Togolese Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Legal Regimes to Protect the World's Grasslands / John W

00 head grasslands final 9/28/12 1:47 PM Page i Global Legal Regimes to Protect the World’s Grasslands 00 head grasslands final 9/28/12 1:47 PM Page ii 00 head grasslands final 9/28/12 1:47 PM Page iii Global Legal Regimes to Protect the World’s Grasslands John W. Head Robert W. Wagstaff Distinguished Professor of Law University of Kansas School of Law Lawrence, Kansas Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina 00 head grasslands final 9/28/12 1:47 PM Page iv Copyright © 2012 John W. Head All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Head, John W. (John Warren), 1953- Global legal regimes to protect the world's grasslands / John W. Head. p. cm. ISBN 978-1-59460-967-1 (alk. paper) 1. Grasslands--Law and legislation. I. Title. K3520.H43 2012 346.04'4--dc23 2012016506 Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America 00 head grasslands final 9/28/12 1:47 PM Page v Summary of Contents Part One Grasslands at Risk Chapter 1 • The Character and Location of the World’s Grasslands and Prairies 3 I. Locations of Grasslands in the World 4 II. Character and Definitions of Grasslands 17 Chapter 2 • How Are the Grasslands at Risk, and Why Should We Care? 39 I. Degradation and Destruction of the World’s Grasslands 39 II. What Good Are Grasslands? 57 III. Closing Comments for Part One 63 Part Two Current Legal Regimes Pertaining to Grasslands Chapter 3 • National and Provincial Measures for Grasslands Protection 67 I. -

Investigating Grasslands All Across the World from ESRI India Geo-Inquiry Team

Investigating Grasslands all across the world From ESRI India Geo-Inquiry Team Target Audience: Class 9 Geography Students Time required: 1 hour and 10 Minutes Indicator: Understand the presence of Grasslands all across the world and learn about them on real maps. Learning Outcomes: Students will analyze the Grasslands all across the world using web-based mapping tools to: 1–Symbolize and classify a map of the grasslands of the world based on their division, formation and name. 2–Examine a table of the largest grasslands of the world with details of name, division and formation. 3– Understand the relationship between individual grassland and the larger grasslands in which individual grasslands exist. 4– Examine which regions of the world has grasslands and where in India Grasslands are found. 5– Understand the differences between division, formation and different individual grasslands. 6– Understand how grasslands have sustained the ecology of earth and its contribution towards the biosphere. Map URL: https://arcg.is/1SHvj0 Can you better understand the importance of grasslands in the world? Can you better understand characteristics of the world’s major grasslands, including their locations, division, formation, and countries in which it is spread out? Can you determine the effect of grasslands in the ecology and biosphere of the earth? Teacher Notes This is a discovery type of investigation. Students use live web mapping services in an online Geographic Information System (GIS) and use real data about rivers around the world. Students will investigate four themes of geography in this activity: 1. Patterns of grasslands all across the world. -

Distribution Mapping of World Grassland Types A

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2014) SYNTHESIS Distribution mapping of world grassland types A. P. Dixon1*, D. Faber-Langendoen2, C. Josse2, J. Morrison1 and C. J. Loucks1 1World Wildlife Fund – United States, 1250 ABSTRACT 24th Street NW, Washington, DC 20037, Aim National and international policy frameworks, such as the European USA, 2NatureServe, 4600 N. Fairfax Drive, Union’s Renewable Energy Directive, increasingly seek to conserve and refer- 7th Floor, Arlington, VA 22203, USA ence ‘highly biodiverse grasslands’. However, to date there is no systematic glo- bal characterization and distribution map for grassland types. To address this gap, we first propose a systematic definition of grassland. We then integrate International Vegetation Classification (IVC) grassland types with the map of Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World (TEOW). Location Global. Methods We developed a broad definition of grassland as a distinct biotic and ecological unit, noting its similarity to savanna and distinguishing it from woodland and wetland. A grassland is defined as a non-wetland type with at least 10% vegetation cover, dominated or co-dominated by graminoid and forb growth forms, and where the trees form a single-layer canopy with either less than 10% cover and 5 m height (temperate) or less than 40% cover and 8 m height (tropical). We used the IVC division level to classify grasslands into major regional types. We developed an ecologically meaningful spatial cata- logue of IVC grassland types by listing IVC grassland formations and divisions where grassland currently occupies, or historically occupied, at least 10% of an ecoregion in the TEOW framework. Results We created a global biogeographical characterization of the Earth’s grassland types, describing approximately 75% of IVC grassland divisions with ecoregions. -

Workingpaper

WORKINGPAPER UNU-EHS PUBLICATION SERIES No. 11 | July 2015 Towards the Development of an Adapted Multi-hazard Risk Assessment Framework for the West Sudanian Savanna Zone Julia Kloos, Daniel Asare-Kyei, Joanna Pardoe and Fabrice G. Renaud INSTITUTE FOR ENVIRONMENT AND HUMAN SECURITY (UNU-EHS) UN UNIVERSITY SPONSORED BY THE THROUGH UNU-EHS Institute for Environment and Human Security TOWARDS THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN ADAPTED MULTI-HAZARD RISK ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK FOR THE WEST SUDANIAN SAVANNA ZONE Abstract West Africa is a region considered highly vulnerable to climate change and associated with natural hazards due to interactions of climate change and non-climatic stressors exacerbating the vulnerability of the region, particularly its agricultural system (IPCC, 2014b). Taking the Western Sudanian Savanna as our geographic target area, this paper seeks to develop an integrated risk assessment framework that incorporates resilience as well as multiple hazards concepts, and is applicable to the specific conditions of the target area. To provide the scientific basis for the framework, the paper will first define the following key terms of risk assessments in a climate change adaptation context: risk, hazard, exposure, vulnerability, resilience, coping and adaptation. Next, it will discuss the ways in which they are conceptualized and employed in risk, resilience and vulnerability frameworks. When reviewing the literature on existing indicator-based risk assessment for West African Sudanian Savanna zones, it becomes apparent that there is a lack of a systematic and comprehensive risk assessment capturing multiple natural hazards. The paper suggests an approach for linking resilience and vulnerability in a common framework for risk assessment. -

The BIOTA Biodiversity Observatories in Africa—A Standardized Framework for Large-Scale Environmental Monitoring

Environ Monit Assess DOI 10.1007/s10661-011-1993-y The BIOTA Biodiversity Observatories in Africa—a standardized framework for large-scale environmental monitoring Norbert Jürgens · Ute Schmiedel · Daniela H. Haarmeyer · Jürgen Dengler · Manfred Finckh · Dethardt Goetze · Alexander Gröngröft · Karen Hahn · Annick Koulibaly · Jona Luther-Mosebach · Gerhard Muche · Jens Oldeland · Andreas Petersen · Stefan Porembski · Michael C. Rutherford · Marco Schmidt · Brice Sinsin · Ben J. Strohbach · Adjima Thiombiano · Rüdiger Wittig · Georg Zizka Received: 4 August 2010 / Accepted: 23 February 2011 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V 2011 Abstract The international, interdisciplinary bio- BIOTA Biodiversity Observatories, that meet the diversity research project BIOTA AFRICA ini- following criteria (a) enable long-term monitor- tiated a standardized biodiversity monitoring ing of biodiversity, potential driving factors, and network along climatic gradients across the relevant indicators with adequate spatial and tem- African continent. Due to an identified lack of poral resolution, (b) facilitate comparability of adequate monitoring designs, BIOTA AFRICA data generated within different ecosystems, (c) developed and implemented the standardized allow integration of many disciplines, (d) allow Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10661-011-1993-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users. N. Jürgens · U. Schmiedel (B) · D. H. Haarmeyer · A. Koulibaly J. Dengler · M. Finckh · J. Luther-Mosebach · Laboratoire de Production et Amélioration Végétales, G. Muche · J. Oldeland U.F.R. Sciences de la Nature, Université Biodiversity, Evolution and Ecology of Plants, d’Abobo-Adjamé, URES Daloa, 02, Biocentre Klein Flottbek and Botanical Garden, BP 150 Daloa 02, Côte d’Ivoire University of Hamburg, Ohnhorststr. -

Projected Changes in the Amplitude of Future El Niño Type of Events

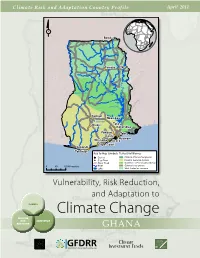

Climate Risk and Adaptation Country Profile April 2011 N Bawku !( Yendi !(Tamale !( Banda Nwanta Lake Volta !(Kumasi !(Nkawkaw Bosumtwi Tafo !( Obuasi !( !( Koforidua Pokoasi !( Tema !( !( Teshi !( .! Nsawam Winneba !( Accra !(Cape Coast Sekondi !(!( Takoradi Key to Map Symbols Terrestrial Biomes Capital Central African mangroves City/Town Eastern Guinean forests Major Road Guinean forest-savanna mosaic 0 60 120 Kilometers River Guinean mangroves Lake West Sudanian savanna Vulnerability, Risk Reduction, and Adaptation to CLIMATE Climate Change DISASTER RISK ADAPTATION REDUCTION GHANA Climate Climate Change Team Investment Funds ENV Climate Risk and Adaptation Country Profile Ghana Climate Risk and Adaptation Country Profile COUNTRY OVERVIEW Ghana is located in West Africa and shares borders with Togo on the east, Burkina Faso to the north, La Cote D’Ivoire on the west and the Gulf of Guinea to the south. Ghana covers an area of 238,500 km2. The country is relatively well endowed with water: extensive water bodies, including Lake Volta and Bosomtwi, occupy 3,275 km2, while seasonal and perennial rivers occupy another 23,350 square kilometers. Ghana's population is about 23.8 million (2009)1 and is estimated to be increasing at a rate of 2.1% per annum. Life expectancy is 56 years and infant mortality rate is 69 per thousand life births. Ghana is classified as a developing country with a per capita income of US$ 1098 (2009). Agriculture and livestock constitute the mainstay of Ghana’s economy, accounting for 32% of GDP in 2009 and employing 55% of the economically active population2. Agriculture is predominantly rainfed, which exposes it to the effects of present climate variability and the risks of future climate change. -

Tropical Grasslands--Trends, Perspectives and Future Prospects

University of Kentucky UKnowledge International Grassland Congress Proceedings XXIII International Grassland Congress Tropical Grasslands--Trends, Perspectives and Future Prospects Panjab Singh FAARD Foundation, India Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/igc Part of the Plant Sciences Commons, and the Soil Science Commons This document is available at https://uknowledge.uky.edu/igc/23/plenary/8 The XXIII International Grassland Congress (Sustainable use of Grassland Resources for Forage Production, Biodiversity and Environmental Protection) took place in New Delhi, India from November 20 through November 24, 2015. Proceedings Editors: M. M. Roy, D. R. Malaviya, V. K. Yadav, Tejveer Singh, R. P. Sah, D. Vijay, and A. Radhakrishna Published by Range Management Society of India This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Plant and Soil Sciences at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Grassland Congress Proceedings by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Plenary Lecture 7 Tropical grasslands –trends, perspectives and future prospects Panjab Singh President, FAARD Foundation, Varanasi and Ex Secretary, DARE and DG, ICAR, New Delhi, India E-mail : [email protected] Grasslands are the area covered by vegetation accounts for 50–80 percent of GDP (World Bank, 2007). dominated by grasses, with little or no tree cover. Central and South America provide 39 percent of the UNESCO defined grassland as “land covered with world’s meat production from grassland-based herbaceous plants with less than 10 percent tree and systems, and sub-Saharan Africa holds a 12.5 percent shrub cover” and wooded grassland as 10-40 percent share. -

A Spatial Analysis Approach to the Global Delineation of Dryland Areas of Relevance to the CBD Programme of Work on Dry and Subhumid Lands

A spatial analysis approach to the global delineation of dryland areas of relevance to the CBD Programme of Work on Dry and Subhumid Lands Prepared by Levke Sörensen at the UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK January 2007 This report was prepared at the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). The lead author is Levke Sörensen, scholar of the Carlo Schmid Programme of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). Acknowledgements This report benefited from major support from Peter Herkenrath, Lera Miles and Corinna Ravilious. UNEP-WCMC is also grateful for the contributions of and discussions with Jaime Webbe, Programme Officer, Dry and Subhumid Lands, at the CBD Secretariat. Disclaimer The contents of the map presented here do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. 3 Table of contents Acknowledgements............................................................................................3 Disclaimer ...........................................................................................................3 List of tables, annexes and maps .....................................................................5 Abbreviations -

Land Cover Characterization in West Sudanian Savannas Using Seasonal Features from Annual Landsat Time Series

remote sensing Article Land Cover Characterization in West Sudanian Savannas Using Seasonal Features from Annual Landsat Time Series Jinxiu Liu 1,*, Janne Heiskanen 1, Ermias Aynekulu 2, Eduardo Eiji Maeda 1 and Petri K. E. Pellikka 1 1 Department of Geosciences and Geography, P.O. Box 68, University of Helsinki, FI-00014 Helsinki, Finland; janne.heiskanen@helsinki.fi (J.H.); eduardo.maeda@helsinki.fi (E.E.M.); petri.pellikka@helsinki.fi (P.K.E.P.) 2 World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), United Nations Avenue, P.O. Box 30677, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya; [email protected] * Correspondence: jinxiu.liu@helsinki.fi; Tel.: +358-294-151-584 Academic Editors: Lars Eklundh, James Campbell and Prasad S. Thenkabail Received: 22 January 2016; Accepted: 21 April 2016; Published: 28 April 2016 Abstract: With the increasing temporal resolution of medium spatial resolution data, seasonal features are becoming more readily available for land cover characterization. However, in the tropical regions, images can be severely contaminated by clouds during the rainy season and fires during the dry season, with possible effects to seasonal features. In this study, we evaluated the performance of seasonal features based on an annual Landsat time series (LTS) of 35 images for land cover characterization in West Sudanian savanna woodlands. First, the burnt areas were detected and removed. Second, the reflectance seasonality was modelled using a harmonic model, and model parameters were used as inputs for land cover classification and tree crown cover prediction using the random forest algorithm. Furthermore, to study the sensitivity of the approach to the burnt areas, we repeated the analyses without the first step. -

Larger Than Elephants

Framework Contract COM 2011 – Lot 1 Request for Services 2013/328436 - Version 1 Larger than elephants Inputs for the design of an EU Strategic Approach to Wildlife Conservation in Africa Volume 5 Western Africa December 2014 Ce projet est financé par l’Union Européenne Mis en œuvre par AGRER – Consortium B&S Volume 5 WEST AFRICA Inputs for the design of an EU strategic approach to wildlife conservation in Africa Page 1 Final report Volume 5 WEST AFRICA TABLE OF CONTENTS 0. RATIONALE ..................................................................................................................................................................... 9 1. SPECIAL FEATURES OF WEST AFRICA .................................................................................................................... 13 1.1 COUNTRIES OF WEST AFRICA .................................................................................................................................. 13 1.1.1 Development indicators ........................................................................................................................................................ 13 1.1.2 Conflict .................................................................................................................................................................................. 15 1.1.3 Food crisis ............................................................................................................................................................................ 15 1.1.4 West -

2016 Adhikari Pradeep Dissert

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE MAPPING AND ANALYZING URBAN GROWTH: A STUDY TO IDENTIFY DRIVERS OF URBAN GROWTH IN WEST AFRICA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By PRADEEP ADHIKARI Norman, Oklahoma 2016 MAPPING AND ANALYZING URBAN GROWTH: A STUDY TO IDENTIFY DRIVERS OF URBAN GROWTH IN WEST AFRICA A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY BY ______________________________ Dr. Kirsten M. de Beurs, Chair ______________________________ Dr. David Sabatini ______________________________ Dr. Renee McPherson ______________________________ Dr. Aondover Tarhule ______________________________ Dr. Yang Hong © Copyright by PRADEEP ADHIKARI 2016 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Dr. Kirsten M. de Beurs for the continuous support during my Ph.D. study and research, for her patience, and for her motivation. Her guidance steered me on the right path in this journey. Thank you Dr. de Beurs! I would like to extend my sincere thanks to the rest of my committee members: Dr. David Sabatini, Dr. Renee McPherson, Dr. Aondover Tarhule, and Dr. Yang Hong for their insightful questions and encouragement along the way. Such questions and probing helped me to widen my research from various perspectives. I also thank my fellow students from the Landscape Land Use Change Institute for the stimulating discussions and comments on my research, presentations and write-ups. Additionally, I would also like to extend my gratitude to the faculty, staff and students of the department for their support and help, directly or indirectly during my graduate study. -

Status, Trends and Future Dynamics of Biodiversity and Ecosystems Underpinning Nature’S Contributions to People 1

CHAPTER 3 . STATUS, TRENDS AND FUTURE DYNAMICS OF BIODIVERSITY AND ECOSYSTEMS UNDERPINNING NATURE’S CONTRIBUTIONS TO PEOPLE 1 CHAPTER 2 CHAPTER 3 STATUS, TRENDS AND CHAPTER FUTURE DYNAMICS OF BIODIVERSITY AND 3 ECOSYSTEMS UNDERPINNING NATURE’S CONTRIBUTIONS CHAPTER TO PEOPLE 4 Coordinating Lead Authors Review Editors: Marie-Christine Cormier-Salem (France), Jonas Ngouhouo-Poufoun (Cameroon) Amy E. Dunham (United States of America), Christopher Gordon (Ghana) This chapter should be cited as: CHAPTER Cormier-Salem, M-C., Dunham, A. E., Lead Authors Gordon, C., Belhabib, D., Bennas, N., Dyhia Belhabib (Canada), Nard Bennas Duminil, J., Egoh, B. N., Mohamed- (Morocco), Jérôme Duminil (France), Elahamer, A. E., Moise, B. F. E., Gillson, L., 5 Benis N. Egoh (Cameroon), Aisha Elfaki Haddane, B., Mensah, A., Mourad, A., Mohamed Elahamer (Sudan), Bakwo Fils Randrianasolo, H., Razafindratsima, O. H., 3Eric Moise (Cameroon), Lindsey Gillson Taleb, M. S., Shemdoe, R., Dowo, G., (United Kingdom), Brahim Haddane Amekugbe, M., Burgess, N., Foden, W., (Morocco), Adelina Mensah (Ghana), Ahmim Niskanen, L., Mentzel, C., Njabo, K. Y., CHAPTER Mourad (Algeria), Harison Randrianasolo Maoela, M. A., Marchant, R., Walters, M., (Madagascar), Onja H. Razafindratsima and Yao, A. C. Chapter 3: Status, trends (Madagascar), Mohammed Sghir Taleb and future dynamics of biodiversity (Morocco), Riziki Shemdoe (Tanzania) and ecosystems underpinning nature’s 6 contributions to people. In IPBES (2018): Fellow: The IPBES regional assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services for Gregory Dowo (Zimbabwe) Africa. Archer, E., Dziba, L., Mulongoy, K. J., Maoela, M. A., and Walters, M. (eds.). CHAPTER Contributing Authors: Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Millicent Amekugbe (Ghana), Neil Burgess Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity (United Kingdom), Wendy Foden (South and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, Germany, Africa), Leo Niskanen (Finland), Christine pp.