Zimbabwe Country Report BTI 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Sanctions Zimbabwe

Canadian Sanctions and Canadian charities operating in Zimbabwe: Be Very Careful! By Mark Blumberg (January 7, 2009) Canadian charities operating in Zimbabwe need to be extremely careful. It is not the place for a new and inexperienced charity to begin foreign operations. In fact, only Canadian charities with substantial experience in difficult international operations should even consider operating in Zimbabwe. It is one of the most difficult countries to carry out charitable operations by virtue of the very difficult political, security, human rights and economic situation and the resultant Canadian and international sanctions. This article will set out some information on the Zimbabwe Sanctions including the full text of the Act and Regulations governing the sanctions. It is not a bad idea when dealing with difficult legal issues to consult knowledgeable legal advisors. Summary On September 4, 2008, the Special Economic Measures (Zimbabwe) Regulations (SOR/2008-248) (the “Regulations”) came into force pursuant to subsections 4(1) to (3) of the Special Economic Measures Act. The Canadian sanctions against Zimbabwe are targeted sanctions dealing with weapons, technical support for weapons, assets of designated persons, and Zimbabwean aircraft landing in Canada. There is no humanitarian exception to these targeted sanctions. There are tremendous practical difficulties working in Zimbabwe and if a Canadian charity decides to continue operating in Zimbabwe it is important that the Canadian charity and its intermediaries (eg. Agents, contractor, partners) avoid providing any benefits, “directly or indirectly”, to a “designated person”. Canadian charities need to undertake rigorous due diligence and risk management to ensure that a “designated person” does not financially benefit from the program. -

On the Shoulders of Struggle, Memoirs of a Political Insider by Dr

On the Shoulders of Struggle: Memoirs of a Political Insider On the Shoulders of Struggle: Memoirs of a Political Insider Dr. Obert M. Mpofu Dip,BComm,MPS,PhD Contents Preface vi Foreword viii Commendations xii Abbreviations xiv Introduction: Obert Mpofu and Self-Writing in Zimbabwe xvii 1. The Mind and Pilgrimage of Struggle 1 2. Childhood and Initiation into Struggle 15 3. Involvement in the Armed Struggle 21 4. A Scholar Combatant 47 5. The Logic of Being ZANU PF 55 6. Professional Career, Business Empire and Marriage 71 7. Gukurahundi: 38 Years On 83 8. Gukurahundi and Selective Amnesia 97 9. The Genealogy of the Zimbabwean Crisis 109 10. The Land Question and the Struggle for Economic Liberation 123 11. The Post-Independence Democracy Enigma 141 12. Joshua Nkomo and the Liberation Footpath 161 13. Serving under Mugabe 177 14. Power Struggles and the Military in Zimbabwe 205 15. Operation Restore Legacy the Exit of Mugabe from Power 223 List of Appendices 249 Preface Ordinarily, people live to either make history or to immortalise it. Dr Obert Moses Mpofu has achieved both dimensions. With wanton disregard for the boundaries of a “single story”, Mpofu’s submission represents a construction of the struggle for Zimbabwe with the immediacy and novelty of a participant. Added to this, Dr Mpofu’s academic approach, and the Leaders for Africa Network Readers’ (LAN) interest, the synergy was inevitable. Mpofu’s contribution, which philosophically situates Zimbabwe’s contemporary politics and socio-economic landscape, embodies LAN Readers’ dedication to knowledge generation and, by extension, scientific growth. -

Article a Very Zimbabwean Coup

Article A very Zimbabwean coup: November 13-24, 2017 David Moore [email protected] Abstract Toward the end of 2017 Robert Mugabe was convinced by members of his own party and leaders of the military to retire from his 37 year presidency of Zimbabwe. That one report called the process hastening his departure an ‘unexpected but peaceful transition’ suggests that what more impartial observers call a coup nonetheless had special characteristics softening its military tenor. This exploratory article discusses some of the particularities of this ‘coup of a special type’, as well as considering the new light it shines on the political history of Zimbabwe, the party ruling it since 1980, and their future. The title of the novel A Very British Coup (authored in 1982 by a Bennite Labour politician who in 2003-5 became British Minister for Africa, and later made into two television series – Mullin 1982, Gallagher 2009:440) reminds us that just as every country’s politics has its particularities so too do their coups. Coups are a variant of Clausewitz’s dictum (come to think of it, Gramsci’s too – Moore 2014b) about the continuum of coercion and consent in the processes constituting one of humankind’s oldest professions. When accompanied by d’état the word indicates a quick and often forceful change of people governing in a state. The successful protagonists are usually rooted in the military. The state remains relatively intact and unchanged, as do the deeper social and economic structures on which it sits, condensing, reflecting, and refracting them while it ostensibly rules. -

Enreporting on Zimbabwe's 2018 Elections

Reporting on Zimbabwe’s 2018 elections A POST-ELECTION ANALYSIS Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1 PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS 8 2.0 MEDIA MONITORING OF THE NEWS AGENDA 8 3.0 MONITORING POLITICAL PLURALISM 13 4.0 GENDER REPRESENTATION DURING THE 2018 ELECTIONS 18 5.0 MEDIA CONDUCT IN ELECTION PROGRAMMING - BROADCAST MEDIA 24 6.0 MEDIA’S CONDUCT IN ELECTION REPORTING 28 7.0 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 34 ANNEX 1: HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS REPORTED IN THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA 35 ANNEX 2: LIST OF ACRONYMS 37 REPORTING ON ZIMBABWE’S 2018 ELECTIONS - A POST-ELECTION ANALYSIS i Acknowledgements International Media Support and the Media Alliance of Zimbabwe This publication has been produced with the assistance of the are conducting the programme “Support to media on governance European Union and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. and electoral matters in Zimbabwe”. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Media Monitors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views The programme is funded by the European Union and the of the European Union or the Norwegian Ministry of Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Foreign Affairs. International Media Support (IMS) is a non-profit organisation working with media in countries affected by armed conflict, human insecurity and political transition. ii REPORTING ON ZIMBABWE’S 2018 ELECTIONS - A POST-ELECTION ANALYSIS Executive Summary Zimbabwe’s 2018 harmonised national elections presented a irregularities, they struggled to clearly articulate the implications unique opportunity for the media and their audiences alike. In of the irregularities they reported and the allegations of previous election periods, the local media received severe criticism maladministration levelled against the country’s election for their excessively partisan positions, which had been characterized management body, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC). -

A Comparative Study of Zimbabwe and South Africa

FACEBOOK, YOUTH AND POLITICAL ACTION: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ZIMBABWE AND SOUTH AFRICA A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MEDIA STUDIES, RHODES UNIVERSITY by Admire Mare September 2015 ABSTRACT This comparative multi-sited study examines how, why and when politically engaged youths in distinctive national and social movement contexts use Facebook to facilitate political activism. As part of the research objectives, this study is concerned with investigating how and why youth activists in Zimbabwe and South Africa use the popular corporate social network site for political purposes. The study explores the discursive interactions and micro- politics of participation which plays out on selected Facebook groups and pages. It also examines the extent to which the selected Facebook pages and groups can be considered as alternative spaces for political activism. It also documents and analyses the various kinds of political discourses (described here as digital hidden transcripts) which are circulated by Zimbabwean and South African youth activists on Facebook fan pages and groups. Methodologically, this study adopts a predominantly qualitative research design although it also draws on quantitative data in terms of levels of interaction on Facebook groups and pages. Consequently, this study engages in data triangulation which allows me to make sense of how and why politically engaged youths from a range of six social movements in Zimbabwe and South Africa use Facebook for political action. In terms of data collection techniques, the study deploys social media ethnography (online participant observation), qualitative content analysis and in-depth interviews. -

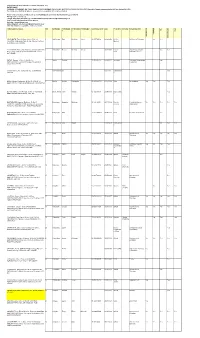

Updated Sanctions List

Compiled List of 349 Individuals on various 'Sanctions' lists. DATA FORMAT: SURNAME, FORENAMES, NATIONAL IDENTIFICATION NUMBER; DATE OF BIRTH;POSITION; ORGANISATION; LISTS (Australia, Canada, European Union EU, New Zealand NZ, USA. The List includes individuals who are deceased and occupational data may be outdated. Please send corrections, additions, etc to: [email protected] and to the implementing governments EU: http://eur-lex.europa.eu Canada: http://www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/trade/zimbabwe-en.asp [email protected] New Zealand: http://www.immigration.govt.nz Australia: [email protected] United Kingdom: [email protected] USA: http://www.treas.gov/offices/enforcement/ofac D CONSOLIDATED DATA REF SURNAME FORENAME FORENAME FORENAME 3 NATIONAL ID NO DoB POSITION SPOUSE ORGANISATION EU 1 2 USA CANADA AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAN ABU BASUTU, Titus Mehliswa Johna. ID No: 63- 1 Abu Basutu Titus Mehliswa Johna 63-375701F28 02/06/1956 Air Vice- Air Force of Zimbabwe Yes Yes 375701F28. DOB:02/06/1956. Air Vice-Marshal; Air Force Marshal of Zimbabwe LIST: CAN/EU/ AL SHANFARI, Thamer Bin Said Ahmed. DOB:30/01/1968. 2 Al Shanfari Thamer Bin Said Ahmed 30/01/1968 Former Oryx Group and Oryx Yes Yes Former Chair; Oryx Group and Oryx Natural Resources Chair Natural Resources LIST: EU/NZ/ BARWE, Reuben . ID No: 42- 091874L42. 3 Barwe Reuben 42- 091874L42 19/03/1953 Journalist Zimbabwe Broadcasting Yes DOB:19/03/1953. Journalist; Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation Corporation LIST: EU/ BEN-MENASHE, Ari . DOB:circa 1951. Businessman; 4 Ben-Menashe Ari circa 1951 Businessma Yes LIST: NZ/ n BIMHA, Michael Chakanaka . -

India Zimbabwe Relations

India Zimbabwe Relations India and Zimbabwe have a long history of close and cordial relations. During the era of the Munhumutapa Kingdom, Indian merchants established strong links with Zimbabwe, trading in textiles, minerals and metals. Sons of the royal house of Munhumutapa journeyed to India to broaden their education. In the 17th century, a great son of Zimbabwe, Dom Miguel – Prince, Priest and Professor, and heir to the imperial throne of the Mutapas – studied in Goa. An inscribed pillar stands today at a chapel in Goa, a tribute to his intellectual stature. India supported Zimbabwe’s freedom struggle. Former Prime Minister Smt. Indira Gandhi attended Zimbabwean independence celebrations in 1980. There were frequent exchanges of high level visits in the past, bilateral or to attend Summits such as NAM, CHOGM and G-15. Former Prime Minister Shri Vajpayee and President Mugabe met twice in the year 2003 on the sidelines of UNGA and NAM Summit. Former President Mugabe attended the IAFS-III held Delhi in 2015. Visits from India to Zimbabwe 1980 – Prime Minister Smt. Indira Gandhi – to attend Independence Celebrations of Zimbabwe. 1986 – Prime Minister Shri Rajiv Gandhi to attend NAM Summit. 1989 – President Shri R. Venkataraman 1991 – Prime Minister Shri Narasimha Rao – to attend CHOGM Summit 1995 – President Dr. S. D. Sharma 1996 – Prime Minister Shri H. D. Deve Gowda for the G-15 Summit 2018 - Vice President, Shri Venkaiah Naidu- Official Visit Visits from Zimbabwe to India 1981 – President Robert Gabriel Mugabe 1983 – President Robert Gabriel Mugabe to attend CHOGM and NAM Summits 1987 – President Mugabe – Africa Fund Summit 1991 – President Mugabe – Nehru Award Presentation 1993 – President Mugabe 1994 – President Mugabe – G-15 Summit 2015 – President Mugabe – IAFS-III Summit 2018 - Vice President General(Retd) Dr. -

The Mortal Remains: Succession and the Zanu Pf Body Politic

THE MORTAL REMAINS: SUCCESSION AND THE ZANU PF BODY POLITIC Report produced for the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum by the Research and Advocacy Unit [RAU] 14th July, 2014 1 CONTENTS Page No. Foreword 3 Succession and the Constitution 5 The New Constitution 5 The genealogy of the provisions 6 The presently effective law 7 Problems with the provisions 8 The ZANU PF Party Constitution 10 The Structure of ZANU PF 10 Elected Bodies 10 Administrative and Coordinating Bodies 13 Consultative For a 16 ZANU PF Succession Process in Practice 23 The Fault Lines 23 The Military Factor 24 Early Manoeuvring 25 The Tsholotsho Saga 26 The Dissolution of the DCCs 29 The Power of the Politburo 29 The Powers of the President 30 The Congress of 2009 32 The Provincial Executive Committee Elections of 2013 34 Conclusions 45 Annexures Annexure A: Provincial Co-ordinating Committee 47 Annexure B : History of the ZANU PF Presidium 51 2 Foreword* The somewhat provocative title of this report conceals an extremely serious issue with Zimbabwean politics. The theme of succession, both of the State Presidency and the leadership of ZANU PF, increasingly bedevils all matters relating to the political stability of Zimbabwe and any form of transition to democracy. The constitutional issues related to the death (or infirmity) of the President have been dealt with in several reports by the Research and Advocacy Unit (RAU). If ZANU PF is to select the nominee to replace Robert Mugabe, as the state constitution presently requires, several problems need to be considered. The ZANU PF nominee ought to be selected in terms of the ZANU PF constitution. -

China and Zimbabwe: the Context and Contents of a Complex Relationship

CHINA & ZIMBABWE: CONTEXT & CONTENTS OF A COMPLEX RELATIONSHIP OCCASIONAL PAPER 202 Global Powers and Africa Programme October 2014 China and Zimbabwe: The Context and Contents of a Complex Relationship Abiodun Alao s ir a f f A l a n o ti a rn e nt f I o te tu sti n In rica . th Af hts Sou sig al in Glob African perspectives. ABOUT SAIIA The South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) has a long and proud record as South Africa’s premier research institute on international issues. It is an independent, non-government think tank whose key strategic objectives are to make effective input into public policy, and to encourage wider and more informed debate on international affairs, with particular emphasis on African issues and concerns. It is both a centre for research excellence and a home for stimulating public engagement. SAIIA’s occasional papers present topical, incisive analyses, offering a variety of perspectives on key policy issues in Africa and beyond. Core public policy research themes covered by SAIIA include good governance and democracy; economic policymaking; international security and peace; and new global challenges such as food security, global governance reform and the environment. Please consult our website http://www.saiia.org.za for further information about SAIIA’s work. ABOUT THE GLOBA L POWERS A ND A FRICA PROGRA MME The Global Powers and Africa (GPA) Programme, formerly Emerging Powers and Africa, focuses on the emerging global players China, India, Brazil, Russia and South Africa as well as the advanced industrial powers such as Japan, the EU and the US, and assesses their engagement with African countries. -

Zimbabwe: Women Fearing Gender- Based Harm Or Violence

Country Policy and Information Note Zimbabwe: Women fearing gender- based harm or violence Version 2.0 February 2017 Preface This note provides country of origin information (COI) and policy guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the policy guidance contained with this note; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information The COI within this note has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. Feedback Our goal is to continuously improve our material. Therefore, if you would like to comment on this note, please email the Country Policy and Information Team. -

B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 314/2004 of 19 February 2004 Concerning Certain Restrictive Measures in Respect of Zimbabwe

2004R0314 — EN — 03.03.2010 — 010.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 314/2004 of 19 February 2004 concerning certain restrictive measures in respect of Zimbabwe (OJ L 55, 24.2.2004, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/2004 of 20 August 2004 L 273 12 21.8.2004 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 898/2005 of 15 June 2005 L 153 9 16.6.2005 ►M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1272/2005 of 1 August 2005 L 201 40 2.8.2005 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1367/2005 of 19 August 2005 L 216 6 20.8.2005 ►M5 Council Regulation (EC) No 1791/2006 of 20 November 2006 L 363 1 20.12.2006 ►M6 Commission Regulation (EC) No 236/2007 of 2 March 2007 L 66 14 6.3.2007 ►M7 Commission Regulation (EC) No 412/2007 of 16 April 2007 L 101 6 18.4.2007 ►M8 Commission Regulation (EC) No 777/2007 of 2 July 2007 L 173 3 3.7.2007 ►M9 Commission Regulation (EC) No 702/2008 of 23 July 2008 L 195 19 24.7.2008 ►M10 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1226/2008 of 8 December 2008 L 331 11 10.12.2008 ►M11 Commission Regulation (EC) No 77/2009 of 26 January 2009 L 23 5 27.1.2009 ►M12 Commission Regulation (EU) No 173/2010 of 25 February 2010 L 51 13 2.3.2010 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 46, 17.2.2009, p. -

Newsletter Zimbabwe Issue 9 • February - May 2014

United Nations in Zimbabwe UnitedÊNationsÊ Newsletter Zimbabwe Issue 9 • February - May 2014 www.zw.one.un.org SPECIAL FOCUS Gender Equality IN THIS ISSUE The ninth edition of the United Nations in Zimbabwe newsletter is dedicated to PAGE 1 UN engagement in promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment Advancing Women’s Rights Through initiatives in Zimbabwe. This newsletter also highlights issues related to Constitutional Provisions health, skills, and human trafficking. Finally, this newsletter covers updates PAGE 3 on the development of the new Zimbabwe United Nations Development A Joint UN UnitedÊNationsÊ Programme to Assistance Framework (ZUNDAF) for 2016-2020, the UN’s partnership with Advance Women’s the Harare International Festival of Arts, and the Zimbabwe International Empowerment Trade Fair. PAGE 4 Refurbishing Maternity Waiting FEATURE ARTICLE: Homes to Enhance Zimbabwe Maternal Health Services Advancing Women’s Rights Through PAGE 5 “Not Yet Uhuru” in Realising Maternal Constitutional Provisions and Child Health Rights The new Constitution adopted Constitution provides the bedrock A special through a popular referendum in upon which systems and policies measure to PAGE 6 Promoting Gender 2013 was a major milestone in the can be built to enhance women’s increase women’s Equality Through history of Zimbabwe. Zimbabweans equal participation in all sectors of representation in Harnessing the Power from all walks of life participated society. Parliament, and of Radio in translating their individual and To mark this breakthrough for a provision for collective aspirations into a new achieving gender PAGE 7 women in the new Constitution, Empowering Women Supreme Law of the land. the national commemoration of balance in all and Youth With New public entities and Skills Women, both as individuals and the 2014 International Women’s as organized groups, actively Day was held under the theme, commissions are PAGE 8 participated in the constitution- “Celebrating Women’s Gains now part of the New Law in Place new Constitution.