HAPTER 7 Fantasy, Science Fiction, Utopias, and Dystopias

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FICTIONAL NARRATIVE WRITING RUBRIC 4 3 2 1 1 Organization

FICTIONAL NARRATIVE WRITING RUBRIC 4 3 2 1 1 The plot is thoroughly Plot is adequately The plot is minimally The story lacks a developed Organization: developed. The story is developed. The story has developed. The story plot line. It is missing either a interesting and logically a clear beginning, middle does not have a clear beginning or an end. The organized: there is clear and end. The story is beginning, middle, and relationship between the exposition, rising action and arranged in logical order. end. The sequence of events is often confusing. climax. The story has a clear events is sometimes resolution or surprise confusing and may be ending. hard to follow. 2 The setting is clearly The setting is clearly The setting is identified The setting may be vague or Elements of Story: described through vivid identified with some but not clearly described. hard to identify. Setting sensory language. sensory language. It has minimal sensory language. 3 Major characters are well Major and minor Characters are minimally Main characters are lacking Elements of Story: developed through dialogue, characters are somewhat developed. They are development. They are Characters actions, and thoughts. Main developed through described rather than described rather than characters change or grow dialogue, actions, and established through established. They lack during the story. thoughts. Main dialogue, actions and individuality and do not change characters change or thoughts. They show little throughout the story. grow during the story. growth or change during the story. 4 All dialogue sounds realistic Most dialogue sounds Some dialogue sounds Dialogue may be nonexistent, Elements of Story: and advances the plot. -

Top Hugo Nominees

Top 2003 Hugo Award Nominations for Each Category There were 738 total valid nominating forms submitted Nominees not on the final ballot were not validated or checked for errors Nominations for Best Novel 621 nominating forms, 219 nominees 97 Hominids by Robert J. Sawyer (Tor) 91 The Scar by China Mieville (Macmillan; Del Rey) 88 The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson (Bantam) 72 Bones of the Earth by Michael Swanwick (Eos) 69 Kiln People by David Brin (Tor) — final ballot complete — 56 Dance for the Ivory Madonna by Don Sakers (Speed of C) 55 Ruled Britannia by Harry Turtledove NAL 43 Night Watch by Terry Pratchett (Doubleday UK; HarperCollins) 40 Diplomatic Immunity by Lois McMaster Bujold (Baen) 36 Redemption Ark by Alastair Reynolds (Gollancz; Ace) 35 The Eyre Affair by Jasper Fforde (Viking) 35 Permanence by Karl Schroeder (Tor) 34 Coyote by Allen Steele (Ace) 32 Chindi by Jack McDevitt (Ace) 32 Light by M. John Harrison (Gollancz) 32 Probability Space by Nancy Kress (Tor) Nominations for Best Novella 374 nominating forms, 65 nominees 85 Coraline by Neil Gaiman (HarperCollins) 48 “In Spirit” by Pat Forde (Analog 9/02) 47 “Bronte’s Egg” by Richard Chwedyk (F&SF 08/02) 45 “Breathmoss” by Ian R. MacLeod (Asimov’s 5/02) 41 A Year in the Linear City by Paul Di Filippo (PS Publishing) 41 “The Political Officer” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 04/02) — final ballot complete — 40 “The Potter of Bones” by Eleanor Arnason (Asimov’s 9/02) 34 “Veritas” by Robert Reed (Asimov’s 7/02) 32 “Router” by Charles Stross (Asimov’s 9/02) 31 The Human Front by Ken MacLeod (PS Publishing) 30 “Stories for Men” by John Kessel (Asimov’s 10-11/02) 30 “Unseen Demons” by Adam-Troy Castro (Analog 8/02) 29 Turquoise Days by Alastair Reynolds (Golden Gryphon) 22 “A Democracy of Trolls” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 10-11/02) 22 “Jury Service” by Charles Stross and Cory Doctorow (Sci Fiction 12/03/02) 22 “Paradises Lost” by Ursula K. -

Intimating Intimacy: Self-Shattering Intimacy in Christopher Paolini's

Intimating Intimacy: Self-Shattering Intimacy in Christopher Paolini’s Inheritance Cycle Although children’s and young adult literature often define intimacy in the context of familial and sexual relationships, intimacy encompasses so much more. Following the thoughts of Georges Bataille, intimacy shatters the self-contained individual; it changes the perception of the world. It brings people and nature into continuity. Intimacy overcomes the evil of subjugating others to the meager existence of utility. This result of intimacy becomes exceedingly important because it seeks to restore connection between people. Through dissolving the self, intimacy breaks the barriers people place around themselves, exposing them to others. This exposure breaks the cycle of disjoint individuals to shape continuity among people. The foundational movement here breaks the individual self by completely opening them to another being. Intimacy changes societal dynamics by denying the utility of others, moving beyond people as only a means to an end. People count as human beings again rather than only the service(s) they perform. In this way, intimacy brings people out of individualized self-centeredness into continuity across existence. Christopher Paolini’s Inheritance Cycle imagines intimacy as fostering a deeper connection with other forms of life. Paolini’s novels bring intimacy to the fore, creating a fantastical story of good triumphing over evil through intimacy. The intimacy of the Inheritance Cycle allows a person to see beyond the discontinuous individual self, moving to a space of continuity with the world. This understanding of intimacy follows directly from Georges Bataille’s theoretical understanding of eroticism and intimacy. This intimacy shatters the self and moves people into a space of continuity with all living things. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender Kazue Harada Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2015 Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender Kazue Harada Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the East Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Harada, Kazue, "Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender" (2015). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 442. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/442 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of East Asian Languages & Cultures Dissertation Examination Committee: Rebecca Copeland, Chair Nancy Berg Ji-Eun Lee Diane Wei Lewis Marvin Marcus Laura Miller Jamie Newhard Japanese Women’s Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender by Kazue Harada A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 St. Louis, Missouri © 2015, Kazue Harada -

Fiction As Research Practice: Short Stories, Novellas, and Novels

Alberta Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 62.1, Spring 2016, 130-133 Book Review Fiction as Research Practice: Short Stories, Novellas, and Novels Patricia Leavy Walnut, CA: Left Coast Press Inc., 2013 Reviewed by: Frances Kalu University of Calgary Fiction as Research Practice: Short Stories, Novellas, and Novels introduces the reader to fiction-based research. In the first section, Patricia Leavy explores the genre by explaining its background and possibilities and goes on to describe how to conduct and evaluate fiction-based research. In the second section of the book, she presents and evaluates examples of fiction-based research in different forms including short stories and excerpts from novellas and novels written by different authors. The third and final section explains how fiction and fiction-based research can be used in teaching. Leavy clearly differentiates the term fiction-based research from arts- based research in order to project the emergent field in a clear light of its own. Babbie (2001) explains that just as qualitative research practice emerged as a means of explaining phenomena that could not be captured by quantitative scientific research, social research attempts to study and understand everyday life experiences. Within social research, arts-based research tries to represent phenomena studied aesthetically through various forms of art (Barone & Eisner, 2012). As a form of arts-based research, Leavy describes fiction-based research as a great way to explore “topics that can be difficult to approach” through fiction (p. 20). Topics include the intricacies of interactions in everyday life, race relations, and socio-economic class and its effects on human life. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Mythcon 50 Program Book

M L o o v o i k n i g n g F o r B w a a c r k d Program Book San Diego, California • August 2-5, 2019 Mythcon 50: Moving Forward, Looking Back Guests of Honor Verlyn Flieger, Tolkien Scholar Tim Powers, Fantasy Author Conference Theme To give its far-flung membership a chance to meet, and to present papers orally with audience response, The Mythopoeic Society has been holding conferences since its early days. These began with a one-day Narnia Conference in 1969, and the first annual Mythopoeic Conference was held at the Claremont Colleges (near Los Angeles) in September, 1970. This year’s conference is the third in a series of golden anniversaries for the Society, celebrating our 50th Mythcon. Mythcon 50 Committee Lynn Maudlin – Chair Janet Brennan Croft – Papers Coordinator David Bratman – Programming Sue Dawe – Art Show Lisa Deutsch Harrigan – Treasurer Eleanor Farrell – Publications J’nae Spano – Dealers’ Room Marion VanLoo – Registration & Masquerade Josiah Riojas – Parking Runner & assistant to the Chair Venue Mythcon 50 will be at San Diego State University, with programming in the LEED Double Platinum Certified Conrad Prebys Aztec Student Union, and onsite housing in the South Campus Plaza, South Tower. Mythcon logo by Sue Dawe © 2019 Thanks to Carl Hostetter for the photo of Verlyn Flieger, and to bg Callahan, Paula DiSante, Sylvia Hunnewell, Lynn Maudlin, and many other members of the Mythopoeic Society for photos from past conferences. Printed by Windward Graphics, Phoenix, AZ 3 Verlyn Flieger Scholar Guest of Honor by David Bratman Verlyn Flieger and I became seriously acquainted when we sat across from each other at the ban- quet of the Tolkien Centenary Conference in 1992. -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

Science Fiction Review 29 Geis 1979-01

JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1979 NUMBER 29 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $1.50 NOISE LEVEL By John Brunner Interviews: JOHN BRUNNER MICHAEL MOORCOCK HANK STINE Orson Scott Card - Charles Platt - Darrell Schweitzer Elton Elliott - Bill Warren SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC RO. Bex 11408 COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN January, 1979 — Vol .8, No.l Based on a forthcoming novel, SIVA, Portland, OR WHOLE NUMBER 29 by Leigh Richmond 97211 ALIEN TOUTS......................................3 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & piblisher SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION INTERVIEW WITH JOHN BRUWER............. 8 PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY CONDUCTED BY IAN COVELL PAGE 63 JAN., MARCH, MAY, JULY, SEPT., NOV. NOISE LEVEL......................................... 15 SINGLE COPY ---- $1.50 A COLUMN BY JOHN BRUNNER REVIEWS-------------------------------------------- INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL MOORCOCK.. .18 PHOfC: (503) 282-0381 CONDUCTED BY IAN COVELL "seasoning" asimov's (sept-oct)...27 "swanilda 's song" analog (oct)....27 THE REVIEW OF SHORT FICTION........... 27 "LITTLE GOETHE F&SF (NOV)........28 BY ORSON SCOTT CARD MARCHERS OF VALHALLA..............................97 "the wind from a burning WOMAN ...28 SKULL-FACE....................................................97 "hunter's moon" analog (nov).....28 SON OF THE WHITE WOLF........................... 97 OCCASIONALLY TENTIONING "TUNNELS OF THE MINDS GALILEO 10.28 SWORDS OF SHAHRAZAR................................97 SCIENCE FICTION................................ 31 "the incredible living man BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER BLACK CANAAN........................................ -

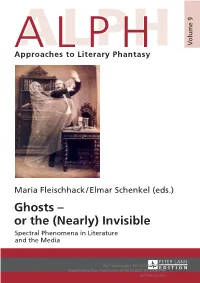

Ghosts – Or the (Nearly) Invisible

9 In this volume, ghost stories are studied in the context of their media, their place in history and geography. From prehistory to this day, we have been haunted by our memories, the past itself, by inklings of the future, by events playing outside our lives, and by ourselves. Hence the lure of ghost stories throughout history 9 Volume and presumably prehistory. Science has been a great destroyer of myth and superstition, but at the same time it has created new black boxes which we are ALPHALPH Approaches to Literary Phantasy filling with our ghostly imagination. In this book, literature from the Middle Ages to Oscar Wilde and Neil Gaiman, children’s stories, folklore and films, ranging from the Antarctic and Russia to Haiti, are covered and show the continuing presence of spectral phenomena. Maria Fleischhack / Elmar Schenkel (eds.) Elmar Schenkel (eds.) · Ghosts – or the (Nearly) Invisible / Ghosts – Maria Fleischhack lectures at Leipzig University with a focus on Victorian and Postmodern fiction and Shakespearean drama; special interest: Sherlock or the (Nearly) Invisible Holmes. Elmar Schenkel teaches English Literature at the University of Leipzig. He has Spectral Phenomena in Literature published on Wells, Conrad and Tolkien and the relations between science and the Media and literature. Maria Fleischhack ISBN 978-3-631-66566-4 Guy Tourlamain - 978-3-0353-9996-7 Downloaded from PubFactory at 09/23/2021 02:26:57PM via free access ALPH 09_266566_Fleischhack_gr_HCA5_Eng PLE.indd 1 28.06.16 KW 26 14:24 9 In this volume, ghost stories are studied in the context of their media, their place in history and geography.