Shear-David.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operational Review of the Record Flood in Niamey, Niger

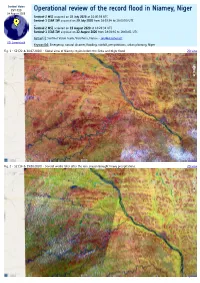

Sentinel Vision EVT-719 Operational review of the record flood in Niamey, Niger 24 August 2020 Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 22 July 2020 at 10:05:59 UTC Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 29 July 2020 from 18:03:34 to 18:03:59 UTC ... Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 19 August 2020 at 10:20:31 UTC Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 22 August 2020 from 18:03:36 to 18:04:01 UTC Author(s): Sentinel Vision team, VisioTerra, France - [email protected] 2D Layerstack Keyword(s): Emergency, natural disaster, flooding, rainfall, precipitations, urban planning, Niger Fig. 1 - S2 (22 & 30.07.2020) - Global view of Niamey region before the Sirba and Niger flood. 2D view Fig. 2 - S2 (16 & 19.08.2020) - Several weeks later after the rain season brought heavy precipitations. 2D view / Based in Niger, the local early warning system for Sirba floods (Système Local d’Alerte Précoce pour les Inondations de la Sirba, SLAPIS) reported: In Niamey, following the rainfall received in the south-western part of Niger and Burkina Faso, the water level observed at the hydrometric station of Niamey rose to 650 cm on 18/08/2020 at 09:00. This is a water level never reached in the past. Sandbags were placed on the dyke downstream of the Kennedy Bridge to prevent the water from overflowing it. Left: Hydrological stations network of the Niger river basin - Source: Niger Basin Authority Right: Cumulative precipitation in the Niger river basin over the past 3 dekads [mm] - Source: Niger Basin Authority Fig. -

Recent Changes in Hydroclimatic Patterns Over Medium Niger River Basins at the Origin of the 2020 Flood in Niamey (Niger)

water Article Recent Changes in Hydroclimatic Patterns over Medium Niger River Basins at the Origin of the 2020 Flood in Niamey (Niger) Giovanni Massazza 1,2 , Maurizio Bacci 3 , Luc Descroix 4, Mohamed Housseini Ibrahim 5, Edoardo Fiorillo 3 , Gaptia Lawan Katiellou 6, Geremy Panthou 7 , Alessandro Pezzoli 1, Maurizio Rosso 8 , Elisa Sauzedde 7, Andrea Terenziani 1, Tiziana De Filippis 3 , Leandro Rocchi 3 , Sara Burrone 3 , Maurizio Tiepolo 1 , Théo Vischel 7 and Vieri Tarchiani 3,* 1 Dipartimento Interateneo di Scienze, Progetto e Politiche del Territorio (DIST), Politecnico di Torino & Università di Torino, 10129 Torino, Italy; [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (A.T.); [email protected] (M.T.) 2 Agenzia Interregionale per Il Fiume Po (AIPo), 10024 Moncalieri, Italy 3 Istituto per la BioEconomia–Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (IBE-CNR), 50019 Sesto Fiorentino, Italy; [email protected] (M.B.); edoardo.fi[email protected] (E.F.); tiziana.defi[email protected] (T.D.F.); [email protected] (L.R.); [email protected] (S.B.) 4 Unité Mixte de Recherche Patrimoines Locaux, Environnement & Globalisation (PALOC), Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), Sorbonne Université, 75231 Paris, France; [email protected] 5 Direction de l’Hydrologie (DH), Ministère de l’Hydraulique et de l’Assainissement du Niger, Niamey 8004, Niger; [email protected] 6 Direction de la Météorologie -

Table of Contents

NIGER COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Mercer Cook 1961-1964 Ambassador, Niger Cecil S. Richardson 1962-1965 Economic Officer, Niamey Robert J. Ryan Sr. 1964-1968 Ambassador, Niger Richard S. Thompson 1965-1967 Economic Officer, Niamey Samuel C. Adams Jr. 1968-1969 Ambassador, Niger John A. Buche 1973-1975 Deputy Chief of Mission, Niamey Wayne White 1974-1976 General Service Officer/Consular Officer, Niamey Ernestine S. Heck 1974-1976 Wife of the Ambassador, Niamey Joseph C. Wilson IV 1976-1978 General Services Officer, Niamey Walter J. Sherwin 1977-1979 Program Officer, USAID, Niamey Richard C. Howland 1978 Office of the Inspector General, Washington, DC Harvey E. Gutman 1978-1979 Program Officer, USAID, Niamey Susan Keogh 1978-1980 Spouse of Deputy Chief of Mission, Niamey E. Michael Southwick 1982-1985 Deputy Chief of Mission, Niamey Albert E. Fairchild 1985-1987 Deputy Chief of Mission, Niamey Richard W. Bogosian 1985-1988 Ambassador, Niger Carl C. Cundiff 1988-1991 Ambassador, Niger Claudia Anyaso 1990-1993 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Niamey Charles O. Cecil 1996-1999 Ambassador, Niger 1 MERCER COOK Ambassador Niger (1961-1964) Ambassador Cook was born and raised in Washington D.C. and educated at Amherst College and the Universities of Paris and Brown. During his career as a professor of romance languages, the Ambassador served on the faculties of Atlanta University, the University of Haiti and Howard University. In 1961 he was appointed US Ambassador to Niger, where he served until May, 1964. That year he was appointed Ambassador to Senegal and Gambia, residing at Dakar, where he served until July, 1966. -

E6978b8c6f842788485463a7e1

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Planning to cope with tropical and subtropical climate change Original Planning to cope with tropical and subtropical climate change / Tiepolo, Maurizio; Ponte, Enrico; Cristofori, ELENA ISOTTA. - STAMPA. - Libro pubblicato sia in formato cartaceo che elettronico open access (DOI: 10.1515/9783110480795, e-ISBN 978-3-11-048079-5).(2016), pp. 1-380. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2624919 since: 2017-05-04T12:04:59Z Publisher: De Gruyter Open Ltd Published DOI: Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 17 December 2018 OPEN PLANNING TO COPE WITH TROPICAL AND SUBTROPICAL CLIMATE CHANGE CHANGE CLIMATE WITHTROPICALANDSUBTROPICAL COPE PLANNING TO EnricoPonte,ElenaCristofori Maurizio Tiepolo, Maurizio Tiepolo, Enrico Ponte, Elena Cristofori (Eds.) During the last decade, many local governments have launched initiatives to reduce CO2 emissions and the potential impact of hydro-climatic disasters. Nonetheless, PLANNING TO COPE today barely 11% of subtropical and tropical cities with over 100,000 inhabitants have a climate plan. Often this tool neither issues from an analysis of climate change or hydro climatic risks, nor does it provide an adequate depth of detail WITH TROPICAL for the identified measures (cost, funding mode, implementation), nor a sound monitoring-evaluation device. This book aims to improve the quality of climate planning by providing 19 examples AND SUBTROPICAL of analysis and assessments in eleven countries. It is intended for local operators in the fields of climate, hydro-climatic risks, physical planning, besides researchers and students of these subjects. -

Sahelian Land-Cover Degradation and Its Effects on the Silting-Up of the Middle Niger River Okechukwu Amogu

Sahelian land-cover degradation and its effects on the silting-up of the middle Niger River Okechukwu Amogu To cite this version: Okechukwu Amogu. Sahelian land-cover degradation and its effects on the silting-up of the middle Niger River. Hydrology. Université Joseph-Fourier - Grenoble I, 2009. English. tel-00385629v1 HAL Id: tel-00385629 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00385629v1 Submitted on 19 May 2009 (v1), last revised 19 May 2009 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Joseph Fourier Grenoble 1 THESE présentée et soutenue publiquement par Okechukwu AMOGU pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE JOSEPH FOURIER GRENOBLE 1 Spécialité : Océan, Atmosphère, Hydrologie préparée au Laboratoire d’étude des Transferts en Hydrologie et Environnement (LTHE, UMR 5564, CNRS-INPG-IRD-UJF) dans le cadre de l’Ecole Doctorale : Terre, Univers, Environnement La dégradation des espaces sahéliens et ses conséquences sur l'alluvionnement du fleuve Niger moyen Date de soutenance : 4 Mai 2009 Composition du jury : Mr Gil Mahé -

Beyond Ethnicity: African Protests in an Age of Inequality

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Beyond Ethnicity: African Protests in an Age of Inequality A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Lisa Michele Mueller 2014 c Copyright by Lisa Mueller 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Beyond Ethnicity: African Protests in an Age of Inequality by Lisa Michele Mueller Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Miriam Golden, Chair What explains African protests in an age of rising prosperity? I show that the main cause of the increasingly frequent urban protests that we observe in twenty-first century Africa is economic inequality despite substantial economic growth. Using cross-national statistical analyses of most African countries and original ethnographic and individual-level survey data from fieldwork in Niger, I find that African protests are driven largely by economic or material con- cerns, and less by ethnic antipathies or preferences for democracy. Examining different forms of inequality and grievance, I show that Africans are more likely to protest, all else equal, if they perceive their future economic opportunities as constricting instead of expanding. Economic or material concerns, however, are not sufficient to cause protest participation. Corroborating other scholars' research, I also find that social networks are important for mobilizing aggrieved people by providing solutions for coordination and cooperation problems. ii This dissertation of Lisa Michele Mueller is approved. Pierre Englebert Edmond Keller Daniel Posner Miriam Golden, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2014 iii Contents I Introduction 1 1 Prosperity and Protest in Africa 2 1.1 Does Ethnicity Cause Conflict in Africa? . -

Southern Songhay Speech Varieties in Niger

Southern Songhay Speech Varieties In Niger A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Zarma, Songhay, Kurtey, Wogo, and Dendi Peoples of Niger Performed by Byron & Annette Harrison and Michael J. Rueck with Mahaman Soumana as Interpreter January - March 1997 Report Drafted by Byron & Annette Harrison and Michael J. Rueck Summer Institute of Linguistics B.P. 10151, Niamey, Niger Republic December 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS 0 Introduction and goals of the survey......................................................... 1 0.1 Reason for undertaking the survey................................................................................................. 1 0.2 Research questions......................................................................................................................... 1 1 General information .................................................................................... 1 1.1 Language name, classification and location................................................................................... 1 Map 1 Carte des dialectes de la langue Soay .............................................................................. 3 1.2 Population ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Table 1.2 Populations of speakers of Southern Songhay dialects................................................. 4 1.3 Accessibility and transport............................................................................................................ -

West African Journal: a Travel Account

A/I WEST AFRICAN JOURNAL: A TRAVEL ACCOUNT THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Jacquelyn Fuller Hudson, B. A. Denton, Texas December, 1980 Hudson, Jacquelyn Fuller, West African Journal: A Travel Account. Master of Arts (English), December, 1980, 368 pp.. West African Journal: A Travel Account is a narrative of the author's trip in twelve West African countries. In the first chapter the author describes her previous travels and preparations for this trip and introduces her husband. She begins the second chapter with a dis- cussion of the benefits and hardships of independent travel and describes the hotels, restaurants, forms of transportation, and difficulties with language. The re- mainder of Chapter II is a close account of the first sixteen days of travel. The narrative continues chronologically in Chapters III through VIII. Each chapter pertains to a distinct stage of the trip. In Chapter IX, the author reviews her personal accomplishments during the journey, relates her and her husband's reactions on their return to the U.S., and concludes with some evocative descriptions of West Africa. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION II. IVORY COAST AND GHANA . 19 III. TOGO AND UPPER VOLTA . .r . 93 .139... IV. MALI AND SENEGAL . ..". .216... V. SIERRA LEONE AND LIBERIA . .282 VI. RETURN TO MALI . 314.... VII. NIGER AND BENIN.. .. .333... VIII. CAMEROON . .360... IX. CONCLUSION . 0... iii * c- IL2 1 1 42J C- r- C- C\- -) tJ It -- - - I f ho - fN .< Y. -

Sahelian Land-Cover Degradation and Its Effects on the Silting-Up of the Middle Niger River Okechukwu Amogu

Sahelian land-cover degradation and its effects on the silting-up of the middle Niger River Okechukwu Amogu To cite this version: Okechukwu Amogu. Sahelian land-cover degradation and its effects on the silting-up of the middle Niger River. Hydrology. Université Joseph-Fourier - Grenoble I, 2009. English. tel-00385629v2 HAL Id: tel-00385629 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00385629v2 Submitted on 19 May 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Joseph Fourier Grenoble 1 THESE présentée et soutenue publiquement par Okechukwu AMOGU pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE JOSEPH FOURIER GRENOBLE 1 Spécialité : Océan, Atmosphère, Hydrologie préparée au Laboratoire d’étude des Transferts en Hydrologie et Environnement (LTHE, UMR 5564, CNRS-INPG-IRD-UJF) dans le cadre de l’Ecole Doctorale : Terre, Univers, Environnement La dégradation des espaces sahéliens et ses conséquences sur l'alluvionnement du fleuve Niger moyen Date de soutenance : 4 Mai 2009 Composition du jury : Mr Gil Mahé Directeur de Recherche, IRD Montpellier -

World Bank Document

R ESTR I CTE D> Report No. AW-36a This report is for official use only by the Barnk Group and specifically authorized organizations Public Disclosure Authorized or persons. It may not be published, quoted or cited without Bank Group authorization. The Bank Group does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or cornpleteness of the report. INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Public Disclosure Authorized ECONOMIC POSITION AND PROSPECTS OF NIGER Public Disclosure Authorized May, 1972 Public Disclosure Authorized Western Africa Department CURRENCY EQIALENTS (a) Urntil August 11, 1969 US:$ 1.00 CFAF 246-85 French Franc 1.00 = CFAF 50.00 (b) After Agust 11, 1969 US$ 1.00 CFAF 277.71 French Franc 1.00 GCFAF 50.00 This report is based on the findings of a mission which visited Niger in March 1970. The mission was composed of the following members: H. Sânger Chief - General Economist G. Fossi Planning Officer U. Fontana Agriculturist (PMWA) A. I}uncan Transportation Erngineer (PNWA) H. Ochs Agricul-bural Economist A. Robinet Livestock Specialist - Consultant FAC NIGER TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. BASIC DATA IAPS SUMMARY AND CONSLUSIONS .................................... i - x Ie GENERAL BACKGROUND - CONSTRAINTS ON DEVELOPMENT ............... 1 A. Natural Resources ..................................... 1 Climate and Soils .................................... 1 Minerals ............................................. 2 B. Human Resources ...................................... 3 Population and -

United States Foreign Assistance Oral History Program

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Assistance Series ANTHONY MILES SCHWARZWALDER Interviewed by: William Haven North Initial interview date: December 27, 1997 Copyright 2018 ADST The oral history program was made possible through support provided by the Center for Development Information and Evaluation, U.S. Agency for International Development, under terms of Cooperative Agreement No. AEP-0085-A-00-5026-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Arlington Virginia 1940 Bachelor of Arts in Government from Wesleyan University 1957-1961 Master of Public Health from John Hopkins University 1976-1977 Joined USAID 1978 Washington, DC—Desk Officer 1961-1966 Development Loan Fund Merging with ICA Work in Guinea and the Volta River Dam Amman, Jordan—Loan Officer 1966-1968 Arab-Israeli War The East Ghor Canal Studied International Affairs at Princeton University 1968-1969 Islamabad, Pakistan—First Director of Office of Relief and Rehabilitation 1969-1974 Regional Economic Development Services Office (REDSO) Rebuilding after the 1970 Bangladesh Cyclone Rebuilding after the Bangladesh War of Independence Almost Ending the Program over Cuba Trade Camilla Program 1 Washington, DC, Bureau for Near East—Director of NE/NENA 1974-1976 Helmand Valley Project New Directions in the Agency Studied -

2016 Country Review

Niger 2016 Country Review http://www.countrywatch.com Table of Contents Chapter 1 1 Country Overview 1 Country Overview 2 Key Data 4 Niger 5 Africa 6 Chapter 2 8 Political Overview 8 History 9 Political Conditions 10 Political Risk Index 38 Political Stability 53 Freedom Rankings 68 Human Rights 80 Government Functions 82 Government Structure 84 Principal Government Officials 89 Leader Biography 90 Leader Biography 90 Foreign Relations 95 National Security 102 Defense Forces 104 Chapter 3 106 Economic Overview 106 Economic Overview 107 Nominal GDP and Components 109 Population and GDP Per Capita 111 Real GDP and Inflation 112 Government Spending and Taxation 113 Money Supply, Interest Rates and Unemployment 114 Foreign Trade and the Exchange Rate 115 Data in US Dollars 116 Energy Consumption and Production Standard Units 117 Energy Consumption and Production QUADS 119 World Energy Price Summary 120 CO2 Emissions 121 Agriculture Consumption and Production 122 World Agriculture Pricing Summary 124 Metals Consumption and Production 125 World Metals Pricing Summary 127 Economic Performance Index 128 Chapter 4 140 Investment Overview 140 Foreign Investment Climate 141 Foreign Investment Index 143 Corruption Perceptions Index 156 Competitiveness Ranking 168 Taxation 177 Stock Market 177 Partner Links 178 Chapter 5 179 Social Overview 179 People 180 Human Development Index 183 Life Satisfaction Index 187 Happy Planet Index 198 Status of Women 207 Global Gender Gap Index 209 Culture and Arts 219 Etiquette 219 Travel Information 220 Diseases/Health Data 230 Chapter 6 236 Environmental Overview 236 Environmental Issues 237 Environmental Policy 238 Greenhouse Gas Ranking 239 Global Environmental Snapshot 250 Global Environmental Concepts 261 International Environmental Agreements and Associations 275 Appendices 300 Bibliography 301 Niger Chapter 1 Country Overview Niger Review 2016 Page 1 of 313 pages Niger Country Overview NIGER Niger is a landlocked, western African country.