DANGEROUS DESERT DWELLERS? Gila Monsters and Rattlesnakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prolonged Poststrike Elevation in Tongue-Flicking Rate with Rapid Onset in Gila Monster, <Emphasis Type="Italic">

Journal of Chemical Ecology, Vol. 20. No. 11, 1994 PROLONGED POSTSTRIKE ELEVATION IN TONGUE- FLICKING RATE WITH RAPID ONSET IN GILA MONSTER, Heloderma suspectum: RELATION TO DIET AND FORAGING AND IMPLICATIONS FOR EVOLUTION OF CHEMOSENSORY SEARCHING WILLIAM E. COOPER, JR. I'* CHRISTOPHER S. DEPERNO I and JOHNNY ARNETT 2 ~Department of Biology Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne Fort Wayne. bldiana 46805 2Department of Herpetology Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 (Received May 6, 1994; accepted June 27, 1994) Abstract--Experimental tests showed that poststrike elevation in tongue-flick- ing rate (PETF) and strike-induced chemosensory searching (SICS) in the gila monster last longer than reported for any other lizard. Based on analysis of numbers of tongue-flicks emitted in 5-rain intervals, significant PETF was detected in all intervals up to and including minutes 41~-5. Using 10-rain intervals, PETF lasted though minutes 46-55. Two of eight individuals con- tinued tongue-flicking throughout the 60 rain after biting prey, whereas all individuals ceased tongue-flicking in a control condition after minute 35. The apparent presence of PETF lasting at least an hour in some individuals sug- gests that there may be important individual differences in duration of PETF. PETF and/or SICS are present in all families of autarchoglossan lizards stud- ied except Cordylidae, the only family lacking lingually mediated prey chem- ical discrimination. However, its duration is known to be greater than 2-rain only in Helodermatidae and Varanidae, the living representatives of Vara- noidea_ That prolonged PETF and S1CS are typical of snakes provides another character supporting a possible a varanoid ancestry for Serpentes. -

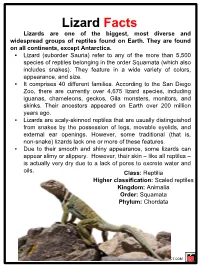

Lizard Facts Lizards Are One of the Biggest, Most Diverse and Widespread Groups of Reptiles Found on Earth

Lizard Facts Lizards are one of the biggest, most diverse and widespread groups of reptiles found on Earth. They are found on all continents, except Antarctica. ▪ Lizard (suborder Sauria) refer to any of the more than 5,500 species of reptiles belonging in the order Squamata (which also includes snakes). They feature in a wide variety of colors, appearance, and size. ▪ It comprises 40 different families. According to the San Diego Zoo, there are currently over 4,675 lizard species, including iguanas, chameleons, geckos, Gila monsters, monitors, and skinks. Their ancestors appeared on Earth over 200 million years ago. ▪ Lizards are scaly-skinned reptiles that are usually distinguished from snakes by the possession of legs, movable eyelids, and external ear openings. However, some traditional (that is, non-snake) lizards lack one or more of these features. ▪ Due to their smooth and shiny appearance, some lizards can appear slimy or slippery. However, their skin – like all reptiles – is actually very dry due to a lack of pores to excrete water and oils. Class: Reptilia Higher classification: Scaled reptiles Kingdom: Animalia Order: Squamata Phylum: Chordata KIDSKONNECT.COM Lizard Facts MOBILITY All lizards are capable of swimming, and a few are quite comfortable in aquatic environments. Many are also good climbers and fast sprinters. Some can even run on two legs, such as the Collared Lizard and the Spiny-Tailed Iguana. LIZARDS AND HUMANS Most lizard species are harmless to humans. Only the very largest lizard species pose any threat of death. The chief impact of lizards on humans is positive, as they are the main predators of pest species. -

Vernacular Name GILA MONSTER

1/6 Vernacular Name GILA MONSTER GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwestern U.S. and northwestern Mexico. HABITAT Succulent desert and dry sub-tropical scrubland, hillsides, rocky slopes, arroyos and canyon bottoms (mainly those with streams). CONSERVATION STATUS IUCN: Near Threatened (2016). Population Trend: Decreasing. Threats: - illegal exploitation by commercial and private collectors. - habitat destruction due to urbanization and agricultural development. COOL FACTS Their common name “Gila” refers to the Gila River Basin in the southwest U.S. Their skin consists of many round, bony scales, a feature that was common among dinosaurs, but is unusual in today's reptiles. The Gila monster and the Mexican beaded lizard are the only lizards known to be venomous. Both live in North America. Gila monsters are the largest lizards native to the U.S. Gila monsters may bite and not let go, continuing to chew and, thereby, inject more venom into their victims. Venom is released from the venom glands (modified salivary glands) into the lower jaws and travels up grooves on the outside of the teeth and into the victims as the Gila monsters bite. The lizards lack the musculature to forcibly inject the venom; instead the venom is propelled from the gland to the tooth by chewing. Capillary action brings the venom out of the tooth and into the victim. Gila monsters have been observed to flip over while biting the victim, presumably to aid the flow of the venom into the wound. Bites are painful, but rarely fatal to humans in good health. While the bites can overpower predators and prey, they are rarely fatal to humans in good health although humans may suffer pain, edema, bleeding, nausea and vomiting. -

Patterns in Protein Components Present in Rattlesnake Venom: a Meta-Analysis

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 1 September 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202009.0012.v1 Article Patterns in Protein Components Present in Rattlesnake Venom: A Meta-Analysis Anant Deshwal1*, Phuc Phan2*, Ragupathy Kannan3, Suresh Kumar Thallapuranam2,# 1 Division of Biology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville 2 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville 3 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas, Fort Smith, Arkansas # Correspondence: [email protected] * These authors contributed equally to this work Abstract: The specificity and potency of venom components gives them a unique advantage in development of various pharmaceutical drugs. Though venom is a cocktail of proteins rarely is the synergy and association between various venom components studied. Understanding the relationship between various components is critical in medical research. Using meta-analysis, we found underlying patterns and associations in the appearance of the toxin families. For Crotalus, Dis has the most associations with the following toxins: PDE; BPP; CRL; CRiSP; LAAO; SVMP P-I & LAAO; SVMP P-III and LAAO. In Sistrurus venom CTL and NGF had most associations. These associations can be used to predict presence of proteins in novel venom and to understand synergies between venom components for enhanced bioactivity. Using this approach, the need to revisit classification of proteins as major components or minor components is highlighted. The revised classification of venom components needs to be based on ubiquity, bioactivity, number of associations and synergies. The revised classification will help in increased research on venom components such as NGF which have high medical importance. Keywords: Rattlesnake; Crotalus; Sistrurus; Venom; Toxin; Association Key Contribution: This article explores the patterns of appearance of venom components of two rattlesnake genera: Crotalus and Sistrurus to determine the associations between toxin families. -

Inventory of Amphibians and Reptiles at Death Valley National Park

Inventory of Amphibians and Reptiles at Death Valley National Park Final Report Permit # DEVA-2003-SCI-0010 (amphibians) and DEVA-2002-SCI-0010 (reptiles) Accession # DEVA- 2493 (amphibians) and DEVA-2453 (reptiles) Trevor B. Persons and Erika M. Nowak Common Chuckwalla in Greenwater Canyon, Death Valley National Park (TBP photo). USGS Southwest Biological Science Center Colorado Plateau Research Station Box 5614, Northern Arizona University Flagstaff, Arizona 86011 May 2006 Death Valley Amphibians and Reptiles_____________________________________________________ ABSTRACT As part of the National Park Service Inventory and Monitoring Program in the Mojave Network, we conducted an inventory of amphibians and reptiles at Death Valley National Park in 2002- 2004. Objectives for this inventory were to: 1) Inventory and document the occurrence of reptile and amphibian species occurring at DEVA, primarily within priority sampling areas, with the goal of documenting at least 90% of the species present; 2) document (through collection or museum specimen and literature review) one voucher specimen for each species identified; 3) provide a GIS-referenced list of sensitive species that are federally or state listed, rare, or worthy of special consideration that occur within priority sampling locations; 4) describe park-wide distribution of federally- or state-listed, rare, or special concern species; 5) enter all species data into the National Park Service NPSpecies database; and 6) provide all deliverables as outlined in the Mojave Network Biological Inventory Study Plan. Methods included daytime and nighttime visual encounter surveys, road driving, and pitfall trapping. Survey effort was concentrated in predetermined priority sampling areas, as well as in areas with a high potential for detecting undocumented species. -

Lizards & Snakes Alive!

Media Inquiries: Aubrey Gaby; Department of Communications March 2010 212-496-3409; [email protected] www.amnh.org LIZARDS & SNAKES: ALIVE! BACK ON VIEW AT THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY MARCH 6–SEPTEMBER 6, 2010 RETURNING EXHIBITION SHOWCASES MORE THAN 60 LIVE LIZARDS AND SNAKES FROM AROUND THE WORLD The real monsters, dragons, and basilisks are back! More than 60 live lizards and snakes from five continents reside in exquisitely prepared habitats. In addition to the live animals, the exhibit uses interactive stations, significant fossils, and an award-winning video to acquaint visitors with the world of the Squamata, the group that includes lizards and snakes. Visitors can learn about chameleons’ ballistic tongues, how basilisks escape from predators by running across water, amazing camouflage of Madagascar geckos, the 3-D thermal vision of rattlesnakes and boas, spitting cobra fangs, blood-squirting Horned Lizards, flying snakes and lizards, and other gravity-defying squamates. Approximately 8,000 species of lizards and snakes have been recognized and new species continue to be discovered. In Lizards & Snakes: Alive! visitors will see 26 species, including crowd favorites such as the Gila Monster, Eastern Water Dragon, Green Basilisk, Veiled Chameleon, Blue-tongued Skink, Rhinoceros Iguana, Eastern Green Mamba, and a fourteen-foot Burmese Python. The Water Monitor habitat is equipped with a Web camera enabling virtual visitors around the globe to observe the daily behavior of one of the largest living species of lizard on Earth. One case in the exhibition includes four species of geckos: Madagascan Giant Day Geckos, Common Leaf- tailed geckos, Lined Leaf-tailed Geckos, and Henkel’s Leaf-tailed Geckos. -

Venomous Reptiles of Nevada

Venomous Reptiles of Nevada Figure 1 The buzz from a rattlesnake can signal a heart stopping adventure to even the most experienced outdoor enthusiast. Figure 2 Authors M. L. Robinson, Area Specialist, Water/Environmental Horticulture, University of Nevada Cooperative Extension Polly M. Conrad, Wildlife Diversity Biologist—Reptiles, Nevada Department of Wildlife Maria M. Ryan, Area Specialist, Natural Resources, University of Nevada Cooperative Extension Updated from G. Mitchell, M.L. Robinson, D.B. Hardenbrook and E.L. Sellars. 1998. What’s the Buzz About Nevada’s Venomous Reptiles? University of Nevada Cooperative Extension—Nevada Department of Wildlife Partnership Publication. FS-98-35. SP 07-07 (Replaces FS-98-35) NEVADA’S REPTILES Approximately 52 species of snakes and lizards share the Nevada landscape with us. Of these, only 12 are considered venomous. Only 6 can be dangerous to people and pets. Encountering them is uncommon because of their body camouflage and secretive nature, which are their first defenses in evading predators. Consider yourself fortunate if you do see one! As with all wildlife, treat venomous reptiles with respect. Reptiles are ectothermic, meaning their body temperature increases or decreases in response to the surrounding environment. They are most active in the spring, summer and early fall when it’s comfortable, short sleeve weather for us. Reptiles usually hibernate, or brumate, in winter in response to colder temperatures. During high summer temperatures in the Mojave Desert, reptiles may spend time underground in order to maintain vital body temperatures. In most cases*, collecting Nevada’s native reptiles is not allowed without the appropriate permit, which is issued by the Nevada Department of Wildlife. -

BMGR-W Small Mammal, Reptile, Amphibian Brochure

CONSERVING THE LANDSCAPE For additional information regarding REPTILES, AMPHIBIANS, & AND THE DOD MISSION reptiles, amphibians, and small As the manager and primary user of the SMALL MAMMALS OF THE 700k acre Barry M. Goldwater Range mammals or for general inquires West (BMGR-W), the U.S. Marine Corps regarding natural resources BMGR-W (USMC) is responsible for maintaining management on the BMGR-W, please MARINE CORPS AIR STATION YUMA the ecological integrity of the range, while simultaneously providing a realis- contact the Range Management tic training environment for our nation’s Department: warfighters. Additionally, the Military Lands Withdrawal Act of 1999 and the Sikes Act mandates that the USMC de- velop and adhere to an Integrated Natu- ral Resources Management Plan (INRMP) which “includes provisions for proper management and protection of the natural and cultural resources of the range, and for sustainable use by the public of such resources to the extent consistent with military purposes.” The INRMP for the BMGR-W requires that baseline surveys for small mammals, MCAS Yuma/Range Management Dept. reptiles, and amphibians be established so that natural resource managers may P.O. Box 99134/BLDG. 151 determine how best to allocate efforts Yuma, AZ 85369-9134 to protect these resources. The infor- mation presented in this brochure is a product of that objective and is being Phone: 928-269-3402 provided to increase public awareness and enhance the visitor experience. Small Mammals Continued: Amphibians : Reptiles (Snakes): □ Rock Squirrel, -

Distribution of Crotalus Scutulatus (Kennicott, 1861) in Tamaulipas, Mexico and Notes on Earliest Seasonal Parturition

Herpetology Notes, volume 13: 1087-1093 (2020) (published online on 28 December 2020) Distribution of Crotalus scutulatus (Kennicott, 1861) in Tamaulipas, Mexico and notes on earliest seasonal parturition William L. Farr1 and Sergio A. Terán-Juárez2,* Abstract. In Tamaulipas, Mexico, Crotalus scutulatus is known from only two specimens collected from the same locality almost a century ago. Both were catalogued as Crotalus atrox at that time and one of the two remained so as recently as 2003, while the other has been transferred between three collections and re-identified in the intervening years. Our aim was to locate additional records (museum, literature, and field) and establish the distributional limits of C. scutulatus in Tamaulipas. Fieldwork yielded additional records, which are mapped, and the habitat is described. Among the field records are neonates that indicate the earliest reported parturition dates for the species. To the best of our knowledge this is the first review that specifically addresses the occurrence of C. scutulatus in Tamaulipas. Keywords. distribution, habitat, vegetation zones, parturition Introduction the Northern Mohave Rattlesnake, C. s. scutulatus (Kennicott, 1861) and the Huamantla Rattlesnake, The Mohave Rattlesnake, Crotalus scutulatus C. s. salvini Günther, 1895. Crotalus s. scutulatus (Kennicott, 1861), inhabits the deserts of the south- is distributed from the Mojave Desert in southern western United States and the interior central plateau of California, the southern tip of Nevada, extreme south- Mexico. Recent studies have examined cryptic genetic western Utah, south-eastward through much of Arizona, diversity and geographic variation in morphology, northern Sonora, extreme southern New Mexico, the providing evidence that various populations of the Big Bend region of Texas, and southward across the species have undergone several episodes of isolation and Mexican Plateau, including southwest Tamaulipas, secondary contact that produced four genetic lineages: into Guanajuato. -

Enter the Dragon: the Dynamic and Multifunctional Evolution of Anguimorpha Lizard Venoms

Article Enter the Dragon: The Dynamic and Multifunctional Evolution of Anguimorpha Lizard Venoms Ivan Koludarov 1, Timothy NW Jackson 1,2, Bianca op den Brouw 1, James Dobson 1, Daniel Dashevsky 1, Kevin Arbuckle 3, Christofer J. Clemente 4, Edward J. Stockdale 5, Chip Cochran 6, Jordan Debono 1, Carson Stephens 7, Nadya Panagides 1, Bin Li 8, Mary‐Louise Roy Manchadi 9, Aude Violette 10, Rudy Fourmy 10, Iwan Hendrikx 1, Amanda Nouwens 11, Judith Clements 7, Paolo Martelli 12, Hang Fai Kwok 8 and Bryan G. Fry 1,* 1 Venom Evolution Lab, School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St. Lucia QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] (I.K.); [email protected] (T.N.W.J.); [email protected] (B.o.d.B.); [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (N.P.); [email protected] (I.H.) 2 Australian Venom Research Unit, School of Biomedical Sciences, Level 2 Medical Building, University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia 3 Department of Biosciences, College of Science, Swansea University, Swansea SA2 8PP, UK; [email protected] 4 University of the Sunshine Coast, School of Science and Engineering, Sippy Downs, Queensland 4558, Australia; [email protected] 5 Gradient Scientific and Technical Diving, Rye, Victoria 3941, Australia; [email protected] (E.J.S.) 6 Department of Earth and Biological Sciences, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA 92350, USA; [email protected] 7 School of Biomedical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane QLD 4001, Australia; [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (J.C.) 8 Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, Avenida da Universidade, Taipa, Macau; [email protected] (B. -

AMPHIBIANS and REPTILES of ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL MONUMENT Compiled by the Interpretive Staff with Technical Assistance from Dr

AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES OF ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL MONUMENT Compiled by the Interpretive Staff With Technical Assistance From Dr. J . C. McCoy, Carnegie Museum, Pittsburg, Pa. and Dr. Robert C. Stebbins, University of California, Berkeley Comm:m Names Scientific Names Amphibians Class Amphibia Frogs ~ Toads Order Sa.;J.ienta Toads Family Bufonidae Colorado River toad Bufo alvaris (s) Great plains toad nuro co~tus (s) Red- spotted toad Biil'O puncatus (s) Sonora green toad Buf'O retiformis Spadefoot Toads Family Pelobatidae Couch's spadefoot Scaphiopus couchi (8) Reptiles Class Reptilia Turtles Order Testudinata Mud Turtles and Their Allies Family Chelydridae Sonora mud turtle Kinosternon sonorien8e (s) Land Tortoises and Their Allies Family Testudinjdae - -.;.;.;.;;;.;;;;;..--- Desert tortoise Gopherus agassizi Lizards and Snakes Order Squamata Lizards Suborder Sauria Geckos Family Gekkonidae Desert banded gecko Coleoqyx ! . variegatus (s) Iguanids Family Iguanidae Arizona zebra- tailed lizard Callisaurus draconoides ventralis (s) Western collard lizard Crotaphytus collaris bailer) ( s) Long-nosed leopard lizard Crotaphytus ! . wislizeni (s Desert iguana ~saurus d. dorsalis (s) Southern desert horned lizard osoma p!atyrhinos calidiarum Regal horned lizard Phrynosoma solara ( s) Arizona chuckwalla Sauromalus obesus tumidus (s) Desert spi~ lizard SceloEorus m. magister (s) Colorado River tree lizard Urosaurus ornatus symmetricus (s) Desert side-blotched lizard ~ stansburiana stejnegeri (s) Teids Family Teidae Red-backed whiptail Cnemidophorus burti xanthonot us ~) Southern whiptail Cnemidophorus tigris gracilis (6) Venomous Lizards Family Heloderrr~tidae Reticula.te Gila m:mster Heloderma ! .. suspectum (6) Snakes Suborder Serpentes Worm Snakes Family Leptotyphlopidae Southwestern blind snake Leptottphlops h. humilis (s) Boas Family Boidae Desert rosy boa Lichanura trivirgata gracia (s) Colubrids Family Colubridae Arizona glossy snake Arizona elegans noctivaga c. -

Year of the Lizard News No

Year of the Lizard News No. 4 July 2012 V V V V V V V V V V www.YearoftheLizard.org Lizards Across the Land: Federal Agencies’ Role From Alaska to Hawaii to Florida, hundreds of millions of acres of our public lands are held in trust by federal land management agencies. Many of these lands support rich and diverse populations of lizards. The following collection of articles provides a sample of the outstanding scholarly and practical work being conducted on our federal public lands. Biologists at these and other federal agencies are hard at work to answer many important questions regarding A Copper-striped Blue-tailed Skink (Emoia impar) the science of lizard conservation and management and to photographed in Samoa during a USGS field survey. identify and conserve priority habitats for lizards and other Photo: Chris Brown, USGS. native wildlife. “No other landscape in these United States has —Terry Riley, National Park Service, National PARC been more impacted by extinction events and species Federal Agencies Coordinator invasions in historic times than the Hawaiian Islands, with as yet unknown long-term cascading consequences USGS Reveals “Cryptic Extinction” of Pacific to the ecosystem,” said U.S. Geological Survey director Lizard Marcia McNutt. “Today, we close the book on one more animal that is unlikely to ever be re-established in this A species of lizard is now extinct from the Hawaiian fragile island home.” Islands, making it the latest native vertebrate species to “This skink was once common throughout the become extirpated from this tropical archipelago. Hawaiian Islands, and in fact the species can still be The Copper-striped Blue-tailed Skink (Emoia impar) — found on many other island groups in the tropical a sleek lizard with smooth, polished scales and a long, sky- blue tail — was last confirmed in the Na’Pali coast of Kauai continued on p.