Elections in Niger: Casting Ballots Or Casting Doubts?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arrêt N° 009/2016/CC/ME Du 07 Mars 2016

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER FRATERNITE-TRAVAIL-PROGRES COUR CONSTITUTIONNELLE Arrêt n° 009/CC/ME du 07 mars 2016 La Cour constitutionnelle statuant en matière électorale, en son audience publique du sept mars deux mil seize tenue au palais de ladite Cour, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LA COUR Vu la Constitution ; Vu la loi organique n° 2012-35 du 19 juin 2012 déterminant l’organisation, le fonctionnement de la Cour constitutionnelle et la procédure suivie devant elle ; Vu la loi n° 2014-01 du 28 mars 2014 portant régime général des élections présidentielles, locales et référendaires ; Vu le décret n° 2015-639/PRN/MISPD/ACR du 15 décembre 2015 portant convocation du corps électoral pour les élections présidentielles ; Vu l’arrêt n° 001/CC/ME du 9 janvier 2016 portant validation des candidatures aux élections présidentielles de 2016 ; Vu la lettre n° 250/P/CENI du 27 février 2016 du président de la Commission électorale nationale indépendante (CENI) transmettant les résultats globaux provisoires du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour, aux fins de validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 013/PCC du 27 février 2016 de Madame le Président portant désignation d’un Conseiller-rapporteur ; Vu les pièces du dossier ; Après audition du Conseiller-rapporteur et en avoir délibéré conformément à la loi ; EN LA FORME 1 Considérant que par lettre n° 250 /P/CENI en date du 27 février 2016, enregistrée au greffe de la Cour le même jour sous le n° 18 bis/greffe/ordre, le président de la Commission électorale nationale indépendante (CENI) a saisi la Cour aux fins de valider et proclamer les résultats définitifs du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour du 21 février 2016 ; Considérant qu’aux termes de l’article 120 alinéa 1 de la Constitution, «La Cour constitutionnelle est la juridiction compétente en matière constitutionnelle et électorale.» ; Que l’article 127 dispose que «La Cour constitutionnelle contrôle la régularité des élections présidentielles et législatives. -

Republique Du Niger Cour Constitutionnelle

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER FRATERNITE-TRAVAIL-PROGRES COUR CONSTITUTIONNELLE Arrêt n° 005/CC/ME du 13 novembre 2020 La Cour constitutionnelle statuant en matière électorale, en son audience publique du treize novembre deux mil vingt tenue au palais de ladite Cour, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LA COUR Vu la Constitution ; Vu la loi organique n° 2012-35 du 19 juin 2012 déterminant l’organisation, le fonctionnement de la Cour constitutionnelle et la procédure suivie devant elle, modifiée et complétée par la loi n° 2020-36 du 30 juillet 2020 ; Vu la loi n° 2017-64 du 14 août 2017 portant Code électoral du Niger, modifiée et complétée par la loi n° 2019-38 du 18 juillet 2019 ; Vu le décret n° 2020-733/PRN/MI/SP/D/ACR du 25 septembre 2020 portant convocation du corps électoral pour les élections présidentielles 1er tour 2020 ; Vu la requête en date du 11 novembre 2020 de Monsieur le Ministre de l’Intérieur, chargé des questions électorales ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 33/PCC du 12 novembre 2020 de Monsieur le Président portant désignation d’un Conseiller-rapporteur ; Vu les pièces du dossier ; Après audition du Conseiller-rapporteur et en avoir délibéré conformément à la loi ; EN LA FORME Considérant que par lettre n° 05556/MISPD/ACR/DGAPJ/DLP en date du 11 novembre 2020, enregistrée au greffe de la Cour le même jour sous le n° 30/greffe/ordre, Monsieur le Ministre de l’Intérieur, chargé des questions électorales transmettait à la Cour constitutionnelle, conformément aux dispositions de l’article 128 de la loi organique n° 2017-64 du 14 août 2017 portant Code Electoral du Niger, modifiée et complétée par la loi n° 2019-38 du 18 juillet 2019, pour examen et validation, quarante-un (41) dossiers de candidature produits par les personnalités ci-après, candidates aux élections présidentielles 2020-2021 : 1. -

'Parti Nigérien Pour La Démocratie Et Le Socialisme' (PNDS)

Niger Klaas van Walraven President Mahamadou Issoufou and his ruling ‘Parti Nigérien pour la Démocratie et le Socialisme’ (PNDS) consolidated their grip on power, though not without push- ing to absurd levels the unorthodox measures by which they hoped to strengthen their position. Opposition leader Hama Amadou of the ‘Mouvement Démocratique Nigérien’ (Moden-Lumana), who had been arrested in 2015 for alleged involvement in a baby-trafficking scandal, remained in detention. He was allowed to contest the 2016 presidential elections from his cell. Issoufou emerged victorious, though not without an unexpected run-off. The parliamentary polls allowed the PNDS to boost its position in the National Assembly. Although the elections took place in an atmosphere of calm, they were marred by authoritarian interventions, including the arrest of several members of the opposition. The ‘Mouvement National pour la Société de Développement’ (MNSD) of Seini Oumarou had to cede its leader- ship of the opposition to Amadou’s Moden, which ended ahead of the MNSD in the Assembly. In August, the MNSD joined the presidential majority, which did not bode well for the possibility of political alternation in the future. National security was tested by frequent attacks by Boko Haram fighters in the south-east and raids by insurgents based in Mali. While the humanitarian situation in the south-east © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2�17 | doi 1�.1163/9789004355910_016 Niger 129 worsened, the army managed to strike back and engage in counter-insurgency oper- ations together with forces from Chad, Nigeria and Cameroon. Overall, the country held its own, despite being sandwiched between security challenges that caused some serious losses. -

Fin De Parcours Pour Le Candidat Du Pnds

«Le plus difficile au monde est de dire en y pensant ce que tout le monde dit sans y penser» LE COURRIERHORS SERIE Hebdomadaire d’Informations générales et de réflexion - N° HORS SERIE du JEUDI 13 NOVEMBRE 2020 - Prix : 300 Francs CFA LES VRAIES FAUSSES PIÈCES D'ÉTAT-CIVIL DE BAZOUM Fin de parcours pour le candidat du Pnds Bazoum est probablement pris dans la nasse. Ses pièces d'état- temps (paix à son âme). Son épouse s'appelle Hadiza Abdallah, et civil, abondamment partagées sur les réseaux et objet d'une assi- non Fatouma comme il est paru dans les colonnes du courrier du gnation en contentieux de nationalité à Diffa, sont manifestement jeudi 11 novembre 2020. C'est cette dame, nigérienne d'origine, mais de vraies fausses. Outre le fait, insolite que Bazoum a obtenu son belle-sœur de Bazoum, dont les pièces d'état-civil, notamment l'ac- certificat de nationalité le 11 juillet 1985, dès le lendemain de l'ob- te de naissance, va servir à établir la fausse nationalité de Bazoum. tention d'un jugement supplétif tenant lieu d'acte de naissance, Le candidat du Pnds s'appelle, en réalité, non pas Bazoum Moha- les documents d'état-civil du candidat du Pnds présentent plein med, mais plutôt Bazoum Salim, comme tous es frères et sœurs. Et d'anachronismes d'aberrations utiles à découvrir. c'est sûrement pour immortaliser le nom de ce père dont il ne pas, D'abord, son jugement supplétif de naissance, obtenu le 10 juillet par opportunisme, le nom, que Bazoum a donné le nom de Salim à 1985 le déclare fils de Mohamed alors que ce dernier est en réalité un de ses enfants. -

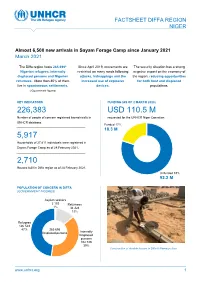

UNHCR Niger Operation UNHCR Database

FACTSHEET DIFFA REGION NIGER Almost 6,500 new arrivals in Sayam Forage Camp since January 2021 March 2021 NNNovember The Diffa region hosts 265,696* Since April 2019, movements are The security situation has a strong Nigerian refugees, internally restricted on many roads following negative impact on the economy of displaced persons and Nigerien attacks, kidnappings and the the region, reducing opportunities returnees. More than 80% of them increased use of explosive for both host and displaced live in spontaneous settlements. devices. populations. (*Government figures) KEY INDICATORS FUNDING (AS OF 2 MARCH 2020) 226,383 USD 110.5 M Number of people of concern registered biometrically in requested for the UNHCR Niger Operation UNHCR database. Funded 17% 18.3 M 5,917 Households of 27,811 individuals were registered in Sayam Forage Camp as of 28 February 2021. 2,710 Houses built in Diffa region as of 28 February 2021. Unfunded 83% 92.2 M the UNHCR Niger Operation POPULATION OF CONCERN IN DIFFA (GOVERNMENT FIGURES) Asylum seekers 2 103 Returnees 1% 34 324 13% Refugees 126 543 47% 265 696 Displaced persons Internally Displaced persons 102 726 39% Construction of durable houses in Diffa © Ramatou Issa www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > Niger - Diffa / March 2021 Operation Strategy The key pillars of the UNHCR strategy for the Diffa region are: ■ Ensure institutional resilience through capacity development and support to the authorities (locally elected and administrative authorities) in the framework of the Niger decentralisation process. ■ Strengthen the out of camp policy around the urbanisation program through sustainable interventions and dynamic partnerships including with the World Bank. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the Use of Cerf Funds Niger Rapid Response Conflict-Related Displacement

RESIDENT / HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS NIGER RAPID RESPONSE CONFLICT-RELATED DISPLACEMENT RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR Mr. Fodé Ndiaye REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. Since the implementation of the response started, OCHA has regularly asked partners to update a matrix related to the state of implementation of activities, as well as geographical location of activities. On February 26, CERF-focal points from all agencies concerned met to kick off the reporting process and establish a framework. This was followed up by submission of individual projects and input in the following weeks, as well as consolidation and consultation in terms of the draft for the report. b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team and by cluster/sector coordinators as outlined in the guidelines. YES NO c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders as recommended in the guidelines (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant government counterparts)? YES NO The CERF Report has been shared with Cluster Coordinator and recipient agencies. 2 I. HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT TABLE 1: EMERGENCY ALLOCATION OVERVIEW (US$) Total amount required for the humanitarian response: 53,047,888 Source Amount CERF 5,181,281 Breakdown -

Niger 1 Niger

Niger 1 Niger République du Niger (fr) (Détails) (Détails) Devise nationale : Fraternité, travail, progrès Langue officielle Français (langue officielle) une vingtaine de « langues nationales » Capitale Niamey 13°32′N, 2°05′E Plus grande ville Niamey Forme de l’État République - Président Mamadou Tandja - Premier Ali Badjo Gamatié ministre Superficie Classé 22e - Totale 1 267 000 km² - Eau (%) Négligeable Population Classé 73e - Totale (2008) 13 272 679 hab. - Densité 10 hab./km² Indépendance de la France - date 3 août 1960 Gentilé Nigériens [1] IDH (2005) 0,374 (faible) ( 174e ) Monnaie Franc CFA (XOF) Fuseau horaire UTC +1 Hymne national 'La Nigérienne' Domaine internet .ne Indicatif +227 téléphonique Niger 2 Le Niger, officiellement la République du Niger, est un pays d'Afrique de l'Ouest steppique, situé entre l'Algérie, le Bénin, le Burkina Faso, le Tchad, la Libye, le Mali et le Nigeria. La capitale est Niamey. Les habitants sont des Nigériens (ceux du Nigeria sont des Nigérians). Le pays est multiethnique et constitue une terre de contact entre l'Afrique noire et l'Afrique du Nord. Les plus importantes ressources naturelles du Niger sont l'or, le fer, le charbon, l'uranium et le pétrole. Certains animaux, comme les éléphants, les lions et les girafes, sont en danger de disparition en raison de la destruction de la forêt et du braconnage. Le dernier troupeau de girafes en liberté de toute l'Afrique de l'Ouest évolue dans les environs du village de Kouré, à 60 km de la capitale Niamey. D'autre part, Carte du Niger une réserve portant le nom de "Parc du W" (à cause des sinuosités du fleuve Niger à cet endroit) se trouve sur le territoire de trois pays : le Niger, le Bénin et le Burkina Faso. -

LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building NIGER

Co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union LAW ENFORCEMENT TRAINING FOR CAPACITY BUILDING LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building NIGER Downloadable Country Booklet DL. 2.5 (Ve 1.2) Dissemination level: PU Let4Cap Grant Contract no.: HOME/ 2015/ISFP/AG/LETX/8753 Start date: 01/11/2016 Duration: 33 months Dissemination Level PU: Public X PP: Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission) RE: Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission) Revision history Rev. Date Author Notes 1.0 20/03/2018 SSSA Overall structure and first draft 1.1 06/05/2018 SSSA Second version after internal feedback among SSSA staff 1.2 09/05/2018 SSSA Final version version before feedback from partners LET4CAP_WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable_2.5 VER1.2 WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable Deliverable 2.5 Downloadable country booklets VER V. 1 . 2 2 NIGER Country Information Package 3 This Country Information Package has been prepared by Eric REPETTO and Claudia KNERING, under the scientific supervision of Professor Andrea de GUTTRY and Dr. Annalisa CRETA. Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy www.santannapisa.it LET4CAP, co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union, aims to contribute to more consistent and efficient assistance in law enforcement capacity building to third countries. The Project consists in the design and provision of training interventions drawn on the experience of the partners and fine-tuned after a piloting and consolidation phase. © 2018 by LET4CAP All rights reserved. 4 Table of contents 1. Country Profile 1.1Country in Brief 1.2Modern and Contemporary History of Niger 1.3 Geography 1.4Territorial and Administrative Units 1.5 Population 1.6Ethnic Groups, Languages, Religion 1.7Health 1.8Education and Literacy 1.9Country Economy 2. -

RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: March 2018

Niger RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: March 2018 KNOWYOURCOUNTRY.COM Executive Summary - Niger Sanctions: None FAFT list of AML No Deficient Countries Non - Compliance with FATF 40 + 9 Recommendations Higher Risk Areas: Weakness in Government Legislation to combat Money Laundering Not on EU White list equivalent jurisdictions Corruption Index (Transparency International & W.G.I.) World Governance Indicators (Average Score) Failed States Index (Political Issues)(Average Score) Major Investment Areas: Agriculture - products: cowpeas, cotton, peanuts, millet, sorghum, cassava (manioc), rice; cattle, sheep, goats, camels, donkeys, horses, poultry Industries: uranium mining, cement, brick, soap, textiles, food processing, chemicals, slaughterhouses Exports - commodities: uranium ore, livestock, cowpeas, onions Exports - partners: Nigeria 41%, US 17%, India 14.1%, Italy 8.5%, China 7.7%, Ghana 5.7% (2012) Imports - commodities: foodstuffs, machinery, vehicles and parts, petroleum, cereals Imports - partners: France 14.2%, China 11.1%, French Polynesia 9.9%, Nigeria 9.7%, Togo 5.5% (2012) Investment Restrictions: Niger is eager to attract foreign investment and has taken steps to improve the business climate. The Government of Niger (GON) has made revisions to the investment code in 1 order to make petroleum and mining exploration and production more attractive to foreign investors. The Investment Code offers advantages to sectors the GON deems key to economic development: energy production, mineral exploration and mining, agriculture, food processing, forestry, fishing, low-cost housing construction, handicrafts, hotels, schools, health centres, and transportation. Total foreign ownership is permitted in most sectors except energy, mineral resources, and sectors restricted for national security purposes. Foreign ownership of land is permitted but requires authorization from the Ministry of Planning, Land Management and Community Development. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE POLITICS OF ELECTORAL REFORM IN FRANCOPHONE WEST AFRICA: THE BIRTH AND CHANGE OF ELECTORAL RULES IN MALI, NIGER, AND SENEGAL By MAMADOU BODIAN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Mamadou Bodian To my late father, Lansana Bodian, for always believing in me ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want first to thank and express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Leonardo A. Villalón, who has been a great mentor and good friend. He has believed in me and prepared me to get to this place in my academic life. The pursuit of a degree in political science would not be possible without his support. I am also grateful to my committee members: Bryon Moraski, Michael Bernhard, Daniel A. Smith, Lawrence Dodd, and Fiona McLaughlin for generously offering their time, guidance and good will throughout the preparation and review of this work. This dissertation grew in the vibrant intellectual atmosphere provided by the University of Florida. The Department of Political Science and the Center for African Studies have been a friendly workplace. It would be impossible to list the debts to professors, students, friends, and colleagues who have incurred during the long development and the writing of this work. Among those to whom I am most grateful are Aida A. Hozic, Ido Oren, Badredine Arfi, Kevin Funk, Sebastian Sclofsky, Oumar Ba, Lina Benabdallah, Amanda Edgell, and Eric Lake. I am also thankful to fellow Africanists: Emily Hauser, Anna Mwaba, Chesney McOmber, Nic Knowlton, Ashley Leinweber, Steve Lichty, and Ann Wainscott. -

Report of the Human Rights Promotion Mission to the Republic of Niger by Commissioner Soyata Maiga

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Commission Africaine des Droits de African Commission on Human & l’Homme & des Peuples Peoples’ Rights No. 31 Bijilo Annex Lay-out, Kombo North District, Western Region, P. O. Box 673, Banjul, The Gambia Tel: (220) (220) 441 05 05 /441 05 06, Fax: (220) 441 05 04 E-mail: [email protected], www.achpr.org REPORT OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS PROMOTION MISSION TO THE REPUBLIC OF NIGER BY COMMISSIONER SOYATA MAIGA 18 – 27 July, 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the African Commission) expresses its gratitude to the Government and the highest authorities of the Republic of Niger for accepting to host the promotion mission to the country from 18 to 27 July, 2011 and for providing the delegation with all the necessary facilities and the required personnel for the smooth conduct of the mission. The African Commission expresses its special thanks to H.E. Mr. Marou Amadou, Minister of Justice, Keeper of the Seals and Government Spokesperson, whose personal involvement in the organization of the various meetings contributed greatly to the success of the mission. Finally, it would like to thank Madam Maïga Zeinabou Labo, Director of Human Rights and Social Policy at the Ministry of Justice as well as the staff at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Cooperation and Integration who accompanied the delegation throughout the mission and facilitated the various meetings. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TERMS OF REFERENCE OF THE MISSION COMPOSITION OF THE DELEGATION PRESENTATION AND GENERAL BACKGROUND OF NIGER METHDOLOGY AND CONDUCT OF THE MISSION MEETING WITH H.E.