The Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park: Whose Values, Whose Benefits? Thesis Summary Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Area Guide Brochure

GALLIONS POINT AT ROYAL ALBERT WHARF | E16 AREA GUIDE Photography of show home at Gallions point. SITUATED IN EAST LONDON’S ROYAL DOCKS. Gallions Point is perfectly positioned to take advantage of living in one of the world’s greatest cities. With its rich history and culture, unparalleled shopping opportunities, world-class restaurants, award-winning green spaces, and some of the world’s most iconic buildings and landmarks, the capital has it all in abundance. In this guide you’ll find just a few of the places that make London such an incredible place to live, with a list of amenities and services that we think you’ll find useful as well. Computer generated image of Gallions Point are indicative only. BLACKWELL TUNNEL START YOUR The Blackwall Tunnel is a pair of road tunnels underneath the River Thames in east ADVENTURE AT London, England linking the London Borough of Tower Hamlets with the Royal GALLIONS POINT Borough of Greenwich. EMIRATES AIR LINE Emirates Air Line crosses the River Thames between Greenwich Peninsula and the Royal Docks, just five minutes from the O2 by North Greenwich Tube station. Cabins arrive every 30 seconds and flights are approximately 10 minutes each way. SANTANDER CYCLES DLR – LONDON BIKE HIRE GALLIONS REACH BOROUGH BUSES You can hire a bike from as With the station literally London’s iconic double- little as £2. Simply download at your doorstep, your decker buses are a quick, the Santander Cycles app destination in London is convenient and cheap way or go to any docking station easily in reach. -

Making a Home in Silvertown – Transcript

Making a Home in Silvertown – Transcript PART 1 Hello everyone, and welcome to ‘Making a Home in Silvertown’, a guided walk in association with Newham Heritage Festival and the Access and Engagement team at Birkbeck, University of London. My name’s Matt, and I’m your tour guide for this sequence of three videos that lead you on a historic guided walk around Silvertown, one of East London’s most dynamic neighbourhoods. Silvertown is part of London’s Docklands, in the London Borough of Newham. The area’s history has been shaped by the River Thames, the Docks, and the unrivalled variety of shipping, cargoes and travellers that passed through the Port of London. The walk focuses on the many people from around the country and around the world who have made their homes here, and how residents have coped with the sometimes challenging conditions in the area. It will include plenty of historical images from Newham’s archives. There’s always more to explore about this unique part of London, and I hope these videos inspire you to explore further. The reason why this walk is online, instead of me leading you around Silvertown in person, is that as we record this, the U.K. has some restrictions on movement and public assembly due to the pandemic of COVID-19, or Coronavirus. So the idea is that you can download these videos onto a device and follow their route around the area, pausing them where necessary. The videos are intended to be modular, each beginning and ending at one of the local Docklands Light Railway stations. -

The Park Keeper

The Park Keeper 1 ‘Most of us remember the park keeper of the past. More often than not a man, uniformed, close to retirement age, and – in the mind’s eye at least – carrying a pointed stick for collecting litter. It is almost impossible to find such an individual ...over the last twenty years or so, these individuals have disappeared from our parks and in many circumstances their role has not been replaced.’ [Nick Burton1] CONTENTS training as key factors in any parks rebirth. Despite a consensus that the old-fashioned park keeper and his Overview 2 authoritarian ‘keep off the grass’ image were out of place A note on nomenclature 4 in the 21st century, the matter of his disappearance crept back constantly in discussions.The press have published The work of the park keeper 5 articles4, 5, 6 highlighting the need for safer public open Park keepers and gardening skills 6 spaces, and in particular for a rebirth of the park keeper’s role. The provision of park-keeping services 7 English Heritage, as the government’s advisor on the Uniforms 8 historic environment, has joined forces with other agencies Wages and status 9 to research the skills shortage in public parks.These efforts Staffing levels at London parks 10 have contributed to the government’s ‘Cleaner, Safer, Greener’ agenda,7 with its emphasis on tackling crime and The park keeper and the community 12 safety, vandalism and graffiti, litter, dog fouling and related issues, and on broader targets such as the enhancement of children’s access to culture and sport in our parks The demise of the park keeper 13 and green spaces. -

CONTINUOUS PRODUCTIVE URBAN LANDSCAPES Cpul-FM.Qxd 02/01/2005 9:07 PM Page Ii Cpul-FM.Qxd 02/01/2005 9:07 PM Page Iii

Cpul-FM.qxd 02/01/2005 9:07 PM Page i CONTINUOUS PRODUCTIVE URBAN LANDSCAPES Cpul-FM.qxd 02/01/2005 9:07 PM Page ii Cpul-FM.qxd 02/01/2005 9:07 PM Page iii CONTINUOUS PRODUCTIVE URBAN LANDSCAPES: DESIGNING URBAN AGRICULTURE FOR SUSTAINABLE CITIES André Viljoen Katrin Bohn Joe Howe AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON • NEW YORK • OXFORD PARIS • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Architectural Press is an imprint of Elsevier Cpul-FM.qxd 02/01/2005 9:07 PM Page iv Architectural Press An imprint of Elsevier Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington, MA 01803 First published 2005 Copyright © 2005, André Viljoen. All rights reserved. The right of André Viljoen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP.Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science and Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK; phone: ϩ44-0-1865-843830; fax: ϩ44-0-1865-853333; e-mail: [email protected]. -

YPG2EL Newspaper

THE YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO EAST LONDON East London places they don’t put in travel guides! Recipient of a Media Trust Community Voices award A BIG THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS This organisation has been awarded a Transformers grant, funded by the National Lottery through the Olympic Lottery Distributor and managed by ELBA Café Verde @ Riverside > The Mosaic, 45 Narrow Street, Limehouse, London E14 8DN > Fresh food, authentic Italian menu, nice surroundings – a good place to hang out, sit with an ice cream and watch the fountain. For the full review and travel information go to page 5. great places to visit in East London reviewed by the EY ETCH FO P UN K D C A JA T I E O H N Discover T B 9 teenagers who live there. In this guide you’ll find reviews, A C 9 K 9 1 I N E G C N YO I U E S travel information and photos of over 200 places to visit, NG PEOPL all within the five London 2012 Olympic boroughs. WWW.YPG2EL.ORG Young Persons Guide to East London 3 About the Project How to use the guide ind an East London that won’t be All sites are listed A-Z order. Each place entry in the travel guides. This guide begins with the areas of interest to which it F will take you to the places most relates: visited by East London teenagers, whether Arts and Culture, Beckton District Park South to eat, shop, play or just hang out. Hanging Out, Parks, clubs, sport, arts and music Great Views, venues, mosques, temples and churches, Sport, Let’s youth centres, markets, places of history Shop, Transport, and heritage are all here. -

Article009.Pdf (3.389Mb)

Plan Building a Town Centre in London Js Royal Docks by Michel Trocme Corporation to lead a more socially, envi communicated in the brief) did not play a A HISTORIC SHIFT is occurring in London as its ronmentally and economically sustainable significant role in the development of the centre of gravity moves eastwards. The financial regeneration of London's waterfront design. The very nature of the competition district of London's "New East," Canary Wharf, has assets. The LDA, working closely with the process inhibited any consultation with already generated 50,000 jobs and will double that London Borough of Newham , have pro adjacent residents and business interests. ceeded with an integrated, sustainable number in the next few years. The surrounding Isle economic and social framework for the The big moves of Dogs is home to 80,000 people. The eastward Royal Docks as a residential community, a A focal point of our team's development expansion has now reached the Royal Docks, which major employment location, and an proposal is the National Aquarium, an were at the heart ofBritain's international trade for attractive leisure destination. Great care institution of international drawing power well over 100 years and form the last large land asset has been taken to make multifaceted link (attracting 1.5 million visitors a year) ages between the evolving Silvertown which will create strong site recognition. in the Docklands. community and the established communi Additional destination uses, culture and ties of Canning Town and North entertainment around the dock will ensure Situated on the north bank of the River Woolwich. -

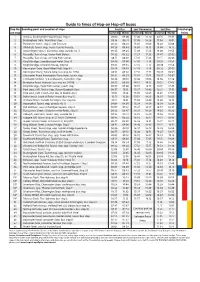

Guide to Times of Hop-On Hop-Off Buses Stop No

Guide to times of Hop-on Hop-off buses Stop No. Boarding point and Location of stops First Bus Last Panoramic Last Bus Interchange (see map) Summer Winter Summer Winter Summer Winter Points 1 Victoria, Buckingham Palace Road, Stop 8. 09:00 09:00 17:00 16:30 20:15 19:45 2 Buckingham Gate, Tourist bus stop. 08:16 08:31 17:08 16:38 17:56 18:01 3 Parliament Street, stop C, HM Treasury. 08:23 08:38 16:03 16:08 18:03 18:08 4 Whitehall, Tourist stop, Horse Guards Parade. 08:28 08:43 16:08 16:13 18:08 18:13 5 Lower Regent Street, tourist bus stop, outside no. 11. 09:25 09:25 17:20 17:25 19:40 19:55 6 Piccadilly, Tourist stop, Green Park Station. 09:32 09:32 17:27 17:32 19:47 20:02 7 Piccadilly, Tourist stop, at Hyde Park Corner. 08:11 08:26 17:31 17:36 19:51 20:06 8 Knightsbridge, Lanesborough Hotel. Stop 13. 09:40 09:40 17:40 17:10 20:23 19:53 9 Knightsbridge, At Scotch House, Stop KE. 09:45 09:45 17:45 17:15 20:28 19:58 10 Kensington Gore, Royal Albert Hall, Stop K3. 09:49 09:49 17:49 17:19 20:32 20:02 11 Kensington Road, Palace Gate, bus stop no. 11150. 08:31 08:36 17:51 17:21 20:34 20:04 12 Gloucester Road, Kensington Plaza Hotel, tourist stop. 08:34 08:39 17:54 17:24 20:37 20:07 13 Cromwell Gardens, V & A Museum, tourist bus stop. -

Residential-Led Development Opportunity

RESIDENTIAL-LED DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY WEST SILVERTOWN PLACE 278-291 NORTH WOOLWICH ROAD, SILVERTOWN, E16 2BB RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY | WEST SILVERTOWN PLACE OPPORTUNITY SUMMARY WEST SILVERTOWN PLACE IS A FREEHOLD RESIDENTIAL-LED DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY WITH EXISTING INCOME UNTIL AUGUST 2022. • Freehold site extending to approximately 0.62 acres (0.25 hectares). • Favourable pre-app response from LB Newham for a residential-led scheme comprising 72 residential apartments and ground floor B1 (office) commercial space. THE SITE • Currently let to two tenants with a total passing rent of £166,000 pa with VP available from August 2021 and August 2022 respectively. • West Silvertown Place is within an area that has experienced significant regeneration, including Ballymore’s Royal Wharf scheme with a host of retail and leisure offerings located directly opposite the site. • West Silvertown DLR Station is located 0.3 miles to the west, Custom House (Crossrail) is located 0.8 miles to the north and London City Airport is situated 1.2 miles to the east. • Offers invited on a Subject to Planning basis in excess of £5,750,000. OPPORTUNITY LOCAL SURROUNDING TRANSPORT & SITE PLANNING AND FURTHER SUMMARY AREA CONTEXT CONNECTIVITY DESCRIPTION DEVELOPMENT INFORMATION RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY | WEST SILVERTOWN PLACE THE LOCAL AREA West Silvertown Place is located within the London Borough WINDJAMMER PUB THAMES BARRIER PARK of Newham. The Site can be found on the corner of North Woolwich Road, Boxley Street and Fort Street and is situated directly opposite Ballymore & Oxley’s Royal Wharf scheme. The Royal Wharf scheme will provide a total of 3,385 residential units and a variety of retail and leisure occupiers including the riverside pub The Windjammer, Sainsbury’s Local and a number of coffee shops and café’s including Triple Two and Starbucks. -

The Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects Town Planning Conference, London, 10-15 October 1910

The Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects Town Planning Conference, London, 10-15 October 1910 Introduction by William Whyte Routledge R Taylor & Francis Croup LONDON AND NEW YORK CONTENTS. Portraits : Hon. President, President, Secretary-General—Frontispiece Preface [John W. Simpson] ....... iii PART I. RECORD OF THE CONFERENCE. PAGE Portraits of Chief Officials of Sub-Committees, &c. plate Organisation—Membership—Designs for Conference Badge, Poster, Handbook cover, Banquet Card—Railway Facilities—Receptions—Exhibitions—Professor Geddes' Exhibit—Order of Procedure at Meetings—Programme— Letter from the American Civic Association I Committee of Patronage . .12 Executive Committee . .13 Committees of the Executive . 14 Honorary Interpreters . .14 Representatives of Corporations, Councils, and Societies . 16 List of Members . -3° INAUGURAL MEETING ........ 58 Address by the President, Mr. Leonard Stokes . - 59 Inaugural Address by the Hon. President, the Right Hon. John Burns, M.P. .62 Telegram fromthe King .......75 Vote of Thanks to Mr. Burns [Sir Aston Webb] . 76 VISITS AND EXCURSIONS : Reports— Letchworth Garden City [Courtenay Crickmer] . 77 Hatfield House [J. Alfred Gotch and Harold I. Merriman] 77 Hampton Court Palace [H. P. G. Maule] ...80 Bedford Park, Chiswick [Maurice B. Adams] ...80 L.C.C. Housing Estate, White Hart Lane [W. E. Riley] 82 St'. Paul's, The Tower, St. Bartholomew the Great [Percy W.Lovell] ........82 Greenwich Hospital [F. Dare Clapham] .... 83 Hampstead Garden Suburb [Raymond Unwin] . 83 Bridgewater House and Dorchester House [Septimus War wick] 84 Regent's Park and Avenue Road Estate [H. A. Hall] . 84 Houses of Parliament and Westminster Hall [G. J. T. Reavell] 85 Westminster Abbey 85 Inns of Court [C. -

Ladbroke Grove, Restaurants

16_165454 bindex.qxp 10/16/07 2:09 PM Page 273 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Art museums and galleries, Big Ben, 187 175–180 Big Bus Company, 193 Arts and crafts The Big Draw, 22, 174 Abbeys, 171, 188–189 classes and workshops, 219 Biking, 58, 211 Abney Park Cemetery & Nature shopping for, 225 Billy Elliot, 252 Reserve, 192, 208 Artsdepot, 250 Black Lion, 200 Accessorize, 232 ATMs, 15, 16, 63 Blood Brothers, 252 Accommodations, 65–98. See Aylesbury, 265–269 Bloody Tower (Tower of also Accommodations Index London), 153 near airports, 66–67 Bloomsbury, 50 best bets, 3–8 aby equipment, 59 accommodations, 74–75 Central London, 67–78 B Baby gifts, 238–239 restaurants, 110 Chatham, 271 Babygroove, 255 walking tour, 196–197 Chiltern Hills, 268 Baby Show London, 22 Bluewater Mall (Kent), 240 East London, 92–96 Babysitters, 59–60 Boating, 217, 218 North London, 96–98 Bakeries, 234 Boat trips and cruises, with pools, 8, 72 Balham, 53 180–181, 194 pricing, 66 accommodations, 89 Boveney Lock, 263 reservations, 66–67 restaurants, 131–133 canal, 180–181 south of the River, 86–92 Ballet, 212, 252, 255–256 the Continent, 35, 36 surfing for, 28 Ballooning, 213 Greenwich, 148, 150 tipping, 64 Bank of England Museum, 157 Herne Bay, 271 west of the Center, 78–86 Barbican Centre, 54, 243, 246 Windsor, 263 Whitstable, 271 Barrie, J. M., 37, 195–196, Books, recommended, 36–37 Windsor, 264–265 209–210 Bookstores, 225–226 youth hostels, 66, 90–91 Basketball, 258 story hours, 260 Addresses, finding an, 49 Battersea, -

Thames-Path-South-Section-4.Pdf

Transport for London.. Thames Path south bank. Section 4 of 4. Thames Barrier to River Darent. Section start: Thames Barrier. Nearest station Charlton . to start: Section finish: River Darent. Nearest stations Slade Green . to finish: Section distance: 11 miles (17.5 kilometres) . Introduction. Beyond the Thames Barrier, the route is waymarked with the Thames Barge symbol rather than the National Trail acorn. This is because the Thames Path National Trail officially ends at the Thames Barrier but it is possible to continue the walk as far as the boundary with Kent. There is a continuous riverside path all the way along the Thames as far as the River Darent on the Bexley boundary with Dartford. There are plans to extend further through the Kent side of the Thames Gateway. Eventually it is hoped the 'Source to Sea' Path will materialise on both sides of the Thames. The working river displays all the muscularity of its ancient history, built up by hard graft since Henry VIII's royal dockyard at Woolwich was established to build a new generation of naval warships. Woolwich Arsenal grew up alongside to supply munitions, and Thamesmead was built on a vast network of 'tumps' to contain explosions, some of which can still be seen. Across the river, equally vast operations are visible where giant cranes move and shape the last landfill into new hillsides and Ford at Dagenham's wind turbines symbolise the post-industrial end of oil. The cargo ships now come only as far as Tilbury and the vast sea container ports on the north side of the river; whereas Erith with its pier, once a Victorian pleasure resort, retains a seaside feel. -

Conservation and Foraging Ecology of Bumble Bees In

Conservation and Foraging Ecology of Bumble Bees in Urban Environments Roselle E. Chapman A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of London. Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London & University College London. April 2004 1 UMI Number: U602843 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602843 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The decline of British bumble bees has been attributed to the loss of their habitat through the intensification of agricultural practices. In the quest for information of use to bumble bee conservation the potential of our flower-rich cities has been overlooked. The overall aim of this study was to determine the status and foraging requirements of bumble bees in the urban environment provided by the city of London, U.K. My principal findings are as follows. Six common species and three rare species were identified. The greatest diversity of Bombus species was found in the east of London. Garden and wasteland habitats attracted the greatest abundance of workers and diversity of Bombus species.