The Donbas Conflict Opposing Interests and Narratives, Difficult Peace Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine 16 May to 15 August 2018

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 May to 15 August 2018 Contents Page I. Executive summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 II. OHCHR methodology ...................................................................................................................... 3 III. Impact of hostilities .......................................................................................................................... 3 A. Conduct of hostilities and civilian casualties ............................................................................. 3 B. Situation at the contact line and rights of conflict-affected persons ............................................ 7 1. Right to restitution and compensation for use or damage of private property ..................... 7 2. Right to social security and social protection .................................................................... 9 3. Freedom of movement, isolated communities and access to basic services ...................... 10 IV. Right to physical integrity ............................................................................................................... 11 A. Access to detainees and places of detention ............................................................................ 11 B. Arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance and abduction, torture and ill-treatment ............... 12 C. Situation -

OPERATION NEMTSOV”: 307 Disinformation, Confusion MARCH and Some Worrying Hypotheses 2015

Centro de Estudios y Documentación InternacionalesCentro de Barcelona E-ISSN 2014-0843 D.L.: B-8438-2012 opiniónEuropa “OPERATION NEMTSOV”: 307 Disinformation, confusion MARCH and some worrying hypotheses 2015 Nicolás de Pedro, Research Fellow, CIDOB Marta Ter, Head of the North Caucasus department at the Lliga dels Drets dels Pobles he investigation into the assassination of Boris Nemtsov reminds previ- ous ones on high-profile political killings, although the uncertainties grow with every new revelation. The verified, documented connec- Ttion between the main suspect, Zaur Dadayev, and Ramzan Kadyrov, Chechen strongman and close ally of Putin strengthens the theory linking the crime to the Kremlin and suggests possible internal fighting within the state security apparatus. Nemtsov joins a long list of critics and opponents who have been assassinated in the last fifteen years. Among the most prominent are:Sergey Yushenkov, member of parliament for the Liberal Russia party (assassinated on April 17th, 2003); Yuri Shchekochikhin, journalist on the Novaya Gazeta (July 3rd, 2003); Paul Klebnikov, US journalist of Russian origin and editor of the Russian edition of Forbes (July 9th, 2004); Anna Politkovskaya, journalist for Novaya Gazeta (October 7th, 2006); Alexander Litvinenko, former KGB/FSB agent (November 23rd, 2006); and Na- talya Estemirova, human rights activist for the Chechen branch of the NGO Me- morial (July 15th, 2009). Each of these assassinations has its own particularities, but none has been properly explained and all of the victims were people who dis- comfited the Kremlin. Despite this, political motivations and possible connections with state apparatus are the only lines of investigation that have been systemati- cally ignored or explicitly denied in all of these cases. -

Statement by the Delegation of Ukraine at the 777-Th FSC Plenary Meeting (28 January 2015 at 10.00, Hofburg)

FSC.DEL/11/15 28 January 2015 ENGLISH only Statement by the Delegation of Ukraine at the 777-th FSC Plenary Meeting (28 January 2015 at 10.00, Hofburg) Mr. Chairman, The Russian aggression against Ukraine, which resulted in illegal occupation and annexation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, as well as escalation in Ukraine’s east, continues and produces a sharply growing number of casualties among civilians and servicemen in Ukraine. On 24 January, Russian‐backed terrorists committed another heinous crime. The deliberate shelling by Grad missiles of the residential areas of the city of Mariupol, followed a number of earlier terrorist attacks, among them the shellings of the civilian bus near Volnovakha, of the trolleybus stop in Donetsk, of residential areas in many towns and villages. The OSCE Special Monitoring Mission’s assessment concluded that the attack had been carried out through the use of Grad and Uragan rockets fired from areas controlled by the “Donetsk People’s Republic”. On January 25, the Ukrainian government reported that the toll from the attack had reached 30 dead and 102 wounded. The Ukrainian Security Service collected evidence, including telephone intercepts and the account of the accomplice of this murderous act, that the artillery attack on peaceful Mariupol was committed by the Russian artillery battery commanded by a Russian officer with a call sign "Pepel". Mr. Chairman, Distinguished colleagues, The cold‐blooded murder of 30 civilians and wounding of more than a hundred people by pro‐Russian terrorists in Mariupol is a crime against humanity. The Ukrainian authorities will do all in their power to make sure that the perpetrators of this heinous crime are brought to justice. -

Minsk II a Fragile Ceasefire

Briefing 16 July 2015 Ukraine: Follow-up of Minsk II A fragile ceasefire SUMMARY Four months after leaders from France, Germany, Ukraine and Russia reached a 13-point 'Package of measures for the implementation of the Minsk agreements' ('Minsk II') on 12 February 2015, the ceasefire is crumbling. The pressure on Kyiv to contribute to a de-escalation and comply with Minsk II continues to grow. While Moscow still denies accusations that there are Russian soldiers in eastern Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin publicly admitted in March 2015 to having invaded Crimea. There is mounting evidence that Moscow continues to play an active military role in eastern Ukraine. The multidimensional conflict is eroding the country's stability on all fronts. While the situation on both the military and the economic front is acute, the country is under pressure to conduct wide-reaching reforms to meet its international obligations. In addition, Russia is challenging Ukraine's identity as a sovereign nation state with a wide range of disinformation tools. Against this backdrop, the international community and the EU are under increasing pressure to react. In the following pages, the current status of the Minsk II agreement is assessed and other recent key developments in Ukraine and beyond examined. This briefing brings up to date that of 16 March 2015, 'Ukraine after Minsk II: the next level – Hybrid responses to hybrid threats?'. In this briefing: • Minsk II – still standing on the ground? • Security-related implications of the crisis • Russian disinformation -

Peacekeepers in the Donbas JFQ 91, 4Th Quarter 2017 12 India to Lead the Mission

Eastern Ukrainian woman, one of over 1 million internally displaced persons due to conflict, has just returned from her destroyed home holding all her possessions, on main street in Nikishino Village, March 1, 2015 (© UNHCR/Andrew McConnell) cal ploy; they have suggested calling Putin’s bluff. However, they also realize Peacekeepers the idea of a properly structured force with a clear mandate operating in support of an accepted peace agreement in the Donbas could offer a viable path to peace that is worth exploring.2 By Michael P. Wagner Putin envisions a limited deploy- ment of peacekeepers on the existing line of contact in Donbas to safeguard OSCE-SMM personnel.3 Such a plan ince the conflict in Ukraine September 5, 2017, when he proposed could be effective in ending the conflict began in 2014, over 10,000 introducing peacekeepers into Eastern and relieving immediate suffering, but it people have died in the fighting Ukraine to protect the Organiza- S could also lead to an open-ended United between Russian-backed separatists tion for Security and Co-operation in Nations (UN) commitment and make and Ukrainian forces in the Donbas Europe–Special Monitoring Mission long-term resolution more challenging. region of Eastern Ukraine. The Ukrai- to Ukraine (OSCE-SMM). Despite Most importantly, freezing the conflict nian government has repeatedly called halting progress since that time, restart- in its current state would solidify Russian for a peacekeeping mission to halt ing a peacekeeping mission remains an control of the separatist regions, enabling the bloodshed, so Russian President important opportunity.1 Many experts it to maintain pressure on Ukraine by Vladimir Putin surprised the world on remain wary and dismiss it as a politi- adjusting the intensity level as it de- sires. -

Petroleum Geology and Resources of the Dnieper-Donets Basin, Ukraine and Russia

Petroleum Geology and Resources of the Dnieper-Donets Basin, Ukraine and Russia By Gregory F. Ulmishek U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2201-E U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director Version 1.0, 2001 This publication is only available online at: http://geology.cr.usgs.gov/pub/bulletins/b2201-e/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Manuscript approved for publication July 3, 2001 Published in the Central Region, Denver, Colorado Graphics by Susan Walden and Gayle M. Dumonceaux Photocomposition by Gayle M. Dumonceaux Contents Foreword ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Abstract.......................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 2 Province Overview ....................................................................................................................... 2 Province Location and Boundaries................................................................................. 2 Tectono-Stratigraphic Development ............................................................................. -

Boris Nemtsov 27 February 2015 Moscow, Russia

Boris Nemtsov 27 February 2015 Moscow, Russia the fight against corruption, embezzlement and fraud, claiming that the whole system built by Putin was akin to a mafia. In 2009, he discovered that one of Putin’s allies, Mayor of Moscow City Yury Luzhkov, BORIS and his wife, Yelena Baturina, were engaged in fraudulent business practices. According to the results of his investigation, Baturina had become a billionaire with the help of her husband’s connections. Her real-estate devel- opment company, Inteco, had invested in the construction of dozens of housing complexes in Moscow. Other investors were keen to part- ner with Baturina because she was able to use NEMTSOV her networks to secure permission from the Moscow government to build apartment build- ings, which were the most problematic and It was nearing midnight on 27 February 2015, and the expensive construction projects for developers. stars atop the Kremlin towers shone with their charac- Nemtsov’s report revealed the success of teristic bright-red light. Boris Nemtsov and his partner, Baturina’s business empire to be related to the Anna Duritskaya, were walking along Bolshoy Moskovo- tax benefits she received directly from Moscow retsky Bridge. It was a cold night, and the view from the City government and from lucrative govern- bridge would have been breathtaking. ment tenders won by Inteco. A snowplough passed slowly by the couple, obscuring the scene and probably muffling the sound of the gunshots fired from a side stairway to the bridge. The 55-year-old Nemtsov, a well-known Russian politician, anti-corrup- tion activist and a fierce critic of Vladimir Putin, fell to the ground with four bullets in his back. -

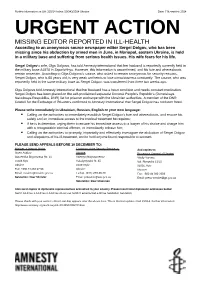

Urgent Action

Further information on UA: 215/14 Index: 50/043/2014 Ukraine Date: 7 November 2014 URGENT ACTION MISSING EDITOR REPORTED IN ILL-HEALTH According to an anonymous source newspaper editor Sergei Dolgov, who has been missing since his abduction by armed men in June, in Mariupol, eastern Ukraine, is held in a military base and suffering from serious health issues. His wife fears for his life. Sergei Dolgov’s wife, Olga Dolgova, has told Amnesty international that her husband is reportedly currently held in the military base A1978 in Zaporizhhya. However, this information is unconfirmed, and his fate and whereabouts remain uncertain. According to Olga Dolgova’s source, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons, Sergei Dolgov, who is 60 years old, is very weak and tends to lose consciousness constantly. The source, who was reportedly held in the same military base as Sergei Dolgov, was transferred from there two weeks ago. Olga Dolgova told Amnesty International that her husband has a heart condition and needs constant medication. Sergei Dolgov has been placed on the self-proclaimed separatist Donetsk People’s Republic‘s (Donetskaya Narodnaya Respublika, DNR) list for prisoner exchange with the Ukrainian authorities. A member of the DNR Council for the Exchange of Prisoners confirmed to Amnesty International that Sergei Dolgov has not been freed. Please write immediately in Ukrainian, Russian, English or your own language: . Calling on the authorities to immediately establish Sergei Dolgov’s fate and whereabouts, and ensure his safety and an immediate access to the medical treatment he requires; . If he is in detention, urging them to ensure his immediate access to a lawyer of his choice and charge him with a recognizable criminal offence, or immediately release him; . -

Ukrainian Far Right

Nations in Transit brief May 2018 Far-right Extremism as a Threat to Ukrainian Democracy Vyacheslav Likhachev Kyiv-based expert on right-wing groups in Ukraine and Russia Photo by Aleksandr Volchanskiy • Far-right political forces present a real threat to the democratic development of Ukrainian society. This brief seeks to provide an overview of the nature and extent of their activities, without overstating the threat they pose. To this end, the brief differentiates between radical groups, which by and large ex- press their ideas through peaceful participation in democratic processes, and extremist groups, which use physical violence as a means to influence society. • For the first 20 years of Ukrainian independence, far-right groups had been undisputedly marginal elements in society. But over the last few years, the situation has changed. After Ukraine’s 2014 Euro- maidan Revolution and Russia’s subsequent aggression, extreme nationalist views and groups, along with their preachers and propagandists, have been granted significant legitimacy by the wider society. • Nevertheless, current polling data indicates that the far right has no real chance of being elected in the upcoming parliamentary and presidential elections in 2019. Similarly, despite the fact that several of these groups have real life combat experience, paramilitary structures, and even access to arms, they are not ready or able to challenge the state. • Extremist groups are, however, aggressively trying to impose their agenda on Ukrainian society, in- cluding by using force against those with opposite political and cultural views. They are a real physical threat to left-wing, feminist, liberal, and LGBT activists, human rights defenders, as well as ethnic and religious minorities. -

Ukraine Resolution on Mariupol.Pdf (23.08

DAV15155 S.L.C. 114TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION S. RES. ll Expressing the sense of the Senate regarding the January 24, 2015, attacks carried out by Russian-backed rebels on the civilian population in Mariupol, Ukraine, and the provision of lethal and non-lethal military assistance to Ukraine. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES llllllllll Mr. JOHNSON (for himself and Mrs. SHAHEEN) submitted the following resolution; which was referred to the Committee on llllllllll RESOLUTION Expressing the sense of the Senate regarding the January 24, 2015, attacks carried out by Russian-backed rebels on the civilian population in Mariupol, Ukraine, and the provision of lethal and non-lethal military assistance to Ukraine. Whereas Russian-backed rebels continue to expand their cam- paign in Ukraine, which has already claimed more than 5,000 lives and generated an estimated 1,500,000 refu- gees and internally displaced persons; Whereas, on January 23, 2015, Russian rebels pulled out of peace talks with Western leaders; DAV15155 S.L.C. 2 Whereas, on January 24, 2015, the Ukrainian port city of Mariupol received rocket fire from territory in the Donetsk region controlled by rebels; Whereas, on January 24, 2015, Alexander Zakharchenko, leader of the Russian-backed rebel Donetsk People’s Re- public, publicly announced that his troops had launched an offensive against Mariupol; Whereas Mariupol is strategically located on the Sea of Azov and is a sea link between Russian-occupied Crimea and Russia, and could be used to form part of a land bridge between Crimea and -

Hybrid Warfare and the Protection of Civilians in Ukraine

ENTERING THE GREY-ZONE: Hybrid Warfare and the Protection of Civilians in Ukraine civiliansinconflict.org i RECOGNIZE. PREVENT. PROTECT. AMEND. PROTECT. PREVENT. RECOGNIZE. Cover: June 4, 2013, Spartak, Ukraine: June 2021 Unexploded ordnances in Eastern Ukraine continue to cause harm to civilians. T +1 202 558 6958 E [email protected] civiliansinconflict.org ORGANIZATIONAL MISSION AND VISION Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) is an international organization dedicated to promoting the protection of civilians in conflict. CIVIC envisions a world in which no civilian is harmed in conflict. Our mission is to support communities affected by conflict in their quest for protection and strengthen the resolve and capacity of armed actors to prevent and respond to civilian harm. CIVIC was established in 2003 by Marla Ruzicka, a young humanitarian who advocated on behalf of civilians affected by the war in Iraq and Afghanistan. Honoring Marla’s legacy, CIVIC has kept an unflinching focus on the protection of civilians in conflict. Today, CIVIC has a presence in conflict zones and key capitals throughout the world where it collaborates with civilians to bring their protection concerns directly to those in power, engages with armed actors to reduce the harm they cause to civilian populations, and advises governments and multinational bodies on how to make life-saving and lasting policy changes. CIVIC’s strength is its proven approach and record of improving protection outcomes for civilians by working directly with conflict-affected communities and armed actors. At CIVIC, we believe civilians are not “collateral damage” and civilian harm is not an unavoidable consequence of conflict—civilian harm can and must be prevented. -

Citizens and the State in the Government-Controlled Territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk Regions Problems, Challenges and Visions of the Future

Citizens and the state in the government-controlled territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions Problems, challenges and visions of the future Funded by: This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union through International Alert. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of International Alert and UCIPR and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. Layout: Nick Wilmot Creative Front cover image: A mother and daughter living in temporary accommodation for those displaced by the violence in Donetsk, 2014. © Andrew McConnell/Panos © International Alert/Ukrainian Center for Independent Political Research 2017 Citizens and the state in the government-controlled territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions Problems, challenges and visions of the future October 2017 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. Methodology 6 3. Findings 7 4. Statements from interviewees 22 5. Conclusions and recommendations 30 Citizens and the state in the government-controlled territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions 3 1. INTRODUCTION The demarcation line (the line of contact)1 and the ‘grey zone’ between the government-controlled2 and uncontrolled territories3 of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions separates the parties to the conflict in the east of Ukraine. The areas controlled by the Ukrainian authorities and bordering the ‘grey zone’ are very politically sensitive, highly militarised, and fall under a special governance regime that is different from the rest of the country. In the absence of a comprehensive political settlement and amid uncertain prospects, it is unclear how long this situation will remain. It is highly likely that over the next few years, Ukrainians in areas adjacent to the contact line will live under very particular and unusual governance structures, and in varying degrees of danger.