Conjecture on the Function of the Robertsbridge Codex Estampies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Odo of Cluny Catholic.Net

St. Odo of Cluny Catholic.net Born to the nobility, the son of Abbo. Raised in the courts of Count Fulk II of Anjou and Duke William of Aquitaine. Received the Order of Tonsure at age nineteen. Canon of the church of Saint Martin of Tours. Studied music and theology in Paris for four years, studying under Remigius of Auxerre. Returning home, he spent years as a near-hermit in a cell, studying and praying. Benedictine monk at Baume, diocese of Besancon, France in 909, bringing all his worldly possessions – a library of about 100 books. Spiritual student of the abbot, Saint Berno of Cluny. Headmaster of the monastery school at Baume. Abbot of Baume in 924. Abbot of Cluny, Massey and Deols in 927. In 931, Pope John XI asked Odo to reform all the monasteries in the Aquitaine, northern France and Italy. Negotiated a peace between Heberic of Rome and Hugh of Provence in 936; returned twice in six years to renegotiate the peace between them. Persuaded many secular leaders to give up control of monasteries so they could return to being spiritual centers, not sources of cash for the state. Founded the monastery of Our Lady on the Aventine in Rome. Wrote a biography of Saint Gerald of Aurillac, three books of essays on morality, some homilies, an epic poem on the Redemption, and twelve choral antiphons in honour of Saint Martin of Tours. Noted for his knowledge, his administrative abilities, his skills as a reformer, and as a writer; also known for his charity, he has been depicted giving the poor the clothes off his back. -

Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant As Corporate Knowledge

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2012 "Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge Jordan Timothy Ray Baker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Epistemology Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Jordan Timothy Ray, ""Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1360 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jordan Timothy Ray Baker entitled ""Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Rachel M. Golden, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: -

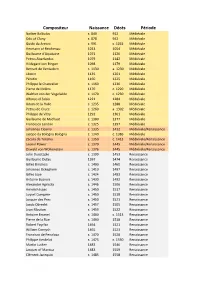

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected]

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected] List of Addendums First Addendum – Middle Ages Second Addendum – Modern and Modern Sub-Categories A. 20th Century B. 21st Century C. Modern and High Modern D. Postmodern and Contemporary E. Descrtiption of Categories (alphabetic) and Important Composers Third Addendum – Composers Fourth Addendum – Musical Terms and Concepts 1 First Addendum – Middle Ages A. The Early Medieval Music (500-1150). i. Early chant traditions Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian Church. The simplest, syllabic chants, in which each syllable is set to one note, were probably intended to be sung by the choir or congregation, while the more florid, melismatic examples (which have many notes to each syllable) were probably performed by soloists. Plainchant melodies (which are sometimes referred to as a “drown,” are characterized by the following: A monophonic texture; For ease of singing, relatively conjunct melodic contour (meaning no large intervals between one note and the next) and a restricted range (no notes too high or too low); and Rhythms based strictly on the articulation of the word being sung (meaning no steady dancelike beats). Chant developed separately in several European centers, the most important being Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan and Ireland. Chant was developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating Mass. Each area developed its own chant and rules for celebration. In Spain and Portugal, Mozarabic chant was used, showing the influence of North Afgican music. The Mozarabic liturgy survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy. -

Download Download

Anonymous I and Prologus in tonarium: Changing Interpretations of Music Theory in Eleventh-Century Germany T. J. H. MCCARTHY Abbot Bern of Reichenau (d. 1048) stands as a formative influence upon eleventh- and twelfth-century German music theorists. Prologus in tonarium, the longer of his two music treatises, takes the form of a prologue in twelve chapters to an extensive tonary.1 His pairing of the theoretical prologue with the tonary—a list of chants classified according to mode—emphasizes the fundamental connexion between music theory and singing, which was the salient feature of the ars musica in the monastic and cathedral schools of Germany during the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Abbot Bern dedicated this treatise to Archbishop Pilgrim of Cologne, which implies a date of composition between 1021 and 1036.2 Prologus in tonarium exerted a considerable influence on subsequent generations of south-German music theorists, for it was widely copied during the eleventh and twelfth centuries: today Prologus survives in over thirty manuscripts while Tonarius survives in seventeen.3 The provenances and origins of the eleventh- and twelfth-century recensions show the treatise to have been widely disseminated in southern Germany. To this total must be added the evidence of library catalogues and known lost copies: the treatise was available in the monasteries of Muri, Reichenau, St Blasien, St Georgen, Tegernsee and Weissenau during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.4 1 The most recent edition of Bern’s musical works is Alexander Rausch (ed.), Die Musiktraktate des Abtes Bern von Reichenau. Edition und Interpretation, Musica mediaevalis Europae occidentalis, 5 (Tutzing: Schneider, 1999). -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Insular sources of thirteenth-century polyphony and the significance of Notre Dame. Losseff, Nicola The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 -1- INSULAR SOURCES OF THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF NOTRE DAME Nicola Losseff Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at King's College, London, 1993 1LoNDgt UNW. -

Guido of Arezzo and His Influence on Music Learning

Musical Offerings Volume 3 Number 1 Spring 2012 Article 4 2012 Guido of Arezzo and His Influence on Music Learning Anna J. Reisenweaver Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Practice Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Reisenweaver, Anna J. (2012) "Guido of Arezzo and His Influence on Music Learning," Musical Offerings: Vol. 3 : No. 1 , Article 4. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2012.3.1.4 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol3/iss1/4 Guido of Arezzo and His Influence on Music Learning Document Type Article Abstract Throughout the history of Western music, Guido of Arezzo stands out as one of the most influential theorists and pedagogues of the Middle Ages. His developments of the hexachord system, solmization syllables, and music notation revolutionized the teaching and learning of music during his time and laid the foundation for our modern system of music. While previous theorists were interested in the philosophical and mathematical nature of music, Guido’s desire to aid singers in the learning process was practical. -

The Spiritual Value of Singing the Liturgy for Hildegard of Bingen

THAT THEY MIGHT SING THE SONG OF THE LAMB: THE SPIRITUAL VALUE OF SINGING THE LITURGY FOR HILDEGARD OF BINGEN. A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada (c) Copyright by Miranda Lynn Clemens (Sister Maria Parousia) 2014 History M.A. Graduate Program September 2014 Abstract That They Might Sing the Song of the Lamb: The Spiritual Value of Singing the Liturgy for Hildegard of Bingen. Miranda Lynn Clemens (Sister Maria Parousia) This thesis examines Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179)'s theology of music, using as a starting place her letter to the Prelates of Mainz, which responds to an interdict prohibiting Hildegard's monastery from singing the liturgy. Using the twelfth-century context of female monasticism, liturgy, music theory and ideas about body and soul, the thesis argues that Hildegard considered the sung liturgy essential to monastic formation. Music provided instruction not only by informing the intellect but also by moving the affections to embrace a spiritual good. The experience of beauty as an educational tool reflected the doctrine of the Incarnation. Liturgical music helped nuns because it reminded them their final goal was heaven, helped them overcome sin and facilitated participation in the angelic choirs. Ultimately losing the ability to sing the liturgy was not a minor inconvenience, but the loss of a significant spiritual and educational tool fundamental to achieving union with God. Key words: Hildegard of Bingen, Letter to the Prelates of Mainz, monasticism, liturgy, music medieval music theory, medieval aesthetics, body and soul, education. -

Dist Vol 2 No1 Frnt.Pub

Artwork by ugne janonyte Distinctions: an honors student journal Volume 2, no. 1 fall 2006 Distinctions: An Honors Student Journal Kingsborough Community College The City University of New York Volume 2, No. 1 Fall 2006 Distinctions: An Honors Student Journal Faculty Mentor and Editor: Dr. Barbara Walters, Behavioral Sciences & Human Services Co‐Editor: Aline Bernstein Co‐Editor Liane Naber Student Advisory Committee: Aline Bernstein Liane Naber Faculty Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Walters, (Committee Chair) Dr. Eric Willner, Director, Honors Option Program Professor Norman Adise, Business Administration Professor Rick Armstrong, English Professor Cindy Greenberg, Speech and Communications Professor Judith Wilde, Art Administrative Liaison: Dr. Reza Fakhari, Associate Dean of Academic Affairs The artwork on the cover is by Graphic Design student Ugne Janonyte. Copyright @2006 Kingsborough Community College LETTER FROM THE EDITOR We are very pleased and proud to present the Fall 2006 issue of Distinctions as we enter our second year of producing a journal for honors students at Kingsborough Commu‐ nity College. This issue reflects the diversity of our students, not just in terms of ethnicity, age, gender, and religion, but also in terms of intellectual interests and as stakeholders in the community and world in which they live. The range of papers in Volume 2, No. 1, of Distinctions is truly extraordinary and we as an academic community can only sit back in awe as our students reveal through their writing the complexity of the world in which they live. This journal is our collective effort to provide a forum for nonfiction writing and could not be produced without the support of the entire community. -

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76574-9 - Medieval Song in Romance Languages John Haines Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76574-9 - Medieval Song in Romance Languages John Haines Index More information Index Abelard, Peter, 132 on Mary, 136–7 ‘Abril issia’, 77 on pagan goddess cults, 133–4 Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 96 on whether Christ danced, 142 Acts of Th omas, 124 Augustus, 122 Adam de la Halle, 93, 144–8, 151–2, 153, Aurelian of Réôme, 151 154–5 Adonis, cult of, 123, 124, 127, 130 Bacchus, cult of, 122 Aeneid, 34 Banniard, Michel, 15n29 Agnes, Sponsus and Play of Saint, 37 Barcelona, 83 Ailred of Rievaulx, 43, 44, 46, 49, 155, 169 Bartsch, Karl, 53 Albert the Great, 158 Bec, Pierre, 52 Alexandre-Bidon, Danièle, 40 Beck, Jean, 96 Alexandria, 123 Bede, the Venerable, 18, 22, 92n46 Amalar of Metz, 151 Bédier, Joseph, 87, 89, 100–1 Ambroise, 99 Beleth, John, 59 Ambrose, Saint, bishop of Milan, 125, 134, 135 Beneventan script, 36 Ambrose Autpert, 62, 135 Benko, Stephen, 133, 134, 136 Amiens, 105 Berger, Anna Maria Busse, 148, 151 Andria, 25, 78 Berkvam, Doris Desclais, 158 Anglo-Norman song, 31 Berlin, 53 Anglo-Saxon song, 18 Bernard de Clairvaux, 48, 49, 132, 135, Annales archéologiques, 153 168–9 Ansileubus, 25–6, 32, 33 Bernard Silvestris, 118 archaeology, 153 Bernart de Ventadorn, 49, 52, 53, 78 Aristotle, 118, 158 Bernart Marti, 52 Arles, 63 Berschin, Helmut, 129 Arminius, 90 Berschin, Walter, 129 Arnaut Daniel, 76 Bertran de Born, 81 Arras, 146 biblical references Ars cantus mensurabilis, 11 Acts of the Apostles, 132 Ars Nova, 149 Apocalypse, 135 Artemis, 133 Ezekiel, 46, 65 Arthurian legend, 99–100, -

Veritatis Splendor #120

OUR FOREFATHERS IN THE MONASTIC LIFE Biographies of Great Monastic Saints by Pope Benedict XVI Selections from the Wednesday Audiences June 20, 2007 – October 6, 2010 - 1 - - 2 - Table of Contents Athanasius of Alexandria . 5 Basil . 11 Gregory Nazianzus . 21 Gregory of Nyssa . 31 Eusebius of Vercelli . 42 Jerome . 48 Aphraates “the Sage” . 61 Boethius and Cassiodorus . 66 Benedict of Norcia . 74 Romanus the Melodist . 81 Gregory the Great . 88 Columban . 102 Maximus the Confessor . 108 John Climacus . 115 Bede the Venerable. 123 Boniface. 130 Ambrose Autpert. 138 John Damascene. 146 Theodore the Studite. 152 Rabanus Maurus. 159 Cyril and Methodius. 165 Odo of Cluny. 171 Peter Damien. 178 - 3 - Symeon the New Theologian. 184 Anselm. 190 Peter the Venerable. 196 Bernard of Clairvaux. 202 Monastic Theology and Scholastic Theology 209 Bernard of Clairvaux and Peter Abelard . 215 The Cluniac Reform . 220 Hugh and Richard of Saint-Victor . 225 William of Saint-Thierry . 232 Rupert of Deutz . 238 Hildegard of Bingen . 245 Matilda of Hackeborn . 266 Gertrude the Great . 273 - 4 - Saint Athanasius of Alexandria Dear Brothers and Sisters, Continuing our revisitation of the great Teachers of the ancient Church, let us focus our attention today on St. Athanasius of Alexandria. Only a few years after his death, this authentic protago- nist of the Christian tradition was already hailed as "the pillar of the Church" by Gregory of Nazianzus, the great theologian and Bishop of Constantinople (Orationes, 21, 26), and he has always been considered a model of or- thodoxy in both East and West. As a result, it was not by chance that Gian Lorenzo Ber- nini placed his statue among those of the four holy Doc- tors of the Eastern and Western Churches — together with the images of Ambrose, John Chrysostom and Au- gustine — which surround the Chair of St. -

Contemporary Understanding of Gregorian Chant – Conceptualisation and Practice

Contemporary understanding of Gregorian chant – conceptualisation and practice Volume two of three: Appendices I Eerik Joks Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of York Department of Music November 2009 384 List of contents Appendix 1 Interview with Michiko Hirayama in Rome, on 8.‐9.03.2006. 389 Appendix 2 Interview with Professor Godehard Joppich in Frankfurt, on 1.03.2005. 395 Appendix 3 Figure 1 (additional). Different possibilities of reception of MSLM. 405 Appendix 4 Intervjuu Arvo ja Nora Pärdiga 2005. aasta suvel. 406 Appendix 5 Interview with Professor Godehard Joppich in Frankfurt, on 20.12.2008. 415 Appendix 6 Questionnaire for Performers and Experts of Gregorian chant in English. 420 Appendix 7 Questionnaire for Performers and Experts of Gregorian chant in Estonian. 433 Appendix 8 The printed version of the Questionnaire for Performers and Experts of Gregorian chant in English (A5) (in the pocket on the back cover). 445 Appendix 9 Tables 92‐203 (TAO). Raw data of the results of questionnaire in the form of frequency tables. 446 Appendix 10 Correspondence to respondents concerning the Questionnaire. 489 Appendix 11 Table 25 (additional). Number of responses, mean values, and variance of the answers to the questions 1‐27 ‘Gregorian chant for me means [an argument]’; sorted by mean; AMP=4.3. 494 Appendix 12 Table 26 (additional). Number of responses, mean values, and variance of the answers to the questions 1‐27 ‘Gregorian chant for me is [an argument]’; sorted by variance; AMP=3.4. 495 Appendix 13 Table 27 (additional). Number of responses, mean values, variance, ratio of mean and variance, subtraction of mean and variance, position of the arguments in the table of the answers to the questions 1‐27 ‘Gregorian chant for me means [an argument]’; sorted by the subtraction of mean and variance (‘M‐V’).