Garner and the Regional Gothic Timothy Jones for STORRE.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tolkien, Hispanic, Koonts, Evanovich Bkmrks.Pub

Fantasy for Tolkien fans Hispanic Authors If you like J.R.R. Tolkien, why not give these authors a try? Kathleen Alcala Machado de Assis Piers Anthony Robert Jordan Julia Alvarez Gabriel Garcia Marquez A.A. Attanasio Guy Kavriel Kay Isabel Allende Ana Menendez Marion Zimmer Bradley Tanith Lee Jorge Amado Michael Nava Terry Brooks Ursula K. LeGuin Rudolfo Anaya Arturo Perez-Reverte Lois McMaster Bujold George R. R. Martin Gioconda Belli Manuel Puig Susan Cooper L.E. Modesitt Sandra Benitez Jose Saramago John Crowley Elizabeth Moon Jorge Luis Borges Mario Vargas Llosa Tom Deitz Andre Norton Ana Castillo Alfredo Vea Charles de Lint Mervyn Peake Miguel de Cervantes David Eddings Terry Pratchett Denise Chavez Eric Flint Philip Pullman Sandra Cisneros Alan Dean Foster Neal Stephenson Paulo Coehlo C. S. Friedman Harry Turtledove Humberto Costantini Neil Gaiman Margaret Weis Jose Donoso 7/05 Barbara Hambly Connie Willis Laura Esquivel Elizabeth Hand Roger Zelazny Carlos Fuentes Tracy Hickman Cristina Garcia Oscar Hijuelos 7/05 ]tÇxà XätÇÉä|v{ If you like Dean Koontz 7/05 Janet Evanovich, Romantic mysteries you might like: Pseudonyms of Dean Martin H. Greenberg filled with action Susan Andersen Koontz: Caitlin Kiernan and humor. J.S. Borthwick David Axton Stephen King Stephanie Plum Jan Burke Brian Coffey Joe Lansdale Dorothy Cannell Mysteries K.R. Dwyer James Lasdun Harlan Coben One for the money Leigh Nichols Ira Levin Jennifer Crusie Two for the dough Anthony North Bentley Little Jennifer Drew Three to get deadly Richard Paige H.P. Lovecraft G.M. Ford Four to score Owen West Robin McKinley Kinky Friedman High five Sue Grafton Graham Masterton Hot six Heather Graham If you like Dean Koontz, Richard Matheson Seven up Sparkle Hayter you might like: Joyce Carol Oates Hard eight Carl Hiassen Richard Bachman Tom Piccirilli To the nines P.D. -

K¹² Recommended Reading 2012

K12 Recommended Reading 2012 K¹² Recommended Reading 2012 Every child learns in his or her own way. Yet many classrooms try to make one size fit all. K¹² creates a classroom of one: a remarkably effective education option that is individualized to meet each child's needs. K¹² education options include: Full-time, tuition-free online public schooling available in many states An accredited online private school available worldwide, full- and part-time Over 200 courses, including AP and world languages, for direct purchase We have a 96% satisfaction rating* from parents. Isn't it time you found out how online learning works? Visit our website at www.k12.com for full details and free sample lessons! *Source: K-3 Experience Survey, TRC Recommended Reading for Kids at Every Level The K¹² reading experts who created our Language Arts courses invite you to enjoy our ‘Recommended Reading” list for grades K–12. Kindergarten The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle The Z was Zapped by Chris Van Allsburg Alison's Zinnia by Anita Lobel Brown Bear, Brown Bear by Eric Carle Wifred Gordon McDonald Partridge by Mem Fox The Napping House by Don & Audrey Wood Rosie's Walk by Pat Hutchins Sheep in a Jeep by Nancy Shaw Corduroy by Don Freeman K12 Recommended Reading 2012 Grades 1–2 Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day by Judith Viorst The Day Jimm's Boa Ate the Wash by Trinka Hake Noble Huge Harold by Bill Peet The Doorbell Rang by Pat Hutchins Young Cam Jansen series by David Adler – Young Cam Jansen and the Missing -

Nominations�1

Section of the WSFS Constitution says The complete numerical vote totals including all preliminary tallies for rst second places shall b e made public by the Worldcon Committee within ninety days after the Worldcon During the same p erio d the nomination voting totals shall also b e published including in each category the vote counts for at least the fteen highest votegetters and any other candidate receiving a numb er of votes equal to at least ve p ercent of the nomination ballots cast in that category The Hugo Administrator reports There were valid nominating ballots and invalid nominating ballots There were nal ballots received of which were valid Most of the invalid nal ballots were electronic ballots with errors in voting which were corrected by later resubmission by the memb ers only the last received ballot for each memb er was counted Best Novel 382 nominating ballots cast 65 Brasyl by Ian McDonald 58 The Yiddish Policemens Union by Michael Chab on 58 Rol lback by Rob ert J Sawyer 41 The Last Colony by John Scalzi 40 Halting State by Charles Stross 30 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hal lows by J K Rowling 29 Making Money by Terry Pratchett 29 Axis by Rob ert Charles Wilson 26 Queen of Candesce Book Two of Virga by Karl Schro eder 25 Accidental Time Machine by Jo e Haldeman 25 Mainspring by Jay Lake 25 Hapenny by Jo Walton 21 Ragamun by Tobias Buckell 20 The Prefect by Alastair Reynolds 19 The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss Best Novella 220 nominating ballots cast 52 Memorare by Gene Wolfe 50 Recovering Ap ollo -

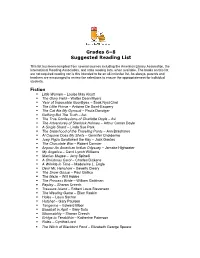

Grades 6-8 Suggested Reading List

Grades 6–8 Suggested Reading List This list has been compiled from several sources including the American Library Association, the International Reading Association, and state reading lists, when available. The books on this list are not required reading nor is this intended to be an all-inclusive list. As always, parents and teachers are encouraged to review the selections to ensure the appropriateness for individual students. Fiction . Little Women – Louise May Alcott . The Glory Field – Walter Dean Myers . Year of Impossible Goodbyes – Sook Nyui Choi . The Little Prince – Antoine De Saint-Exupery . The Cat Ate My Gymsuit – Paula Danziger . Nothing But The Truth – Avi . The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle – Avi . The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Arthur Conan Doyle . A Single Shard – Linda Sue Park . The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants – Ann Brashares . Al Capone Does My Shirts – Gennifer Choldenko . Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key – Jack Gantos . The Chocolate War – Robert Cormier . Anpao: An American Indian Odyssey – Jamake Highwater . My Angelica – Carol Lynch Williams . Maniac Magee – Jerry Spinelli . A Christmas Carol – Charles Dickens . A Wrinkle in Time – Madeleine L. Engle . Dear Mr. Henshaw – Beverly Cleary . The Snow Goose – Paul Gallico . The Maze – Will Hobbs . The Princess Bride – William Goldman . Replay – Sharon Creech . Treasure Island – Robert Louis Stevenson . The Westing Game – Ellen Raskin . Holes – Louis Sachar . Hatchet – Gary Paulsen . Tangerine – Edward Bloor . Baseball in April – Gary Soto . Bloomability – Sharon Creech . Bridge to Terabithia – Katherine Paterson . Rules – Cynthia Lord . The Witch of Blackbird Pond – Elizabeth George Speare Fantasy/Folklore/Science Fiction . Redwall (series) – Brian Jacques . Howl’s Moving Castle – Diana Wynne Jones . -

![The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 Edition]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8392/the-best-childrens-books-of-the-year-2020-edition-1158392.webp)

The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 Edition]

Bank Street College of Education Educate The Center for Children's Literature 4-14-2020 The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition] Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee (2020). The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition]. Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl/ 10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Center for Children's Literature by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bank Street College of Education Educate The Center for Children's Literature 4-14-2020 The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition] Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee (2020). The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition]. Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl/ 10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Center for Children's Literature by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

Time Control in Diana Wynne Jones's Fiction: the Chronicles of Chrestomanci

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e letterature europee americane e post coloniali Tesi di Laurea Ca’ Foscari Dorsoduro 3246 30123 Venezia Time Control in Diana Wynne Jones’s Fiction: The Chronicles of Chrestomanci Relatore Ch.ma Prof. Laura Tosi Correlatore Ch.mo Prof. Marco Fazzini Laureando Giada Nerozzi Matricola 841931 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 Table of Contents 1Introducing Diana Wynne Jones........................................................................................................3 1.1A Summary of Jones's Biography...............................................................................................3 1.2An Overview of Wynne Jones's Narrative Features and Themes...............................................4 1.3Diana Wynne Jones and Literary Criticism................................................................................6 2Time and Space Treatment in Chrestomanci Series...........................................................................7 2.1Introducing Time........................................................................................................................7 2.2The Nature of Time Travel.......................................................................................................10 2.2.1Time Traveller and Time according to Wynne Jones.......................................................10 2.2.2Common Subjects in Time Travel Stories........................................................................11 2.2.3Comparing and Contrasting -

Recommended Reading

Recommended Reading 1. An English-English Dictionary - the first book you should buy in Chicago. Buy one. Now. Very Easy-to-Easy (Fiction/ Novels): Fiction featuring child characters 2. The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros- set in Chicago; easy-to-read with short chapters 3. The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupery- a timeless classic by a famous French author 4. Holes by Louis Sachar-young kids find an adventure after digging holes for punishment 5. Esperanza Rising by Pam Munoz Ryan-deals with Mexican immigration 6. The Pigman by Paul Zindel- two young people learn to appreciate life from an old man 7. Frannie and Zooey by J.D. Salinger- the story of a young brother and sister 8. Superfudge by Judy Blume-a young boy’s adventures and troubles; a very funny book 9. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie- a funny book with cartoons 10. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl- the inspiration of two different movies,(Johnny Depp) 11. James and the Giant Peach by Roald Dahl-a small orphan boy has many magical adventures 12. The Single Shard by Linda Sue Park-a story of Korean history 13. Wringer by Jerry Spinelli-a story of young boys and peer pressure 14. Bridge to Terebithia by Katherine Paterson-a sweet story about a friendship 15. The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton-a story of friendship, murder, gangs and social status 16. The Pearl by John Steinbeck-a Mexican folktale about a poor fisherman and a pearl 17. -

Australian SF News 39

DON TUCK WINS HUGO Tasmanian fan and bibliophile, DONALD H.TUCK, has won a further award for his work in the science fiction and fantasy reference field, with his ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE FICTION AND 'FANTASY Volume III, which won the Non-Fiction Hugo Award at the World SF Convention, LA-CON, held August 30th to September 3rd. Don was previously presented with a Committee Award by the '62 World SF Co, Chicon III; for his work on THE HANDBOOK OF SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY, which grew into the three volume encyclopedia published by Advent : Publishers Inc. in Chicago, Illinois,U.S.A. Winning the Hugo Award, the first one presented to an Australian fan or professional, is a fitting reward for the tremendous amount of time and effort Don has put into his very valuable reference work. ( A profile of Don appears on page 12.) 8365 People Attend David Brin's STARTIDE RISING wins DONALD H.TUCK C. D.H.Tuck '84 Hugo Best Novel Award L.A.CON, the 42nd World SF Convention, was the largest World SF Con held so far. The Anaheim Convention Centre in Anaheim California, near Hollywood, was the centre of the activities which apparently took over where the Olympic Games left off. 9282 people joined the convention with 8365 actually attending. 2542 people joined at the door, despite the memberships costs of $35 a day and $75 for the full con. Atlanta won the bld to hold the 1986 World SF Convention, on the first ballot, with 789 out of the total of valid votes cast of 1368. -

Book List for Elementary Gifted Students

Book List for Elementary Gifted Students Genre Book Title Author Adventure My Side of the Mountain J. C. George Adventure Pippi Longstocking Astrin Lundgren Adventure/Fantasy Rowan of Rin Series Emily Rodda Adventure/Historical Fiction Hatchet/Mr. Tucket Series Gary Paulsen Fantasy Ella Enchanted Gail Carson Levine Fantasy Catherine, Called Birdy Karen Cushman Fantasy The Dark is Rising Susan Cooper Fantasy Book of Three Lloyd Alexander Fantasy Dragon Rider Cornelia Funke Fantasy The Littles* John Peterson Fantasy Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle* Betty MacDonald Fantasy The Phantom Tollbooth Norton Juster Fantasy The Lightning Thief Rick Riordan Fantasy The Time Warp Trio Series* John Scieszka Fantasy The Borrowers* Mary Morton Fantasy Babe and others Dick King-Smith Fantasy Matilda and others* Roald Dahl Fantasy/Mystery Hank the Cowdog John Erickson Historical Fiction Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry M. Taylor Mystery A-Z Mystery Series* Ron Roy Mystery Chasing Vermeer Blue Balliett Mystery Nate the Great* Marjorie Sharmat Mystery Cam Jansen* David Adler Mystery Westing Game E. Raskin Mystery Encyclopedia Brown Series* Donald Sobol Realistic Fiction Ramona Series* Beverly Cleary Realistic Fiction The Secret Garden F.H. Burnett Realistic Fiction Frindle*/Things Not Seen Andrew Clements Realistic Fiction Twinkie Squad/Schooled Gordon Korman Realistic Fiction Henry Reed series Keith Robertson Realistic Fiction View from Saturday E.L. Konigsburg Realistic Fiction The Moffats Series Eleanor Estes Realistic Fiction The Great Brain JD Fitzgerald Science Fiction -

The Tough Guide to Fantasyland

The Tough Guide to Fantasyland Diana Wynne Jones Scanned by Cluttered Mind HOW TO USE THIS BOOK WHAT TO DO FIRST 1. Find the MAP. It will be there. No Tour of Fantasyland is complete without one. It will be found in the front part of your brochure, quite near the page that says For Mom and Dad for having me and for Jeannie (or Jack or Debra or Donnie or …) for putting up with me so supportively and for my nine children for not interrupting me and for my Publisher for not discouraging me and for my Writers’ Circle for listening to me and for Barbie and Greta and Albert Einstein and Aunty May and so on. Ignore this, even if you are wondering if Albert Einstein is Albert Einstein or in fact the dog. This will be followed by a short piece of prose that says When the night of the wolf waxes strong in the morning, the wise man is wary of a false dawn. Ka’a Orto’o, Gnomic Utterances Ignore this too (or, if really puzzled, look up GNOMIC UTTERANCES in the Toughpick section). Find the Map. 2. Examine the Map. It will show most of a continent (and sometimes part of another) with a large number of BAYS, OFFSHORE ISLANDS, an INLAND SEA or so and a sprinkle of TOWNS. There will be scribbly snakes that are probably RIVERS, and names made of CAPITAL LETTERS in curved lines that are not quite upside down. By bending your neck sideways you will be able to see that they say things like “Ca’ea Purt’wydyn” and “Om Ce’falos.” These may be names of COUNTRIES, but since most of the Map is bare it is hard to tell. -

The Role of Critical Literacy in Challenging the Status Quo in Twentieth Century English Children’S Literature

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2018 The Role of Critical Literacy in Challenging the Status Quo in Twentieth Century English Children’s Literature Rene Fleischbein University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Fleischbein, Rene, "The Role of Critical Literacy in Challenging the Status Quo in Twentieth Century English Children’s Literature" (2018). Dissertations. 1556. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1556 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROLE OF CRITICAL LITERACY IN CHALLENGING THE STATUS QUO IN TWENTIETH CENTURY ENGLISH CHILDREN’S LITERATURE by René Elizabeth Fleischbein A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters and the Department of English at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Dr. Jameela Lares, Committee Chair Dr. Eric Tribunella Dr. Katherine Cochran Dr. Damon Franke Dr. Farah Mendlesohn ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Jameela Lares Dr. Luis Iglesias Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Department Chair Dean of the Graduate School August 2018 COPYRIGHT BY René Elizabeth Fleischbein 2018 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT Although many children’s literature critics focus on the two divides between instruction and delight and between the fantastic and the realist, this dissertation focuses on the occurrences in twentieth century English children’s fantasy of critical literacy, a mode of reading that challenges the status quo of society and gives voice to underrepresented and marginalized groups. -

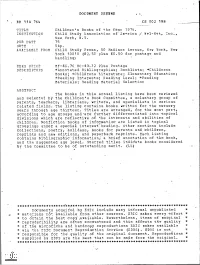

According to Age Groups Andare Further Differentiated Into Topical Documentsacguied by ERIC Include Many Informal Unpublished *

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 114 764 CS 002 198 TITLE Children's Books of the Year 1974. INSTITUTION Child Study Association of f-America / Wel-Met, Inc., New York, N.Y. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 54p. AVAILABLE FROM Child Study Press, 50 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10010 ($2.5C plus $0.50 for postage and handling) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$3.32.Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies; .Booklists; *Childrens Books; *Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; *Reading Interests; Reading Level; *Reading Materials; Reading Material Selection ABSTRACT The books in this annual listing have been reviewed and selected by the Children's Book Committee, a voluntary group of parents, teachers, librarians, writers, and specialists in various related, fields. The listing contains books written for the nursery years through age thirteen. Titles are arranged, for the most parti according to age groups andare further differentiated into topical divisiOns which are reflective of the interests and abilities of children. Nonfiction books of infOrinatiow are listed in topical groupings under a special interest heading. Other sections include collections,' poetry, holidays, books for parents and, children, reprints and new editions, and paperback reprints. Each listing, contains bibliographic information; a brief annotation of the book, and the 'suggested age level. Starred titleS indicate books considered by the Committee to be of outstanding merit. (LL) *********************,************************************************* * Documentsacguied by ERIC include many informal unpublished * .o, * materiaasnot available from other sources. EPIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy..a.vailable. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are.often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction SPrvice (EDRS) .EDRS is not * * responsible for the quality of the original document.