recently defended the necessity in a free society of property understood as “a unitary concept, explicable as a right over a thing owned, against others who are precluded from the free use of it to which ownership entitles the owner.”8 GAUS/2 The “new liberal” project of showing that a free society requires robust protection of civil and political rights, but not extensive rights of private property (beyond personal property) has persistently attacked this older, classical, liberal position. -

Making Room in the Property Canon

Making Room in the Property Canon INTEGRATING SPACES: PROPERTY LAW AND RACE. By Alfred Brophy, Alberto Lopez & Kali Murray. New York, New York: Aspen Publishers, 2011. 368 pages. $40.00. Reviewed by Bela August Walker* I. Introduction Property is oft considered the province of the antediluvian, far situated from modern concerns, particularly issues of race and diversity. Even more so than other areas of legal academia, Property remains the province of dead white men. Courses and casebooks continue to hark back to Blackstone, the epitome of the antiquated.1 The thread of old English law continues throughout the semester, to the consternation of many a first-year law student. It should come as no surprise that Property is then viewed as lifeless, the course least accessible, least relevant, most obscure. Nonetheless, Blackstone once avowed, “There is nothing which so generally strikes the imagination, and engages the affections of mankind, as the right of property . .”2 This adage may prove still true. If property is dead,3 long live Property!4 Integrating Spaces: Property Law and Race takes on one aspect of this potential impasse. Alfred Brophy, Alberto Lopez, and Kali Murray address a long-standing absence and bring the Property casebook into the twenty-first * Associate Professor, Roger Williams University School of Law. For their sage advice and discerning counsel, I am indebted to M.J. Durkee, Sheila Foster, Jack Greenberg, Tanya Hernandez, Sonia Katyal, Jennifer Flynn Walker, and Patricia Williams. 1. Even Integrating Spaces cannot resist beginning its tale with the Englishman’s “‘despotic’ dominion.” ALFRED BROPHY, ALBERTO LOPEZ & KALI MURRAY, INTEGRATING SPACES: PROPERTY LAW AND RACE 3 (2011) [hereinafter INTEGRATING SPACES].