The Role of Zoos in Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Molecular Phylogeny of the Pheasants and Partridges Suggests That These Lineages Are Not Monophyletic R

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution Vol. 11, No. 1, February, pp. 38–54, 1999 Article ID mpev.1998.0562, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on A Molecular Phylogeny of the Pheasants and Partridges Suggests That These Lineages Are Not Monophyletic R. T. Kimball,* E. L. Braun,*,† P. W. Zwartjes,* T. M. Crowe,‡,§ and J. D. Ligon* *Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131; †National Center for Genome Resources, 1800 Old Pecos Trail, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87505; ‡Percy FitzPatrick Institute, University of Capetown, Rondebosch, 7700, South Africa; and §Department of Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, New York 10024-5192 Received October 8, 1997; revised June 2, 1998 World partridges are smaller and widely distributed in Cytochrome b and D-loop nucleotide sequences were Asia, Africa, and Europe. Most partridge species are used to study patterns of molecular evolution and monochromatic and primarily dull colored. None exhib- phylogenetic relationships between the pheasants and its the extreme or highly specialized ornamentation the partridges, which are thought to form two closely characteristic of the pheasants. related monophyletic galliform lineages. Our analyses Although the order Galliformes is well defined, taxo- used 34 complete cytochrome b and 22 partial D-loop nomic relationships are less clear within the group sequences from the hypervariable domain I of the (Verheyen, 1956), due to the low variability in anatomi- D-loop, representing 20 pheasant species (15 genera) and 12 partridge species (5 genera). We performed cal and osteological traits (Blanchard, 1857, cited in parsimony, maximum likelihood, and distance analy- Verheyen, 1956; Lowe, 1938; Delacour, 1977). -

A Complete Species-Level Molecular Phylogeny For

Author's personal copy Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 47 (2008) 251–260 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A complete species-level molecular phylogeny for the ‘‘Eurasian” starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnus, Acridotheres, and allies): Recent diversification in a highly social and dispersive avian group Irby J. Lovette a,*, Brynn V. McCleery a, Amanda L. Talaba a, Dustin R. Rubenstein a,b,c a Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, Laboratory of Ornithology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14950, USA b Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA c Department of Integrative Biology and Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Received 2 August 2007; revised 17 January 2008; accepted 22 January 2008 Available online 31 January 2008 Abstract We generated the first complete phylogeny of extant taxa in a well-defined clade of 26 starling species that is collectively distributed across Eurasia, and which has one species endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. Two species in this group—the European starling Sturnus vulgaris and the common Myna Acridotheres tristis—now occur on continents and islands around the world following human-mediated introductions, and the entire clade is generally notable for being highly social and dispersive, as most of its species breed colonially or move in large flocks as they track ephemeral insect or plant resources, and for associating with humans in urban or agricultural land- scapes. Our reconstructions were based on substantial mtDNA (4 kb) and nuclear intron (4 loci, 3 kb total) sequences from 16 species, augmented by mtDNA NDII gene sequences (1 kb) for the remaining 10 taxa for which DNAs were available only from museum skin samples. -

Traffic.Org/Home/2015/12/4/ Thousands-Of-Birds-Seized-From-East-Java-Port.Html

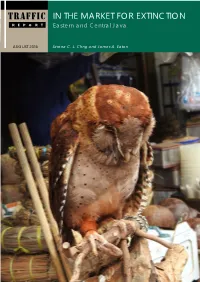

TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION REPORT Eastern and Central Java AUGUST 2016 Serene C. L. Chng and James A. Eaton TRAFFIC Report: In The Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java 1 TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC. Southeast Asia Regional Office Unit 3-2, 1st Floor, Jalan SS23/11 Taman SEA, 47400 Petaling Jaya Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. © TRAFFIC 2016. ISBN no: 978-983-3393-50-3 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722. Suggested citation: Chng, S.C.L. and Eaton, J.A. (2016). In the Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java. TRAFFIC. Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Front cover photograph: An Oriental Bay Owl Phodilus badius displayed for sale at Malang Bird Market Credit: Heru Cahyono/TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION Eastern and Central Java Serene C. -

Wild Turkey Education Guide

Table of Contents Section 1: Eastern Wild Turkey Ecology 1. Eastern Wild Turkey Quick Facts………………………………………………...pg 2 2. Eastern Wild Turkey Fact Sheet………………………………………………….pg 4 3. Wild Turkey Lifecycle……………………………………………………………..pg 8 4. Eastern Wild Turkey Adaptations ………………………………………………pg 9 Section 2: Eastern Wild Turkey Management 1. Wild Turkey Management Timeline…………………….……………………….pg 18 2. History of Wild Turkey Management …………………...…..…………………..pg 19 3. Modern Wild Turkey Management in Maryland………...……………………..pg 22 4. Managing Wild Turkeys Today ……………………………………………….....pg 25 Section 3: Activity Lesson Plans 1. Activity: Growing Up WILD: Tasty Turkeys (Grades K-2)……………..….…..pg 33 2. Activity: Calling All Turkeys (Grades K-5)………………………………..…….pg 37 3. Activity: Fit for a Turkey (Grades 3-5)…………………………………………...pg 40 4. Activity: Project WILD adaptation: Too Many Turkeys (Grades K-5)…..…….pg 43 5. Activity: Project WILD: Quick, Frozen Critters (Grades 5-8).……………….…pg 47 6. Activity: Project WILD: Turkey Trouble (Grades 9-12………………….……....pg 51 7. Activity: Project WILD: Let’s Talk Turkey (Grades 9-12)..……………..………pg 58 Section 4: Additional Activities: 1. Wild Turkey Ecology Word Find………………………………………….…….pg 66 2. Wild Turkey Management Word Find………………………………………….pg 68 3. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 70 4. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 71 5. Turkey Color-by-Letter……………………………………..…………………….pg 72 6. Five Little Turkeys Song Sheet……. ………………………………………….…pg 73 7. Thankful Turkey…………………..…………………………………………….....pg 74 8. Graph-a-Turkey………………………………….…………………………….…..pg 75 9. Turkey Trouble Maze…………………………………………………………..….pg 76 10. What Animals Made These Tracks………………………………………….……pg 78 11. Drinking Straw Turkey Call Craft……………………………………….….……pg 80 Section 5: Wild Turkey PowerPoint Slide Notes The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin or physical or mental disability. -

Records of Four Critically Endangered Songbirds in the Markets of Java Suggest Domestic Trade Is a Major Impediment to Their Conservation

20 BirdingASIA 27 (2017): 20–25 CONSERVATION ALERT Records of four Critically Endangered songbirds in the markets of Java suggest domestic trade is a major impediment to their conservation VINCENT NIJMAN, SUCI LISTINA SARI, PENTHAI SIRIWAT, MARIE SIGAUD & K. ANNEISOLA NEKARIS Introduction 1.2 million wild-caught birds (the vast majority Bird-keeping is a popular pastime in Indonesia, and of them songbirds) were sold in the Java and Bali nowhere more so than amongst the people of Java. markets each year. Taking a different approach, It has deep cultural roots, and traditionally a kukilo Jepson & Ladle (2005) made use of a survey of (bird in the Javanese language) was one of the five randomly selected households in the Javan cities things a Javanese man should pursue or obtain in of Jakarta, Bandung, Semarang and Surabaya, order to live a fulfilling life (the others being garwo, and Medan in Sumatra, which together make up a wife, curigo, a Javanese dagger, wismo, a house or a quarter of the urban Indonesian population, to a place to live, and turonggo, a horse, as a means estimate that between 600,000 and 760,000 wild- of transportation). A kukilo represents having a caught native songbirds were acquired each year. hobby, and it often takes the form of owning a Extrapolating this to the urban population of Java, perkutut (Zebra Dove Geopelia striata) or a kutilang which amounts to 60% of Indonesia’s total, it (Sooty-headed Bulbul Pycnonotus aurigaster) but suggests that a total of 1.4–1.8 million wild-caught also a wide range of other birds (Nash 1993, Chng native songbirds were acquired. -

Illegal Trade Pushing the Critically Endangered Black-Winged Myna Acridotheres Melanopterus Towards Imminent Extinction

Bird Conservation International, page 1 of 7 . © BirdLife International, 2015 doi:10.1017/S0959270915000106 Short Communication Illegal trade pushing the Critically Endangered Black-winged Myna Acridotheres melanopterus towards imminent extinction CHRIS R. SHEPHERD , VINCENT NIJMAN , KANITHA KRISHNASAMY , JAMES A. EATON and SERENE C. L. CHNG Summary The Critically Endangered Black-winged Myna Acridotheres melanopterus is being pushed towards the brink of extinction in Indonesia due to continued demand for it as a cage bird and the lack of enforcement of national laws set in place to protect it. The trade in this species is largely to supply domestic demand, although an unknown level of international demand also persists. We conducted five surveys of three of Indonesia’s largest open bird markets (Pramuka, Barito and Jatinegara), all of which are located in the capital Jakarta, between July 2010 and July 2014. No Black-winged Mynas were observed in Jatinegara, singles or pairs were observed during every survey in Barito, whereas up to 14 birds at a time were present at Pramuka. The average number of birds observed per survey is about a quarter of what it was in the 1990s when, on average, some 30 Black-winged Mynas were present at Pramuka and Barito markets. Current asking prices in Jakarta are high, with unbartered quotes averaging USD 220 per bird. Our surveys of the markets in Jakarta illustrate an ongoing and open trade. Dealers blatantly ignore national legislation and are fearless of enforcement actions. Commercial captive breeding is unlikely to remove pressure from remaining wild populations of Black-winged Mynas. Efforts to end the illegal trade in this species and to allow wild populations to recover are urgently needed. -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

Lambusango Forest Conservation Project Research Proposal 2008

Lambusango Forest Research Project OPERATION WALLACEA Research Report 2011 Compiled by Dr Philip Wheeler (email [email protected]) University of Hull Scarborough Campus, Centre for Environmental and Marine Sciences Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Research Sites ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Research activity 2011 ............................................................................................................................ 3 Monitoring bird communities............................................................................................................. 4 Bat community dynamics ................................................................................................................... 9 Monitoring herpetofauna and small mammal communities ........................................................... 11 Butterfly community dynamics ........................................................................................................ 15 Monitoring anoa and wild pig populations ...................................................................................... 19 Habitat associations and sleeping site characteristics -

Bontebok Birds

Birds recorded in the Bontebok National Park 8 Little Grebe 446 European Roller 55 White-breasted Cormorant 451 African Hoopoe 58 Reed Cormorant 465 Acacia Pied Barbet 60 African Darter 469 Red-fronted Tinkerbird * 62 Grey Heron 474 Greater Honeyguide 63 Black-headed Heron 476 Lesser Honeyguide 65 Purple Heron 480 Ground Woodpecker 66 Great Egret 486 Cardinal Woodpecker 68 Yellow-billed Egret 488 Olive Woodpecker 71 Cattle Egret 494 Rufous-naped Lark * 81 Hamerkop 495 Cape Clapper Lark 83 White Stork n/a Agulhas Longbilled Lark 84 Black Stork 502 Karoo Lark 91 African Sacred Ibis 504 Red Lark * 94 Hadeda Ibis 506 Spike-heeled Lark 95 African Spoonbill 507 Red-capped Lark 102 Egyptian Goose 512 Thick-billed Lark 103 South African Shelduck 518 Barn Swallow 104 Yellow-billed Duck 520 White-throated Swallow 105 African Black Duck 523 Pearl-breasted Swallow 106 Cape Teal 526 Greater Striped Swallow 108 Red-billed Teal 529 Rock Martin 112 Cape Shoveler 530 Common House-Martin 113 Southern Pochard 533 Brown-throated Martin 116 Spur-winged Goose 534 Banded Martin 118 Secretarybird 536 Black Sawwing 122 Cape Vulture 541 Fork-tailed Drongo 126 Black (Yellow-billed) Kite 547 Cape Crow 127 Black-shouldered Kite 548 Pied Crow 131 Verreauxs' Eagle 550 White-necked Raven 136 Booted Eagle 551 Grey Tit 140 Martial Eagle 557 Cape Penduline-Tit 148 African Fish-Eagle 566 Cape Bulbul 149 Steppe Buzzard 572 Sombre Greenbul 152 Jackal Buzzard 577 Olive Thrush 155 Rufous-chested Sparrowhawk 582 Sentinel Rock-Thrush 158 Black Sparrowhawk 587 Capped Wheatear -

Supplement - 2016

Green and black poison dart frog Supplement - 2016 Whitley Wildlife Conservation Trust Paignton Zoo Environmental Park, Living Coasts & Newquay Zoo Supplement - 2016 Index Summary Accounts 4 Figures At a Glance 6 Paignton Zoo Inventory 7 Living Coasts Inventory 21 Newquay Zoo Inventory 25 Scientific Research Projects, Publications and Presentations 35 Awards and Achievements 43 Our Zoo in Numbers 45 Whitley Wildlife Conservation Trust Paignton Zoo Environmental Park, Living Coasts & Newquay Zoo Bornean orang utan Paignton Zoo Inventory Pileated gibbon Paignton Zoo Inventory 1st January 2016 - 31st December 2016 Identification IUCN Status Arrivals Births Did not Other Departures Status Identification IUCN Status Arrivals Births Did not Other Departures Status Status 1/1/16 survive deaths 31/12/16 Status 1/1/16 survive deaths 31/12/16 >30 days >30 days after birth after birth MFU MFU MAMMALIA Callimiconidae Goeldi’s monkey Callimico goeldii VU 5 2 1 2 MONOTREMATA Tachyglossidae Callitrichidae Short-beaked echidna Tachyglossus aculeatus LC 1 1 Pygmy marmoset Callithrix pygmaea LC 5 4 1 DIPROTODONTIA Golden lion tamarin Leontopithecus rosalia EN 3 1 1 1 1 Macropodidae Pied tamarin Saguinus bicolor CR 7 3 3 3 4 Western grey Macropus fuliginosus LC 9 2 1 3 3 Cotton-topped Saguinus oedipus CR 3 3 kangaroo ocydromus tamarin AFROSORICIDA Emperor tamarin Saguinus imperator LC 3 2 1 subgrisescens Tenrecidae Cebidae Lesser hedgehog Echinops telfairi LC 8 4 4 tenrec Squirrel monkey Saimiri sciureus LC 5 5 Giant (tail-less) Tenrec ecaudatus LC 2 2 1 1 White-faced saki Pithecia pithecia LC 4 1 1 2 tenrec monkey CHIROPTERA Black howler monkey Alouatta caraya NT 2 2 1 1 2 Pteropodidae Brown spider monkey Ateles hybridus CR 4 1 3 Rodrigues fruit bat Pteropus rodricensis CR 10 3 7 Brown spider monkey Ateles spp. -

Southeast Asia Mega Tour: Singapore/Borneo/Peninsular Malaysia/Halmahera/Sulawesi

Southeast Asia Mega Tour: Singapore/Borneo/Peninsular Malaysia/Halmahera/Sulawesi August 9th-September 30th, 2013 This seven-week tour took us to some of Southeast Asia’s most amazing birding spots, where we racked up some mega targets, saw some amazing scenery, ate some lovely cuisine, and generally had a great time birding. Among some of the fantastic birds we saw were 11 species of pitta, including the endemic Ivory-breasted and Blue-banded Pittas, 27 species of night birds, including the incomparable Satanic Nightjar, Blyth’s, Sunda and Large Frogmouths, and Moluccan Owlet-Nightjar, 14 species of cuckooshrikes, 15 species of kingfishers, and some magical gallinaceous birds like Mountain Peacock- Pheasant, Crested Fireback, and the booming chorus of Argus Pheasant. 13 species of Hornbills were seen, including great looks at Helmeted, White-crowned, Plain-pouched, and Sulawesi. Overall we saw 134 endemic species. Singapore The tour started with some birding around Singapore, and at the Central Catchment Reservoir we started off well with Short-tailed Babbler, Chestnut-bellied Malkoha, Banded Woodpecker, Van Hasselt’s Sunbird, and loads of Pink-necked Green Pigeon. Bukit Batok did well with Straw-headed Bulbul, Common Flameback, and Laced Woodpecker, as well as a particularly obliging group of White- crested Laughingthrush. Borneo We then flew to Borneo, where we began with some local birding along the coast, picking up not only a number of common species of waterbirds but also a mega with White-fronted (Bornean) Falconet. We www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT Southeast Asia Mega Tour: Aug - Sep 2013 ended the day at some rice paddies, where we found Buff-banded Rail and Watercock among several marsh denizens.