A Liminal Existence, Literally

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nominations�1

Section of the WSFS Constitution says The complete numerical vote totals including all preliminary tallies for rst second places shall b e made public by the Worldcon Committee within ninety days after the Worldcon During the same p erio d the nomination voting totals shall also b e published including in each category the vote counts for at least the fteen highest votegetters and any other candidate receiving a numb er of votes equal to at least ve p ercent of the nomination ballots cast in that category The Hugo Administrator reports There were valid nominating ballots and invalid nominating ballots There were nal ballots received of which were valid Most of the invalid nal ballots were electronic ballots with errors in voting which were corrected by later resubmission by the memb ers only the last received ballot for each memb er was counted Best Novel 382 nominating ballots cast 65 Brasyl by Ian McDonald 58 The Yiddish Policemens Union by Michael Chab on 58 Rol lback by Rob ert J Sawyer 41 The Last Colony by John Scalzi 40 Halting State by Charles Stross 30 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hal lows by J K Rowling 29 Making Money by Terry Pratchett 29 Axis by Rob ert Charles Wilson 26 Queen of Candesce Book Two of Virga by Karl Schro eder 25 Accidental Time Machine by Jo e Haldeman 25 Mainspring by Jay Lake 25 Hapenny by Jo Walton 21 Ragamun by Tobias Buckell 20 The Prefect by Alastair Reynolds 19 The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss Best Novella 220 nominating ballots cast 52 Memorare by Gene Wolfe 50 Recovering Ap ollo -

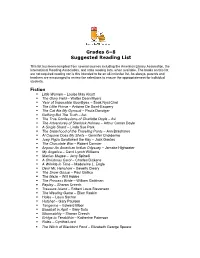

Grades 6-8 Suggested Reading List

Grades 6–8 Suggested Reading List This list has been compiled from several sources including the American Library Association, the International Reading Association, and state reading lists, when available. The books on this list are not required reading nor is this intended to be an all-inclusive list. As always, parents and teachers are encouraged to review the selections to ensure the appropriateness for individual students. Fiction . Little Women – Louise May Alcott . The Glory Field – Walter Dean Myers . Year of Impossible Goodbyes – Sook Nyui Choi . The Little Prince – Antoine De Saint-Exupery . The Cat Ate My Gymsuit – Paula Danziger . Nothing But The Truth – Avi . The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle – Avi . The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Arthur Conan Doyle . A Single Shard – Linda Sue Park . The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants – Ann Brashares . Al Capone Does My Shirts – Gennifer Choldenko . Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key – Jack Gantos . The Chocolate War – Robert Cormier . Anpao: An American Indian Odyssey – Jamake Highwater . My Angelica – Carol Lynch Williams . Maniac Magee – Jerry Spinelli . A Christmas Carol – Charles Dickens . A Wrinkle in Time – Madeleine L. Engle . Dear Mr. Henshaw – Beverly Cleary . The Snow Goose – Paul Gallico . The Maze – Will Hobbs . The Princess Bride – William Goldman . Replay – Sharon Creech . Treasure Island – Robert Louis Stevenson . The Westing Game – Ellen Raskin . Holes – Louis Sachar . Hatchet – Gary Paulsen . Tangerine – Edward Bloor . Baseball in April – Gary Soto . Bloomability – Sharon Creech . Bridge to Terabithia – Katherine Paterson . Rules – Cynthia Lord . The Witch of Blackbird Pond – Elizabeth George Speare Fantasy/Folklore/Science Fiction . Redwall (series) – Brian Jacques . Howl’s Moving Castle – Diana Wynne Jones . -

Time Control in Diana Wynne Jones's Fiction: the Chronicles of Chrestomanci

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e letterature europee americane e post coloniali Tesi di Laurea Ca’ Foscari Dorsoduro 3246 30123 Venezia Time Control in Diana Wynne Jones’s Fiction: The Chronicles of Chrestomanci Relatore Ch.ma Prof. Laura Tosi Correlatore Ch.mo Prof. Marco Fazzini Laureando Giada Nerozzi Matricola 841931 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 Table of Contents 1Introducing Diana Wynne Jones........................................................................................................3 1.1A Summary of Jones's Biography...............................................................................................3 1.2An Overview of Wynne Jones's Narrative Features and Themes...............................................4 1.3Diana Wynne Jones and Literary Criticism................................................................................6 2Time and Space Treatment in Chrestomanci Series...........................................................................7 2.1Introducing Time........................................................................................................................7 2.2The Nature of Time Travel.......................................................................................................10 2.2.1Time Traveller and Time according to Wynne Jones.......................................................10 2.2.2Common Subjects in Time Travel Stories........................................................................11 2.2.3Comparing and Contrasting -

Australian SF News 39

DON TUCK WINS HUGO Tasmanian fan and bibliophile, DONALD H.TUCK, has won a further award for his work in the science fiction and fantasy reference field, with his ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE FICTION AND 'FANTASY Volume III, which won the Non-Fiction Hugo Award at the World SF Convention, LA-CON, held August 30th to September 3rd. Don was previously presented with a Committee Award by the '62 World SF Co, Chicon III; for his work on THE HANDBOOK OF SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY, which grew into the three volume encyclopedia published by Advent : Publishers Inc. in Chicago, Illinois,U.S.A. Winning the Hugo Award, the first one presented to an Australian fan or professional, is a fitting reward for the tremendous amount of time and effort Don has put into his very valuable reference work. ( A profile of Don appears on page 12.) 8365 People Attend David Brin's STARTIDE RISING wins DONALD H.TUCK C. D.H.Tuck '84 Hugo Best Novel Award L.A.CON, the 42nd World SF Convention, was the largest World SF Con held so far. The Anaheim Convention Centre in Anaheim California, near Hollywood, was the centre of the activities which apparently took over where the Olympic Games left off. 9282 people joined the convention with 8365 actually attending. 2542 people joined at the door, despite the memberships costs of $35 a day and $75 for the full con. Atlanta won the bld to hold the 1986 World SF Convention, on the first ballot, with 789 out of the total of valid votes cast of 1368. -

The Tough Guide to Fantasyland

The Tough Guide to Fantasyland Diana Wynne Jones Scanned by Cluttered Mind HOW TO USE THIS BOOK WHAT TO DO FIRST 1. Find the MAP. It will be there. No Tour of Fantasyland is complete without one. It will be found in the front part of your brochure, quite near the page that says For Mom and Dad for having me and for Jeannie (or Jack or Debra or Donnie or …) for putting up with me so supportively and for my nine children for not interrupting me and for my Publisher for not discouraging me and for my Writers’ Circle for listening to me and for Barbie and Greta and Albert Einstein and Aunty May and so on. Ignore this, even if you are wondering if Albert Einstein is Albert Einstein or in fact the dog. This will be followed by a short piece of prose that says When the night of the wolf waxes strong in the morning, the wise man is wary of a false dawn. Ka’a Orto’o, Gnomic Utterances Ignore this too (or, if really puzzled, look up GNOMIC UTTERANCES in the Toughpick section). Find the Map. 2. Examine the Map. It will show most of a continent (and sometimes part of another) with a large number of BAYS, OFFSHORE ISLANDS, an INLAND SEA or so and a sprinkle of TOWNS. There will be scribbly snakes that are probably RIVERS, and names made of CAPITAL LETTERS in curved lines that are not quite upside down. By bending your neck sideways you will be able to see that they say things like “Ca’ea Purt’wydyn” and “Om Ce’falos.” These may be names of COUNTRIES, but since most of the Map is bare it is hard to tell. -

The Role of Critical Literacy in Challenging the Status Quo in Twentieth Century English Children’S Literature

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2018 The Role of Critical Literacy in Challenging the Status Quo in Twentieth Century English Children’s Literature Rene Fleischbein University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Fleischbein, Rene, "The Role of Critical Literacy in Challenging the Status Quo in Twentieth Century English Children’s Literature" (2018). Dissertations. 1556. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1556 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROLE OF CRITICAL LITERACY IN CHALLENGING THE STATUS QUO IN TWENTIETH CENTURY ENGLISH CHILDREN’S LITERATURE by René Elizabeth Fleischbein A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters and the Department of English at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Dr. Jameela Lares, Committee Chair Dr. Eric Tribunella Dr. Katherine Cochran Dr. Damon Franke Dr. Farah Mendlesohn ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Jameela Lares Dr. Luis Iglesias Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Department Chair Dean of the Graduate School August 2018 COPYRIGHT BY René Elizabeth Fleischbein 2018 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT Although many children’s literature critics focus on the two divides between instruction and delight and between the fantastic and the realist, this dissertation focuses on the occurrences in twentieth century English children’s fantasy of critical literacy, a mode of reading that challenges the status quo of society and gives voice to underrepresented and marginalized groups. -

{PDF EPUB} Hexwood by Diana Wynne Jones Hexwood

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Hexwood by Diana Wynne Jones Hexwood. This is, unfortunately, a book with too many good ideas and not enough structure or characterization. I say unfortunately because some of the ideas are great. I can't talk about all of them, since piecing them together is a substantial part of the plot and probably the best part of the book, but there's ancient powerful machinery, a fair bit of fiddling about with time (time travel just isn't the right term), some nice non-linear exposition, a galaxy-spanning empire secretly well-established on Earth, some truly nice mind-link telepathy, and a really fun take on magic. On top of that, though, there's also a bit of an Arthurian, some badly done political intrigue and infighting, dragons, badly handled mind control, angst about a dark past, mythical nature, and robots. You may be seeing what I mean about too many ideas. There's something of an overall structure that allows one to sensibly mash all of this stuff together, but it still feels like a disjointed hodge-podge. Worse, though, is that due to the machine-gun speed at which ideas, plot elements, and bits of background are introduced, the really good ones don't get explored. One is left with an extensive list of things in the "this could have been cool if anything had really been done with it" category. I wish some of this could have been spread out across two or three completely different books so that I could have enjoyed a fully-fleshed version. -

The Orphan Figure in Latter Twentieth Century Anglo-American Children's

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-1-2016 In Absentia Parentis: The Orphan Figure in Latter Twentieth Century Anglo-American Children’s Fantasy James Michael Curtis University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Curtis, James Michael, "In Absentia Parentis: The Orphan Figure in Latter Twentieth Century Anglo- American Children’s Fantasy" (2016). Dissertations. 322. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/322 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN ABSENTIA PARENTIS: THE ORPHAN FIGURE IN LATTER TWENTIETH CENTURY ANGLO-AMERICAN CHILDREN’S FANTASY by James Michael Curtis A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School and the Department of English at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: ________________________________________________ Dr. Jameela Lares, Committee Chair Professor, English ________________________________________________ Dr. Eric Tribunella, Committee Member Associate Professor, English ________________________________________________ Dr. Charles Sumner, Committee Member Associate -

Reviews: Ed Mcknight Fiction Reviews: Philip Snyder

#257 Mar.-Apr. 2002 Coeditors: Barbara Lucas Shelley Rodrigo Blanchard Nonfiction Reviews: Ed McKnight Fiction Reviews: Philip Snyder The SFRAReview (ISSN IN THIS ISSUE: 1068-395X) is published six times a year by the Science Fiction Research Association (SFRA) and distributed SFRA Business to SFRA members.NONNON Individual issues are not for sale; however, starting with Candidates Statements 2 issue #256, all issues will be pub- Clareson Award Presentation lished to SFRA’s website no less than Speech 2001 4 two months after paper publication. For information about the SFRA and its benefits, see the description at the Non Fiction Reviews back of this issue. For a membership A. E. van Vogt 6 application, contact SFRA Treasurer Being Gardner Dozoiz 7 Dave Mead or get one from the SFRA website: <www.sfra.org>. Tolkien’s Art & The Lord of the Rings 9 Star Trek: The Human Frontier 11 SUBMISSIONS Star Trek and Sacred Ground 12 The SFRAReview editors encourage submissions, including essays, review Interacting with Babylon 5 13 essays that cover several related texts, Science Fiction Cinema 14 and interviews. Please send submis- What If? 2 15 sions or queries to both coeditors. If you would like to review nonfiction The Horror Genre 17 or fiction, please contact the Fantasy of the 20th Century 18 respective editor and/or email [email protected] [email protected][email protected]. Fiction Reviews Barbara Lucas, Coeditor Jenna Starborn 19 1352 Fox Run Drive, Suite 206 Picoverse 19 Willoughby, OH 44094 Picoverse 19 <[email protected]> Ombria in Shadow 20 Mars Probes 22 Shelley Rodrigo Blanchard, Coeditor 6842 S. -

Diana Wynne Jones Saying That Her Novels ‘Provide a Space Where Children Can

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2009 "Mum’s a silly fusspot”: the queering of family in Diana Wynne Ika Willis University of Bristol, [email protected] Publication Details I. Willis (2009). "Mum’s a silly fusspot”: the queering of family in Diana Wynne. University of the West of England, Bristol, 4 July. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] "Mum’s a silly fusspot”: the queering of family in Diana Wynne Abstract In Four British Fantasists, Butler cites Diana Wynne Jones saying that her novels ‘provide a space where children can... walk round their problems and think “Mum’s a silly fusspot and I don’t need to be quite so enslaved by her notions”‘ (267). That is, as I will argue in this paper, Jones’ work aims to provide readers with the emotional, narrative and intellectual resources to achieve a critical distance from their families of origin. I will provide a brief survey of the treatment of family in Jones’ children’s books, with particular reference to Charmed Life, The Lives of Christopher Chant, The grO e Downstairs, Cart and Cwidder, Drowned Ammet, The omeH ward Bounders and Hexwood, and then narrow my focus to two of Jones’ classic 4 treatments of family: Eight Days of Luke and Archer’s Goon. I will read these books in terms of the ways in which their child protagonists reposition themselves in relation to family in the course of their narratives. -

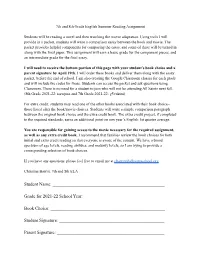

7Th and 8Th Grade English Summer Reading Assignment

7th and 8th Grade English Summer Reading Assignment Students will be reading a novel and then watching the movie adaptation. Using tools I will provide in a packet, students will write a comparison essay between the book and movie. The packet provides helpful components for composing the essay, and some of these will be turned in along with the final paper. This assignment will earn a basic grade for the component pieces, and an intermediate grade for the final essay. I will need to receive the bottom portion of this page with your student’s book choice and a parent signature by April 19th. I will order these books and deliver them along with the essay packet, before the end of school. I am also creating the Google Classroom classes for each grade and will include the codes for those. Students can access the packet and ask questions using Classroom. There is no need for a student to join who will not be attending All Saints next fall. (8th Grade 2021-22: isawjmx and 7th Grade 2021-22: g5vuktm) For extra credit, students may read one of the other books associated with their book choice-- those listed after the book/movie choices. Students will write a simple comparison paragraph between the original book choice and the extra credit book. The extra credit project, if completed to the required standards, earns an additional point on nex year’s English 1st quarter average. You are responsible for gaining access to the movie necessary for the required assignment, as well as any extra credit book. -

Now a Major Motion Picture Outline

Now A Major Motion Picture Outline Tutor: Sam Maxfield Starts Monday January 13 2020, 7.00pm, 10 weeks Week 1: Now a Major Motion Picture – an introduction to some of the key terms, techniques and concepts involved in ‘translating’ literary narrative to film narrative. Week 2: When the Film Is Better Than the Book – exploring why Spielberg’s Jaws artistically transcends the bestselling blockbuster it was based on. Week 3: The Trouble with Mr Rochester – how capturing the rich Gothic Romance and beloved characters of Jane Eyre have proved problematic in big screen adaptations. Week 4: From Epic Adaptation to Portentous Bloat – Peter Jackson generally triumphed with his adaptation of Lord of the Rings but would his inflated tampering with The Hobbit have Tolkien turning in his grave? Week 5: Literary Dazzlement to Screen Disappointment? – Toni Morrison’s masterpiece Beloved is a complex and challenging piece of literature, narratively, stylistically and emotionally. Was it possible Oprah Winfrey and Jonathon Demme to bring it to the screen successfully? Week 6: Author Versus Auteur – Stephen King famously took umbrage at Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of King’s novel The Shining. Here we explore the changes Kubrick made and why. Week 7: Lost in Translation? – How Japanese anime director Hayao Miyazaki aimed to capture the European flavour of Diana Wynne Jones’s children’s fantasy novel Howl’s Moving Castle while retaining the quintessential Studio Ghibli style. Week 8: When Two Become One – Barry Hine’s novel A Kestrel for a Knave is often referred to as the film’s title, Kes, indicating how inextricably entwined the book and film is in people’s minds.