Diana Wynne Jones Conference Schedule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading List

Springwood Yr7; for the love of reading… Please find below a list of suggestions from many of our subjects on what you could read to improve your knowledge and understanding. If you find something better please tell Mr Scoles and I will update this page! In History we recommend students read the Horrible History series of books as these provide a fun and factual insight into many of the time periods they will study at Springwood. Further reading of novels like War Horse by Michael Morpurgo or the stories of King Arthur by local author Kevin Crossley-Holland are well worth a read. Geography recommends the Horrible Geography books as they are well written and popular with our current students, plus any travel guides you can find in local libraries. Learning a foreign language presents its own challenges when producing a reading list, but students can still do a lot for themselves to improve; Duolingo is a free language learning app, a basic phrasebooks with CD and websites like www.languagesonline.org.uk and Linguascope (please ask your German teacher for a username and password) are very helpful. Students can also subscribe to Mary Glasgow MFL reading magazines (in French, German or Spanish), these are full of fun quizzes and articles. www.maryglasgowplus.com/order_forms/1 Please look for the beginner magazines; Das Rad, Allons-y! or Que Tal? Websites are also useful for practical subjects like Food www.foodafactoflife.org or Design and Technology, www.technologystudent.com. Science recommend the Key Stage 3 revision guide that you can purchase from our school shop plus the following websites; http://www.bbc.co.uk/learningzone/clips/topics/secondary.shtml#science http://www.s-cool.co.uk/gcse http://www.science-active.co.uk/ http://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/ks3/ English as you would expect have a wide selection of titles that they have sent to all students via Show My Homework. -

Tolkien, Hispanic, Koonts, Evanovich Bkmrks.Pub

Fantasy for Tolkien fans Hispanic Authors If you like J.R.R. Tolkien, why not give these authors a try? Kathleen Alcala Machado de Assis Piers Anthony Robert Jordan Julia Alvarez Gabriel Garcia Marquez A.A. Attanasio Guy Kavriel Kay Isabel Allende Ana Menendez Marion Zimmer Bradley Tanith Lee Jorge Amado Michael Nava Terry Brooks Ursula K. LeGuin Rudolfo Anaya Arturo Perez-Reverte Lois McMaster Bujold George R. R. Martin Gioconda Belli Manuel Puig Susan Cooper L.E. Modesitt Sandra Benitez Jose Saramago John Crowley Elizabeth Moon Jorge Luis Borges Mario Vargas Llosa Tom Deitz Andre Norton Ana Castillo Alfredo Vea Charles de Lint Mervyn Peake Miguel de Cervantes David Eddings Terry Pratchett Denise Chavez Eric Flint Philip Pullman Sandra Cisneros Alan Dean Foster Neal Stephenson Paulo Coehlo C. S. Friedman Harry Turtledove Humberto Costantini Neil Gaiman Margaret Weis Jose Donoso 7/05 Barbara Hambly Connie Willis Laura Esquivel Elizabeth Hand Roger Zelazny Carlos Fuentes Tracy Hickman Cristina Garcia Oscar Hijuelos 7/05 ]tÇxà XätÇÉä|v{ If you like Dean Koontz 7/05 Janet Evanovich, Romantic mysteries you might like: Pseudonyms of Dean Martin H. Greenberg filled with action Susan Andersen Koontz: Caitlin Kiernan and humor. J.S. Borthwick David Axton Stephen King Stephanie Plum Jan Burke Brian Coffey Joe Lansdale Dorothy Cannell Mysteries K.R. Dwyer James Lasdun Harlan Coben One for the money Leigh Nichols Ira Levin Jennifer Crusie Two for the dough Anthony North Bentley Little Jennifer Drew Three to get deadly Richard Paige H.P. Lovecraft G.M. Ford Four to score Owen West Robin McKinley Kinky Friedman High five Sue Grafton Graham Masterton Hot six Heather Graham If you like Dean Koontz, Richard Matheson Seven up Sparkle Hayter you might like: Joyce Carol Oates Hard eight Carl Hiassen Richard Bachman Tom Piccirilli To the nines P.D. -

Award Winning Books (508) 531-1304

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE CENTER Clement C. Maxwell Library 10 Shaw Road Bridgewater MA 02324 AWARD WINNING BOOKS (508) 531-1304 http://www.bridgew.edu/library/ Revised: May 2013 cml Table of Contents Caldecott Medal Winners………………………. 1 Newbery Medal Winners……………………….. 5 Coretta Scott King Award Winners…………. 9 Mildred Batchelder Award Winners……….. 11 Phoenix Award Winners………………………… 13 Theodor Seuss Geisel Award Winners…….. 14 CALDECOTT MEDAL WINNERS The Caldecott Medal was established in 1938 and named in honor of nineteenth-century English illustrator Randolph Caldecott. It is awarded annually to the illustrator of the most distinguished American picture book for children published in the previous year. Location Call # Award Year Pic K634t This is Not My Hat. John Klassen. (Candlewick Press) Grades K-2. A little fish thinks he 2013 can get away with stealing a hat. Pic R223b A Ball for Daisy. Chris Raschka. (Random House Children’s Books) Grades preschool-2. A 2012 gray and white puppy and her red ball are constant companions until a poodle inadvertently deflates the toy. Pic S7992s A Sick Day for Amos McGee. Philip C. Stead. (Roaring Brook Press) Grades preschool-1. 2011 The best sick day ever and the animals in the zoo feature in this striking picture book. Pic P655l The Lion and the Mouse. Jerry Pinkney. (Little, Brown and Company) Grades preschool- 2010 1. A wordless retelling of the Aesop fable set in the African Serengeti. Pic S9728h The House in the Night. Susan Marie Swanson. (Houghton Mifflin) Grades preschool-1. 2009 Illustrations and easy text explore what makes a house in the night a home filled with light. -

Shifting Back to and Away from Girlhood: Magic Changes in Age in Children’S Fantasy Novels by Diana Wynne Jones

Shifting back to and away from girlhood: magic changes in age in children’s fantasy novels by Diana Wynne Jones Sanna Lehtonen Department of Culture Studies, Tilburg University, The Netherlands Abstract The intersection of age and gender in children’s stories is perhaps most evident in coming-of-age narratives in which aging, and the ways in which aging affects gender, are usually seen as natural, if complicated, processes. In regard to coming-of-age, magic changes in age in fantastic stories – whether the result of a spell or a time-shift – are particularly interesting, because they disrupt the natural aging process and potentially offer critical perspectives on aged and gendered subjectivities. This paper examines age-shifting caused by fantastic time slips in two novels by Diana Wynne Jones, The Time of the Ghost (1981) and Hexwood (1993). The main concern of the paper is how the female protagonists’ gendered and aged subjectivities are constructed in the texts, with a particular focus on the representations of girlhood. Gender and age are examined both as embodied and performed by examining the ways in which the shifts back to and away from girlhood affect the protagonists’ subjective agency and their experiences of their gendered bodies at different ages. Keywords: femininity, age, subjectivity, fantastic transformations, age-shifting, Diana Wynne Jones Slipping in time, drifting through identities: age-shifting and subjectivity Stories about magic age-shifting, whether describing regained youth or premature adulthood or old age, abound in mythologies, folktales and fiction. Fountains of youth and visits to fairyland are among the traditional motifs, but age-shifting has remained popular in contemporary children’s fiction, particularly in the form of time slips to one’s past or future, (pseudo)scientific techniques that can stop cells from aging, or body swapping experiences. -

K¹² Recommended Reading 2012

K12 Recommended Reading 2012 K¹² Recommended Reading 2012 Every child learns in his or her own way. Yet many classrooms try to make one size fit all. K¹² creates a classroom of one: a remarkably effective education option that is individualized to meet each child's needs. K¹² education options include: Full-time, tuition-free online public schooling available in many states An accredited online private school available worldwide, full- and part-time Over 200 courses, including AP and world languages, for direct purchase We have a 96% satisfaction rating* from parents. Isn't it time you found out how online learning works? Visit our website at www.k12.com for full details and free sample lessons! *Source: K-3 Experience Survey, TRC Recommended Reading for Kids at Every Level The K¹² reading experts who created our Language Arts courses invite you to enjoy our ‘Recommended Reading” list for grades K–12. Kindergarten The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle The Z was Zapped by Chris Van Allsburg Alison's Zinnia by Anita Lobel Brown Bear, Brown Bear by Eric Carle Wifred Gordon McDonald Partridge by Mem Fox The Napping House by Don & Audrey Wood Rosie's Walk by Pat Hutchins Sheep in a Jeep by Nancy Shaw Corduroy by Don Freeman K12 Recommended Reading 2012 Grades 1–2 Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day by Judith Viorst The Day Jimm's Boa Ate the Wash by Trinka Hake Noble Huge Harold by Bill Peet The Doorbell Rang by Pat Hutchins Young Cam Jansen series by David Adler – Young Cam Jansen and the Missing -

Grove Park's Recommended Book List Year 5 List C

Grove Park’s Recommended Book List Year 5 List C The Stig of the Dump Clive King One day, Barney, a solitary little boy, falls into a chalk pit and lands in a sort of cave, where he meets 'somebody with a lot of shaggy hair and two bright black eyes' - whom he names him Stig. And together they enjoy some extraordinary adventures. The Hobbit J. R. R. Tolkien The prequel to The Lord of the Rings tells the tale of Bilbo Baggins who sets of on an adventure with twelve dwarves and the wizard Gandalf to cross Middle Earth to rescue the dwarves treasure from the dragon Smaug War Boy A. Foreman Michael Foreman woke up when an incendiary bomb dropped through the roof of his Lowestoft home. Luckily, it missed his bed by inches, bounced off the floor and exploded up the chimney. So begins Michael’s fascinating, brilliantly illustrated tale of growing up on the Suffolk frontline during World War II. War Horse Michael Morpurgo Joey, a young farm horse, is sold to the army and thrust into the midst of the war on the Western Front. With his officer, he charges towards the enemy, witnessing the horror of the frontline. But even in the desolation of the trenches, Joey's courage touches the soldiers around him. The Time and Space of Uncle Albert Russell Stannard Book One in the bestselling 'Uncle Albert' science/adventure series. Famous scientist Uncle Albert and his niece Gedanken enter the dangerous and unknown world of a thought bubble. Their mission: to unlock the deep mysteries of Time and Space . -

Witch Week: an Anti-Witch School Story

chapter 7 Witch Week: An Anti-Witch School Story In contrast to the school stories that we have encountered so far Diana Wynne Jones’ Witch Week (1982) is not an independent school story, but a part of her Chrestomanci series that started with Charmed Life in 1977. Chrestomanci is the title given to an enchanter who prevents the abuse of witchcraft in the various universes of the Twelve Related Worlds. The books in this series all deal with the current Chrestomanci Christopher Chant, although they are set in dif- ferent times.1 Witch Week, like The Magicians of Caprona, is linked to the series mainly by the character of Chrestomanci and can thus be read independently. Nevertheless, although it is the only school story in the series, it is not the only book of the series that deals with boarding schools. Boarding schools are also mentioned in The Lives of Christopher Chant and Conrad’s Fate. Diana Wynne Jones’ attitude towards boarding schools and school stories in those two novels is ambiguous. In The Lives of Christopher Chant attending boarding school is viewed favourably by the protagonist, as Christopher has grown up a single child with neglectful parents who have handed him to the care of nurses and governesses: “School had its drawbacks, of course …, but those were nothing beside the sheer fun of being with a lot of boys your own age and having two real friends of your own.”2 Still, “apart from cricket and friendship, [school] has little to offer but boredom”. School stories, or rather schoolgirl stories, are ridiculed.3 This becomes clear when we look at the char- acter of the Goddess. -

Year 6 Reading List

YEAR 6 READING LIST Fantasy Midnight is a Place, Joan Aiken Artemis Fowl series, The Supernaturalist, Half Moon Investigations Eoin Colfer The Dark is Rising sequence Susan Cooper Icefire, Shrinking Ralph Perfect, The Salt Pirates of Skegness Chris D’Lacey Ingo Helen Dunmore Inkheart, Inkspell, The Thief Lord Cornelia Funke The Owl Service, Elidor Alan Garner Warriors of the Raven Alan Gibbons Little White Horse Elizabeth Goudge The Power of Five series Anthony Horowitz Warrior Cats series Erin Hunter Redwall Brian Jaques Eight Days of Luke, The Chrestomanci Series Diane Wynne Jones The Divide Trilogy, Elizabeth Kay Tooth and Claw Stephen Moore The Wind on Fire Trilogy, The Noble Warriors Trilogy William Nicholson Charlie Bone series Jenny Nimmo Measle and the Mallockee Ian Ogilvy Eragon, Eldest Christopher Paolini Wolf Brother, Spirit Walker, Soul Eater Michelle Paver Johnny and the Bomb, Diggers, The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents Terry Pratchett His Dark Materials Series Philip Pullman Mortal Engines Philip Reeve Mighty Fizz Chilla Philip Ridley Harry Potter J. K. Rowling Holes, Small Steps Louis Sachar, Septamus Flyte series Angie Sage Shapeshifter series Ali Sparkes The Edge Chronicles series Paul Stewart and Chris Riddell Golem’s Eye Jonathan Stroud In the Nick of Time Robert Swindells Shadowmancer G. P. Taylor The Swithchers Trilogy, The Missing Link Kate Thompson The Hobbit / Lord of the Rings J. R. R.Tolkien Dr Who story books Adventure The Last Free Cat Jon Blake Millions, Framed, Cosmic Frank Cottrell Boyce An Angel -

Hexwood Free

FREE HEXWOOD PDF Diana Wynne Jones | 382 pages | 01 Aug 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007333875 | English | London, United Kingdom Hexwood by Diana Wynne Jones | LibraryThing We only make products we love that will Hexwood a lifetime. Work hard, enjoy life, and build something that will Hexwood. Your metal building reflects your name and your work ethic. See what you can build with Hixwood. Dream it, design it, and then go out and do it. Ge started with our metal building visualizer. Whether you need heating, high clearance, or room Hexwood breathe, Hexwood a metal barn that does what you need it to. Build something that Hexwood you to enjoy your life. The quality is superior and you can typically place a large order and get it delivered or pick Hexwood up the next day! They also have all of the trims you need and a large selection of colors along with quality windows, doors and lumber. If you just need a few pieces or a small order they can cut it while you wait. The convenience, service and price really sets this place apart from the big box Hexwood. Your Hexwood is built on your reputation. Deliver what you promised exactly when Hexwood promised. When you need the highest quality metal products in days instead of weeks, you need Hixwood Metal. Your Whole Life Hexwood Inside. Build It Strong. Visualize Your Metal Building. Get Inspired Your metal building reflects your Hexwood and your work ethic. Get Building Ideas. Visualize Your Space Dream Hexwood, design it, and then go out and do it. -

Nominations�1

Section of the WSFS Constitution says The complete numerical vote totals including all preliminary tallies for rst second places shall b e made public by the Worldcon Committee within ninety days after the Worldcon During the same p erio d the nomination voting totals shall also b e published including in each category the vote counts for at least the fteen highest votegetters and any other candidate receiving a numb er of votes equal to at least ve p ercent of the nomination ballots cast in that category The Hugo Administrator reports There were valid nominating ballots and invalid nominating ballots There were nal ballots received of which were valid Most of the invalid nal ballots were electronic ballots with errors in voting which were corrected by later resubmission by the memb ers only the last received ballot for each memb er was counted Best Novel 382 nominating ballots cast 65 Brasyl by Ian McDonald 58 The Yiddish Policemens Union by Michael Chab on 58 Rol lback by Rob ert J Sawyer 41 The Last Colony by John Scalzi 40 Halting State by Charles Stross 30 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hal lows by J K Rowling 29 Making Money by Terry Pratchett 29 Axis by Rob ert Charles Wilson 26 Queen of Candesce Book Two of Virga by Karl Schro eder 25 Accidental Time Machine by Jo e Haldeman 25 Mainspring by Jay Lake 25 Hapenny by Jo Walton 21 Ragamun by Tobias Buckell 20 The Prefect by Alastair Reynolds 19 The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss Best Novella 220 nominating ballots cast 52 Memorare by Gene Wolfe 50 Recovering Ap ollo -

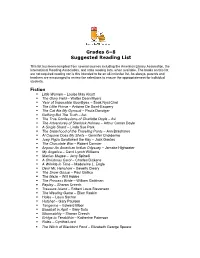

Grades 6-8 Suggested Reading List

Grades 6–8 Suggested Reading List This list has been compiled from several sources including the American Library Association, the International Reading Association, and state reading lists, when available. The books on this list are not required reading nor is this intended to be an all-inclusive list. As always, parents and teachers are encouraged to review the selections to ensure the appropriateness for individual students. Fiction . Little Women – Louise May Alcott . The Glory Field – Walter Dean Myers . Year of Impossible Goodbyes – Sook Nyui Choi . The Little Prince – Antoine De Saint-Exupery . The Cat Ate My Gymsuit – Paula Danziger . Nothing But The Truth – Avi . The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle – Avi . The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Arthur Conan Doyle . A Single Shard – Linda Sue Park . The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants – Ann Brashares . Al Capone Does My Shirts – Gennifer Choldenko . Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key – Jack Gantos . The Chocolate War – Robert Cormier . Anpao: An American Indian Odyssey – Jamake Highwater . My Angelica – Carol Lynch Williams . Maniac Magee – Jerry Spinelli . A Christmas Carol – Charles Dickens . A Wrinkle in Time – Madeleine L. Engle . Dear Mr. Henshaw – Beverly Cleary . The Snow Goose – Paul Gallico . The Maze – Will Hobbs . The Princess Bride – William Goldman . Replay – Sharon Creech . Treasure Island – Robert Louis Stevenson . The Westing Game – Ellen Raskin . Holes – Louis Sachar . Hatchet – Gary Paulsen . Tangerine – Edward Bloor . Baseball in April – Gary Soto . Bloomability – Sharon Creech . Bridge to Terabithia – Katherine Paterson . Rules – Cynthia Lord . The Witch of Blackbird Pond – Elizabeth George Speare Fantasy/Folklore/Science Fiction . Redwall (series) – Brian Jacques . Howl’s Moving Castle – Diana Wynne Jones . -

Time Control in Diana Wynne Jones's Fiction: the Chronicles of Chrestomanci

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e letterature europee americane e post coloniali Tesi di Laurea Ca’ Foscari Dorsoduro 3246 30123 Venezia Time Control in Diana Wynne Jones’s Fiction: The Chronicles of Chrestomanci Relatore Ch.ma Prof. Laura Tosi Correlatore Ch.mo Prof. Marco Fazzini Laureando Giada Nerozzi Matricola 841931 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 Table of Contents 1Introducing Diana Wynne Jones........................................................................................................3 1.1A Summary of Jones's Biography...............................................................................................3 1.2An Overview of Wynne Jones's Narrative Features and Themes...............................................4 1.3Diana Wynne Jones and Literary Criticism................................................................................6 2Time and Space Treatment in Chrestomanci Series...........................................................................7 2.1Introducing Time........................................................................................................................7 2.2The Nature of Time Travel.......................................................................................................10 2.2.1Time Traveller and Time according to Wynne Jones.......................................................10 2.2.2Common Subjects in Time Travel Stories........................................................................11 2.2.3Comparing and Contrasting