The Pattern of Urban Life in Hong Kong: a District Level Community Study of Sham Shui Po

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong Public Opinion Program of Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute

Hong Kong Public Opinion Program of Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute PopPanel Research Report No. 21 cum Community Democracy Project Research Report No. 18 cum Community Health Project Research Report No. 14 Survey Date: 7 May to 12 May 2020 Release Date: 13 May 2020 Copyright of this report was generated by the Hong Kong Public Opinion Program (HKPOP) and opened to the world. HKPOP proactively promotes open data, open technology and the free flow of ideas, knowledge and information. The predecessor of HKPOP was the Public Opinion Programme at The University of Hong Kong (HKUPOP). “POP” in this publication may refer to HKPOP or HKUPOP as the case may be. 1 HKPOP Community Health Project Report No. 14 Research Background Initiated by the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute (HKPORI), the “Community Integration through Cooperation and Democracy, CICD” Project (or the “Community Democracy Project”) aims to provide a means for Hongkongers to re-integrate ourselves through mutual respect, rational deliberations, civilized discussions, personal empathy, social integration, and when needed, resolution of conflicts through democratic means. It is the rebuilding of our Hong Kong society starting from the community level following the spirit of science and democracy. For details, please visit: https://www.pori.hk/cicd. The surveys of Community Democracy (CD) Project officially started on 3 January 2020, targeting members of “HKPOP Panel” established by HKPORI in July 2019, including “Hong Kong People Representative Panel” (Probability-based Panel) and “Hong Kong People Volunteer Panel” (Non-probability-based Panel). This report also represents Report No. 21 under HKPOP Panel survey series, as well as Report No. -

Rsps of the Second Phase of the Pilot Scheme in Kwun Tong District

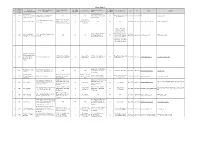

Sham Shui Po District Name of Name of Recognised Service Address of Day Care No. of Day Address of Home Care No. of Home S/N (location of Serving District(s) Serving District(s) Tel Fax Email Website Agency/Organisation Provider Centre Care Places Office Care Places centre) Association for Unit 207-212, Block 44, Association for Engineering and Wong Tai Sin, Sham Shui 1 SSP Engineering and Medical NA NA NA Podium Floor, Shek Kip Mei 10 2779 8333 2779 8821 NA www.emv.org.hk Medical Volunteer Services Po, Kowloon City Volunteer Services Estate, Kowloon Unit 110-113, G/F., Lai Lo Sham Shui Po, Caritas Mutual Help Project (Day 2 SSP Caritas - Hong Kong House, Lai Kok Estate, 24 Kowloon City, Yau NA NA NA 2387 0966 2387 0070 [email protected] www.caritasse.org.hk Care Centre) Cheung Sha Wan, Kowloon Tsim Mong Eastern, Wan Chai, Central & Western, Southern, Kwun Tong, Unit B & D, 8/F, D2 Place 2, Wong Tai Sin, Sai Kung, Care U Professional Care U Professional Nursing Service 2628 7020 / 3 SSP NA NA NA 15 Cheung Shun Street, 50 Sham Shui Po, Kowloon 2628 3002 [email protected] www.careu.com.hk Nursing Service Limited Limited# 6737 1999 Cheung Sha Wan, KLN City, Yau Tsim Mong, Sha Tin, Tai Po, North, Kwai Tsing, Tsuen Wan, Tuen Mun, Yuen Long Hong Kong Baptist Mr. & Mrs. Au Shue Hung 1/F, No. 55 Cornwall Street, Sham Shui Po, 1/F, No. 55 Cornwall Street, Wong Tai Sin, Sham Shui 4 SSP Rehabilitation And The Wonderland Day Centre 20 40 2776 8338 2311 9122 [email protected] http://www.ashrh.org.hk/ Kowloon Tong, Kowloon Kowloon City Kowloon Tong, Kowloon Po, Kowloon City Healthcare Home Limited Room 1, G/F, On Tin House, Hong Kong Christian Shamshuipo Integrated Home Care 5 SSP NA NA NA Pak Tin Estate, Sham Shui 30 Shamshuipo, Kwai Tsing 6756 5789 2778 1129 [email protected] www.hkcs.org Service Service Team - Wonderful Care# Po, Kowloon Hong Kong Young Room 215-216, 2/F, No. -

Egn201014152134.Ps, Page 29 @ Preflight ( MA-15-6363.Indd )

G.N. 2134 ELECTORAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION (ELECTORAL PROCEDURE) (LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL) REGULATION (Section 28 of the Regulation) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BY-ELECTION NOTICE OF DESIGNATION OF POLLING STATIONS AND COUNTING STATIONS Date of By-election: 16 May 2010 Notice is hereby given that the following places are designated to be used as polling stations and counting stations for the Legislative Council By-election to be held on 16 May 2010 for conducting a poll and counting the votes cast in respect of the geographical constituencies named below: Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency LC1 A0101 Joint Professional Centre Hong Kong Island Unit 1, G/F., The Center, 99 Queen's Road Central, Hong Kong A0102 Hong Kong Park Sports Centre 29 Cotton Tree Drive, Central, Hong Kong A0201 Raimondi College 2 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0301 Ying Wa Girls' School 76 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0401 St. Joseph's College 7 Kennedy Road, Central, Hong Kong A0402 German Swiss International School 11 Guildford Road, The Peak, Hong Kong A0601 HKYWCA Western District Integrated Social Service Centre Flat A, 1/F, Block 1, Centenary Mansion, 9-15 Victoria Road, Western District, Hong Kong A0701 Smithfield Sports Centre 4/F, Smithfield Municipal Services Building, 12K Smithfield, Kennedy Town, Hong Kong Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency A0801 Kennedy Town Community Complex (Multi-purpose -

List of Clinics Coordinated by the Home Affairs Department to Provide Injectable Inactivated Influenza Vaccines Under the Special Arrangement

List of clinics coordinated by the Home Affairs Department to provide injectable inactivated influenza vaccines under the Special Arrangement Hong Kong District Name of Clinic Address Enquiry phone number No clinic providing service in this district List of clinics coordinated by the Home Affairs Department to provide injectable inactivated influenza vaccines under the Special Arrangement Kowloon District Name of Clinic Address Enquiry phone number Shop 11, 1-7 Wu Kwong Street, Leung Shu Piu 2954 2661 HUNG HOM, KOWLOON Kowloon City Lok Sin Tong Chan Kwong Hing G/F, 48 Junction Road, 2383 1470 Memorial Primary Health Centre KOWLOON CITY, KOWLOON Room A, G/F, 3 Tsui Ping Road, Christian Family Service Centre 2950 8105 KWUN TONG, KOWLOON Kwun Tong Shop 204, G/F, Tak King House, Tak Hong Family Medical Centre 2709 6677 Tak Tin Estate, LAM TIN, KOWLOON Sham Shui Po District Council Po Shop 101, Mei Kwai House, Shek Kip Mei Estate, Sham Shui Po Leung Kuk Shek Kip Mei Community 2390 2711 13 Pak Tin Street, SHAM SHUI PO, KOWLOON Services Centre (Medical Services) G/F, Unit C, Sik Sik Yuen Social Services Complex, Wong Tai Sin Sik Sik Yuen Clinic 2328 4929 38 Fung Tak Road, WONG TAI SIN, KOWLOON The Lok Sin Tong Flat A&B, 3/F, 688 Shanghai Street, Yau Tsim Mong 2391 1073 Chan Cho Chak Polyclinic Mongkok MONGKOK, KOWLOON List of clinics coordinated by the Home Affairs Department to provide injectable inactivated influenza vaccines under the Special Arrangement New Territories District Name of Clinic Address Enquiry phone number Shop No.9, 1/F, -

Electoral Affairs Commission Report

i ABBREVIATIONS Amendment Regulation to Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) Cap 541F (District Councils) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 Amendment Regulation to Particulars Relating to Candidates on Ballot Papers Cap 541M (Legislative Council) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 Amendment Regulation to Electoral Affairs Commission (Financial Assistance for Cap 541N Legislative Council Elections) (Application and Payment Procedure) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 APIs announcements in public interest APRO, APROs Assistant Presiding Officer, Assistant Presiding Officers ARO, AROs Assistant Returning Officer, Assistant Returning Officers Cap, Caps Chapter of the Laws of Hong Kong, Chapters of the Laws of Hong Kong CAS Civil Aid Service CC Complaints Centre CCC Central Command Centre CCm Complaints Committee CE Chief Executive CEO Chief Electoral Officer CMAB Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau (the former Constitutional and Affairs Bureau) D of J Department of Justice DC, DCs District Council, District Councils DCCA, DCCAs DC constituency area, DC constituency areas DCO District Councils Ordinance (Cap 547) ii DO, DOs District Officer, District Officers DPRO, DPROs Deputy Presiding Officer, Deputy Presiding Officers EAC or the Commission Electoral Affairs Commission EAC (EP) (DC) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) (District Councils) Regulation (Cap 541F) EAC (FA) (APP) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Financial Assistance for Legislative Council Elections and District Council Elections) (Application and Payment -

Mei Ho House Hong Kong Spirit Learning Project School Guided

The Hong Kong Jockey Club Community Project Grant: Mei Ho House Hong Kong Spirit Learning Project School Guided Tour Application Form School Name:___________________________________________ Contact Teacher:_________________ School telephone No.: ___________ Email:____________________________ Mobile. :_____________________ No. of students:_______ Form:_______ Reservation Date:___________________ am(start@10:45am) / pm (start@2:00pm)* Guide Teacher:_____________________ Mobile:_________________ (If different from above) Language*: English / Cantonese Number of Accompanying Teacher: ________ Guided Tour Mode:(Please choose "On Site Tour" below if it is your 1st choice, and "Online Tour" as 2nd choice. If you do not have any 2nd choice, please choose “Nil”.) 1st choice*: On Site Tour / Online Tour 2nd choice*: On Site Tour / Online Tour / Nil Related Subject: ____________ Related Course: ________________ Student’s Learning Characteristics: _________________________________________________________ Purpose of Visit: _______________________________________________________________________ Where did you learn about this school guided tour? Mail website media teachers Other:_____________ A Whatsapp group is opened for communication (in Cantonese), do you want to join? Yes No *please choose one Details of the School Guided Tour Required 1. Visit of Mei Ho House (1 hour) Optional Interactive workshop 1. Alumni story sharing (about half hour) 2. Nostalgic games (about half hour) 3. Hostel room visit (10 students per group, each group per 5-10 minutes) -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 16 December 2020 the Council Met at Eleven O'clock

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 16 December 2020 2375 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 16 December 2020 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS REGINA IP LAU SUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PAUL TSE WAI-CHUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL TIEN PUK-SUN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEVEN HO CHUN-YIN, B.B.S. 2376 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 16 December 2020 THE HONOURABLE FRANKIE YICK CHI-MING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE YIU SI-WING, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE MA FUNG-KWOK, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAN-PAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG CHE-CHEUNG, S.B.S., M.H., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALICE MAK MEI-KUEN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE KWOK WAI-KEUNG, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHRISTOPHER CHEUNG WAH-FUNG, S.B.S., J.P. -

126 Chapter 19 SWD – Central and Islands 4/F, Harbour Building 2852

SWD – Central and Islands 4/F, Harbour Building 2852-3137 Integrated Family 38 Pier Road, Central Service Centre Hong Kong SWD – High Street G/F, Sai Ying Pun 2857-6867 Integrated Family Community Complex Service Centre 2 High Street, Sai Ying Pun Hong Kong SWD – Aberdeen Unit 2, G/F, Pik Long House 2875-8685 Integrated Family Shek Pai Wan Estate Service Centre Aberdeen, Hong Kong The Hong Kong Catholic G/F, La Maison Du Nord 2810-1105 Marriage Advisory Council 12 North Street – Grace and Joy Integrated Kennedy Town, Hong Kong Family Service Centre 126 Chapter 19 Caritas – Hong Kong – 3/F & 5/F, Caritas Jockey Club 2555-1993 Caritas Integrated Family Aberdeen Social Centre Service Centre – Aberdeen 20 Tin Wan Street (Tin Wan / Pokfulam) Aberdeen, Hong Kong The Neighbourhood 1/F, Carpark 1 3141-7107 Advice-Action Council Yat Tung Estate, Tung Chung – The Neighbourhood Lantau Island Advice-Action Council Tung Chung Integrated Services Centre Hong Kong Sheng Kung Shop 201, 2/F 2525-1929 Hui Welfare Council Fu Tung Shopping Centre Limited – Hong Kong Fu Tung Estate Sheng Kung Hui Tung Tung Chung, Lantau Island Chung Integrated Services SWD – Causeway Bay 2/F, Causeway Bay 2895-5159 Integrated Family Community Centre Service Centre 7 Fook Yum Road North Point, Hong Kong SWD – Quarry Bay 2/F & 3/F, The Hong Kong 2562-4783 Integrated Family Federation of Youth Groups Service Centre Building, 21 Pak Fuk Road North Point, Hong Kong SWD – Chai Wan (West) Level 4, Government Office 2569-3855 Integrated Family New Jade Garden Service Centre 233 Chai -

Hansard (English)

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 26 January 2011 5291 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 26 January 2011 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 5292 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 26 January 2011 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

Heritage Impact Assessment on Chai Wan Factory Estate at No. 2 Kut Shing Street, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Heritage Impact Assessment on Chai Wan Factory Estate at No. 2 Kut Shing Street, Chai Wan, Hong Kong April 2013 HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT ON CHAI WAN FACTORY ESTATE April 2013 Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge the permission given by the following organizations and person for the use of their records, maps and photos in the report: . Antiquities and Monuments Office . Architectural Services Department . Hong Kong Housing Authority . Information Services Department . Public Records Office . Survey & Mapping Office, Lands Department i Research Team Team Members Position Prof. HO Puay-peng Team leader MA (Hons), DipArch (Edin.), PhD (London), RIBA Director, CAHR, CUHK Professor, Department of Architecture, CUHK Honorary Professor, Department of Fine Art, CUHK Mr. LO Ka Yu, Henry Project Manager BSSc (AS), MArch, MPhil (Arch), HKICON Associate Director, CAHR, CUHK Ms. HO Sum Yee, May Conservation Architect BSSc (AS), MArch, PDip (Cultural Heritage Management), MSc (Conservation), Registered Architect, HKIA, HKICON Conservation Architect, CAHR, CUHK Ms. NG Wan Yee, Wendy Research Officer BA (AS), MSc (Conservation of the Historic Environment), HKICON Research Project Officer, CAHR, CUHK Ms. LAM Sze Man, Heidi Researcher BA (History) Research Assistant, CAHR, CUHK Ms. YUEN Ming Shan, Connie Researcher MA (Edin.), MPhil (Cantab) Research Assistant, CAHR, CUHK ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Heritage Impact Assessment on Chai Wan Factory Estate ......................................................................... i Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................................... -

Shek Kip Mei Estate Phase 3 – Shop

HONG KONG HOUSING AUTHORITY Special Conditions of Tender Shek Kip Mei Estate Phase 3 – Shop Tenders by way of RENTAL TENDERING are invited for the 3-year tenancy of the following premises located in Shek Kip Mei Estate, Sham Shui Po, Kowloon. Approximate Reference Rent Shop No. Area in m2 Trade (HK$) Mei Kwai House No. G08 90 Electrical, Video and Audio 45,000 Equipment The monthly rent (exclusive of rates) for the above premises is subject to tender. 2. Tenderers are reminded that the tenancy offered will be for a fixed term of 3 years with no option to renew. 3. Only the designated trade will be considered. Tendered rent will be final and not subject to negotiation. Tenderers shall tender monthly fixed rent for the whole lease term of 3 years. 4. Tenderers should note that under the Tenancy Agreement, either party may terminate the tenancy by giving to the other at least three calendar months’ notice in writing. However, in case of breach of any of the conditions contained in the Tenancy Agreement by the tenant, the Hong Kong Housing Authority (HA) shall be entitled to determine the tenancy by giving to the tenant at least one calendar month’s notice in writing. For the avoidance of doubt, where HA invokes section 19(1)(b) of the Housing Ordinance (Cap.283) to terminate the tenancy, the period for the notice to quit issued under that section shall be 1 calendar month. 5. The stated area of the premises is approximate only and no warranty is made as to its precise accuracy. -

2016 Legislative Council General Election Summary on Free Postage for Election Mail 1

2016 Legislative Council General Election Summary on Free Postage for Election Mail 1. Conditions for Free Postage (i) A list of candidate(s) for a Geographical Constituency or the District Council (Second) Functional Constituency, or a candidate for a Functional Constituency who is validly nominated is permitted to post one letter to each elector of the constituency for which the list / or the candidate is nominated free of postage. (ii) Specifically, the letter must: (a) be posted in Hong Kong; (b) contain materials relating only to the candidature of the candidate or candidates on the list, and in the case of joint election mail, also contain materials relating only to the candidature of the other candidate(s) or list(s) of candidate(s) set out in the “Notice of Posting of Election Mail”, at this election concerned; (c) not exceed 50 grams in weight; and (d) be not larger than 175 mm x 245 mm and not smaller than 90 mm x 140 mm in size. (iii) As a general requirement, a candidate should publish election advertisements in accordance with all applicable laws and the “Guidelines on Election-related Activities in respect of the Legislative Council Election”. Hence, election advertisements sent by a candidate through free postage should not contain any unlawful content. (iv) If the name, logo or pictorial representation of a person or an organisation, as the case may be, is included in the election mail, and the publication is in such a way as to imply or to be likely to cause electors to believe that the candidate(s) has/have the support of the person or organisation concerned, the candidate(s) should ensure that prior written consent has been obtained from the person or organisation concerned.