Parliamentary Performance and Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Sanctions Zimbabwe

Canadian Sanctions and Canadian charities operating in Zimbabwe: Be Very Careful! By Mark Blumberg (January 7, 2009) Canadian charities operating in Zimbabwe need to be extremely careful. It is not the place for a new and inexperienced charity to begin foreign operations. In fact, only Canadian charities with substantial experience in difficult international operations should even consider operating in Zimbabwe. It is one of the most difficult countries to carry out charitable operations by virtue of the very difficult political, security, human rights and economic situation and the resultant Canadian and international sanctions. This article will set out some information on the Zimbabwe Sanctions including the full text of the Act and Regulations governing the sanctions. It is not a bad idea when dealing with difficult legal issues to consult knowledgeable legal advisors. Summary On September 4, 2008, the Special Economic Measures (Zimbabwe) Regulations (SOR/2008-248) (the “Regulations”) came into force pursuant to subsections 4(1) to (3) of the Special Economic Measures Act. The Canadian sanctions against Zimbabwe are targeted sanctions dealing with weapons, technical support for weapons, assets of designated persons, and Zimbabwean aircraft landing in Canada. There is no humanitarian exception to these targeted sanctions. There are tremendous practical difficulties working in Zimbabwe and if a Canadian charity decides to continue operating in Zimbabwe it is important that the Canadian charity and its intermediaries (eg. Agents, contractor, partners) avoid providing any benefits, “directly or indirectly”, to a “designated person”. Canadian charities need to undertake rigorous due diligence and risk management to ensure that a “designated person” does not financially benefit from the program. -

Politics/International Relations

EUROPEAN UNION DELEGATION TO ZIMBABWE Weekly Press Review July 30-August 5, 2011 The views expressed in this review are those of the named media and not necessarily representative of the Delegation of the European Union to Zimbabwe. Politics/International Relations US prepared to work with Zanu PF -envoy NewsDay, August 3, 2011 United States Ambassador to Zimbabwe Charles Ray says Zanu PF has an important role to play in the country, adding that his country is not anti-Zanu PF and it recognises the many achievements that Zanu PF has had over the decades for the good of the Zimbabwean people. Presenting a paper on The Future of US-Zimbabwe Relations, Ray admitted relations between his country and Zimbabwe were like “a faltering joint venture”, which he blamed on both sides, but said he was optimistic these would normalise. He said his country believed all political parties had an important role to play in Zimbabwe’s future. No discussion of Zuma's role at SADC-Zulu NewsDay, August 4, 2011 South African President Jacob Zuma has scoffed at suggestions his role as facilitator to the Zimbabwe crisis ends this month when he assumes chairmanship of the Sadc Organ on Politics, Defence and Security, saying the issue was not on the agenda of the regional bloc’s Angola summit. SADC Heads of State and Government are expected to meet in Luanda, Angola, for the regional bloc’s 31st ordinary summit, where Zuma is expected to submit a report on Zimbabwe. Zanu PF hardliners are reportedly making underground manoeuvres to have Zuma removed as facilitator to the Zimbabwe political crisis, due to the South African leader’s unexpected hard line stance on President Robert Mugabe. -

Special Edition

Special Edition Issue #: 182 Tuesday, 14 May 2013 Calls for in- ‘May the force Women have 10 creased wom- be with you’ - years to make en’s representa- AN OPINION by the most of 60 tion gain mo- DELTA MILAYO seats mentum NDOU Calls for increased women’s rep- port Unit (WiPSU)’s launch of the ‘Vote for a Woman’ campaign held at the resentation gain momentum Other than being a litmus test for the Crowne Plaza hotel on 10 May 2013. determination and capacity of women to vote each other into Parliament, analysts Calls for increased women’s representa- say that this call for increased women WiPSU stated that the ‘Vote for a Wom- tion in political processes continue to representation will test the sincerity of an’ campaign was meant to accelerate gain momentum ahead of the upcoming the political parties themselves in honor- the number of women taking up positions watershed elections with women politi- ing the internal quota systems that some in Parliament and local government – a cians across the political divide singing of them created for aspiring female can- goal that appears to have won traction from the same political emancipation didates. hymn book. with female politicians from across the political divide. Buoyed by a Draft Constitution that has been largely hailed as a progressive docu- From Honorable Senator Tambudzani ment in terms of elevating the status of Mohadi of ZANU PF’s impassioned plea to Zimbabwean women, the goal of seeing fellow women whom she urged, more women in Parliament appears to be “Women leave your houses and go and the current preoccupation. -

Updated Sanctions List

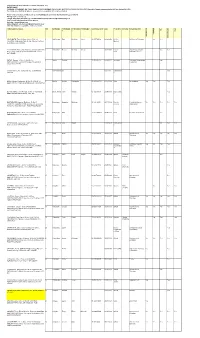

Compiled List of 349 Individuals on various 'Sanctions' lists. DATA FORMAT: SURNAME, FORENAMES, NATIONAL IDENTIFICATION NUMBER; DATE OF BIRTH;POSITION; ORGANISATION; LISTS (Australia, Canada, European Union EU, New Zealand NZ, USA. The List includes individuals who are deceased and occupational data may be outdated. Please send corrections, additions, etc to: [email protected] and to the implementing governments EU: http://eur-lex.europa.eu Canada: http://www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/trade/zimbabwe-en.asp [email protected] New Zealand: http://www.immigration.govt.nz Australia: [email protected] United Kingdom: [email protected] USA: http://www.treas.gov/offices/enforcement/ofac D CONSOLIDATED DATA REF SURNAME FORENAME FORENAME FORENAME 3 NATIONAL ID NO DoB POSITION SPOUSE ORGANISATION EU 1 2 USA CANADA AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAN ABU BASUTU, Titus Mehliswa Johna. ID No: 63- 1 Abu Basutu Titus Mehliswa Johna 63-375701F28 02/06/1956 Air Vice- Air Force of Zimbabwe Yes Yes 375701F28. DOB:02/06/1956. Air Vice-Marshal; Air Force Marshal of Zimbabwe LIST: CAN/EU/ AL SHANFARI, Thamer Bin Said Ahmed. DOB:30/01/1968. 2 Al Shanfari Thamer Bin Said Ahmed 30/01/1968 Former Oryx Group and Oryx Yes Yes Former Chair; Oryx Group and Oryx Natural Resources Chair Natural Resources LIST: EU/NZ/ BARWE, Reuben . ID No: 42- 091874L42. 3 Barwe Reuben 42- 091874L42 19/03/1953 Journalist Zimbabwe Broadcasting Yes DOB:19/03/1953. Journalist; Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation Corporation LIST: EU/ BEN-MENASHE, Ari . DOB:circa 1951. Businessman; 4 Ben-Menashe Ari circa 1951 Businessma Yes LIST: NZ/ n BIMHA, Michael Chakanaka . -

AC Vol 44 No 22

www.africa-confidential.com 7 November 2003 Vol 44 No 22 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL KENYA 2 ZIMBABWE The best money can buy No chance, Mr President Party officials and military commanders are ignoring President ‘Why hire a lawyer when you can buy a judge?’ is a well-worn joke Mugabe’s orders to surrender their farms that the younger reformers in Several government ministers and senior military officers accused of grabbing farms are refusing to hand President Kibaki’s government want to make redundant. But their efforts them back to the state, according to a new report on land reform ordered by President Robert Mugabe. are being undermined by veteran Information Minister Jonathan Moyo, Local Government Minister Ignatius Chombo and 13 other politicians and business people who ministers have secured several farms in violation of the government’s ‘one man, one farm’ rule, the report are using the purge of the judiciary says. Details of ministers’ and officers’ holdings are contained in a confidential annexe to the main report, to destroy their opponents. which has been discussed in cabinet. Mugabe asked former Secretary to the Government Charles Utete to investigate the findings of an GHANA 3earlier land audit by the Minister of State in Deputy President Joseph Msika’s office, Flora Buka. This had found major abuses of the land resettlement programme by senior officials (AC Vol 44 No 4). Buka’s Politics get crude audit reported that some of the worst violations of the land reform policy were perpetrated by Mugabe’s The row over crude oil supplies to closest political allies, such as Air Vice-Marshall Perence Shiri, Minister Moyo and Mugabe’s sister, the state-owned Volta River Sabina Mugabe. -

The Mortal Remains: Succession and the Zanu Pf Body Politic

THE MORTAL REMAINS: SUCCESSION AND THE ZANU PF BODY POLITIC Report produced for the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum by the Research and Advocacy Unit [RAU] 14th July, 2014 1 CONTENTS Page No. Foreword 3 Succession and the Constitution 5 The New Constitution 5 The genealogy of the provisions 6 The presently effective law 7 Problems with the provisions 8 The ZANU PF Party Constitution 10 The Structure of ZANU PF 10 Elected Bodies 10 Administrative and Coordinating Bodies 13 Consultative For a 16 ZANU PF Succession Process in Practice 23 The Fault Lines 23 The Military Factor 24 Early Manoeuvring 25 The Tsholotsho Saga 26 The Dissolution of the DCCs 29 The Power of the Politburo 29 The Powers of the President 30 The Congress of 2009 32 The Provincial Executive Committee Elections of 2013 34 Conclusions 45 Annexures Annexure A: Provincial Co-ordinating Committee 47 Annexure B : History of the ZANU PF Presidium 51 2 Foreword* The somewhat provocative title of this report conceals an extremely serious issue with Zimbabwean politics. The theme of succession, both of the State Presidency and the leadership of ZANU PF, increasingly bedevils all matters relating to the political stability of Zimbabwe and any form of transition to democracy. The constitutional issues related to the death (or infirmity) of the President have been dealt with in several reports by the Research and Advocacy Unit (RAU). If ZANU PF is to select the nominee to replace Robert Mugabe, as the state constitution presently requires, several problems need to be considered. The ZANU PF nominee ought to be selected in terms of the ZANU PF constitution. -

The Dynamics of Factionalism in ZANUPF: 1980–2017

Midlands State University FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES THE DYNAMICS OF FACTIONALISM IN ZANU PF: 1980 – 2017 BY TAPIWA PATSON SISIMAYI (R0538644) DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE MIDLANDS STATE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR A MASTER OF ARTS DEGREE IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES ZVISHAVANE 2019 RELEASE FORM NAME OF AUTHOR: SISIMAYI TAPIWA PATSON TITLE OF PROJECT: THE DYNAMICS AND DIMENSIONS OF FACTIONALISM IN ZANU PF: 1980 – 2017 PROGRAMME: MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES YEAR THIS MASTERS DEGREE WAS GRANTED: 2019 Consent is hereby granted to the Midlands State University to produce copies of this dissertation and to lend or sell such copies for scholarly or scientific research purpose only. The author reserves the publication rights and neither the dissertation nor extensive extracts from it may be published or otherwise reproduced without the author’s written permission. SIGNED: …………………………………………………………. EMAIL: [email protected] DATE: MAY 2019 ii DECLARATION Student number: R0538644 I, Sisimayi Tapiwa, Patson author of this dissertation, do hereby declare that the work presented in this document entitled: THE DYNAMICS AND DIMENSIONS OF FACTIONALISM IN ZANU PF: 1980 - 2017, is an outcome of my independent and personal research, all sources employed have been properly acknowledged both in the dissertation and on the reference list. I also certify that the work in this dissertation has not been submitted in whole or in part for any other degree in this University or in any institute of higher learning. ……………………………………………………… …….…. /………. /2019 Tapiwa Patson Sisimayi Date SUPERVISOR: Doctor Douglas Munemo iii DEDICATION To my son Tapiwa Jr. -

Newsletter Zimbabwe Issue 9 • February - May 2014

United Nations in Zimbabwe UnitedÊNationsÊ Newsletter Zimbabwe Issue 9 • February - May 2014 www.zw.one.un.org SPECIAL FOCUS Gender Equality IN THIS ISSUE The ninth edition of the United Nations in Zimbabwe newsletter is dedicated to PAGE 1 UN engagement in promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment Advancing Women’s Rights Through initiatives in Zimbabwe. This newsletter also highlights issues related to Constitutional Provisions health, skills, and human trafficking. Finally, this newsletter covers updates PAGE 3 on the development of the new Zimbabwe United Nations Development A Joint UN UnitedÊNationsÊ Programme to Assistance Framework (ZUNDAF) for 2016-2020, the UN’s partnership with Advance Women’s the Harare International Festival of Arts, and the Zimbabwe International Empowerment Trade Fair. PAGE 4 Refurbishing Maternity Waiting FEATURE ARTICLE: Homes to Enhance Zimbabwe Maternal Health Services Advancing Women’s Rights Through PAGE 5 “Not Yet Uhuru” in Realising Maternal Constitutional Provisions and Child Health Rights The new Constitution adopted Constitution provides the bedrock A special through a popular referendum in upon which systems and policies measure to PAGE 6 Promoting Gender 2013 was a major milestone in the can be built to enhance women’s increase women’s Equality Through history of Zimbabwe. Zimbabweans equal participation in all sectors of representation in Harnessing the Power from all walks of life participated society. Parliament, and of Radio in translating their individual and To mark this breakthrough for a provision for collective aspirations into a new achieving gender PAGE 7 women in the new Constitution, Empowering Women Supreme Law of the land. the national commemoration of balance in all and Youth With New public entities and Skills Women, both as individuals and the 2014 International Women’s as organized groups, actively Day was held under the theme, commissions are PAGE 8 participated in the constitution- “Celebrating Women’s Gains now part of the New Law in Place new Constitution. -

Women in the 7Th Parliament Current Position of Zimbabwean Women in Politics

WOMEN IN POLITICS SUPPORT UNIT Women in the 7th Parliament Current Position of Zimbabwean Women in Politics WiPSU Providing support to women in Parliament and Local Government in Zimbabwe aiming to increase women’s qualitative and quantitative participation and influence in policy and decision making. WOMEN LEGISLATORS IN THE 7TH SESSION OF THE ZIMBABWEAN PARLIAMENT Parliament of Zimbabwe 2008 • Women make up 20% of the 7th Parliament of Zimbabwe. • 55 women legislators in the 7th Parliament out of a total of 301 legislators. • 23 women in the Upper House (Senate). • 34 Women in the Lower House (House of Assembly). • Edna Madzongwe is the current Senate President. • Nomalanga Khumalo is the Deputy Speaker of Parliament. WOMEN IN THE UPPER HOUSE OF PARLIAMENT Current Position of Women Number of Political Name of Senator Women in Senate Party • 23 Women Senators out 1 Siphiwe Ncube MDC (M) of a total of 91. 2 Agnes Sibanda MDC(T) • Constitutionally 3 more 3 Gladys Dube MDC(T) Senators are yet to be appointed.( there might be 4 Enna Chitsa MDC(T) more after the negotiations are 5 Sekai Holland MDC(T) concluded) • Women constitute 25% of 6 Rorana Muchiwa MDC(T) 2008 Upper House 7 Monica Mutsvangwa ZANU PF • President of the Senate 8 Kersencia Chabuka MDC (T) is female 9 Getrude Chibhagu ZANU PF 10 Angeline Dete ZANU PF 11 Alice Chimbudzi ZANU PF 12 Jenia Manyeruke ZANU PF 13 Gladys Mabhuza ZANU PF Senate President Edna Madzongwe ZANU PF 14 15 Chiratidzo Gava ZANU PF 16 Viginia Katyamaenza ZANU PF 17 Imelda Mandaba ZANU PF 18 Tambudzani Mohadi ZANU PF 19 Sithembile Mlotshwa MDC (T) 20 Tariro Mutingwende ZANU PF 21 Virginia Muchenge ZANU PF 22 Angeline Masuku ZANU PF 23 Thokozile Mathuthu ZANU PF 2 |WiPSU [email protected] or [email protected] WOMEN IN THE LOWER HOUSE OF PARLIAMENT Current Position of Political Women No. -

Zimbabwe Domestic Broadcasting, 13 September, 2010 (3 September-12 September, 2010)

Zimbabwe Domestic Broadcasting, 13 September, 2010 (3 September-12 September, 2010) by Marie Lamensch, MIGS reporter for Zimbabwe (The Herald, government-owned daily, article dated September 6, 2009, in English) “Zimbabwe: Party of Excellence, My Foot!” by Frank Banda • A columnist for Talk Zimbabwe criticized the MDC-T for its corrupt councilors and for thinking that they can “repeat their electoral fluke” in the forthcoming elections. He also criticizes PM Morgan Tsvangirai for calling his party “a party of excellence” as the MDC-T‟s claims have not been back by action. • Reference is made to the MDC-T‟s parallel government and to Tvsangirai‟s demands to have a “peacekeeping force” monitor the next elections, although peacekeeping operations are reserved for conflict-ridden countries. The Prime Minister is criticized for lying to civil servants about their wages simply in an attempt to outshine President Mugabe. References are also made to Tsvangirai official residence, the MDC-T ministers‟ cards, Minister of Finance Tendai Biti‟s failure to consult a parliamentary committee concerning the budget. • The future elections will prove that the MDC-T is far from being the party of excellence (The Chronicle, government-owned daily, article dated September 7, 2009, in English) “MDC-T has failed to present credible challenge to Zanu-PF” by Nancy Lovedale • The MDC-T is described as an emerging political party that have sought to replace Zanu- PF and a party of “quid pro quo” desperate in its drive for power. • Independent media are criticized for siding with the MDC-T, for morphing into a propaganda machine “demonizing and criminalizing Zanu-PF.” • The MDC-T has failed to present a challenge to Zanu-PF and has no credible agenda. -

'Reporter Voice' and 'Objectivity'

THE ‘REPORTER VOICE’ AND ‘OBJECTIVITY’ IN CROSS- LINGUISTIC REPORTING OF ‘CONTROVERSIAL’ NEWS IN ZIMBABWEAN NEWSPAPERS. AN APPRAISAL APPROACH BY COLLEN SABAO Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University SUPERVISOR: PROF MW VISSER MARCH 2013 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 17 September 2012 Copyright © 2013 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za iii ABSTRACT The dissertation is a comparative analysis of the structural (generic/cognitive) and ideological properties of Zimbabwean news reports in English, Shona and Ndebele, focusing specifically on the examination of the proliferation of authorial attitudinal subjectivities in ‘controversial’ ‘hard news’ reports and the ‘objectivity’ ideal. The study, thus, compares the textuality of Zimbabwean printed news reports from the English newspapers (The Herald, Zimbabwe Independent and Newsday), the Shona newspaper (Kwayedza) and the Ndebele newspaper (Umthunywa) during the period from January 2010 to August 2012. The period represents an interesting epoch in the country’s political landscape. It is a period characterized by a power- sharing government, a political situation that has highly polarized the media and as such, media stances in relation to either of the two major parties to the unity government, the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU PF) and the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC-T). -

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe – ZWE37451 – Movement For

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe – ZWE37451 – Movement for Democratic Change (MDC-T) – Political violence – Police – Armed forces – MDC Split – Mashonaland West – Jephat Karemba 1 October 2010 1. Please provide the latest material update on the situation in Zimbabwe for members of the MDC and their treatment by ZANU PF and the police and military. Active members and supporters of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), and their families, continue to endure threats, violence, kidnappings, torture and killings at the hands of Zimbabwe‟s African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU PF) activists and, occasionally, at the hands of soldiers. There has been a decline in the numbers of attacks on MDC members since the formation of a unity government in late 2008; nevertheless, the overall number of incidents remains high. Historically, the level of violence in Zimbabwe has been cyclical and therefore it is highly plausible that violence and intimidation will escalate as the 2011 parliamentary election draws nearer. Another critical factor in the near future is the inevitable post-Mugabe political landscape; the behaviour of his replacement and the top ranks of the military are subjects of much speculation and will have a dramatic bearing on the treatment of MDC members and supporters into the future. Violent incidents perpetrated against opposition members and supporters have declined since the 2008 election campaign and the subsequent formation of the unity government. The US Department of State reports that in 2009 “at least 3,316 victims