Beyond Ethnicity: African Protests in an Age of Inequality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arrêt N° 009/2016/CC/ME Du 07 Mars 2016

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER FRATERNITE-TRAVAIL-PROGRES COUR CONSTITUTIONNELLE Arrêt n° 009/CC/ME du 07 mars 2016 La Cour constitutionnelle statuant en matière électorale, en son audience publique du sept mars deux mil seize tenue au palais de ladite Cour, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LA COUR Vu la Constitution ; Vu la loi organique n° 2012-35 du 19 juin 2012 déterminant l’organisation, le fonctionnement de la Cour constitutionnelle et la procédure suivie devant elle ; Vu la loi n° 2014-01 du 28 mars 2014 portant régime général des élections présidentielles, locales et référendaires ; Vu le décret n° 2015-639/PRN/MISPD/ACR du 15 décembre 2015 portant convocation du corps électoral pour les élections présidentielles ; Vu l’arrêt n° 001/CC/ME du 9 janvier 2016 portant validation des candidatures aux élections présidentielles de 2016 ; Vu la lettre n° 250/P/CENI du 27 février 2016 du président de la Commission électorale nationale indépendante (CENI) transmettant les résultats globaux provisoires du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour, aux fins de validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 013/PCC du 27 février 2016 de Madame le Président portant désignation d’un Conseiller-rapporteur ; Vu les pièces du dossier ; Après audition du Conseiller-rapporteur et en avoir délibéré conformément à la loi ; EN LA FORME 1 Considérant que par lettre n° 250 /P/CENI en date du 27 février 2016, enregistrée au greffe de la Cour le même jour sous le n° 18 bis/greffe/ordre, le président de la Commission électorale nationale indépendante (CENI) a saisi la Cour aux fins de valider et proclamer les résultats définitifs du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour du 21 février 2016 ; Considérant qu’aux termes de l’article 120 alinéa 1 de la Constitution, «La Cour constitutionnelle est la juridiction compétente en matière constitutionnelle et électorale.» ; Que l’article 127 dispose que «La Cour constitutionnelle contrôle la régularité des élections présidentielles et législatives. -

Coup D'etat Events, 1946-2012

COUP D’ÉTAT EVENTS, 1946-2015 CODEBOOK Monty G. Marshall and Donna Ramsey Marshall Center for Systemic Peace May 11, 2016 Overview: This data list compiles basic descriptive information on all coups d’état occurring in countries reaching a population greater than 500,000 during the period 1946-2015. For purposes of this compilation, a coup d’état is defined as a forceful seizure of executive authority and office by a dissident/opposition faction within the country’s ruling or political elites that results in a substantial change in the executive leadership and the policies of the prior regime (although not necessarily in the nature of regime authority or mode of governance). Social revolutions, victories by oppositional forces in civil wars, and popular uprisings, while they may lead to substantial changes in central authority, are not considered coups d’état. Voluntary transfers of executive authority or transfers of office due to the death or incapacitance of a ruling executive are, likewise, not considered coups d’état. The forcible ouster of a regime accomplished by, or with the crucial support of, invading foreign forces is not here considered a coup d’état. The dataset includes four types of coup events: successful coups, attempted (failed) coups, coup plots, and alleged coup plots. In order for a coup to be considered “successful” effective authority must be exercised by new executive for at least one month. We are confident that the list of successful coups is comprehensive. Our confidence in the comprehensiveness of the coup lists diminishes across the remaining three categories: good coverage (reporting) of attempted coups and more questionable quality of coverage/reporting of coup plots (“discovered” and alleged). -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: ICR00001518 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT (TF-92835) ON A GRANT Public Disclosure Authorized UNDER THE GLOBAL FOOD CRISIS RESPONSE PROGRAM IN THE AMOUNT OF US$7.0 MILLION TO THE REPUBLIC OF NIGER FOR THE EMERGENCY FOOD SECURITY SUPPORT PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized June 28, 2010 Agricultural and Rural Development Unit (AFTAR) Sustainable Development Department Country Department AFCF2 Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective June 22, 2010) Currency Unit = Franc CFA US$1 = 535 CFAF FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AFTQK Operational Quality and Knowledge Services AHA Aménagements Hydroagricoles (Irrigated areas) ARD Agriculture and Rural Development ASPEN Africa Safeguards Policy Enhancement BCR Benefit/Cost Ratio BEEI Bureau des Evaluations d’Etudes d’Impact Environnemental (Office for the Evaluation of Environment Impact Studies) CA Centrale d’Approvisionnement (Central Agricultural Inputs Procurement Unit, within the Ministry of Agricultural Development) CAADP Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Program CAS Country Assistance Strategy CCA Cellule Crises Alimentaires (Food Crises Coordination Unit) CFA Communauté Financiaire Africaine CIC Communication and Information Center CIF Cost Insurance and Freight CMU Country Management Unit CRC Joint Government–Donor Food Crises Committee DAP Diammonium Phosphate DGA Direction Générale de l’Agriculture (General Directorat -

'Parti Nigérien Pour La Démocratie Et Le Socialisme' (PNDS)

Niger Klaas van Walraven President Mahamadou Issoufou and his ruling ‘Parti Nigérien pour la Démocratie et le Socialisme’ (PNDS) consolidated their grip on power, though not without push- ing to absurd levels the unorthodox measures by which they hoped to strengthen their position. Opposition leader Hama Amadou of the ‘Mouvement Démocratique Nigérien’ (Moden-Lumana), who had been arrested in 2015 for alleged involvement in a baby-trafficking scandal, remained in detention. He was allowed to contest the 2016 presidential elections from his cell. Issoufou emerged victorious, though not without an unexpected run-off. The parliamentary polls allowed the PNDS to boost its position in the National Assembly. Although the elections took place in an atmosphere of calm, they were marred by authoritarian interventions, including the arrest of several members of the opposition. The ‘Mouvement National pour la Société de Développement’ (MNSD) of Seini Oumarou had to cede its leader- ship of the opposition to Amadou’s Moden, which ended ahead of the MNSD in the Assembly. In August, the MNSD joined the presidential majority, which did not bode well for the possibility of political alternation in the future. National security was tested by frequent attacks by Boko Haram fighters in the south-east and raids by insurgents based in Mali. While the humanitarian situation in the south-east © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2�17 | doi 1�.1163/9789004355910_016 Niger 129 worsened, the army managed to strike back and engage in counter-insurgency oper- ations together with forces from Chad, Nigeria and Cameroon. Overall, the country held its own, despite being sandwiched between security challenges that caused some serious losses. -

Elections in Niger: Casting Ballots Or Casting Doubts?

Elections in Niger: casting ballots or casting doubts? Given its centrality to the Sahel region, the international community needs Niger to remain a bulwark of stability. While recent data collected throughout the country shows an increase in motivation to participate in this month's election, doubts about the electoral process and concerns for longstanding development issues mar the enthusiasm. Birnin Gaouré, Dosso, December 2020 By Johannes Claes and Rida Lyammouri with Navanti staff Published in collaboration with Niger could see its first democratic transition since independence as the country heads to the polls for the presidential election on 27 December.1 Current President Mahamadou Issoufou has indicated he will respect his constitutionally mandated two-term limit of 10 years, passing the flag to his protégé, Mohamed Bazoum. Political instability looms, however, as Issoufou and Bazoum’s Nigerien Party for Democracy and Socialism (PNDS) and a coalition of opposition parties fail to agree on the rules of the game. Political inclusion and enhanced trust in the institutions governing Niger’s electoral process are key if the risk of political crisis is to be avoided. Niger’s central role in Western policymakers’ security and political agendas in the Sahel — coupled with its history of four successful coups in 1976, 1994, 1999, and 2010 — serve to caution Western governments that preserving stability through political inclusion should take top priority over clinging to a political candidate that best represents foreign interests.2 During a turbulent electoral year in the region, Western governments must focus on the long-term goals of stabilizing and legitimizing Niger’s political system as a means of ensuring an ally in security and migration matters — not the other way around. -

MB 10Th April 2017

th 0795-3089 10 April, 2017 Vol. 12 No. 15 FG Reconstitutes Boards of Education Agencies, Councils of Universities Prof. Ayo Banjo, NUC Hon. Emeka Nwajiuba, TETFund Prof. Zainab Alkali, NLN resident Muhammadu statement said, Mr. President, in ?N a t i o n a l U n i v e r s i t i e s B u h a r i , G C F R , h a s making these appointments, had Commission (NUC): Prof. Ayo Papproved the reconstitution taken congnisance of the provisions Banjo of the Boards of 19 Agencies and of the respective legislation with ?Tertiary Education Trust Fund Parastatals, under the Federal respect to composition, competence, ( T E T F u n d ) : C h i e f E m e k a Ministry of Education, for a period credibility, integrity, federal Nwajiuba of four years, in the first instance. character and geo-political spread. ?N a t i o n a l I n s t i t u t e f o r The Honourable Minister of Educational Planning and Education, Malam Adamu Adamu, The Agencies and their Chairmen Administration (NIEPA): Hon. Dr. who made this known in a are as follows: Ekaete Ebong Okon in this edition President Buhari Tasks FUTA Obey NUC Regulations on Excellence Pg. 4 -Prof Rasheed at EKSU Convocation Pg. 7 10th April, 2017 Vol. 12 No. 15 Senator Nkechi Justina Nwaogu, UNICAL Dr. Aboki Zhawa, FUNAAB Prince Tony Momoh, UNIJOS ?Universal Basic Education Matriculation Board (JAMB): Dr. The Honourable Minister’s Commission (UBEC): Dr. Mahmud Emmanuel Ndukwe statement read in part: “In making Mohammed ?National Institute of Nigerian these appointments, Mr. -

He Embarked on a Strong Move to Develop Uganda Very Quickly After Independence. His Achievements Were So Good That the President

SPEECH BY MAMA MIRIA OBOTE IN HONOUR OF THE FOUNDING FATHERS OF THE EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY, AT ARUSHA TANZANIA 31ST MAY2015. Introduction We are delighted, humbled and honoured, to stand before this august EAL Assembly representing our Founding Fathers of the East African Community, comrades Dr.Julius Kambarage Nyerere, Mzee J omo Kenyatta and Apollo Milton Obote. As far as the Obotes are concerned we are true East Africans because of the long experience of living, studying and working in East Africa. Dr. Obote lived and worked in Kenya in the 19 50s when the Mau Mau struggle was taking place and had the golden opportunity of meeting the legendary freedom fighter, Dedan Kimathi, When political activities were banned in Kenya, the focus shifted to social clubs and Dr. Obote went on to head the Kaloleni Social Club. Later the ban on political activities was lifted and Dr. Obote together with other Kenyan nationalists went ahead to found K.A.U, the Kenyan African Union. Dr. Obote was even elected Chairperson of the new party and he led the successful campaigns for the late Tom Mboya's entry into to the L.E.G.C.0. I, myself am equally a product of the East African spirit and Kenya. My late father Blasio Kalule was an employee of the Kenya-Uganda Railway and we lived in Nairobi, Kenya, for a while. With the advent of exile in 1971 to 1980 we lived in Tanzania and during our second exile, 1985 - 2005, we lived in both Kenya and Zambia. Our children have studied in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda, thus our association with both the old and new East African Community. -

Outlines of Global Transformations

SPECIAL ISSUE • 2019 ISSN 2542-0240 (Print) ISSN 2587-9324 (Online) ogt-journal.com OUTLINES OF GLOBAL TRANSFORMATIONS Modern Africa in Global Economy and Politics SPECIAL ISSUE • 2019 Outlines of Global Transformations: POLITICS • ECONOMICS • LAW SPECIAL ISSUE • 2019 ISSN 2542-0240 (PRINT), ISSN 2587-9324 (ONLINE) Outlines of Global Transformations POLITICS • ECONOMICS • LAW Kontury global,nyh transformacij: politika, èkonomika, pravo The Outlines of Global Transformations Journal publishes papers on the urgent aspects of contemporary politics, world affairs, economics and law. The journal is aimed to unify the representatives of Russian and foreign academic and expert communities, the adherents of different scientific schools. It provides a reader with the profound analysis of a problem and shows different approaches for its solution. Each issue is dedicated to a concrete problem considered in a complex way. Editorial Board Alexey V. Kuznetsov – Editor-in-Chief, INION, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russian Federation Vladimir B. Isakov – Deputy Editor-in-Chief, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russian Federation Vladimir N. Leksin – Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Institute of System Analysis, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russian Federation Alexander I. Solovyev – Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russian Federation Vardan E. Bagdasaryan, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russian Federation Aleksey A. Krivopalov, Center for Crisis Society Studies, Moscow, Russian Federation Andrew C. Kuchins, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, USA Alexander M. Libman, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany Alexander Ya. Livshin, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russian Federation Kari Liuhto, University of Turku, Turku, Finland Alexander V. Lukin, MGIMO University, Moscow, Russian Federation Andrei Y. -

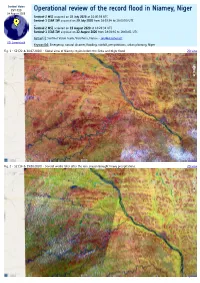

Operational Review of the Record Flood in Niamey, Niger

Sentinel Vision EVT-719 Operational review of the record flood in Niamey, Niger 24 August 2020 Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 22 July 2020 at 10:05:59 UTC Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 29 July 2020 from 18:03:34 to 18:03:59 UTC ... Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 19 August 2020 at 10:20:31 UTC Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 22 August 2020 from 18:03:36 to 18:04:01 UTC Author(s): Sentinel Vision team, VisioTerra, France - [email protected] 2D Layerstack Keyword(s): Emergency, natural disaster, flooding, rainfall, precipitations, urban planning, Niger Fig. 1 - S2 (22 & 30.07.2020) - Global view of Niamey region before the Sirba and Niger flood. 2D view Fig. 2 - S2 (16 & 19.08.2020) - Several weeks later after the rain season brought heavy precipitations. 2D view / Based in Niger, the local early warning system for Sirba floods (Système Local d’Alerte Précoce pour les Inondations de la Sirba, SLAPIS) reported: In Niamey, following the rainfall received in the south-western part of Niger and Burkina Faso, the water level observed at the hydrometric station of Niamey rose to 650 cm on 18/08/2020 at 09:00. This is a water level never reached in the past. Sandbags were placed on the dyke downstream of the Kennedy Bridge to prevent the water from overflowing it. Left: Hydrological stations network of the Niger river basin - Source: Niger Basin Authority Right: Cumulative precipitation in the Niger river basin over the past 3 dekads [mm] - Source: Niger Basin Authority Fig. -

Niger 1 Niger

Niger 1 Niger République du Niger (fr) (Détails) (Détails) Devise nationale : Fraternité, travail, progrès Langue officielle Français (langue officielle) une vingtaine de « langues nationales » Capitale Niamey 13°32′N, 2°05′E Plus grande ville Niamey Forme de l’État République - Président Mamadou Tandja - Premier Ali Badjo Gamatié ministre Superficie Classé 22e - Totale 1 267 000 km² - Eau (%) Négligeable Population Classé 73e - Totale (2008) 13 272 679 hab. - Densité 10 hab./km² Indépendance de la France - date 3 août 1960 Gentilé Nigériens [1] IDH (2005) 0,374 (faible) ( 174e ) Monnaie Franc CFA (XOF) Fuseau horaire UTC +1 Hymne national 'La Nigérienne' Domaine internet .ne Indicatif +227 téléphonique Niger 2 Le Niger, officiellement la République du Niger, est un pays d'Afrique de l'Ouest steppique, situé entre l'Algérie, le Bénin, le Burkina Faso, le Tchad, la Libye, le Mali et le Nigeria. La capitale est Niamey. Les habitants sont des Nigériens (ceux du Nigeria sont des Nigérians). Le pays est multiethnique et constitue une terre de contact entre l'Afrique noire et l'Afrique du Nord. Les plus importantes ressources naturelles du Niger sont l'or, le fer, le charbon, l'uranium et le pétrole. Certains animaux, comme les éléphants, les lions et les girafes, sont en danger de disparition en raison de la destruction de la forêt et du braconnage. Le dernier troupeau de girafes en liberté de toute l'Afrique de l'Ouest évolue dans les environs du village de Kouré, à 60 km de la capitale Niamey. D'autre part, Carte du Niger une réserve portant le nom de "Parc du W" (à cause des sinuosités du fleuve Niger à cet endroit) se trouve sur le territoire de trois pays : le Niger, le Bénin et le Burkina Faso. -

The Emergence of Hausa As a National Lingua Franca in Niger

Ahmed Draia University – Adrar Université Ahmed Draia Adrar-Algérie Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Letters and Language A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Master’s Degree in Linguistics and Didactics The Emergence of Hausa as a National Lingua Franca in Niger Presented by: Supervised by: Moussa Yacouba Abdoul Aziz Pr. Bachir Bouhania Academic Year: 2015-2016 Abstract The present research investigates the causes behind the emergence of Hausa as a national lingua franca in Niger. Precisely, the research seeks to answer the question as to why Hausa has become a lingua franca in Niger. To answer this question, a sociolinguistic approach of language spread or expansion has been adopted to see whether it applies to the Hausa language. It has been found that the emergence of Hausa as a lingua franca is mainly attributed to geo-historical reasons such as the rise of Hausa states in the fifteenth century, the continuous processes of migration in the seventeenth century which resulted in cultural and linguistic assimilation, territorial expansion brought about by the spread of Islam in the nineteenth century, and the establishment of long-distance trade by the Hausa diaspora. Moreover, the status of Hausa as a lingua franca has recently been maintained by socio- cultural factors represented by the growing use of the language for commercial and cultural purposes as well as its significance in education and media. These findings arguably support the sociolinguistic view regarding the impact of society on language expansion, that the widespread use of language is highly determined by social factors. -

National Symbols As Commemorative Emblems in Nigerian Films

European Scientific Journal January 2018 edition Vol.14, No.2 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 National Symbols as Commemorative Emblems in Nigerian Films Alawode, Sunday Olayinka PhD Adesanya, Oluseyi Olufunke Agboola, Olufunsho Cole Lagos State University School Of Communication Lagos, Osodi, Lagos State, Nigeria Religion, Communication and Culture Working Group Doi: 10.19044/esj.2018.v14n2p100 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2018.v14n2p100 Abstract Nigerian films worldwide are the entertainment offerings of the nation, a burgeoning industry with steady increase growth rate and contributing substantially to the GDP of the nation. National symbols are objects, entities and relics representing an idea, concept, character that may be physical, abstract, religious, cultural, and linguistic among others in a sovereign context and beyond. Symbols or objects that connected together may not have anything in common in reality but by association and common agreement, they have come to represent each other in social contexts; a symbol may arbitrarily denote a referent, icon and index. In the case of Nigeria, the National flag, Anthem, Pledge, Currency, language, Coat of arms, National institutions like the National Assembly complex, Federal Capital Territory (FCT), images of past leaders, historical monuments like the Unknown Soldier (representing military men who died in the cause of protecting the nation), dresses are some of these national symbols. Apart from commemorative historical functions, national symbols are also used to represent hard work, credibility or truthfulness, as well as ethnic differentiation, religious affiliation, cultural background, social status, professional orientation, class distinction among others. Theorizing with Gate-keeping and Framing Analysis, this study adopts a content analysis design which is the study of recorded human communications, an objective and systematic analysis of the contents of any document that are manifest.