Gila Monster Status, Identification and Reporting Protocol for Observations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prolonged Poststrike Elevation in Tongue-Flicking Rate with Rapid Onset in Gila Monster, <Emphasis Type="Italic">

Journal of Chemical Ecology, Vol. 20. No. 11, 1994 PROLONGED POSTSTRIKE ELEVATION IN TONGUE- FLICKING RATE WITH RAPID ONSET IN GILA MONSTER, Heloderma suspectum: RELATION TO DIET AND FORAGING AND IMPLICATIONS FOR EVOLUTION OF CHEMOSENSORY SEARCHING WILLIAM E. COOPER, JR. I'* CHRISTOPHER S. DEPERNO I and JOHNNY ARNETT 2 ~Department of Biology Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne Fort Wayne. bldiana 46805 2Department of Herpetology Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 (Received May 6, 1994; accepted June 27, 1994) Abstract--Experimental tests showed that poststrike elevation in tongue-flick- ing rate (PETF) and strike-induced chemosensory searching (SICS) in the gila monster last longer than reported for any other lizard. Based on analysis of numbers of tongue-flicks emitted in 5-rain intervals, significant PETF was detected in all intervals up to and including minutes 41~-5. Using 10-rain intervals, PETF lasted though minutes 46-55. Two of eight individuals con- tinued tongue-flicking throughout the 60 rain after biting prey, whereas all individuals ceased tongue-flicking in a control condition after minute 35. The apparent presence of PETF lasting at least an hour in some individuals sug- gests that there may be important individual differences in duration of PETF. PETF and/or SICS are present in all families of autarchoglossan lizards stud- ied except Cordylidae, the only family lacking lingually mediated prey chem- ical discrimination. However, its duration is known to be greater than 2-rain only in Helodermatidae and Varanidae, the living representatives of Vara- noidea_ That prolonged PETF and S1CS are typical of snakes provides another character supporting a possible a varanoid ancestry for Serpentes. -

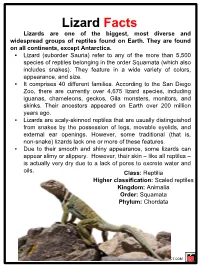

Lizard Facts Lizards Are One of the Biggest, Most Diverse and Widespread Groups of Reptiles Found on Earth

Lizard Facts Lizards are one of the biggest, most diverse and widespread groups of reptiles found on Earth. They are found on all continents, except Antarctica. ▪ Lizard (suborder Sauria) refer to any of the more than 5,500 species of reptiles belonging in the order Squamata (which also includes snakes). They feature in a wide variety of colors, appearance, and size. ▪ It comprises 40 different families. According to the San Diego Zoo, there are currently over 4,675 lizard species, including iguanas, chameleons, geckos, Gila monsters, monitors, and skinks. Their ancestors appeared on Earth over 200 million years ago. ▪ Lizards are scaly-skinned reptiles that are usually distinguished from snakes by the possession of legs, movable eyelids, and external ear openings. However, some traditional (that is, non-snake) lizards lack one or more of these features. ▪ Due to their smooth and shiny appearance, some lizards can appear slimy or slippery. However, their skin – like all reptiles – is actually very dry due to a lack of pores to excrete water and oils. Class: Reptilia Higher classification: Scaled reptiles Kingdom: Animalia Order: Squamata Phylum: Chordata KIDSKONNECT.COM Lizard Facts MOBILITY All lizards are capable of swimming, and a few are quite comfortable in aquatic environments. Many are also good climbers and fast sprinters. Some can even run on two legs, such as the Collared Lizard and the Spiny-Tailed Iguana. LIZARDS AND HUMANS Most lizard species are harmless to humans. Only the very largest lizard species pose any threat of death. The chief impact of lizards on humans is positive, as they are the main predators of pest species. -

Vernacular Name GILA MONSTER

1/6 Vernacular Name GILA MONSTER GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwestern U.S. and northwestern Mexico. HABITAT Succulent desert and dry sub-tropical scrubland, hillsides, rocky slopes, arroyos and canyon bottoms (mainly those with streams). CONSERVATION STATUS IUCN: Near Threatened (2016). Population Trend: Decreasing. Threats: - illegal exploitation by commercial and private collectors. - habitat destruction due to urbanization and agricultural development. COOL FACTS Their common name “Gila” refers to the Gila River Basin in the southwest U.S. Their skin consists of many round, bony scales, a feature that was common among dinosaurs, but is unusual in today's reptiles. The Gila monster and the Mexican beaded lizard are the only lizards known to be venomous. Both live in North America. Gila monsters are the largest lizards native to the U.S. Gila monsters may bite and not let go, continuing to chew and, thereby, inject more venom into their victims. Venom is released from the venom glands (modified salivary glands) into the lower jaws and travels up grooves on the outside of the teeth and into the victims as the Gila monsters bite. The lizards lack the musculature to forcibly inject the venom; instead the venom is propelled from the gland to the tooth by chewing. Capillary action brings the venom out of the tooth and into the victim. Gila monsters have been observed to flip over while biting the victim, presumably to aid the flow of the venom into the wound. Bites are painful, but rarely fatal to humans in good health. While the bites can overpower predators and prey, they are rarely fatal to humans in good health although humans may suffer pain, edema, bleeding, nausea and vomiting. -

Inventory of Amphibians and Reptiles at Death Valley National Park

Inventory of Amphibians and Reptiles at Death Valley National Park Final Report Permit # DEVA-2003-SCI-0010 (amphibians) and DEVA-2002-SCI-0010 (reptiles) Accession # DEVA- 2493 (amphibians) and DEVA-2453 (reptiles) Trevor B. Persons and Erika M. Nowak Common Chuckwalla in Greenwater Canyon, Death Valley National Park (TBP photo). USGS Southwest Biological Science Center Colorado Plateau Research Station Box 5614, Northern Arizona University Flagstaff, Arizona 86011 May 2006 Death Valley Amphibians and Reptiles_____________________________________________________ ABSTRACT As part of the National Park Service Inventory and Monitoring Program in the Mojave Network, we conducted an inventory of amphibians and reptiles at Death Valley National Park in 2002- 2004. Objectives for this inventory were to: 1) Inventory and document the occurrence of reptile and amphibian species occurring at DEVA, primarily within priority sampling areas, with the goal of documenting at least 90% of the species present; 2) document (through collection or museum specimen and literature review) one voucher specimen for each species identified; 3) provide a GIS-referenced list of sensitive species that are federally or state listed, rare, or worthy of special consideration that occur within priority sampling locations; 4) describe park-wide distribution of federally- or state-listed, rare, or special concern species; 5) enter all species data into the National Park Service NPSpecies database; and 6) provide all deliverables as outlined in the Mojave Network Biological Inventory Study Plan. Methods included daytime and nighttime visual encounter surveys, road driving, and pitfall trapping. Survey effort was concentrated in predetermined priority sampling areas, as well as in areas with a high potential for detecting undocumented species. -

Lizards & Snakes Alive!

Media Inquiries: Aubrey Gaby; Department of Communications March 2010 212-496-3409; [email protected] www.amnh.org LIZARDS & SNAKES: ALIVE! BACK ON VIEW AT THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY MARCH 6–SEPTEMBER 6, 2010 RETURNING EXHIBITION SHOWCASES MORE THAN 60 LIVE LIZARDS AND SNAKES FROM AROUND THE WORLD The real monsters, dragons, and basilisks are back! More than 60 live lizards and snakes from five continents reside in exquisitely prepared habitats. In addition to the live animals, the exhibit uses interactive stations, significant fossils, and an award-winning video to acquaint visitors with the world of the Squamata, the group that includes lizards and snakes. Visitors can learn about chameleons’ ballistic tongues, how basilisks escape from predators by running across water, amazing camouflage of Madagascar geckos, the 3-D thermal vision of rattlesnakes and boas, spitting cobra fangs, blood-squirting Horned Lizards, flying snakes and lizards, and other gravity-defying squamates. Approximately 8,000 species of lizards and snakes have been recognized and new species continue to be discovered. In Lizards & Snakes: Alive! visitors will see 26 species, including crowd favorites such as the Gila Monster, Eastern Water Dragon, Green Basilisk, Veiled Chameleon, Blue-tongued Skink, Rhinoceros Iguana, Eastern Green Mamba, and a fourteen-foot Burmese Python. The Water Monitor habitat is equipped with a Web camera enabling virtual visitors around the globe to observe the daily behavior of one of the largest living species of lizard on Earth. One case in the exhibition includes four species of geckos: Madagascan Giant Day Geckos, Common Leaf- tailed geckos, Lined Leaf-tailed Geckos, and Henkel’s Leaf-tailed Geckos. -

Venomous Reptiles of Nevada

Venomous Reptiles of Nevada Figure 1 The buzz from a rattlesnake can signal a heart stopping adventure to even the most experienced outdoor enthusiast. Figure 2 Authors M. L. Robinson, Area Specialist, Water/Environmental Horticulture, University of Nevada Cooperative Extension Polly M. Conrad, Wildlife Diversity Biologist—Reptiles, Nevada Department of Wildlife Maria M. Ryan, Area Specialist, Natural Resources, University of Nevada Cooperative Extension Updated from G. Mitchell, M.L. Robinson, D.B. Hardenbrook and E.L. Sellars. 1998. What’s the Buzz About Nevada’s Venomous Reptiles? University of Nevada Cooperative Extension—Nevada Department of Wildlife Partnership Publication. FS-98-35. SP 07-07 (Replaces FS-98-35) NEVADA’S REPTILES Approximately 52 species of snakes and lizards share the Nevada landscape with us. Of these, only 12 are considered venomous. Only 6 can be dangerous to people and pets. Encountering them is uncommon because of their body camouflage and secretive nature, which are their first defenses in evading predators. Consider yourself fortunate if you do see one! As with all wildlife, treat venomous reptiles with respect. Reptiles are ectothermic, meaning their body temperature increases or decreases in response to the surrounding environment. They are most active in the spring, summer and early fall when it’s comfortable, short sleeve weather for us. Reptiles usually hibernate, or brumate, in winter in response to colder temperatures. During high summer temperatures in the Mojave Desert, reptiles may spend time underground in order to maintain vital body temperatures. In most cases*, collecting Nevada’s native reptiles is not allowed without the appropriate permit, which is issued by the Nevada Department of Wildlife. -

Enter the Dragon: the Dynamic and Multifunctional Evolution of Anguimorpha Lizard Venoms

Article Enter the Dragon: The Dynamic and Multifunctional Evolution of Anguimorpha Lizard Venoms Ivan Koludarov 1, Timothy NW Jackson 1,2, Bianca op den Brouw 1, James Dobson 1, Daniel Dashevsky 1, Kevin Arbuckle 3, Christofer J. Clemente 4, Edward J. Stockdale 5, Chip Cochran 6, Jordan Debono 1, Carson Stephens 7, Nadya Panagides 1, Bin Li 8, Mary‐Louise Roy Manchadi 9, Aude Violette 10, Rudy Fourmy 10, Iwan Hendrikx 1, Amanda Nouwens 11, Judith Clements 7, Paolo Martelli 12, Hang Fai Kwok 8 and Bryan G. Fry 1,* 1 Venom Evolution Lab, School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St. Lucia QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] (I.K.); [email protected] (T.N.W.J.); [email protected] (B.o.d.B.); [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (N.P.); [email protected] (I.H.) 2 Australian Venom Research Unit, School of Biomedical Sciences, Level 2 Medical Building, University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia 3 Department of Biosciences, College of Science, Swansea University, Swansea SA2 8PP, UK; [email protected] 4 University of the Sunshine Coast, School of Science and Engineering, Sippy Downs, Queensland 4558, Australia; [email protected] 5 Gradient Scientific and Technical Diving, Rye, Victoria 3941, Australia; [email protected] (E.J.S.) 6 Department of Earth and Biological Sciences, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA 92350, USA; [email protected] 7 School of Biomedical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane QLD 4001, Australia; [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (J.C.) 8 Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, Avenida da Universidade, Taipa, Macau; [email protected] (B. -

AMPHIBIANS and REPTILES of ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL MONUMENT Compiled by the Interpretive Staff with Technical Assistance from Dr

AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES OF ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL MONUMENT Compiled by the Interpretive Staff With Technical Assistance From Dr. J . C. McCoy, Carnegie Museum, Pittsburg, Pa. and Dr. Robert C. Stebbins, University of California, Berkeley Comm:m Names Scientific Names Amphibians Class Amphibia Frogs ~ Toads Order Sa.;J.ienta Toads Family Bufonidae Colorado River toad Bufo alvaris (s) Great plains toad nuro co~tus (s) Red- spotted toad Biil'O puncatus (s) Sonora green toad Buf'O retiformis Spadefoot Toads Family Pelobatidae Couch's spadefoot Scaphiopus couchi (8) Reptiles Class Reptilia Turtles Order Testudinata Mud Turtles and Their Allies Family Chelydridae Sonora mud turtle Kinosternon sonorien8e (s) Land Tortoises and Their Allies Family Testudinjdae - -.;.;.;.;;;.;;;;;..--- Desert tortoise Gopherus agassizi Lizards and Snakes Order Squamata Lizards Suborder Sauria Geckos Family Gekkonidae Desert banded gecko Coleoqyx ! . variegatus (s) Iguanids Family Iguanidae Arizona zebra- tailed lizard Callisaurus draconoides ventralis (s) Western collard lizard Crotaphytus collaris bailer) ( s) Long-nosed leopard lizard Crotaphytus ! . wislizeni (s Desert iguana ~saurus d. dorsalis (s) Southern desert horned lizard osoma p!atyrhinos calidiarum Regal horned lizard Phrynosoma solara ( s) Arizona chuckwalla Sauromalus obesus tumidus (s) Desert spi~ lizard SceloEorus m. magister (s) Colorado River tree lizard Urosaurus ornatus symmetricus (s) Desert side-blotched lizard ~ stansburiana stejnegeri (s) Teids Family Teidae Red-backed whiptail Cnemidophorus burti xanthonot us ~) Southern whiptail Cnemidophorus tigris gracilis (6) Venomous Lizards Family Heloderrr~tidae Reticula.te Gila m:mster Heloderma ! .. suspectum (6) Snakes Suborder Serpentes Worm Snakes Family Leptotyphlopidae Southwestern blind snake Leptottphlops h. humilis (s) Boas Family Boidae Desert rosy boa Lichanura trivirgata gracia (s) Colubrids Family Colubridae Arizona glossy snake Arizona elegans noctivaga c. -

Year of the Lizard News No

Year of the Lizard News No. 4 July 2012 V V V V V V V V V V www.YearoftheLizard.org Lizards Across the Land: Federal Agencies’ Role From Alaska to Hawaii to Florida, hundreds of millions of acres of our public lands are held in trust by federal land management agencies. Many of these lands support rich and diverse populations of lizards. The following collection of articles provides a sample of the outstanding scholarly and practical work being conducted on our federal public lands. Biologists at these and other federal agencies are hard at work to answer many important questions regarding A Copper-striped Blue-tailed Skink (Emoia impar) the science of lizard conservation and management and to photographed in Samoa during a USGS field survey. identify and conserve priority habitats for lizards and other Photo: Chris Brown, USGS. native wildlife. “No other landscape in these United States has —Terry Riley, National Park Service, National PARC been more impacted by extinction events and species Federal Agencies Coordinator invasions in historic times than the Hawaiian Islands, with as yet unknown long-term cascading consequences USGS Reveals “Cryptic Extinction” of Pacific to the ecosystem,” said U.S. Geological Survey director Lizard Marcia McNutt. “Today, we close the book on one more animal that is unlikely to ever be re-established in this A species of lizard is now extinct from the Hawaiian fragile island home.” Islands, making it the latest native vertebrate species to “This skink was once common throughout the become extirpated from this tropical archipelago. Hawaiian Islands, and in fact the species can still be The Copper-striped Blue-tailed Skink (Emoia impar) — found on many other island groups in the tropical a sleek lizard with smooth, polished scales and a long, sky- blue tail — was last confirmed in the Na’Pali coast of Kauai continued on p. -

DANGEROUS DESERT DWELLERS? Gila Monsters and Rattlesnakes

National Park Service Tonto U.S. Department of the Interior Tonto National Monument DANGEROUS DESERT DWELLERS? Gila Monsters and Rattlesnakes Over the years, most of us have read books or seen movies and TV shows about the "real" West. In many of these stories, the villains are not men, but reptiles. Gila monsters attack innocent women and children; rattlesnakes lurk behind rocks, waiting to sink their fangs into the unsuspecting hero. Exciting as these tales are, the truth is much more interesting. Gila Monsters Their vision and hearing are good, they are efficient diggers, can climb well, and are adequate swimmers. The Gila monster is one of only two venomous lizards in the world. Its Latin name, Heloderma We think mating takes place in early summer, and a suspectum, refers to the animal’s textured skin and clutch of 2 - 12 eggs is laid in July or August. The suspicions that it might be poisonous. “Gila” may young appear approximately 10 months later. They refer to the fact that they are often seen around the may hatch earlier and overwinter; we don’t know Gila River, or it may be a corruption of Heloderma. much about this part of the life cycle. Hatchlings are about 6" long and weigh approximately one ounce. Gila monsters primarily live in the Sonoran Desert, They reach maturity at 4 - 5 years, and can live to be ranging from sea level to about 5000'. They come 20 - 30. They do not have any definite predators; out of their burrows between March and April, which most literature says they "may" be preyed upon by coincides with the appearance of their preferred prey coyotes and birds of prey. -

Gila Monster Status, Identification and Reporting Protocol for Observations

NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE Southern Region 3373 Pepper Lane, Las Vegas, Nevada 89120 Phone: 702-668-3839 or 702-486-5127; Fax: 702-486-5133 5 February 2020 GILA MONSTER STATUS, IDENTIFICATION AND REPORTING PROTOCOL FOR OBSERVATIONS Status The Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) is secretive, difficult to detect, and seemingly rare relative to other species. These attributes led the State of Nevada decades ago to classify the species as Protected (Nevada Administrative Code 503.080). Their populations are also vulnerable to poaching, the cumulative effects of habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation, and climate changes (Wildlife Action Plan Team 2012). Therefore, a person shall not hunt or take any protected wildlife, or possess any part thereof, without first obtaining the appropriate license, permit or written authorization from the Nevada Department of Wildlife (Nevada Administrative Codes 503.090 and 503.093). The USDI Bureau of Land Management has recognized this lizard as a sensitive species since 1978 and is to manage public lands in a manner to avoid the necessity of higher federal protections (BLM Manual 6840 – Special Status Species). In Clark County’s Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan (MSHCP), the Gila monster is an Evaluation Species, meaning inadequate information exists to determine if mitigation from MSHCP implementation would demonstrably cover conservation actions necessary to ensure its persistence without additional protective intervention as provided under the federal Endangered Species Act. While the Gila monster is the only venomous lizard endemic to the United States, its behavioral disposition is somewhat docile and avoids confrontation. But it will readily defend itself if threatened. Most bites are considered illegitimate, not caused by Gila monster aggression, but resulting from human harassment or careless handling. -

Examination of the State-Dependency and Consequences of Foraging in a Low-Energy

Examination of the State-Dependency and Consequences of Foraging in a Low-Energy System, the Gila Monster, Heloderma Suspectum by Christian Wright A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2014 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Dale DeNardo, Chair Jon Harrison Kevin McGraw Brian Sullivan Blair Wolf ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2014 ABSTRACT Foraging has complex effects on whole-organism homeostasis, and there is considerable evidence that foraging behavior is influenced by both environmental factors (e.g., food availability, predation risk) and the physiological condition of an organism. The optimization of foraging behavior to balance costs and benefits is termed state-dependent foraging (SDF) while behavior that seeks to protect assets of fitness is termed the asset protection principle (APP). A majority of studies examining SDF have focused on the role that energy balance has on the foraging of organisms with high metabolism and high energy demands ("high-energy systems" such as endotherms). In contrast, limited work has examined whether species with low energy use ("low-energy systems" such as vertebrate ectotherms) use an SDF strategy. Additionally, there is a paucity of evidence demonstrating how physiological and environmental factors other than energy balance influence foraging behavior (e.g. hydration state and free-standing water availability). Given these gaps in our understanding of SDF behavior and the APP, I examined the state-dependency and consequences of foraging in a low-energy system occupying a resource-limited environment - the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum, Cope 1869). In contrast to what has been observed in a wide variety of taxa, I found that Gila monsters do not use a SDF strategy to manage their energy reserves and that Gila monsters do not defend their energetic assets.