LAND, INDIGENISATION and EMPOWERMENT Narratives That Made a Difference in Zimbabwe’S 2013 Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enreporting on Zimbabwe's 2018 Elections

Reporting on Zimbabwe’s 2018 elections A POST-ELECTION ANALYSIS Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1 PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS 8 2.0 MEDIA MONITORING OF THE NEWS AGENDA 8 3.0 MONITORING POLITICAL PLURALISM 13 4.0 GENDER REPRESENTATION DURING THE 2018 ELECTIONS 18 5.0 MEDIA CONDUCT IN ELECTION PROGRAMMING - BROADCAST MEDIA 24 6.0 MEDIA’S CONDUCT IN ELECTION REPORTING 28 7.0 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 34 ANNEX 1: HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS REPORTED IN THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA 35 ANNEX 2: LIST OF ACRONYMS 37 REPORTING ON ZIMBABWE’S 2018 ELECTIONS - A POST-ELECTION ANALYSIS i Acknowledgements International Media Support and the Media Alliance of Zimbabwe This publication has been produced with the assistance of the are conducting the programme “Support to media on governance European Union and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. and electoral matters in Zimbabwe”. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Media Monitors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views The programme is funded by the European Union and the of the European Union or the Norwegian Ministry of Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Foreign Affairs. International Media Support (IMS) is a non-profit organisation working with media in countries affected by armed conflict, human insecurity and political transition. ii REPORTING ON ZIMBABWE’S 2018 ELECTIONS - A POST-ELECTION ANALYSIS Executive Summary Zimbabwe’s 2018 harmonised national elections presented a irregularities, they struggled to clearly articulate the implications unique opportunity for the media and their audiences alike. In of the irregularities they reported and the allegations of previous election periods, the local media received severe criticism maladministration levelled against the country’s election for their excessively partisan positions, which had been characterized management body, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC). -

A Comparative Study of Zimbabwe and South Africa

FACEBOOK, YOUTH AND POLITICAL ACTION: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ZIMBABWE AND SOUTH AFRICA A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MEDIA STUDIES, RHODES UNIVERSITY by Admire Mare September 2015 ABSTRACT This comparative multi-sited study examines how, why and when politically engaged youths in distinctive national and social movement contexts use Facebook to facilitate political activism. As part of the research objectives, this study is concerned with investigating how and why youth activists in Zimbabwe and South Africa use the popular corporate social network site for political purposes. The study explores the discursive interactions and micro- politics of participation which plays out on selected Facebook groups and pages. It also examines the extent to which the selected Facebook pages and groups can be considered as alternative spaces for political activism. It also documents and analyses the various kinds of political discourses (described here as digital hidden transcripts) which are circulated by Zimbabwean and South African youth activists on Facebook fan pages and groups. Methodologically, this study adopts a predominantly qualitative research design although it also draws on quantitative data in terms of levels of interaction on Facebook groups and pages. Consequently, this study engages in data triangulation which allows me to make sense of how and why politically engaged youths from a range of six social movements in Zimbabwe and South Africa use Facebook for political action. In terms of data collection techniques, the study deploys social media ethnography (online participant observation), qualitative content analysis and in-depth interviews. -

1 Daily Media Monitoring Report Issue 4: 3 June 2018 Table of Contents

Daily Media Monitoring Report Issue 4: 3 June 2018 Table of Contents 1.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Key Events .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Media Monitored ................................................................................................................. 2 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 Did the media represent political parties in a fair and balanced manner? .......................... 3 2.1 Space and time dedicated to political parties in private and public media ...................... 3 2.2 Space and time dedicated to political actors in private and public media ....................... 4 2.3 Tone of coverage for political parties .............................................................................. 5 2.4 Gender representation in election programmes ............................................................. 7 2.5 Youth representation in election programmes ................................................................ 8 2.6 Time dedicated to political players in the different programme types in broadcast media .............................................................................................................................................. 9 3.0 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................... -

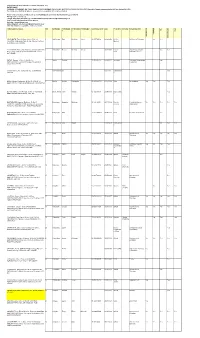

Updated Sanctions List

Compiled List of 349 Individuals on various 'Sanctions' lists. DATA FORMAT: SURNAME, FORENAMES, NATIONAL IDENTIFICATION NUMBER; DATE OF BIRTH;POSITION; ORGANISATION; LISTS (Australia, Canada, European Union EU, New Zealand NZ, USA. The List includes individuals who are deceased and occupational data may be outdated. Please send corrections, additions, etc to: [email protected] and to the implementing governments EU: http://eur-lex.europa.eu Canada: http://www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/trade/zimbabwe-en.asp [email protected] New Zealand: http://www.immigration.govt.nz Australia: [email protected] United Kingdom: [email protected] USA: http://www.treas.gov/offices/enforcement/ofac D CONSOLIDATED DATA REF SURNAME FORENAME FORENAME FORENAME 3 NATIONAL ID NO DoB POSITION SPOUSE ORGANISATION EU 1 2 USA CANADA AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAN ABU BASUTU, Titus Mehliswa Johna. ID No: 63- 1 Abu Basutu Titus Mehliswa Johna 63-375701F28 02/06/1956 Air Vice- Air Force of Zimbabwe Yes Yes 375701F28. DOB:02/06/1956. Air Vice-Marshal; Air Force Marshal of Zimbabwe LIST: CAN/EU/ AL SHANFARI, Thamer Bin Said Ahmed. DOB:30/01/1968. 2 Al Shanfari Thamer Bin Said Ahmed 30/01/1968 Former Oryx Group and Oryx Yes Yes Former Chair; Oryx Group and Oryx Natural Resources Chair Natural Resources LIST: EU/NZ/ BARWE, Reuben . ID No: 42- 091874L42. 3 Barwe Reuben 42- 091874L42 19/03/1953 Journalist Zimbabwe Broadcasting Yes DOB:19/03/1953. Journalist; Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation Corporation LIST: EU/ BEN-MENASHE, Ari . DOB:circa 1951. Businessman; 4 Ben-Menashe Ari circa 1951 Businessma Yes LIST: NZ/ n BIMHA, Michael Chakanaka . -

The Mortal Remains: Succession and the Zanu Pf Body Politic

THE MORTAL REMAINS: SUCCESSION AND THE ZANU PF BODY POLITIC Report produced for the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum by the Research and Advocacy Unit [RAU] 14th July, 2014 1 CONTENTS Page No. Foreword 3 Succession and the Constitution 5 The New Constitution 5 The genealogy of the provisions 6 The presently effective law 7 Problems with the provisions 8 The ZANU PF Party Constitution 10 The Structure of ZANU PF 10 Elected Bodies 10 Administrative and Coordinating Bodies 13 Consultative For a 16 ZANU PF Succession Process in Practice 23 The Fault Lines 23 The Military Factor 24 Early Manoeuvring 25 The Tsholotsho Saga 26 The Dissolution of the DCCs 29 The Power of the Politburo 29 The Powers of the President 30 The Congress of 2009 32 The Provincial Executive Committee Elections of 2013 34 Conclusions 45 Annexures Annexure A: Provincial Co-ordinating Committee 47 Annexure B : History of the ZANU PF Presidium 51 2 Foreword* The somewhat provocative title of this report conceals an extremely serious issue with Zimbabwean politics. The theme of succession, both of the State Presidency and the leadership of ZANU PF, increasingly bedevils all matters relating to the political stability of Zimbabwe and any form of transition to democracy. The constitutional issues related to the death (or infirmity) of the President have been dealt with in several reports by the Research and Advocacy Unit (RAU). If ZANU PF is to select the nominee to replace Robert Mugabe, as the state constitution presently requires, several problems need to be considered. The ZANU PF nominee ought to be selected in terms of the ZANU PF constitution. -

New Broadcasters Likely to Tighten State Media's Stranglehold

Defending free expression and your right to know Media Monitoring Project Zimbabwe Monday November 7th – Sunday November 13th 2011 Weekly Media Review 2011-45 New broadcasters likely to tighten State media’s stranglehold COMMENT THE inclusion of Talk Radio – a project of the country’s state-owned publishing house, Zimpapers, whose products still dominate Zimbabwe’s print media landscape – among the four shortlisted applicants for national radio licences has renewed the public’s cynicism over the authorities’ political will to diversify Zimbabwe’s airwaves. The other applicants comprise Hotmedia (Pvt) Ltd trading as Kiss FM, A.B Communications, owned by former ZBC news anchor, Supa Mandiwanzira, and Voice of the People (VoP), which is currently broadcasting from abroad. While the Broadcasting Services Act (BSA) as amended in 2007 allows for cross-ownership of the media, the short-listing of Talk Radio raises ethical issues and contradicts the spirit of the Global Political Agreement (GPA), which, according to Article XIX of the agreement, is: “Desirous of ensuring the opening up of the airwaves and ensuring the operation of as many media houses as possible.” Licensing Talk Radio, which is “tipped to clinch one of the two licences up for grabs” (NewsDay 20/10), would not only deprive prospective private broadcasters of the chance to operate, but would expand and entrench the biased state media’s monopoly of the broadcasting sector, already the preserve of the country’s sole broadcaster, ZBC. The Broadcasting Authority of Zimbabwe (BAZ), responsible for awarding operating licences to prospective broadcasters, is itself a disputed body that parties to the GPA had agreed should be reconstituted due to the irregular and partisan appointment of its members by the Minister of Information a year ago. -

A Week of Protests - from Beitbridge to The

A week of protests - From Beitbridge to the shutdown How was the conflict reported? 1 Contents 1.Background 2. The Beitbridge protest 2.1 The events 2.2 Who were the protesters? 2.3 Why did they protest? 3. The Monday Protests 4. The Shutdown 4.1 Who was behind it? 4.2 The ruling party's response 4.3 What happened on the 6th? 4.4 SADC and the protests 5. The official narrative 5.1 The Zimbabwe Republic Police 5.2 POTRAZ 5.3 The Broadcasting Authority of Zimbabwe 6. Conclusion 2 1. Background The events in the seven days beginning 1 July 2016, starting with the protests in the border town of Beitbridge have been momentous in the history of Zimbabwe. The reportage of these events show that there is no one story on Zimbabwe, but several stories, told from various perspectives, and the citizen is found in the middle, battling to decipher the truth. These narratives presented by the traditional media houses, social and alternative (mainly online) media as well as official statements make truth a tenuous concept, as facts are sometimes lost in a sometimes-tinted view of the world. Questions that arise include, after all the stories have been told, does the world have a clear idea of the current crisis in Zimbabwe, its root causes, possible impact, key players and what the possible resolution will look like? Do we have a clear idea of what the Zimbabwean story is? What is the role of the media in all this? Professional journalism is called upon to be truthful, fair, accurate and balanced, playing a critical role in informing the public and promoting public accountability, two critical preconditions for democracy. -

Zimbabwe's Liberation Struggle Era Conflicts and the Pitfalls Of

TITLE: Zimbabwe’s Liberation Struggle Era Conflicts and the Pitfalls of Reconciliation after Independence: A Case Study of Bikita District 1976-2013. By Dorothy Goredema A Thesis submitted to the Midlands State University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. Faculty of Arts Midlands State University 2015 i Declaration I Dorothy Goredema, hereby declare that this thesis for the Doctor of Philosophy in History at the Midlands State University, hereby submitted by me, has not been previously submitted for a degree at this or any other institution, and that this is my work in design and execution, and all reference materials contained herein have been duly acknowledged. ………………………………………… …………………………………….. Signature Date I hereby certify that the above statement is correct. Main Supervisor, Prof. N.Bhebe………………. …. ………………………… Signature Date Co-Supervisor, Dr.T.M Mashingaidze…………….. …………………………… Signature Date i Acknowledgements I owe a special debt of gratitude to my main supervisor, Professor Ngwabi Bhebe, and Dr. T.M Mashingaidze. Firstly, Professor Bhebe, I will be forever indebted to you. Despite your busy schedule as Vice-Chancellor of a university, you would always make time for me as a student and for my work. You took an interest in my topic and gave direction to many of my disjointed ideas that marked the genesis of the study. You continuously assessed my work, giving me feedback on time and went an extra mile to facilitate co-supervisors and funds that supported my work. I will forever be indebted to your efficiency, wise counsel and critical mind. Thank you Professor for your mentorship and intellectual support. -

The Dynamics of Factionalism in ZANUPF: 1980–2017

Midlands State University FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES THE DYNAMICS OF FACTIONALISM IN ZANU PF: 1980 – 2017 BY TAPIWA PATSON SISIMAYI (R0538644) DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE MIDLANDS STATE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR A MASTER OF ARTS DEGREE IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES ZVISHAVANE 2019 RELEASE FORM NAME OF AUTHOR: SISIMAYI TAPIWA PATSON TITLE OF PROJECT: THE DYNAMICS AND DIMENSIONS OF FACTIONALISM IN ZANU PF: 1980 – 2017 PROGRAMME: MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES YEAR THIS MASTERS DEGREE WAS GRANTED: 2019 Consent is hereby granted to the Midlands State University to produce copies of this dissertation and to lend or sell such copies for scholarly or scientific research purpose only. The author reserves the publication rights and neither the dissertation nor extensive extracts from it may be published or otherwise reproduced without the author’s written permission. SIGNED: …………………………………………………………. EMAIL: [email protected] DATE: MAY 2019 ii DECLARATION Student number: R0538644 I, Sisimayi Tapiwa, Patson author of this dissertation, do hereby declare that the work presented in this document entitled: THE DYNAMICS AND DIMENSIONS OF FACTIONALISM IN ZANU PF: 1980 - 2017, is an outcome of my independent and personal research, all sources employed have been properly acknowledged both in the dissertation and on the reference list. I also certify that the work in this dissertation has not been submitted in whole or in part for any other degree in this University or in any institute of higher learning. ……………………………………………………… …….…. /………. /2019 Tapiwa Patson Sisimayi Date SUPERVISOR: Doctor Douglas Munemo iii DEDICATION To my son Tapiwa Jr. -

Newsletter Zimbabwe Issue 9 • February - May 2014

United Nations in Zimbabwe UnitedÊNationsÊ Newsletter Zimbabwe Issue 9 • February - May 2014 www.zw.one.un.org SPECIAL FOCUS Gender Equality IN THIS ISSUE The ninth edition of the United Nations in Zimbabwe newsletter is dedicated to PAGE 1 UN engagement in promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment Advancing Women’s Rights Through initiatives in Zimbabwe. This newsletter also highlights issues related to Constitutional Provisions health, skills, and human trafficking. Finally, this newsletter covers updates PAGE 3 on the development of the new Zimbabwe United Nations Development A Joint UN UnitedÊNationsÊ Programme to Assistance Framework (ZUNDAF) for 2016-2020, the UN’s partnership with Advance Women’s the Harare International Festival of Arts, and the Zimbabwe International Empowerment Trade Fair. PAGE 4 Refurbishing Maternity Waiting FEATURE ARTICLE: Homes to Enhance Zimbabwe Maternal Health Services Advancing Women’s Rights Through PAGE 5 “Not Yet Uhuru” in Realising Maternal Constitutional Provisions and Child Health Rights The new Constitution adopted Constitution provides the bedrock A special through a popular referendum in upon which systems and policies measure to PAGE 6 Promoting Gender 2013 was a major milestone in the can be built to enhance women’s increase women’s Equality Through history of Zimbabwe. Zimbabweans equal participation in all sectors of representation in Harnessing the Power from all walks of life participated society. Parliament, and of Radio in translating their individual and To mark this breakthrough for a provision for collective aspirations into a new achieving gender PAGE 7 women in the new Constitution, Empowering Women Supreme Law of the land. the national commemoration of balance in all and Youth With New public entities and Skills Women, both as individuals and the 2014 International Women’s as organized groups, actively Day was held under the theme, commissions are PAGE 8 participated in the constitution- “Celebrating Women’s Gains now part of the New Law in Place new Constitution. -

Zimbabwe's Power Sharing Government and the Politics Of

Creating African Futures in an Era of Global Transformations: Challenges and Prospects Créer l’Afrique de demain dans un contexte de transformations mondialisées : enjeux et perspectives Criar Futuros Africanos numa Era de Transformações Globais: Desafios e Perspetivas بعث أفريقيا الغد في سياق التحوﻻت المعولمة : رهانات و آفاق Toward more democratic futures: making governance work for all Africans Zimbabwe’s Power Sharing Government and the Politics of Economic Indigenisation, 2009 to 2013 Musiwaro Ndakaripa Toward more democratic futures: making governance work for all Africans Zimbabwe’s Power Sharing Government and the Politics of Economic Indigenisation, 2009 to 2013 Abstract Using the economic indigenisation policy this study examines the problems caused by Zimbabwe‟s power sharing government (PG) to democratic governance between 2009 and 2013. The power sharing government experienced policy gridlock in implementing the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act of 2007 due to disagreements among the three governing political parties which were strategising to gain political credibility and mobilising electoral support to ensure political survival in the long term. The Indigenisation Act intends to give indigenous black Zimbabweans at least fifty one per cent (51%) shareholding in all sectors of the economy. The Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) posited that economic indigenisation rectifies colonial imbalances by giving black Zimbabweans more control and ownership of the nation‟s natural resources and wealth. The two Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) political parties in the power sharing government asserted that while economic indigenisation is a noble programme, it needs revision because it discouraged Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Moreover, the two MDC parties claimed that economic indigenisation is a recipe for ZANU-PF elite enrichment, clientelism, cronyism, corruption and political patronage. -

Parliamentary Performance and Gender

Parliamentary Performance and Gender Rumbidzai Dube, Senior Researcher November 2013 1 | Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A gendered analysis of the last year of the Seventh Parliament of Zimbabwe indicates that the general facilitatory and inhibitory dynamics affecting ordinary women’s participation in politics and decision-making are the same dynamics that affect women in Parliament. Women who take an active role in governance and political life are confronted by inhibiting factors including patriarchy and the violent nature of the political terrain. Women who manage to attain political office would have clearly overcome enormous hurdles relative to their male counterparts. In Parliament, women still have to deal with the pervasive patriarchal attitudes that at times prevent them from fully participating. Even the President has proven himself not to be immune to the prejudices of his gender with recent remarks that the limited number of women appointees in ministerial posts was due to the lack of educated and qualified women.1 With this broad context in mind, this report examines the performance of female parliamentarians versus their male counterparts, and is complementary to and draws from RAU’s earlier report on parliamentary attendance. Some key findings highlighted in this report: • Women were a significant minority in the Seventh Parliament 34/210 in the House of Assembly and 23/93 in the Senate; • As a group, female MPs attendance was more impressive than that of their male counterparts. All of them, except one, scored attendance rates